Key Takeaways

- Global public health as a course domain topic suits the various pedagogical methods and technologies commonly used for online learning.

- The data-rich technologies implemented for global public health projects can also enrich an online course covering the topic.

- Open-source content from federal agencies and reputable health organizations helps emphasize the complexity of global public health issues.

- A game model incorporating some principles and practices of global public health can raise awareness of important health issues among those who become engaged in playing it.

As a college course, global public health covers topics that affect individuals' welfare and thus should be accessible to the public, providing information to help people make informed decisions about their health. This goal underlay the creation of DMP 844: Global Health, a graduate-level course in the College of Veterinary Medicine's Department of Diagnostic Medicine/Pathobiology (DMP) at Kansas State University. The course also includes a light-hearted but engaging game titled "Where in the World is Dr. Salus 'Dynamica' Mundi?" (Figure 1), which highlights some basic premises of global public health.

Figure 1. Screenshot from "Where in the World Is Dr. Salus 'Dynamica' Mundi?"

The Online Graduate Course on Global Health

Beginning in the fall 2010 semester, instructional designer Shalin Hai-Jew and educational videographer Brent A. Anders met with Dr. Deborah J. Briggs to begin planning creation of the 3-credit course DMP 844: Global Health. The target learners for this course would be graduate students in veterinary medicine or the Masters of Public Health program.

Theirs would be a collaboration across distance because the principal investigator, Dr. Briggs, lived abroad and traveled widely for her global work in rabies prevention with the Global Alliance for Rabies Control, of which she is the founding director and executive director. Further, it would be a mediated virtual collaboration across time, with early interactions to become familiar with each other's work styles. Other virtual meetings discussed early considerations for lecture-capture and other technologies, some early planning, and later planning to actualize the course build.

Various types of technologies supported this remote collaboration work. First, a course shell served as a shared course work site on the Axio Learning course management system (CMS). The team used the site to share files and for some intercommunication. Second, public file-sharing work sites enabled the sharing of larger files. Other digital files were shared in-person through memory devices. Telephone and e-mail communications helped coordinate work. And over the lifespan of the project, the team members met a few times, whenever Dr. Briggs was stateside.

The official course description reads:

"Global Public Health" includes a review of how economic and political factors have and continue to affect global public health. The course outlines the major players in global public health and their various roles. The course also explains epidemiological profiles of disease and how they differ in low-, medium-, and high-income countries and how the structure of societies influences the state of public health in these populations, including the role of social inequalities in explaining persistent differences in health status. The class will learn public health outcomes after ecological disasters and how the cost to human life and suffering can be reduced through political and social structures and reactions. Additionally, the course focuses on the link between neoliberal globalization and illness, death, and injury and discuss how neoliberal globalization affects the work place and occupational safety. Students will learn how globalization influences public health and how it has the potential to benefit and harm population health. Students will also learn how international occupational health and safety is a critically neglected area of global health. The course will provide a description of some different types of health care systems, health care reform systems, and concepts. The course stresses the fact that although the control of diseases is an important factor in improving the health of a population, it is not the only factor that one needs to consider when strategically developing health plans. It provides examples of some developing countries that have made extraordinary gains in health conditions and have done so through investing broadly in the social welfare of their citizens. It also explains how collective commitment to social justice and equity through social action and grassroots organizing, in addition to more formal political channels, is essential in the making of healthy societies.

A Modular Structure

The approved course was designed around specific learning objectives, and the course modules were designed to meet those objectives:

Module 1: Historic Origins of International Public Health

Module 2: The Organization and Logistics of Health Systems and International Health Agencies

Module 3: Politics, Health, and Development

Module 4: Data Collection and Profiles of Disease

Module 5: Society, Culture, and Health

Module 6: Health under Crisis

Module 7: The Impact of Globalization on Public Health

Module 8: Economics, Health, and Health Care Systems

Module 9: Successful Policies for Health

The modules have an implied chronology, beginning with the origins of international public health and the structures created for achieving global public health. Then come descriptions of the different methodologies used to collect relevant data about global public health. The later modules describe the challenges of global public health in terms of economics (and especially poverty), globalization, emergent diseases, and political decision making. Then, based on the body of history and learning, the final module investigates optimal policies for global health. Learners explore the various theories and models behind global public health, and they also discover how global decision making occurs to set health priorities.

Each module includes the following elements: an introduction to the topic in the form of a navigable and interactive module; some internally created videos along with publicly available and open-source videos (such as podcasts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and even public organizations), with some videos posted on YouTube. The interests of federal and local governments in public health yielded a wide range of open-source content. International agencies focused on public health also often had generous public-use policies for their information graphics, photographs, information, and videos. Each module also included several reading assignments from Textbook of International Health: Global Public Health in a Dynamic World, by Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Yogan Pillay, and Timothy H. Holtz (Third Edition, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-530027-7). In-depth discussion assignments would be posted to shared spaces on a message board, and a quiz covered the information in each module. In addition, the students were to complete three research-based analytical activities and one term research paper (focused on one aspect of global public health that a student wanted to pursue for their own learning and future career).

Online Resources for Public Health

Core public health information resources online include:

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- The CDC Public Health Image Library (PHIL)

- CDC Podcasts

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)

- PubMed.gov (US National Library of Medicine/National Institutes of Health)

Course Grading

The course grading was based on the work tasks shown in Table 1, with a total of 300 points possible, plus some extra credit points for learner engagement. The three activities include a range of choices based on particular aspects of global public health. The comprehension quizzes reinforced understanding of each module's content. The term paper enabled more customized learner explorations of particular topics and allowed the instructor to provide direct feedback on the research work. The discussion questions encouraged learner interactivity with other students and highlighted the various backgrounds of the respective learners.

Table 1. Grading for Public Health Course

| Student Work | Points | Percentage of Total Course Grade |

| Three activities (Dropbox assignments) | 57 (19 points each) | 18% |

| Quizzes (9 total, 1 per module) | 45 points (5 points each) | 15% |

| Term Paper | 100 | 33% |

| Discussion questions in message board/Participation (per module) (9 topics) | 100 points total | 33% |

| Total | 300 points possible* | 100% possible |

A full syllabus of the first offering of the course (Fall 2011) is available here.

Social Presence and Learner Interactivity Design

The human element is a critical part of student learning and retention. In that spirit, the social presence of Dr. Briggs was deliberately constructed to explain her global health work in rabies and to humanize her insights by the inclusion of some of her photographs (see Figure 2) in the modules and a studio-based video interview in which she talked about her work. (The following videos were captured by Brent A. Anders in his studio at K-State.)

Figure 2. Dr. Deborah Briggs

Dr. Deborah Briggs Introduces Herself (2:41 minutes):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs explains global public health (3:55 minutes):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs discusses global public health and international travel (4:59):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs talks about international agencies for global public health (9:47 minutes):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs explains some long-term challenges in global public health (10:01 minutes):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs advises professionals on staying relevant in global public health work (3:20 minutes):

Transcript

Dr. Briggs emphasizes the importance of engaging the world in public health issues (5:33 minutes):

Transcript

By design, the discussion questions, activities, and term project involve a fair amount of customized instructor interaction and feedback to support the unique interests of the learners. To accommodate the various time zones, no synchronous (shared real-time) or co-located (shared real-space) activities were required.

Further, to emphasize the worldwide nature of global public health, the development team captured slideshows that highlighted some of Dr. Briggs's travels for work. More interactivity could be built into this course, such as having online specialists presenting live web conferences on their areas of expertise. An extensive site on rabies (Figure 3), for example, offers multiple opportunities for public engagement.

Figure 3. Public Information on Rabies Prevention

The Fit of Global Public Health to Online Learning

The breadth of global public health means that it attracts people from various fields. Some hail directly from public health, with backgrounds in human health, veterinary medicine, and epidemiology. There are laboratory workers and researchers. There are those who work in food safety and security. Others work in national security. Still others work in the pharmaceutical industry. Some public health workers specialize in crisis communications. Others create visuals to communicate healthcare messages to increase accessibility for those from a variety of language and literacy backgrounds.1 Public health attracts learners with wide-ranging interests and backgrounds. The growing challenges in this field require that practitioners in every aspect share their knowledge and expertise with others in the field—in order to promote more effective public health (surveillance for emergent diseases, cooperation for emergency responses, and others).

Global public health is well situated for teaching and learning opportunities through online means. The distance aspect of the collaborative technologies enabled connections across distances and the different cultures and geographies of the learners — to promote deeper understandings of public health practices in many societies.

Further, the assignments — particular the term research project—enabled customization to the unique circumstances of the learners. The research could entail inclusion of trips to local areas where public health practices are done. Global health is both global and local (thus the "glocal" term), and the online course could reflect this. Evelyne De Leeuw defines health as a "multi-causal phenomenon" based on a variety of factors, including urban design and management.2 At the lived level, an individual's health depends on behaviors, genetics, lifestyle choices, and exposures to diseases. At the social level, there are issues of education, poverty or wealth, as well as systemic issues of clean water, sanitation, and governance. Then, too, the larger environment affects individual health.

The overall wealth and organization of a society also affect public health. Even within a society, relative wealth has statistical correlations to various types of health well-being. Many developing countries or those in the "Global South" are dealing with health challenges that have already been "solved":

Ninety percent of all infectious disease deaths are caused by diseases that have been nearly eliminated in more affluent nations (Global Health Council 2002) and communicable diseases are eight times more likely to cause death in low-income countries than in wealthier ones (WHO 2002).3

While good practices may migrate from developed countries to less developed ones, there have been more negative exports in terms of public health. Obesity has been a growing public health issue in the world because of an imbalance of energy intake and more sedentary lifestyles4 and global media and television advertising linked to "consumption of higher-fat foods."5

Online Tools for Global Public Health

In the same way that information and communication technology (ICT) helps disseminate information to various publics, these technologies enable the same affordances for learning about global public health. This field is data-rich, and ICT can present healthcare simulations and modeling, statistics, trend lines, population statistics, and other complex data in easy-to-understand ways using visual information design. In addition, online tools such as Google Translate enable the easy deployment of information in multiple languages.

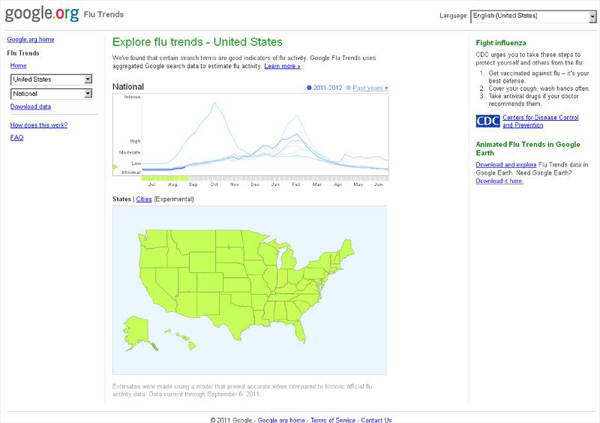

With fast-moving changes in public health issues — such as during contagious disease outbreaks — new information may be easily integrated into an online course by adding informative links and interactive real-time maps, for real-time situational awareness. The culling of health information from Google searches and Twitter feeds is becoming more common as creative forms of informatics.6 Comparing search-term frequencies for influenza in Twitter with the statistics for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found a .78 correlation and near-real-time surveillance potential.7 Google's Flu Trends found correlations between flu activity and searches for flu-related terms (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Google Search-Term Frequencies for Influenza

In global public health, various ICT tools have been deployed for information collection, data analysis, and decision making. Decision-making systems have been developed for situations of time and resource constraints. Health information systems distribute relevant health data. Various models have been created to emulate human interactions and social relationships — in particular health contexts — such as the middle of an avian flu pandemic; these models test out social networking theories of close ties and influenza transfer risks. There are tools for emergency alerts. Other tools troll the open and Social Web for information indicative of an unfolding health situation as part of general surveillance and real-time situational awareness.

The Game: "Where in the World is Dr. Salus 'Dynamica' Mundi?"

After building the global health course, a reconfigured development team came on board to create a game for general readers to learn more about some of the tenets of global public health. This game is based around a globe-trotting global health expert, Dr. World "Dynamic" Health, being pursued by an intrepid reporter who wants to achieve a scoop (Figure 5):

Global health expert Dr. Salus "Dynamica" Mundi could be anywhere in the world, but ace reporter Nina Novus must find her! Be part of the solution and join the excitement as you help Nina Novus get the scoop of her career by going through the game's clues to help locate the elusive Dr. Mundi.

Conclusion

The nature of global public health and the widespread availability of high-quality factual information in digital form by credible governmental organizations has enabled the smooth creation of the graduate-level DMP 844: Global Health course at Kansas State University. Identifying such critical nexuses for online learning course development may smooth out the creation of such courses and their delivery, maximizing the digital and physical resources available for a given topic.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article and game is informational only; it does not comprise any kind of advisement. Readers use this information at their own risk.

- Jim Bolek and Jamie Cowgill, "Development of a Symbol System for Use in the Health Care Industry," Proceedings of the 2005 Conference on Designing for User eXperience (New York: American Institute of Graphic Arts, 2005).

- Evelyne de Leeuw, "Global and Local (glocal) Health: The WHO Healthy Cities Programme," Global Changes & Human Health, Vol. 2, No. 1 (2001), pp. 34–45; see p. 36.

- Helene D. Gayle and Sanjay Sinho, "CARE: The Contribution of an International NGO to Global Health," in Igniting the Power of Community: The Role of CBOs and NGOs in Global Public Health, P. A. Gaist, ed. (Springer Science+Business Media, 2010), pp. 229–246.

- Vicki L. Collie-Akers and Stephen B. Fawcett, "Preventing Childhood Obesity Through Collaborative Public Health Action in Communities," Handbook of Childhood and Adolescent Obesity, Issues in Clinical Child Psychology: vol. V (2009), pp. 351–368.

- Collie-Akers and Fawcett, "Preventing Childhood Obesity," p. 352.

- Aron Culotta, "Towards Detecting Influenza Epidemics by Analyzing Twitter Messages," Proceedings of the First Workshop on Social Media Analytics (New York: ACM, 2010), pp. 115–122.

© 2011 Brent A. Anders, Deborah J. Briggs, Shalin Hai-Jew, Zachary Caby, and Mary Werick. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.