Key Takeaways

- Higher education historically has focused on instructors teaching rather than students learning, an ineffective approach that could seriously hamper the promise of mobile learning.

- Successful student learning emerges from active engagement, connection to the students' prior knowledge, and simulation of real world experiences — all facilitated by engaging learners' senses through multimedia.

- Higher education should stop thinking about these powerful mobile multimedia devices as only consumption devices — to live up to the promise of mobile learning, students should use them as production devices.

In both the 2010 Horizon Report1 and the 2009 annual ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology,2 which has a whole chapter focused on mobile devices, the vast majority of examples about how students and faculty were using mobile devices in their classes discussed alternative modes of content delivery. Examples included things like using laptops and e-readers to deliver textbook material and using iPods and cell phones for other multimedia materials (audio and video). Faculty and students glorified the ability to "learn" on the bus, in line at the grocery store, and at the beach. However, all of these examples represent students consuming knowledge in alternate environments.

I'd argue that content delivery isn't even half the picture of teaching and learning. Plus, higher education has been doing mobile content delivery, or mobile teaching, for hundreds of years. Individuals have had access to "portable learning devices" since the advent of the printing press; we call them books. During both undergraduate and graduate school, I always carried around a copy of whatever I needed to read in case I got stuck waiting somewhere like the doctor's office or the post office.

Anyone reading this issue of EDUCAUSE Quarterly probably already buys into the idea that mobile learning is the next big thing. I definitely do! I'll never forget the day during the fall 2008 semester when one of my students walked into class and confessed, "I had to take the quiz at work."

My face scrunched up. "On the computer at work?"

"My phone," he said as he reached into his pocket and pulled out his phone.

My eyes bulged. "You took the quiz, in WebCT, on your phone?"

A pause as we both looked at his small phone screen.

"That wasn't pleasant, was it?"

"Not really."

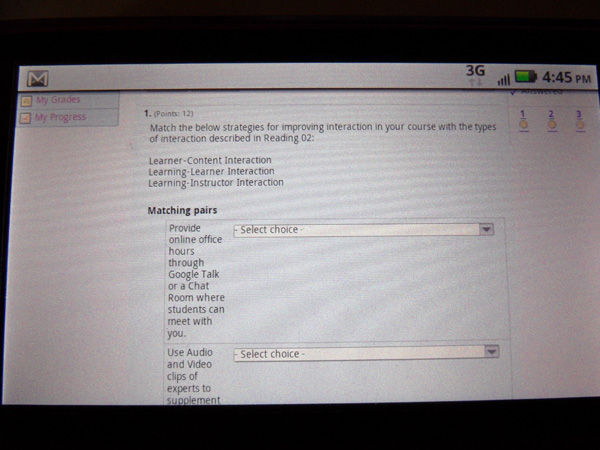

Figure 1 shows a WebCT quiz on my DroidX phone, with its ability to zoom in (which my student's phone did not have). Really not pleasant.

Figure 1. A WebCT Quiz on a DroidX Phone

To me this exchange is representative of the current problem with most discussions about mobile learning. What continues to surprise me in all the excitement about mobile learning is that so few people really talk about mobile learning instead of mobile teaching.

I really shouldn't be surprised. Historically, higher education has had the problem of focusing on instructors teaching instead of students learning. Since the publication of Robert Barr and John Tagg's article in Change3 in the mid-1990s, research has shifted away from how instructors teach to how students learn. Research now shows that successful learning needs to be active and engaging, connect to the students' prior knowledge, and simulate real-world experiences. The promise of mobile learning is the ability to engage students with creative and/or sophisticated content learning activities on their multimedia production devices. This is worth repeating: To achieve the promise of mobile learning, we have to stop thinking about these powerful mobile multimedia devices as only consumption devices and get students using them as production devices.

Multimedia = Engaging Multiple Senses

OK, OK, I'll support the proponents of mobile teaching who argue that content delivery on multimedia mobile devices not only makes the content more accessible, it also helps students engage the content using multiple senses. Brain researchers have been telling educators for quite a while that engaging multiple senses helps students better learn material. Therefore, the excitement here is not so much about the portability or mobility of these teaching devices; instead, it is that these devices can both convey teaching material in more than two media (text and images) and be portable.

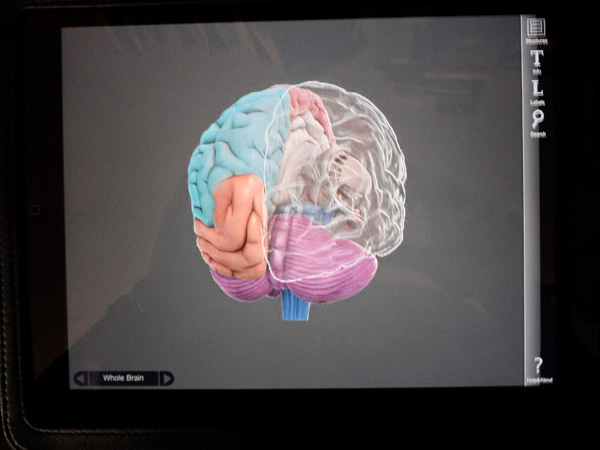

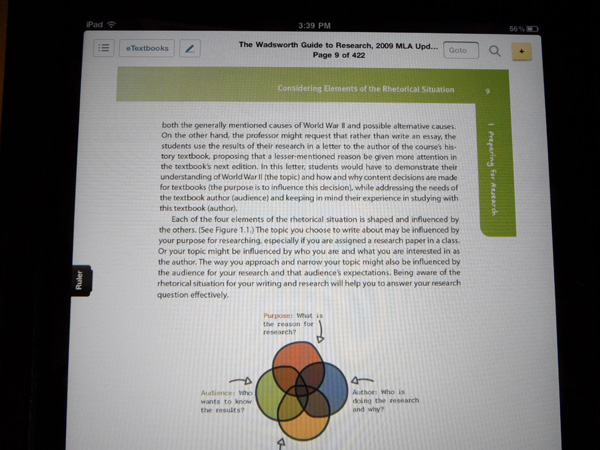

To make these alternative content delivery, or teaching, devices really live up to the hype of multimedia materials, we need to move beyond the heavy reliance on text. For every robust multimedia, mobile-content delivery example I see — things like a multimedia periodic table or a three-dimensional brain (see Figure 2, a 3D brain app on the iPad4) — I learn about three or four examples of static copies of textbook pages, or "Look! I made my [text-heavy] WordPress blog posting accessible on a mobile device!" In other words, we've still got a lot of digital books floating around, being hailed as amazing advancements in teaching and learning. Although I know the majority of materials currently available to students on their portable multimedia consumption devices are still primarily text-based, maybe including a static image or two (see Figure 3, a color, static digital page with a Venn diagram that is no different from the same page in the printed book5), I am looking forward to the robust multimedia resources that we should see emerging over the next few years.

Figure 2. 3D Brain App on the iPad

Courtesy of Dolan DNA Learning Center

Figure 3. Static Digital Page Identical to Print Book

Heinle/Arts & Sciences, a part of Cengage Learning, Inc. Reproduced by permission.

Mobile Learning = Active Learning

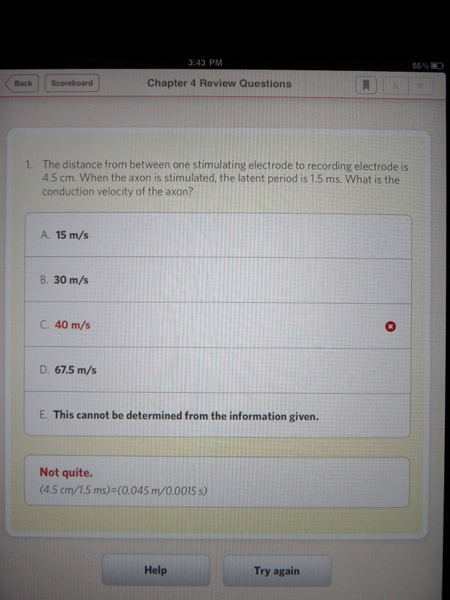

Truly multimedia textbooks that include soundtracks, animations, and videos do not live up to the promise of mobile learning. We need to explicitly develop learning materials and activities that go beyond simple content delivery, or just teaching. In other words, it's not enough for CourseSmart to make PDF-like copies of textbooks available for students to purchase; instead, we need the type of interactivity we're starting to see from the textbooks available in Inkling. (Figure 4 shows a chapter quiz that students can use to self-test their knowledge.) The 2011 Horizon Report makes the bold claim "What makes electronic books a potentially transformative technology is the new kinds of reading experiences that they make possible."6 That "potentially" still looms pretty large, doesn't it?

Figure 4. Inkling Chapter Quiz

To move beyond mobile teaching — to be transformative — we need to think more systematically about how to design education to facilitate learning. One simplistic way to break down instructional design is for instructors to align their learning objectives over:

- Content delivery

- Content learning

- Learning assessment

Most of the examples I've been seeing, hearing, and reading about in terms of mobile learning only apply to one-third of the steps needed for students to learn, and prove they've learned, the course material. In other words, it is not enough to just give students PDFs of pages from an anatomy textbook. It's not even enough to allow them to take self-grading quizzes. We need to provide materials or applications that allow students to practice identifying parts of the body on their mobile multimedia devices before taking the high-stakes midterm or final exam.

Mobile Learning = World as Classroom

The majority of students already use their mobile devices to interact with and learn from the world around them. They engage their current situation with texts, tweets, and Facebook updates to their friends. They Yelp out for help finding a place to eat dinner and report back their findings. Some even use Google Goggles to find information about their surroundings from a picture. And they already do this in our classrooms, if we let them.

"See this part of your presentation? You could add another image here and…"

"Wait, let me take notes on this."

My student whips out her phone and flips up the screen to access the keyboard.

Shifting her eyes back up to mine, "What were you saying?"

We go on talking in my office for another 10 minutes with her typing away on her phone (Figure 5). As she gets up to leave, Jazmyn says, "I wish all my instructors let me use my phone. It's a lot easier to get these to my computer than stuff on a piece of paper."

Figure 5. Jazmyn Typing on Her Phone in My Office

With the majority of students in higher education owning mobile devices that allow them to record text or audio, and a growing number also able to record both static images and dynamic videos, why aren't more of us developing activities for content learning and learning assessment? At minimum we could be asking our students to capture raw material from the real world and engage with it based on the concepts we are teaching them.

It's one thing to learn about different architectural styles in a Western Civ or Construction textbook or lecture; it's another to apply what you've learned by going out into the community and taking pictures of buildings and then identifying the architectural influences. It's one thing to hear or read about the results of sociology studies about gender bias; it's another to go out, collect primary data, and immediately show, as well as discuss, the dynamically growing study results with the recently queried participant. In both cases the activity of capturing "raw" digital material can lead to further learning or assessment activities where students might develop multimedia projects.

Go Mobile!

"But Shelley, I teach at a college with a majority <insert name of disadvantaged population here> student population and they do not all have access to these technologies!"

"Wow," I say. "You accept handwritten end-of-semester papers in your course?"

"Well, no…" pausing because I seem to have gone slightly off track with my response.

Then, "But, students have access to computers and printers in the library — we're talking about expensive mobile devices here."

"And you don't think your students could be just as resourceful finding a mobile multimedia production device as they are at finding regular access to a computer and the Internet?"

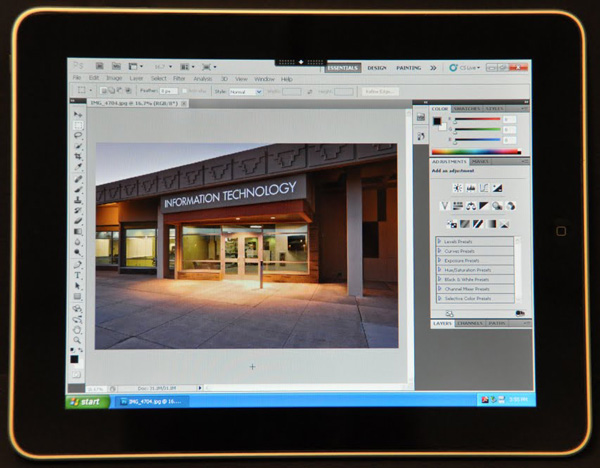

Can you tell I've had this conversation before? I'm not saying the digital divide isn't real, but I firmly believe access is not an excuse. Just as instructors will need to be creative in developing and assessing these mobile learning activities, instructors and institutions will need to help students be creative in finding access to different mobile multimedia production devices. For example, most schools can't afford campus-wide licensing of various Adobe digital production suites. However, having a smaller number of licensed versions shared on a Citrix server with the ability for students to check out laptops and iPads with Citrix running on them gives faculty outside of the art and business departments the ability to require students to manipulate images. For example, Scottsdale Community College in Arizona has a Citrix environment that allows students to access applications like Photoshop on an iPad (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Shared Citrix Environment for Photoshop

One of the easiest ways for individual instructors to address the access and support issues is to have students work in groups, share access to resources, and help one another figure out how to do it all. Bonus point: Employers want students who know how to work in groups. Getting students engaged in mobile learning projects might not only better facilitate learning, it might also have them learning about various 21st century literacies like group work, composing in multiple environments, and information literacy.

I started this piece referencing how the 2010 Horizon Report and the results of the 2009 annual ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology disappointed me with their lack of vision for the promise of mobile learning. I am happy to say that others also worried about the focus on mobile teaching. The section on mobiles in the 2011 Horizon Report emphasized students' interactivity with the material on their mobile devices, for example. And although the results of the 2010 annual ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology7 focused more on cloud computing, it reports a growing number of students with Internet-capable mobile devices access the Internet daily, especially for social networking activities that imply social interaction and sharing of resources. This gives me hope — hope that students will demand more interactive mobile learning activities from us, and hope that we will meet that challenge creatively.

- Larry Johnson, Alan Levine, Rachel Smith, and Sonja Stone, "The Horizon Report 2010 Edition," New Media Consortium (2010).

- Shannon D. Smith, Gail Salaway, and Judith B. Caruso, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2009 (ECAR Research Study, vol. 6, 2009), (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2009).

- Robert B. Barr and John Tagg, "From Teaching to Learning — A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education," Change (November/December 1995).

- Produced by the Dolan DNA Learning Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- Susan K. Miller-Cochran and Rochelle L. Rodrigo, Wadsworth Guide to Research, Documentation Update Edition (Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009), 1E. (2011).

- Larry Johnson, Rachel Smith, Holly Willis, Alan Levine, and Keene Haywood, "The Horizon Report: 2011 Edition," New Media Consortium (2011), p. 8.

- Shannon D. Smith and Judith Borreson Caruso, with an introduction by Joshua Kim, The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010 (ECAR Research Study, vol. 6, 2010), (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2010).

© 2011 Rochelle L. Rodrigo. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.