Key Takeaways

- The author, a college professor, made a successful attempt to move from traditional paper exchanges and essay grading to a digital grading system that more closely relates to the world in which today's students live.

- After encountering problems with various methods he tried, he developed a digital grading system using Google's free online applications, including GMail and Google Docs.

- Having established an all-digital classroom with digital methods of exchange and assessment, he foresees future pedagogical uses of these technologies.

Digital what-not is all the rage these days. Digital natives. Digital literacy. Digital classrooms. Digital futures. Digital humanities. This march of technology puts tremendous pressure on all levels of the education system, but I think it puts teachers, like me, into a particularly awkward position. A brave new world is upon us — whether we like it or not, whether we understand it or not — and if we are to reach our students, to make our teaching relevant to them, we have to embrace that world, however stumbling and awkward it might feel. We must find ways to enable our students, as Spencer Dunford put it, to be "better able to succeed in a world where the presence of technology is ever increasing."1

It is one thing to know this — and I think we all do — but it is quite another to know what to do about it. That is, it's difficult to know how to begin to move from our "traditional" modes of teaching to something more suited to this new "digital" world.

I decided to take on the revolution alone, without fancy software and gadgetry, and with only the faintest idea what I was doing. Remarkably (to me at least), I have been somewhat successful in my attempts to incorporate technology into the daily life of my classrooms. In this article I share some of what I am doing, what I have learned, and where I think this is headed.

Experiments in Digital Grading

I am a medievalist by trade. Teaching at a small school, however, I typically do more teaching of core curriculum courses — our English Department has a four-class sequence of composition and literature surveys — than I do of upper-level medieval literature courses. I talk often about basic writing skills, and I grade stacks upon stacks of essays. So I knew that my new digital teaching life would be built around the efficient processing of student papers.

My first foray toward digital grading was to receive electronic copies of student work and then use the "Review" functions in Microsoft Word to correct and comment on them before returning the "marked-up" electronic copies to the students, often using Word's "track changes" feature. This approach is certainly not unique, and I found positives to this system, including that students no longer had to decipher my handwriting. At the same time, the "track changes" method of paper grading had problems. For one thing, it was clunky. If I am going to grade electronically, I need the tool I'm using to get out of my way; I need the program, like the red pen, to "disappear" so that all I have to think about is my grading. That was not happening with Word, in which I spent a lot of time opening and closing files and functions.

One of my biggest worries going into my "grading-with-Word" experiment was that it might inadvertently make coursework more difficult for my students who came from low-income and/or urban backgrounds and thus might not be as familiar with the technology. Happily, my experience agreed with recent studies showing that differences in digital literacy are not strongly tied to socioeconomics.2 Unhappily, my experience showed little difference because a surprisingly large number of my students, regardless of their socioeconomic backgrounds, were hardly adept at using this particular technology. All were familiar with the basic uses of Word, but a much smaller number were comfortable with the extended functions of Review. While surprising to me, this discovery matches recent investigations into how tech-savvy college students really are.3 I thus ended up spending class time showing students how to access my comments. Because the feedback was several steps away, I fear that some students most in need of it never got it. Some of the same concerns applied to my use of Blackboard.

It did not take me long to begin searching for an alternative that would provide the advantages of an e-grading system without so many problems. Because I was doing this on my own, I knew that whatever I came up with needed to be inexpensive. As in free.

Enter Google

Founded in 1998, Google is a collision point for information and technology. By 2010, its data centers were running over 34,000 searches per second, making it arguably the nexus of this extraordinary historical moment in which we find ourselves.4 From my point of view, one of the great things about Google (and I'm not a stockholder) is that many of its services are both free and powerful. GMail, for instance, is the best e-mail service I have ever used: searchable, flexible, and accessible from almost anywhere. In addition, it works digit-in-digit with Google Docs, an online suite of applications, and Google Calendar, now my sole time organizer. All of these services are available via any Internet connection.

While I began my experiments somewhat wary of a "cloud" system, my experience has been that the downtime — periods when I could not access the Internet and do my work — is minimal. In fact, I've never been unable to access my materials. During my experimenting, meanwhile, our campus Blackboard servers were inaccessible several times for maintenance of one kind or another.

GMail

I first fell in love with GMail for its message threading, which allows a simple, sensible view of my electronic communications with students, and for the speed and thoroughness of its search functions. These features, however, are quickly becoming ubiquitous in e-mail programs. What now sets GMail apart are the ways in which it has allowed me to treat e-mail not as a simple message exchange system but as an integral part of my classroom experience, especially when it comes to the exchange of assignments. Students who recognize the untapped pedagogical resource that e-mail represents welcome this approach. A 2008 survey of college students, for instance, found that 67 percent thought e-mail could positively impact student learning, compared with a mere 50 percent of their associated faculty.5 Unlike new-fangled software programs, our students know (and generally adore) e-mail. Even better, they want to use it as part of their education. In making my digital grading system, I knew I wanted to make e-mail an integral part of the process, and GMail gave me the tools.

I use the example of an essay here, only because this is the predominant item I tend to grade. Any writing assignment can be exchanged and assessed in the same way.

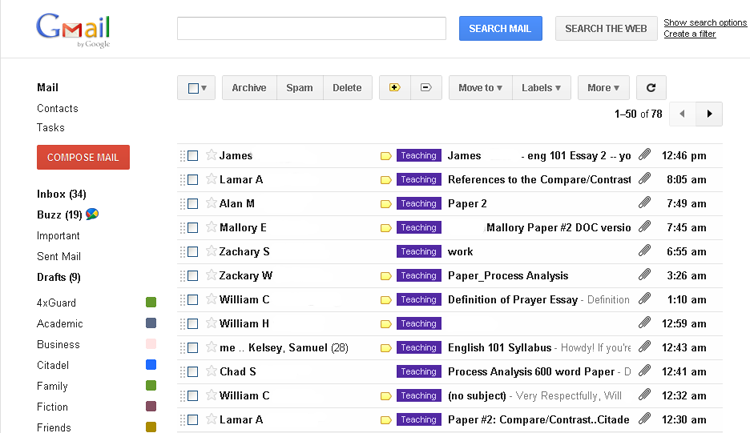

Before class begins on the due date for an assignment, students are expected to e-mail me their work as a .DOC, .DOCX, or .RTF file. When I walk into the classroom and pull out my smartphone, within seconds I can read down the list of e-mails in my inbox to see who has (or has not) turned in the assignment. By glancing at the "paperclip" icon associated with each e-mail, I do not even need to open them to see whether the students properly attached a file (see Figure 1), and the time stamps tell me the time each message was sent. Thus those "Did you get it?" queries from students are cut off before they can begin.

Figure 1. GMail Inbox on an Essay Due Date

After class comes the grading, which I can do anywhere. The papers are all safely on Google's servers, accessible from just about anywhere I can access the Internet.

What I give my students is not traditional line-editing grading, though long before I moved to my digital systems I was abandoning that time-honored method in favor of a more "sparse" grading style in which I pointed out representative errors but otherwise forced the students to find the problems in their work themselves. I also use a five-part rubric of my own design to help provide students with pertinent information about the positives and negatives of their work.

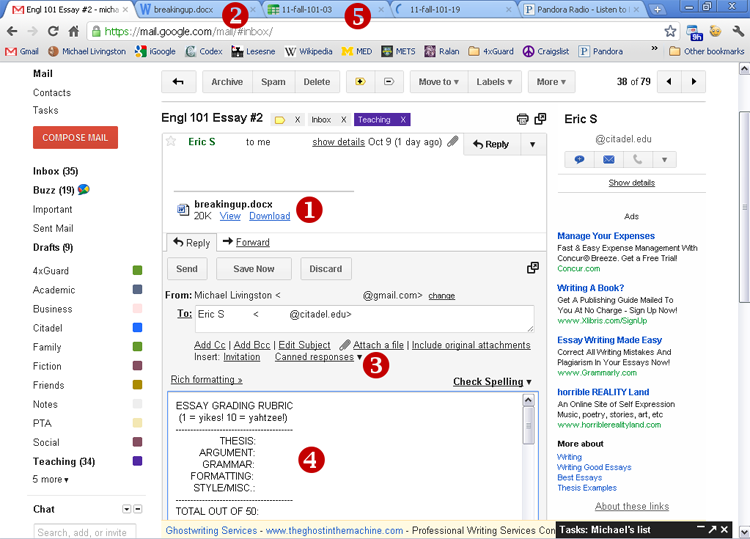

So I sit down and open the first e-mail from a student. Call him Bob. First, I click on the link to his attached paper (see Figure 2, Step 1). This will automatically use Google Docs (more on this shortly) to open the document in a new browser tab or window, enabling me to see quickly whether I do, in fact, have a paper to grade or if I have been sent Biology homework instead (Figure 2, Step 2).

Figure 2. Steps in Grading an essay in GMail

Next, I click "Reply" to the e-mail. If Bob sent me his Biology homework, I send a gentle (or not) e-mail pointing out the problem. If I have a paper to grade, however, I use GMail's "Canned Responses" system to insert, with one click of the mouse, a standard text into my reply e-mail (Figure 2, Step 3). This standard text contains my grading rubric (not yet filled out), an explanation of that rubric, hotlinks to some Internet sites that I tend to refer to quite a bit (like the Online Writing Lab at Purdue), and a space to begin entering my written feedback (Figure 2, Step 4).

Switching back and forth between my browser tabs or windows, I now read through the paper, filling out my grading rubric and then writing what amounts to a "letter" explaining the issues. In a bonus for me and the student, I convey this information through a medium in which they do not need to read my handwriting.

I can also manage quite a few feedback tricks because both texts I am working on are digital. I can copy and paste parts of Bob's essay into my letter, for example, to highlight a positive (or negative) textual moment. I can grab a paragraph of his and set it directly alongside my heavy revision of it. I can paste in a book reference, even a link to the online catalog of the library. And if I suspect plagiarism, I can also rapidly copy a bit of Bob's text and search for it on the Internet.

Google Docs

GMail may be the heart of my grading system, but Google Docs is the lifeblood. I've already mentioned how it allows me to view the documents my students send me, but it is more than a simple viewer: it is actually a fairly well-featured suite of applications. I compose documents on it (as I have in drafting this short essay), and I use it to build intricate, professional slideshow presentations that can be called up virtually anywhere at a moment's notice if I have Internet access (or anywhere at all if I click on a button and download them to a thumb drive or some other portable media).

I also have an online spreadsheet that is as powerful as I could possibly ask for: since 2006 I have thereby stored all of my grades on Google Docs, which has enabled me, more than once, to check and confirm a grade for a student or administrator when I was hundreds or thousands of miles away from my office.

When I'm grading any given paper, then, I have three browser tabs or windows running:

- My reply message to the student (in GMail)

- The student's paper (in GoogleDocs)

- The grade book for the class (also in GoogleDocs)

As soon as I have filled out my rubric and written my e-mail, I take Bob's grade and enter it into the grading spreadsheet (Figure 2, Step 5). This spreadsheet automatically calculates Bob's course grade, itself a handy thing for those catch-the-teacher-on-the-run questions. I double-check the grade between e-mail and spreadsheet. I double-check the student's name between paper and spreadsheet. Then I close Bob's paper, send the e-mail, and pull up another paper.

System Effectiveness and Future Directions

In my classroom, the cumulative effect of this interconnected suite of programs has been to get more useful feedback to the students, more quickly, and in a form they find familiar. Papers are never lost, and — perhaps more importantly — the feedback is never lost. As I am grading Bob's third essay, I can use the threading and searchability of GMail to see, within seconds, exactly what he turned in for his first two papers and what I told him about them. He, of course, can do the same thing. And unlike the method of using "track changes" and commenting through Word, there's no need for Bob to download the essay to his hard drive, hope he has a compatible word processor, open the essay, turn on the function to view changes, and then scroll through the paper looking for the comments (itself a process that may require him to zoom out, change the viewing setting, or scroll to the side of the screen). Instead, Bob can open his e-mail and do a simple search for my name; within seconds he has access to all of my comments on all of his papers. I have the same, of course, and on an expanded scale I am now building a database of student work — a goldmine of material for any self-assessment I might conduct on my methods and courses, or any plans I might make to chart student growth.

All of it free, all of it without IT support, and all of it easy to learn and use.

Best of all, the students seem to love it. In the spring of 2011 I asked the 48 students who took courses from me in the fall of 2010 to fill out an anonymous survey that allowed them to compare my e-grading methods to other methods they had encountered. The results, while hardly scientific, were to my eye very positive, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Student Perceptions of E-Grading Compared to Other Grading Methods

| E-Grading Elements | Worst | Worse | Okay | Better | Best |

| Doing it all by e-mail | 0 | 0 | 25% | 8.3% | 66.7% |

| Speed of feedback | 0 | 0 | 8.3% | 41.7% | 50% |

| Five-part grade breakdown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% | 66.7% |

| Getting whole-paper feedback | 0 | 0 | 16.7% | 25% | 58.3% |

| Getting detailed grammar corrections | 0 | 0 | 7.7% | 38.5% | 53.8% |

While I'd love to rest on those laurels — believe me, I would — the digital grading system described here is only a toe dipped into the pool of pedagogical possibilities offered by these kinds of technologies. As digital literacy grows, so too will our ability — and need — to integrate more digital tools into our teaching.

If students also have Google accounts, then we can leverage the "sharing" function of Google Docs, in which the same file can be accessed by more than one user. The "PowerPoint" lectures I have developed in the system, for instance, could be shared with my students at the click of a button, giving them ready access to printing the lectures out for review and study. Going even further with this sharing feature, an instructor could create a template for a given writing assignment in Google Docs and then share a copy of the document with each of his or her students. From that point forward, the instructor and student would both be able to directly access the same document file (though the instructor, as the "owner" of the file, could "lock out" the student from working on it at any point, a potentially important feature). Changes made by one party to the document, or comments, would be instantly viewable to the other party. This document sharing could thus be used in the final assessment process, perhaps replacing the e-mail exchange described above.

These same capabilities are amplified if students compose their work in a shared Google Doc. Because of the way the application tracks document changes, the instructor could see the entire process of document creation, from the initial tentative steps of brainstorming through the various stages of drafting and revision. Taken a step further, the instructor could selectively add more students to a shared document, bringing peer-review or collaborative work into a controlled and analyzable fold. Simply put, this "sharing" capability within Google Docs is an enormously powerful pedagogical tool. We just need to harness it.

#

I am not going to say that our future is here — that would be nonsense. But I do think it is true that the future is coming faster than ever, and we need to start worrying about it today.

Though we cannot take this digital world in all at once, we can — like that old adage about how to eat an elephant — take it one small bite (or byte) at a time. And if a medievalist can start chewing on it, I suspect you can, too.

Visit my website at http://www.michaellivingston.com/.

- Spencer Dunford, "Reviewing Student Papers Electronically," English Journal, Vol. 100, No. 5 (May 2011), pp. 71–74; see p. 74.

- Christine Greenhow, J. D. Walker, and Seongdok Kim, "Millennial Learners and Net-Savvy Teens? Examining Internet Use among Low-Income Students," Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, Vol. 26, No. 2 (2009/10), pp. 63–68.

- Anoush Margaryan, Allison Littlejohn, and Gabrielle Vojt, "Are Digital Natives a Myth or Reality? University Students' Use of Digital Technologies," Computers & Education, Vol. 56, No. 2 (2011), pp. 429–440.

- Matt McGee, "By the Numbers: Twitter Vs. Facebook Vs. Google Buzz," Searchengineland.com, February 23, 2010.

- Meredith Weiss and Dana Hanson-Baldauf, "E-Mail in Academia: Expectations, Use, and Instructional Impact," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2008), pp. 42–50.

© 2011 Michael Livingston. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.