Key Takeaways

- Increasing instructor-student interactions and improving support personnel interventions with students positively affects their academic performance, retention, and graduation rates.

- A collaborative effort among the academic, functional, and IT units at Northern Arizona University produced a robust course feedback system for faculty called GPS, for Grade Performance Status.

- GPS allows an instructor to send positive, negative, or neutral feedback to students according to their performance in the course.

- An instructor's feedback is available to the individual student and also to university personnel, facilitating a complete support network for all students.

Grade Performance Status (GPS) is Northern Arizona University's new online, academic early alert tool for increasing instructor feedback and facilitating instructor-student interactions. Built as an Oracle PeopleSoft Campus Solutions bolt-on, GPS duplicates the course roster with online submission forms for each student in the class. From the Campus Solutions faculty center page, instructors can access the GPS interface and select automated comments of general concern for attendance and grade with a click of a checkbox. They can also type in personalized comments for grade, academic concerns, and positive feedback.

Grades, GPS, and FERPA

- Grade information is not displayed in the text of the GPS e-mail.

- A hyperlink in the e-mail requires student authentication and verifies the student message ID with the sign-in ID.

- With approved authentication, a secure view of the student records system reveals the grade information.

Students receive instructor feedback in the form of GPS e-mails sent from the instructor's mailbox so that replies connect the student directly with the instructor. Though the primary focus is on instructor-student interaction, GPS also creates an entire network of information for students, instructors, and university personnel. Notifications of GPS messages are posted in the students' MyNAU student portal to prompt them to check their e-mail. In addition to the personalized instructor comments, the e-mails contain action prompts, important university deadlines, and links to the GPS student web pages, which connect students with NAU resources. A history record is generated within the GPS roster for instructors, giving them instant review of previously sent comments and allowing for modification or intensification of their comments over time. Finally, each GPS entry is documented in the student's online records. This makes instructors' feedback available for advisors, student service personnel, and administrators.

GPS use is voluntary. Instructors choose when and how they use GPS, but to prevent desensitization, an instructor may send only one GPS message each week to a student in his or her course. Instructors can send single GPS messages as needed, or they can update an entire class at "checkpoints," sending 100 GPS messages in as little as 10 minutes. First, the instructor enters individualized comments expressing concern for struggling students and possibly creates positive feedback for exemplary performance by other students. A "send all unsent" button delivers these messages first. The instructor uses the "blast" button to send a neutral message to all remaining students, indicating their performance has been reviewed without raising any concerns. A checkpoint is the only time that instructors can send the neutral message. Students know they should consider this system message good news, although these messages are not added to the students' records.

How GPS Works (2010 Faculty Orientation Video)

Transcription for How GPS Works (also a Word doc)

GPS went university-wide in fall of 2010 — three years ahead of schedule. Proven scalability and a successful pilot with 5,000 students increased administrative demand, but a primary reason for wider implementation was to countermand the perception that GPS served only "at-risk" students. NAU does provide direct support for identified at-risk student populations, but risk is a contextual state that all learners can move in and out of,1 and GPS was always intended to provide support for all learners.

GPS is now available for every undergraduate course across all 34 NAU campuses, regardless of length of course or mode of delivery — online, hybrid, or in-person. Every one of NAU's 19,000 students, undergraduate or graduate, enrolled in undergraduate-level courses is currently eligible for GPS messages.

Fall 2009 GPS Pilot

GPS was tested for technical functioning in five courses during the summer sessions of 2009, and the official pilot test was conducted during the 2009–2010 academic year. The pilot was limited to 5,000 students comprised of freshmen, students affiliated with Educational Support Services, and probation and transfer students in some of the colleges enrolled in regular 16-week classes on the Flagstaff Mountain campus. Instructor inclusion required having at least one pre-identified GPS student in a class, and system availability was originally constrained to three designated checkpoints in a term. An average of 200 instructors participated in each term of the pilot, sending a total of 13,000 GPS e-mails to almost 4,000 students. GPS usage — which was and is voluntary — measured 20 percent for the pilot, and instructor satisfaction reached 70 percent.2

InsideNAU Video with Theresa Bierer, 2009

Transcription for InsideNAU (also a Word doc)

Results for the First 10 Weeks Fall 2010

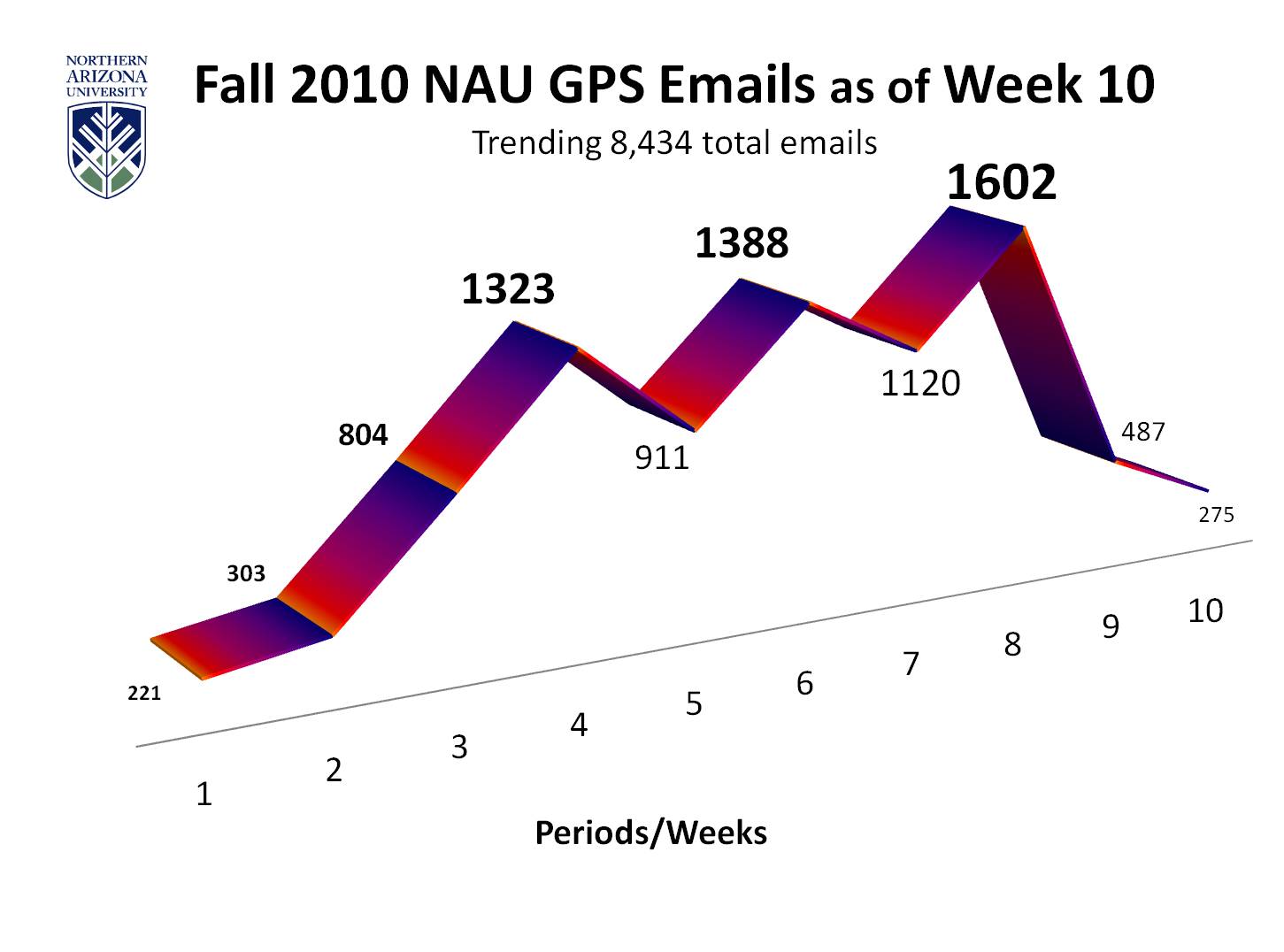

NAU currently uses GPS Version 12, which is available for 1,800 instructors and 19,000 undergraduate students. Instructors received an introductory e-mail on the second day of classes. The first three weeks' commentary focused on attendance issues. GPS reminders were sent to instructors in weeks 3, 5, and 7, and GPS will remain "on" for the duration of the term. In the first 10 weeks, 296 instructors in 488 classes on multiple campuses sent 8,434 e-mails containing 11,817 messages to 5,554 students, with an average of nearly 850 e-mails a week (see Figure 1).3

Figure 1. GPS E-mails, Weeks 1–10 of the Fall 2010 Pilot

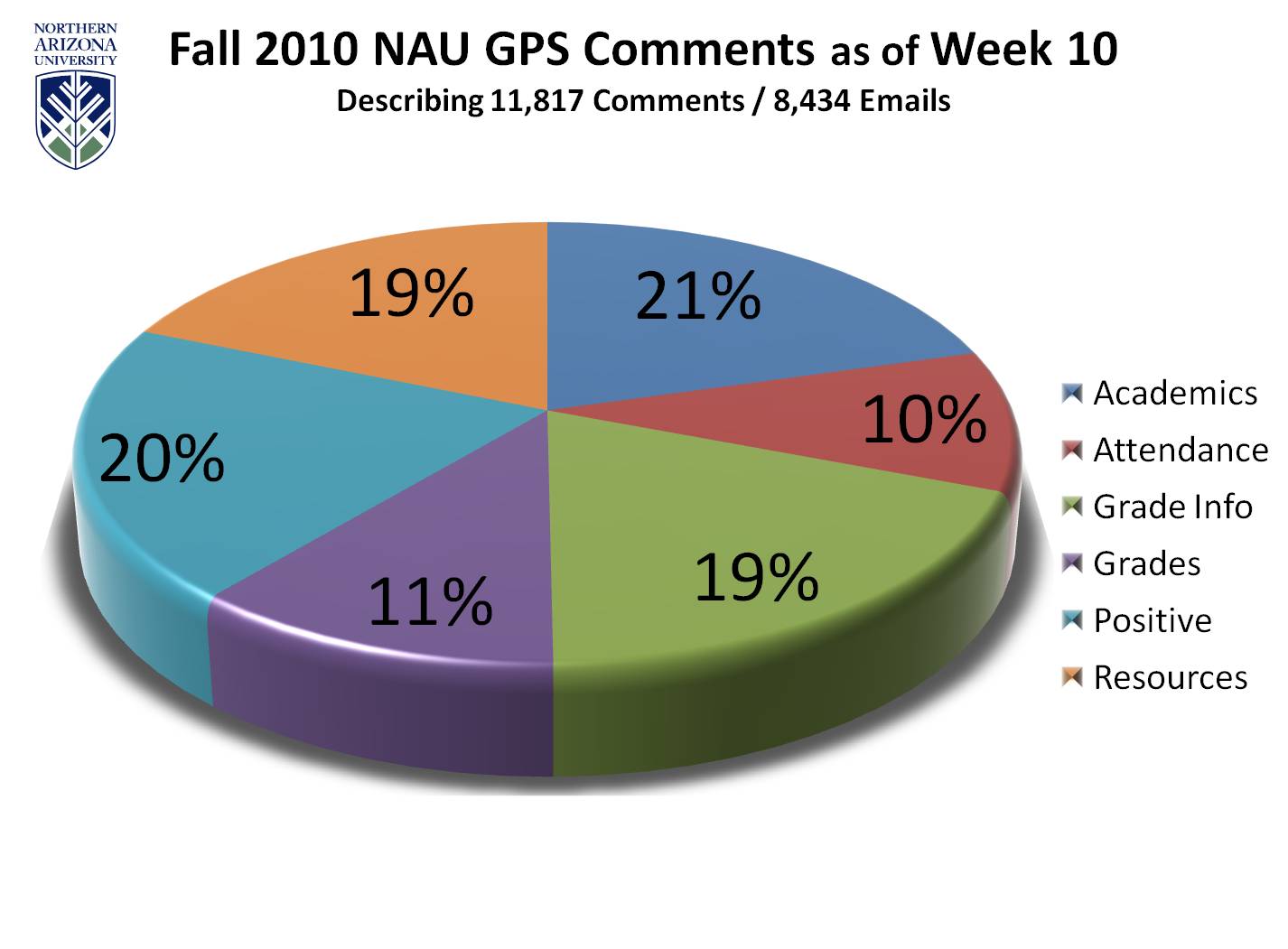

Comments reflect the specific categorization of communications within the e-mails. A single e-mail can contain five comments. Attendance, Academics, and Grade Info are grouped as "concerning," Positive Feedback is "positive," Resources are "neutral," and Grades are "ambiguous" because any grade from A to F can be entered. An interesting development is that 52 percent of the comments were personalized, as Academics, Grades, and Positive Feedback require a typed entry from the instructor.4

Figure 2. GPS Comments as of Week 10 of the Fall 2010 Pilot

Given that GPS had a "soft" rollout for fall, the initial adoption has been promising — 16 percent of the 1,800 eligible instructors have already used GPS this term. In the first eight weeks, GPS averaged 20 new users per week. Currently a total of 180 new users have used GPS in addition to 116 returning from the functional pilot in 2009. With official marketing beginning in spring 2010, the 20 percent usage goal for the first year seems achievable. Because of instructor/student ratios, an exponential factor affects the number of students receiving GPS messages. Almost 30 percent of eligible NAU students have already received at least one GPS e-mail this term.5

Context for Developing GPS

The conversation is the relationship.

— David Whyte, from a keynote address at TEC6

The current fiscal environment for institutions of higher education is one of shrinking resources and increased scrutiny as various stakeholders express their expectation of accountability.7 Questions about retention and graduation rates come from all factions, including prospective students and their families, legislators, benefactors, and accreditation bodies.8

Given this climate, it is not surprising that institutions invest their resources in finding ways to increase student retention and graduation rates. What was once considered the responsibility of student service professionals has become the business of everyone in the university: students, faculty, staff, IT professionals, and administrators.9 Research identifies engagement as a critical factor in improved retention, with emphasis on the relationships that a student develops with individuals and the institution.10 These relationships and the conversations that create them are imperative because our "very lives succeed or fail gradually, then suddenly, one conversation at a time."11

NAU, one of Arizona's three public research institutions, emphasizes a caring faculty, generally smaller classes, and high levels of instructor-student interaction. NAU also fosters innovative initiatives and piloted its first online early alert system in 1996. At that time, instructors submitted (electronic) messages about specific students in the freshman population for follow up by advisors and student service personnel. Though the system operated for 10 years, its effectiveness proved minimal due to technical and interpersonal limitations.

Given the importance of feedback in academic performance12 and engagement in student retention,13 the intention behind the original early alert paradigm was good. However, the effects of the first early alert communications were generally disruptive in NAU's culture. A primary impediment was a convoluted and seemingly misdirected flow of communication. Upon reviewing an instructor's concerns, nine times out of ten, the advice given a student was, "You need to talk with your instructor." Reflectively, many students responded to the interventions with the question, "Why didn't the instructor just tell me this herself?" Many instructors would not use the system, citing their preference to communicate directly with students and recommend corrective action. And advisors found that providing timely feedback coupled with the "big brother" feel of their communications actually damaged advisor-student relationships. When the new design team convened in 2007, the first clear functional requirement was to change the paradigm and create a system that promoted direct communication between instructors and students.

Facilitating the Conversation Between Instructors and Students

Research supports the importance of instructor-student interactions across multiple measures of student success, including "degree aspirations, self-efficacy and esteem, academic success, satisfaction, goal development, and adjustment to college."14 Within the context of pedagogy, the conversation between instructor and student, in the forms of feedback and assessment, is another critical factor in student achievement.15 Formative feedback is especially powerful, providing information that allows for correction before the summative or final assessment.16 While GPS does not provide a tool for feedback on a specific assignment, the instructors on the GPS design team quickly recognized its potential to initiate timely, formative feedback in relation to general student behaviors or trends in performance, which could increase a student's overall achievement.

The general expectation for GPS is that its increased usage by instructors will correlate with changes in various measures of students' behaviors and success. Examples include increases in:

- Informal and formal instructor-student interactions

- Student use of academic resources like supplemental instruction and the Student Learning Center

- Retention and graduation rates

And decreases in:

- D's and F's in high D-F courses

- Petitions for grade changes or withdrawals

- The percentage of students placed on probation or academically suspended

While NAU will begin full analysis of success metrics at the close of the fall term, 60 percent of the 2009 pilot faculty surveys indicated an increase in frequency of student responses. Anecdotal commentary gathered via instructor communications indicates that this trend will likely hold true for 2010.

This increase in instructor-student interactions is not viewed as a positive by all instructors. In a time of budget cuts and increased teaching loads, the prospect of fielding student responses can seem burdensome for those who have not yet tried the tool. Use of GPS is voluntary, however, and instructors control the timing, frequency, and volume of their participation. For the most part, instructors who use the checkpoint feature have in-depth interactions only with those students experiencing difficulties.

In the following clip, Assistant Clinical Professor Nicole O'Grady shares her experiences, student responses, and some unexpected reciprocity in regard to positive feedback at a recent GPS panel:

Nicole O'Grady

Transcription of Nicole O'Grady Video (Word doc)

Faculty Comments

"I have found the new GPS system extremely easy to use and the student response has been tremendous. Normally, I receive a response from a student within 24 hours, and a majority are quite surprised that we instructors contact them."

Richard Holloway, Biology, and member of the GPS Design Team"In time GPS has the potential to offer NAU teachers and administrators a far richer understanding of each individual student's history. GPS could be a key part of our continued efforts to retain and graduate more students, offering them another form of strong institutional support from their freshman year through to graduation."

Laura Gray-Rosendale, English"Thank you, for this tool. I've used it in my course three times already, and I think it will have a positive effect on student participation. I have always sent emails to students who missed an assignment but did not always get responses from them. I think that the GPS emails seem more official to the students. In any case, all of the emails I sent through the system garnered responses."

Alison Brown, Comparative Studies

Student Use of Resources and Conversations with Student Service Personnel

A huge benefit of technology is its ability to layer resources and support onto a single communication. Not every GPS message requires a student's direct response to the instructor. Many GPS messages are prompts to complete or turn in missing work or seek additional academic support. In these instances, students complete the recommended action or connect with other resources. Every GPS e-mail contains links to a student website that centralizes NAU resources. Some students use online information and strategies to self-assess and self-regulate. During the pilot, 26 percent of students clicked through to the resources, and 95 percent of the student feedback garnered from a feedback option on each GPS web page has been positive in regards to finding useful information.17

The ability to access information is imperative to good decision making, and an advantage of the website is the ability to connect students with a broad scope of resources for an array of academic and personal issues. Many times academic struggle is a symptom of non-academic issues such as a personal crisis, illness, or overwhelming stress. In addition to academic support, NAU students receiving GPS messages also receive access to the entire range of services provided by the university community, such as health and wellness, family services, and career counseling.

A university is comprised of an entire network of individuals with the potential to form relationships with students, guide student success, and improve overall retention. GPS leverages this available network by duplicating the content of instructors' messages in the online student record system. A standard protocol for advisors and other student services personnel meeting with students is to review the notes in the student record system prior to the meeting. GPS messages are now a part of these reviews.

Ask a student how classes are going, and the typical response is "Good." With access to GPS instructor feedback, the veracity of such statements can immediately be checked without having to wait for the posting of midterm grades. Advisors and student service personnel can reinforce instructor feedback, offering congratulations for positive feedback and discussing options to address posted concerns. Even a single posted concern opens the door for advisors to ask if this is a singular occurrence or a constant difficulty for a student. The more information advisors have, the more robust their conversations with students can be. An unanticipated advantage is the ability to gather information about students' responses and perceptions of GPS.

In the following audio clip from a recent GPS panel, Career and Academic Advising Coordinator Lela Montfort of the Gateway Student Success Center discusses the effects of GPS in advising conversations:

Lela Montfort

Transcription of Lela Montfort Video (Word doc)

As mentioned by Lela, another advantage of the GPS system is its ability to triangulate information from multiple sources to reveal trends and patterns in student behavior. Sometimes such trends are evidence of a broader issue affecting academic performance such as depression or an unmanageable work schedule. When instructors say that they don't need GPS because they already communicate with their students, this ability to add to a complete profile of student performance provides a reason to reconsider that refusal. Often a student's struggles are attributed to content difficulties or lack of effort. What the instructor might not know is that their seemingly appropriate academic referral does not address the student's personal issue. On the flip side, some students revert to blame or denial instead of confronting their own poor habits. Feedback from multiple instructors all saying the same thing helps place the focus where it belongs. In all instances, staff can strengthen instructor efforts with personalized, relevant action plans and better student support. Additionally, college and department reports generated from the GPS data support targeted outreach efforts, creating even more opportunities for supportive conversations.

Student Comments Shared with Advisors

"I met with a student who had a GPS Positive Update. When I asked her about it, she said she loved it because she was not sure how she was doing and she thought as a college student it would be very 'high school' of her to ask her professor. Now she feels like she can discuss those things with all of her professors!"

Linda Barker, Advisor"When I asked about a student's midterm grade of a D in math, he told me that he didn't feel it would be a concern in the future because 'I got this [GPS] email from my professor that told me to come and talk to him.' After talking with the instructor, the student is attending the SI classes, working with tutoring, and going to the professor's office to check homework answers before class. He is now hoping to pull his grade up to a B, 'which is cool 'cause my roommate said I should just drop the class.'"

Lela Montfort, Advisor"When I asked a young man if he had seen his positive GPS updates, he smiled, sat up a bit straighter, and said, 'Yes I did. It was a nice surprise because I didn't even think the instructors knew my name.'"

Kathleen Day, Advisor

What's Next for GPS?

Now that the GPS design is pretty well stabilized, in-depth analysis of GPS impacts will begin with the conclusion of the 2010 fall term. Planned improvements include a new student website called Resource Connect, which will offer centralized resources for all NAU students and host the new landing pages for GPS. It is scheduled to go live in spring 2011.

A preliminary design has already been identified that would enable GPS to become an official grade input screen, with possible delivery in 2011. Once NAU's conversion to a new learning management system is complete, GPS will begin integrating analytic factors into GPS messages, most likely in 2012. In addition, design of a graduate student version of GPS will begin in fall 2011, with an expected delivery of fall 2012.

While GPS, as a tool, can increase the number of instructor-student interactions, the real transformative power lies in the quality of those interactions and the subsequent relationships formed. An e-mail from Professor Chris Downum revealed how he used the information from GPS-generated conversations:

"The students really took the messages seriously, and appreciated being contacted, and many of them opened up about personal problems or other factors that were interfering with their grades. Based on their emails I've met with several of them and I've worked out some of the problems with their mid-term grades (for example, I offered an amnesty program for those who missed turning in their first written assignment — this seemed fair because many of them were freshmen and hadn't realized [apparently] how important the assignments would be to their overall grade)."

Chris could have let the zeros stand. But subsequent papers proved this was an issue of contextual maturity and not student capability, so he opted to create a collaborative relationship with his students for their success. By leveraging instructor feedback and relationships, informing advising and interventions, and connecting students to options and resources, GPS is shaping student success one conversation at a time.

Interested readers should contact the authors for more information or consultation on GPS:

Mikhael Star, [email protected]

Lanita Collette, [email protected]

- Gwyneth Hughes, "Using Blended Learning to Increase Learner Support and Improve Retention," Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 12, no. 3 (May/June 2007), pp. 349–363.

- Data is from unpublished GPS System Reports including Faculty Survey Results for the2009-2010 pilot.

- Data is from unpublished GPS System Reports for 2010-2011.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David Whyte, keynote address at TEC, quoted in the introduction to Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work and in Life One Conversation at a Time, Susan Scott (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2004), p. 6.

- Vincent J. Tinto, "Research and Practice of Student Retention: What Next?" College Student Retention, vol. 8, no. 1 (2006–2007), pp. 1–19.

- Deborah Hirsh, "Access to a College Degree or Just College Debt?" New England Journal of Higher Education, 23, no. 2 (2008), 17-18.

- Tinto, "Research and Practice of Student Retention: What Next?"; and Mark Nichols, "Student Perceptions of Support Services and the Influence of Targeted Interventions on Retention in Distance Education," Distance Education, vol. 31, no. 1 (May 2010), pp. 93–113; and Nichols, "Student Perceptions of Support Services."

- Tinto, "Research and Practice of Student Retention: What Next?"; and Alexander Astin, What Matters in College: Four Critical Years Revisited (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., 1993).

- Ken Blanchard, foreword to Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work & in Life One Conversation at a Time, Susan Scott (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2004), p. xiii.

- Janice Orrell, "Feedback on Learning Achievement: Rhetoric and Reality," Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 11, no. 4 (October 2006), pp. 441–456; Jared A. Chase and Ramona Houmanfar, "The Differential Effects of Elaborate Feedback and Basic Feedback on Student Performance in a Modified, Personalized System of Instruction Course," Journal of Behavioral Education, vol. 18, no. 3 (2009), pp. 245–265; Steve Prowse, Neil Duncan, Julie Hughes, and Deirdre Burke, "'…do that and I'll raise your grade': Innovative Module Design and Recursive Feedback," Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 12, no.4 (August 2007), pp. 437–445; and Mantz Yorke, "Formative Assessment in Higher Education: Moves Towards Theory and the Enhancement of Pedagogic Practice," Higher Education, vol. 45, no. 4 (2003), pp. 477–501.

- Tinto, "Research and Practice of Student Retention: What Next?"; Astin, What Matters in College; and Thomas Nelson Laird, Daniel Chen, and George Kuh, "Classroom Practices at Institutions with Higher-Than-Expected Persistence Rates: What Student Engagement Data Tell Us," New Directions for Teaching and Learning, vol. 2008, no.115 (2008), pp. 85–99.

- June C. Chang, "Faculty-Student Interaction at the Community College: A Focus on Students of Color," Research in Higher Education, vol. 46, no. 7 (2005), pp. 769–802, see p. 770.

- Chase and Houmanfar, "The Differential Effects of Elaborate Feedback and Basic Feedback on Student Performance"; and Laird, Chen, and Kuh, "Classroom Practices."

- Laird, Chen, and Kuh, "Classroom Practices."

- Data is from unpublished GPS System Reports for the 2009–2010 pilot.

© 2010 Mikhael Star and Lanita Collette. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.