Key Takeaways

- The U-Pace instructional approach combines self-paced, mastery-based learning with instructor-initiated Amplified Assistance in an online learning environment.

- Extensive evaluation showed that, compared to conventional instruction approaches, U-Pace instruction facilitated greater learning and greater academic success for all students in Introduction to Psychology courses.

- In terms of resources, U-Pace requires only a learning management system (such as Blackboard, Desire2Learn, or Moodle).

- U-Pace can be applied in any course or discipline, and resources to help instructors adopt the U-Pace approach are freely available.

Because the transition to a knowledge-based economy requires an educated workforce, colleges and universities have made retention of students — particularly those who are academically underprepared — an institutional priority. College completion leads to economic and social advancement for students and is also critical to the nation's economic and social strength. To increase student success, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee (UWM) implemented the technology-enabled U-Pace instructional approach in Introduction to Psychology, a course that most students take during their college career. U-Pace combines self-paced, mastery-based learning with instructor-initiated Amplified Assistance in an online learning environment.

U-Pace Instruction

There are two components to U-Pace instruction: mastery-based learning and Amplified Assistance. The mastery-based learning component allows students to progress to new content only after they have mastered the concepts in a module (equivalent to half a chapter), as evidenced by achieving at least a 90 percent on a corresponding multiple-choice quiz. Students have six minutes to complete each 10-question quiz. This time limit, based on empirical testing, has been validated with quiz times from more than 2,000 students. Students receive an immediate quiz score, but are not told what questions they got wrong; the goal is for them to master the critical concepts in the module rather than learn the answers to specific questions.

We developed the quiz questions using Bloom's Revised Taxonomy1 as a framework to ensure that the majority of questions assess understanding beyond rote memorization. To earn at least 90 percent on each quiz, students must be fluent with the concepts and have a deep understanding of the material. As in most mastery-based learning approaches, students can retake quizzes an unlimited number of times without penalty, but must wait at least an hour (to study the material further) before attempting a retake. Retakes consist of 10 randomly selected questions; in each of the 24 quiz banks, there are about 80 questions. Figure 1 shows a sample quiz.

The learning management system (LMS) records information for each student, including quiz scores, number of quiz attempts, and time elapsed since last quiz attempt. Instructors can use this information to determine when to give Amplified Assistance (conveyed through e-mail), as well as what type of assistance is needed. Without using an analytics tool, author Diane Reddy has facilitated the success of up to 60 U-Pace students (without teaching-assistant support) in the same amount of time as required for a conventional course.

Amplified Assistance is accomplished most often by tailoring e-mail message templates found in the U-Pace Instructional Manual. These templates powerfully communicate to students that they can succeed, even if they are unsuccessful at the moment. As shown in the example below, Amplified Assistance messages provide students both timely, tailored feedback on concepts they have not yet mastered and constructive support and encouragement. The message below was sent to John, a student who had consistently worked on the course, but had stopped after he did not achieve a 90 percent after four attempts on quiz 3. The LMS record suggested that John might be giving up on quiz 3. By using a template in the U-Pace Instructional Manual and examining the questions John got wrong, the instructor was able to create this Amplified Assistance message to help John:

Hi John,

I know you are capable — you earned As on quizzes 1–2. I also believe you are a student who is motivated or you wouldn't have attempted the quizzes multiple times. Show me, and most importantly yourself, what you can do when you decide to do it. Believe you can do it. When you believe you can, your behavior will follow and you will do it. I will be checking your progress on Monday night.

Here are some concepts to go over:

- How is a message transmitted across a synapse?

- Focus on the difference between aphasia and apraxia.

- Learning the functions of the different brain structures is a very important part of this quiz. You might try the online review activities to help you practice with them.

GOOD LUCK!!! I can't wait to see you pass this quiz :-)

Your Instructor,

After receiving this Amplified Assistance, John took two more attempts to successfully complete quiz 3 and continued to work consistently on the course.

Amplified Assistance supports and encourages students, reinforces their persistence, and lets them know the instructor is with them each step of the way. It also helps students figure out why they are falling short of 90 percent mastery and what they can do to turn the situation around. In conventionally taught courses, Amplified Assistance with learning is offered periodically to the few students who request help, but in U-Pace instruction, Amplified Assistance is provided to all students at least weekly, and as often as needed. As a consequence of receiving this instructor-initiated Amplified Assistance, students perceive that the instructor has a strong belief in their ability to succeed. Although all students receive Amplified Assistance, the U-Pace instructor proactively intervenes — without students having to ask for help — whenever it appears students are struggling with concepts or giving up.

Instructors adapt templates found in the U-Pace Instructional Manual to praise both student accomplishments (completing a quiz by earning at least 90 percent) and, just as importantly, their efforts toward mastery (quiz attempts). The focus is on shaping students' behavior to achieve academic success and increasing students' perception of control over their learning. As students' perception of this control deepens, they attend more to coursework, laying the foundation for greater learning. This deepening sense of control allows students to persist in the face of academic challenges.

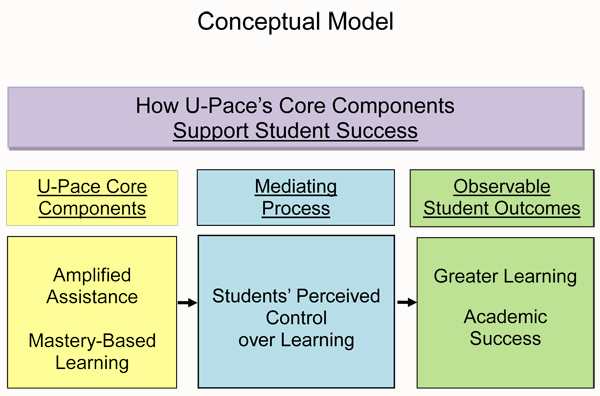

U-Pace's two components, Amplified Assistance with learning and mastery-based learning, work in concert. Amplified Assistance directly supports students' efforts to achieve mastery and progress in the course by providing instructor-initiated feedback on concepts not yet mastered, and the critical support and encouragement needed when students question whether they can succeed. The high-performance standard (that is, scoring at least a 90 percent) required of students on each quiz helps them learn the level of study necessary to succeed in college, strengthens study skills, and fosters the development of strong study habits. Further, by receiving Amplified Assistance and focusing on mastering one unit at a time, students feel greater control over their learning. Figure 2 and the following video describe the core components of the U-Pace approach.

Figure 2. U-Pace Core Components

Diane Reddy explains the U-Pace approach in this video (4:27 minutes):

Student Outcomes

Extensive evaluation in Introduction to Psychology courses indicates that U-Pace instruction facilitates greater learning and greater academic success for all students compared to conventional, face-to-face instruction.

Diane Reddy explains how U-Pace's effectiveness was thoroughly evaluated in comparison to the conventional teaching approach (6:32 minutes):

Student Academic Success

We compared U-Pace instruction with conventional instruction, holding the course content and textbook constant. In both the U-Pace and conventionally taught course sections, grading was objective and based on students' performance on computer-scored multiple-choice assessments. In addition, assessment questions for U-Pace and the conventionally taught sections were drawn from the same pool of equally difficult test items and used to form either quizzes (for U-Pace students) or larger exams (for conventionally taught students). Final course grades for U-Pace students were based on the number of quizzes completed with a score of at least 90 percent, whereas final course grades for the conventionally taught students were based on the average of their four exam scores.

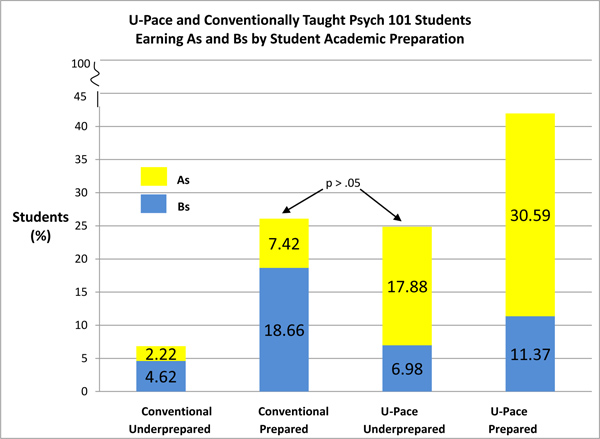

We evaluated whether academic success — defined as an objectively determined final course grade of A or B — would differ between the U-Pace (n = 1,734) and conventionally taught (n = 2,874) students. In addition, we evaluated performance under both instruction types for "academically prepared" students and "academically underprepared" students, who had low standardized test scores for college admission (ACT composite scores of less than 19) and/or cumulative college grade point averages (GPAs) of less than 2.0 on a 0.0–4.0 scale.

As Figure 3 shows, a significantly higher percentage of U-Pace students earned a final course grade of A or B compared to conventionally taught students (χ 2(1) = 137.13, p < .001). Importantly, both academically prepared and academically underprepared students performed better with U-Pace instruction. In fact, as the two middle bars in Figure 3 show, academically underprepared U-Pace students performed as well as the academically prepared, conventionally taught students (χ2(1) = 0.24, p > .05).

Figure 3. Comparing Student Performance and Preparation Approaches

U-Pace instruction facilitated greater academic success for all students and empowered academically underprepared students to perform as well as academically prepared students in conventionally taught sections.

College student Sandy Vue describes how working with U-Pace helped her retain information over time and changed her overall study habits (1:00 minute):

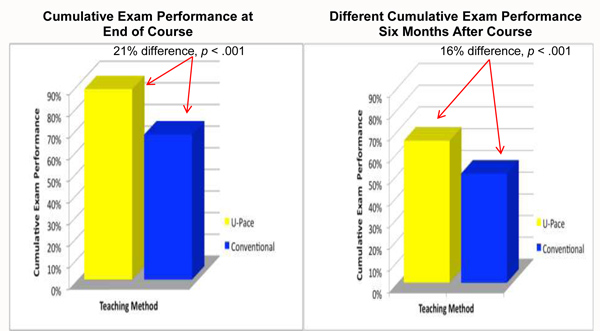

Student Learning

We assessed whether randomly selected U-Pace and conventionally taught students differed in their learning at the course's conclusion and again six months later using two different cumulative, multiple-choice exams measuring core concepts for Introduction to Psychology (see Figure 4). These exams did not count toward U-Pace or conventionally taught students' course grades. A committee of experienced Introduction to Psychology instructors selected core concepts for the exam based on those identified by the American Psychological Association's Society for the Teaching of Psychology, Office of Teaching Resources in Psychology.2 In addition, the exams were constructed so that the questions tested understanding of the material beyond recall of factual knowledge.

Figure 4. Impact of U-Pace on Student Learning

The cumulative exams were administered in a proctored classroom. Students' motivation was maximized by requiring them to put their names on the exams, to work on the exam for a minimum of 30 minutes, and to check over their answers before they could be dismissed and receive their $25 incentive. In addition, students were told that the exam was critical for the evaluation of learning and that it was important for them to perform their best. The U-Pace students significantly outperformed the conventionally taught students, scoring 21 percentage points higher. Six months later, the U-Pace students once again performed significantly better on another proctored cumulative exam measuring core concepts, this time scoring 16 percentage points higher. There were no significant differences in ACT composite scores or cumulative college GPAs to explain the greater learning and greater retention of the material demonstrated by U-Pace students.

Samantha Jackson, a first-generation college student, describes U-Pace's benefits in and beyond the classroom (1:14 minutes):

Adopting the U-Pace Instructional Approach

Consistent with EDUCAUSE's goal to facilitate networking and sharing of technology-based innovations, a U-Pace Community of Practice website (which debuts January 15, 2012) is being developed with support from EDUCAUSE, funded through the Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) grant program. Valuable U-Pace resources will be freely available, including a web-based U-Pace Training Module and the U-Pace Instructional Manual. In addition to reducing instructor preparation time, the U-Pace Instructional Manual provides the opportunity for greater consistency in instruction from semester to semester, discipline to discipline, and institution to institution.

Introduction to Psychology was an excellent context for testing the efficacy of U-Pace versus conventional instruction because most full-time students take the course at some point in their college career. Therefore, the findings of greater learning and greater academic success found with Introduction to Psychology students are likely to be highly generalizable. The U-Pace instructional approach might be most applicable to courses in which student performance can be objectively assessed, particularly with multiple-choice quizzes. For courses that require demonstration of student performance other than through quizzes, the U-Pace approach could be used for portions of the content or in a blended learning format.

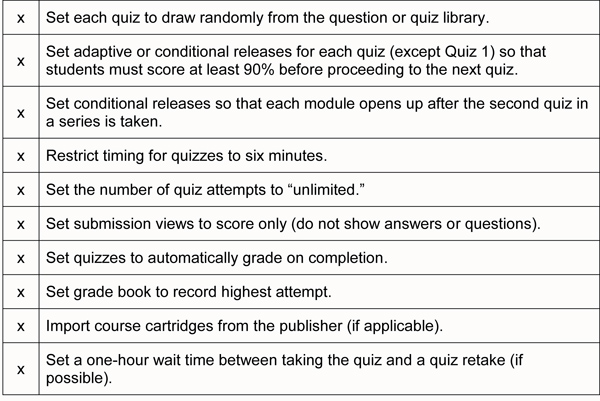

For the mastery-based component of U-Pace, the LMS must be set to meet the critical conditions shown in Figure 5. Depending on the LMS, defaults might also need to be disabled (such as the automatic scoring deduction for retakes). U-Pace instructors must be able to use the LMS to:

- Monitor the progress and number of attempts made by each student on each quiz to provide timely, tailored, and constructive support and encouragement

- View students' correct and incorrect quiz responses in order to give personalized feedback on content not yet mastered

- Use advanced availability features to provide special access to students with disabilities (that is, resetting the time limit on quizzes in accordance with students' accommodations).

Figure 5. Checklist for Critical LMS Settings for a U-Pace Course

Praising student efforts (quiz attempts falling short of 90 percent mastery) and small successes (quiz completions with at least a score of 90 percent) is fundamental to the U-Pace instructional approach. If an instructor believes that praise is justified only for major accomplishments such as completing a substantial portion of the coursework (perhaps because they fear their praise will lose its power, impact, or otherwise lack credibility), they will not successfully implement the U-Pace approach.

Focusing solely on major accomplishments is not only antithetical to U-Pace, it is flawed. Withholding praise until students achieve the ultimate accomplishment is ineffective because the ultimate accomplishment is predicated on many smaller successful approximations.

To successfully implement U-Pace instruction, instructors must also discard the erroneous notion that some students are worthy of praise, support, and encouragement while others are not due to their "lack of accomplishment." In this viewpoint, there is no coaching role for the instructor; instructors are reduced to providing information. So, the instructors set the bar and see who gets over it, without directly facilitating the students' progress. From this perspective, it is not the instructor's role to directly support and encourage students' efforts, particularly if unsuccessful. The U-Pace instructional approach reflects a different perspective. By encouraging students, the U-Pace instructor gives them the "courage" to persist and maintain their effort. Instructors will not lose credibility if their praise of students is contingent on student behavior.

Further Rigorous Evaluations of U-Pace in Progress

With support from the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences, we are conducting a four-year randomized controlled study involving 1,920 undergraduates across three disciplines (psychology, sociology, and political science). The results of this research will reveal whether Amplified Assistance with learning, mastery-based learning, or the combination of these core U-Pace components is responsible for the greater learning and greater academic success associated with U-Pace. This research will also determine whether all students benefit from U-Pace instruction and whether improvements in U-Pace students' perceptions of control over their learning mediate student outcomes. Examining perceived control and its relation to deep learning is essential to increasing student success.

With support from the NGLC grant, we are seeding Introduction to Psychology U-Pace courses in three public universities. In addition, we have trained instructors from 20 other colleges and universities in the U-Pace approach. Evaluation data from this first wave of adopting institutions will determine whether the technology-enabled U-Pace instructional approach is effective across institutions and student populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleague Dylan Barth from the UWM Learning Technology Center for developing the critical conditions checklist. The research reported here was supported by grants from EDUCAUSE Next Generation Learning Challenges and the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences grant no. R305A110112 to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

- Lorin W. Anderson and David R. Krathwohl, eds., A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (New York: Longman, 2001).

- 2. Derrick L. Proctor and Alisa M.E. Williams, "Frequently Cited Concepts in Current Introduction to Psychology Textbooks," Society for the Teaching of Psychology (APA Division 2), Office of Teaching Resources in Psychology (OTRP) (2006).

© 2011 Diane M. Reddy, Raymond Fleming, Laura E. Pedrick, Katie A. Ports, Jessica L. Barnack-Tavlaris, Alicia M. Helion, and Rodney A. Swain. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.