Key Takeaways

- A visualization group facing a changing need for its services reinvented itself as a multimedia lab to serve a wider audience with a growing demand for digital content.

- The new media lab soon became a nexus for exchanging teaching ideas and a place where instructors could find support and guidance from outside their disciplines, making collaborative engagement the lab's most important "product."

- Because staff spend more time communicating between campus silos than perhaps anyone else, the potential to spark collaborative fires is huge — and so is the payoff for the campus community.

In a scene reminiscent of The Graduate, the director of my workgroup summoned me to his office, closed the door, and said, "Dave, I have one word for you: multimedia." As I calculated the number of steps to the exit, he continued, "You can't draft salamander skulls forever. They're running out of species."

It was 2003, and I was a graphic designer and illustrator at a major research university. Things were changing in my little visualization department. We'd dropped from three designers to two, and the arrival of desktop publishing was making deeper and deeper inroads into our business. Faculty were increasingly using programs like Illustrator and PowerPoint to produce their own figures, and I hadn't actually knocked out a decent line drawing of a salamander skull in almost a year.

My director had some money to play with and a wild idea. Multimedia was all the buzz, and he figured our office would be the perfect place to house a small lab in which faculty and students could "make movies and other cool stuff."

It was exactly seven steps to the door, but I was worried about the major dogleg around the end of his desk.

He went on to share his vision with me. He saw teams of energized students collaborating on cutting-edge documentaries and immersive animations. I saw kids with backwards baseball hats spilling Mountain Dew on expensive equipment. I was a designer, not a custodian, and I was mortified.

Three weeks later I was unpacking computers, cameras, and tripods, and a week after that, my office was the Media Lab. In retrospect, the change in my job duties was the best thing to happen to my career.

A Lot Like the Dentist's Office

Initially, my fears proved well founded. A lot of chaos occurred in our lab during its first semester. Several writing faculty had included short video assignments in their syllabi, and their students typically came to us in a funk. "I'm in a writing class; why do I have to make a movie?"

We weren't sure we knew. Sure, the inclusion of nontextual modes in a class devoted to persuasive communication made sense on paper. But these students had somewhat hazy goals and even hazier guides — us.

We were surprised that these digital natives, accustomed as they were to computing and the Internet and the mastery of every conceivable digital gizmo, had so little appetite for learning to use even the simplest of video-editing applications. Also, the equipment was glitchy, and by the time the postage-stamp-sized movie files had been rendered, they were pixilated and jumpy. Clearly, this fell short of the rich multimedia experience our director had in mind.

So an idea came to us: why not pay a preemptive visit to the classroom and demonstrate the proper use of the technologies involved in these assignments? Teaching and troubleshooting on an as-needed basis was frustrating, and, worse, couldn't be scaled. What if we went into the classroom and showed all the students how our pool of video cameras worked or how to safely mount and eject a remote hard drive? What if they learned the basics of nonlinear video editing before they came to our lab and ruined our expensive equipment?

This minor tweak in our mode of support represented a major tweak in lab strategy, and it paid off handsomely. Students showed up ready to work and required much less one-on-one assistance. Additionally, by making in-class appearances, we were no longer just "the lab guys" but partners. Our little lab was, by extension, a much happier and more productive place.

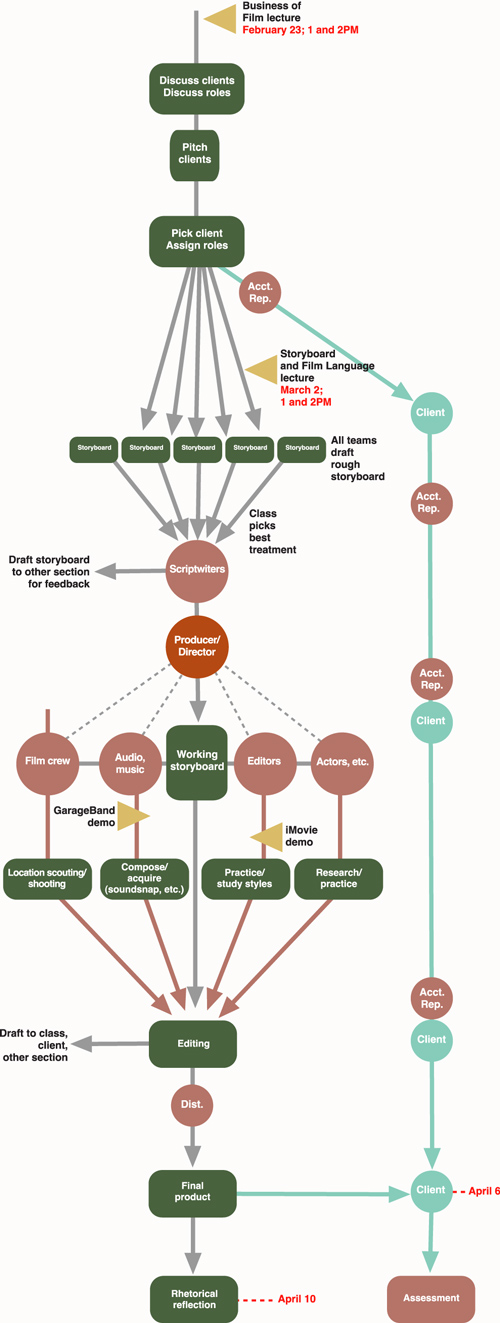

We became partners with faculty as well. Because working with digital video and audio files is considerably more complex than writing a paper or giving a presentation in class, our roles evolved to include consultative support, and we were able to alert instructors to minefields that lurked along the multimedia trail. We encouraged them to keep the assignments short and to expect coarse production values. We also helped them plot the waypoints and production windows within which their classes would operate. We knew that tracking and managing a media project could make an instructor feel more like a project manager than a teacher, and as much as possible we offloaded the low-level hassles that come bundled with large groups of students using unfamiliar technologies. Figure 1 shows a flowchart mapping out the formation of student teams, the timing of our guest lectures and demos, and the placement of production waypoints for a large-scale student project. I have found that graphically portraying the development and workflow of student projects over time helps us, our faculty, and students stay current and focused on project needs and goals.

Figure 1. Sample Multimedia Production Process and Schedule

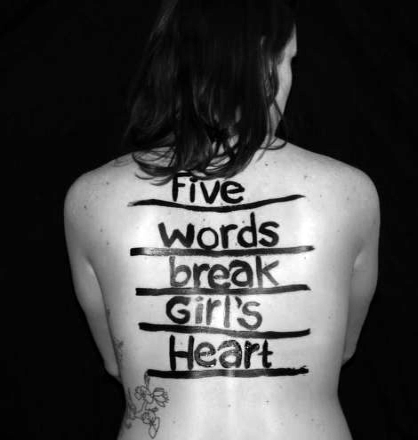

Though dismayed by the quality of work done by some of our student guests, as creative professionals we also appreciated good work when we saw it. In spite of — or because of — their use of entry-level software and consumer-grade hardware, the students hit the occasional home run (see Figure 2, one student's achingly poignant reflection on the deaths of five of her young friends). Although loosely mandated to keep our distance, we couldn't help but take a degree of personal pride in the final result. Suddenly, it seemed, we were feeling a bit less like custodians.

Figure 2. "Five Words Break Girl's Heart" by Tierney Lyn Cochran

© 2011 Tierney Lyn Cochran. Used with permission.

Glitz Without Substance

Of course, we saw some astonishing failures, as "Chad" will now demonstrate.

It's 11:25 a.m. Friday and the video essay assignment for English 2300 is due at noon. The students have been asked to put together a short piece reflecting on a chapter from Norman Mailer's The Armies of the Night.

A relaxed Chad strolls into the lab and informs us that he's ready to start work on the project.

"Start? But it's due at noon. Your classmates have been working on this for three weeks. You're just now starting?"

"No worries," says Chad, as he implants an ear bud and fiddles with his iPod. "I only need about 20 minutes."

He's done in 15.

Curious, we follow him to class. We've come to believe that attending student presentations helps us do a better job in the lab, and this is one presentation we don't want to miss.

After his classmates have presented several murky but interesting videos, it's Chad's turn. He saunters to the front of the class and hits "Play" on the DVD deck. The room is enveloped in a thunderous stew of 60s rock music and jerkily edited black-and-white photos that riffle across the screen like shuffled cards.

When it's over and the screen has faded to black, his classmates go berserk and the instructor breaks into wild applause. In the back of the classroom, we mutter, "But it only took him 15 minutes!"

In following semesters, when we've met with faculty to map out lab support for their classes, Chad's piece invariably comes up.

"You might want to look out for the kids who do big, noisy, seductive pieces but don't actually develop a compelling argument," we tell them. "We see this every semester, and we know firsthand that they put almost no time or thought into their projects. What they turn in is a slideshow with a killer soundtrack."

"Thanks. Any idea what I should look for?"

A Crossroads of Ideas

We keep an archive of outstanding student projects, which we're happy to share. When teachers initially latch on to the idea of incorporating a multimedia assignment in their coursework, they're at a loss as to how the project should look. How long should the video be? Should students work in teams or individually? Can they use "found" material, or should their work be original? Our "library" of past student creations gives them a start in planning their assignments and has improved the quality of their students' work.

It doesn't end with the assignment. How do you objectively grade something as subjective as a video reflection on a spiritual event in someone's past? You don't have to go it alone. Using our lab as a hub, our faculty partners have designed and co-evolved various rubrics for project assessment. While not every instructor agrees on how the perfect student video will look in its final screening, the rough outline of a grading matrix, shared and fine-tuned by the teachers we've worked with in past semesters, provides an excellent start on assessment.

Our lab has comfortably grown into a "crossroads of ideas," which has led us to become more deeply involved in content. What better place than the media lab to store and disseminate best practices for assigning, managing, and grading media projects, especially between disciplines?

A standard service we now provide includes hosting roundtables on teaching with multimedia. Having faculty gather for a few hours per academic year is proving to be a wonderful opportunity for fostering all manner of collaborative thinking, not only in how multimedia assignments might best be framed, managed, and graded, but in other aspects of teaching as well. In fall 2010, for example, roundtable participants, in discussing several student service-learning media production projects, moved into the deeper subject of civic engagement and how the campus could better work to marry student media projects with the communications needs of nonprofits in the community.

The media lab is unparalleled as a nexus for exchanging teaching ideas and styles and as a "place" where instructors can look for support and guidance from outside their disciplines. We've come to see collaborative engagement as our most important "product."

Not surprisingly, the watering-hole phenomenon extends to students and others. We find ourselves in serendipitous, matchmaking situations. John, for example, is an ace graffiti artist with a very interesting background in "guerilla marketing" who's unsure of the real-world applicability of his talents or how to adequately describe his skills. Mary has been assigned to the campus-wide promotion of a student volunteer group for her 3000-level writing class. She's a very good writer but hasn't a clue about edgy design and street art. John, meet Mary.

Click on an Expert

Early on in our work with campus instructors we noticed that students who had meticulously planned their projects produced much better work, and they finished their assignments sooner. What was needed, it seemed, was additional instruction in planning, so in the summer of 2005 we put together a 40-minute lecture on film language and storyboarding. Using clips from Hollywood classics, we showed that the same techniques that Orson Welles and Martin Scorsese used to rivet audiences to the screen are available to beginners using consumer-grade cameras and programs such as iMovie and GarageBand.

The lecture, and the storyboard exercise that accompanies it, helps budding videographers graphically organize their thoughts and media assets. It is now a standard component of the suite of classroom services we offer campus instructors.

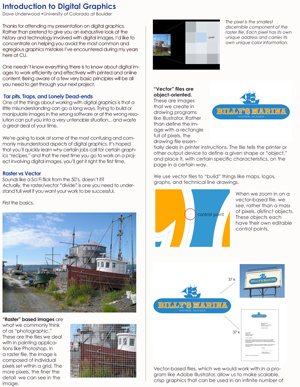

The storyboard lecture is a true workhorse and has served as a natural springboard into exploring other topics. Students working on a service-learning print campaign might, for instance, benefit from our presentation on dealing with picky clients. And students assembling digital portfolios find themselves in perennial need of deeper instruction on appropriate image resolution and file types for delivery-specific needs. Figure 3, from our talk on digital graphics, shows students why knowing the difference between working in raster and vector-based environments is critical to executing successful design. We also put students through a deconstruction exercise. Students are shown a 30-second commercial, then asked to storyboard significant scenes captured from the piece. This exercise gets students aware of the elements that can be efficiently managed and orchestrated in authoring an effective storyboard.

Figure 3. Handout on Digital Graphics

Our current series of guest lectures now includes talks on graphic design, typography, effective campaigning, podcasting, designing in PowerPoint, and more. In 2006 we gave the storyboard talk six times to something like 80 baffled students and delivered two in-class demos of digital video software. This year's spring semester found us giving over 55 lectures to nearly 900 students, and the demand for class visits continues to grow.

Lecturing on any given subject is not always enough. A certain degree of downstream coaching, handholding, and even small-group technical instruction is often required for students to make that long leap from the theoretical to the practical. And so, in recent semesters, we've added a sort of "office hours" element and made a regular practice of helping students bring their media creation ideas to fruition. This assistance might be as simple as directing student teams toward great resources for design inspiration, or as exacting as, for instance, showing a student how Photoshop can be used to achieve a desired look and feel for a DVD menu.

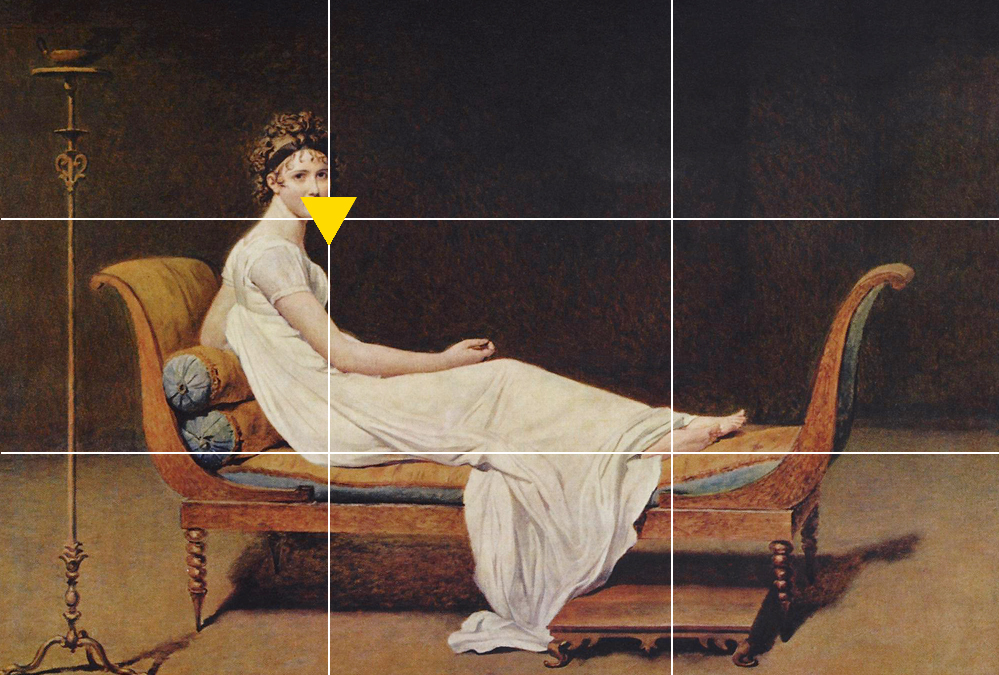

It's especially gratifying, after mentoring student creators, to see certain aesthetic and visually powerful ideas show up in their work. After stressing the importance of dynamic framing or of using the "Rule of Thirds" in composing a scene for a video, we are heartened to see the results in classroom presentations. Figure 4, a screen capture from a student-produced video promoting a local therapeutic riding center, shows how an illustrated example (Figure 5) from the storyboard lecture affected a final shot, with the videographer using the Rule of Thirds in framing the speaker's face. Figure 6 shows a still image from a student-produced video in which attention to framing was used to make an otherwise serviceable shot great.

Figure 4. The Rule of Thirds Used for Balance and Dynamics

Figure 5. Portrait of Madame Récamier, by Jacques-Louis David (1800)

Figure 6. Still from a Student Video

© 2011 Therapeutic Riding Center. Used with permission.

Getting to Know the Neighbors

Building on this notion of lab-as-a-hub-of-expertise, we've also recently begun enlisting media and communications experts from within the community to work with our classes. Copyrighters, cinematographers, designers, and other creative professionals are surprisingly amenable to giving guest lectures to university students, as well as to providing some degree of coaching and feedback on projects. Reaching out to creative professionals from the private sector to come and share their tales from the trenches has been very well received, if for no other reason than the elevated sense of legitimacy students consequently attach to their own projects. Our lab is as well situated as any department on campus to build bridges to the professional community, and our longstanding relationship with local vendors and service providers has served as a conduit into a deep pool of readily available speakers.

Mopping Up

With university budgets nationwide under pressure, and with administrators looking for greater efficiencies in how staff support the institution's mission, adopting a proactive stance when defining how we serve our customers is a win-win approach. Because we, as staff, spend more time darting between campus silos than perhaps anyone else, the potential for us to spark collaborative fires is huge — and so is the payoff for the campus community.

The changes in mission of our media lab have made it a vital contributor to the institution's teaching mission. I'm hoping that those of you who work with — Oops, gotta' run: I think I see Mountain Dew running out from under the door of Edit Bay Number Two!

© 2011 David M. Underwood. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.