Key Takeaways

- To remain fresh and relevant, online courses need to be continually revised and improved.

- Considerations of relevant laws and institutional policies should be a core focus of every curriculum redesign.

- Redesigning an online curriculum presents rich opportunities to integrate the latest thinking in given disciplines and to incorporate new methodologies for teaching and learning.

- New, emerging, and evolving technologies can greatly enhance work to update the curriculum of an online course.

A well-designed curriculum for online learning nurtures both student learning and student retention. While ideally value will be designed into an online curriculum from the start, the reality is that, across the spectrum of e-learning, there is a wide range of quality. Consequently, virtually every online course can benefit from periodic curricular updates.

Once online courses are developed and implemented, however, their curriculum might not be changed or updated for some time, if ever. When it does take place, curricular redesign tends to focus on particulars rather than the big picture. Rarely do we step back to fundamentally assess the raison d'etre for a given curriculum — to examine the essential cultural factors that undergird that curriculum and the purposes for which it was created.1 Analyses at that level have great potential to enrich a curriculum. In addition, curricular updates can introduce important new content, and may also introduce pedagogical enhancements that can improve the quality of e-learning.

In this context, this article presents ideas for an approach based in the principles of instructional design to updating the curriculum for online courses. Tools from that realm — including establishing processes for effective online learning, templating digital learning objects and modules for quality, defining clear work flows and decision junctures, adhering to standards of legality and ethics, and applying wise leadership and project management—offer a powerful approach to the development and refinement of quality curricula.

A Four-Fold Approach for Updating an Online Curriculum

A variety of factors can impede or preclude substantive updates in course content, including a lack of dedicated resources (budget, time, expertise); a lack of political will at the administrative level; inertia on the part of those who first developed the curriculum; and a protectionist attitude toward the existing course on the part of the course developers.

On the other hand, many forces can stimulate a curricular update, including the availability of external or internal grant funds, a push from administrators for higher course quality, an impending visit by an accreditation team, or the emergence of the need for a new degree or program that builds on the substructure inherent in existing courses.

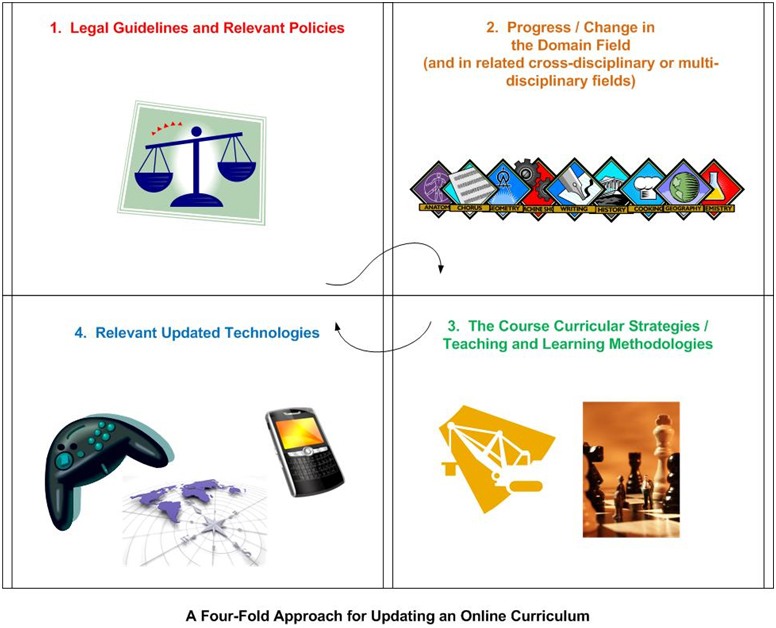

Once the decision to revise a curriculum is made, faculty and subject matter experts need to ask themselves four central questions:

- Have legal guidelines and relevant policies that might affect the course revision changed?

- What progress or change in the domain field might inform the course revision?

- What updates in teaching and learning methodologies might be relevant?

- What updates in relevant technologies could improve the course?

Coupled with these primary considerations should be an assessment of whether the individual interested in revising the course has the time and skills to do so effectively, and whether there is adequate institutional support for making the right changes to the curriculum.

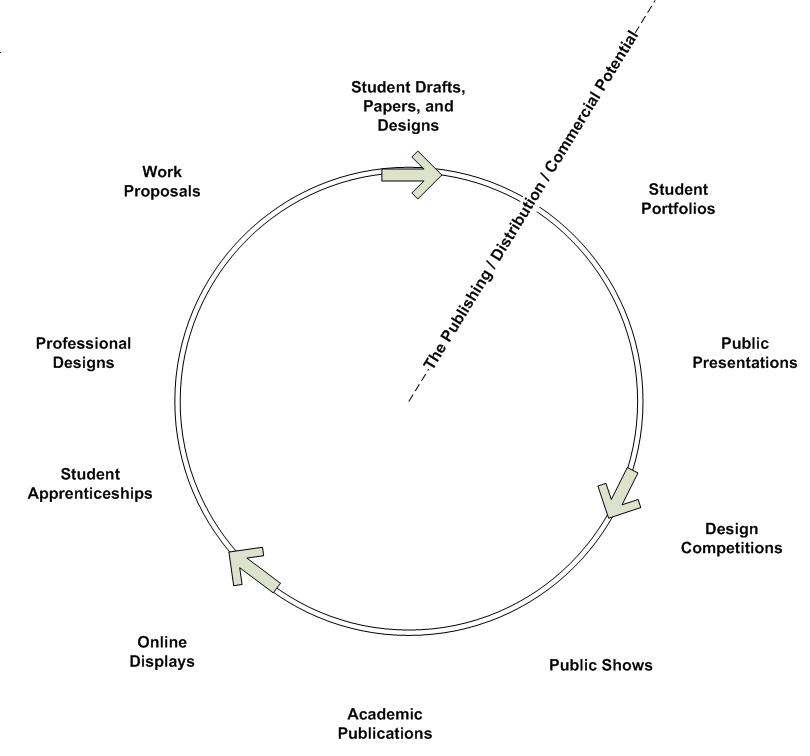

While different workplace contexts might emphasize these factors differently, and while many may include additional areas for update, answers to these questions are likely to have the greatest impacts on learning and the fundamental quality of the curriculum. Figure 1 shows this conceptualization.

Figure 1. A Four-Fold Approach for Updating an Online Curriculum

Why are these four questions important? An online learning experience that adheres to legal principles will uphold the reputation of the university and protect the rights of students. An online course curriculum that reflects the instructor's ability to stay current with research and developments in a particular discipline, perhaps in tandem with relevant interdisciplinary knowledge, will enhance learning by ensuring that students have the most current and relevant information. Applying the latest pedagogical methods can enhance the online learning experience. Targeting curriculum for different learning needs — including different developmental phases, different primary languages, and different learning contexts (cultural, geographical, social, political, technological, and domain field) — can enhance both individual and group learning experiences. The use of the latest relevant technologies for lecture capture, synchronous interactivity, simulations, student interactivity and intercommunications, student group work, research, design, and other learning activities can all improve the learner experience.

The draft checklist for updating an online curriculum that accompanies this article expands on the four questions/areas. Other readily available guidelines, such as the Quality Matters rubric, also provide valuable reality checks that can help inform a curricular redesign effort.

Updated Legal Guidelines and Relevant Policies

Curriculum revision requires careful attention to legal requirements and relevant institutional policies. Faculty adherence to the law can help keep legal liabilities for both the institution and the respective faculty member in check.

The legal dimensions of curriculum redesign include three key areas:

- Ownership of intellectual property

- Accessibility of online learning

- Learner privacy rights

Intellectual Property Protections

Any use of copyrighted text, images, videos, audio, or other content in an online course brings Intellectual property considerations into play. Given that de facto copyright ownership pertains once creative content has been put into fixed form, virtually anything created during the past few generations is automatically given copyright protections (unless that material is explicitly released by contract). Fair use exemptions and the TEACH Act (and its implications for distance education) allow very narrow uses of some small parts of copyrighted materials. Faculty members have other pathways to content: They can create their own content; use content released to the public domain; access open-source (and royalty-free) resources; or use content released through various Creative Commons licenses. Another option, of course, is to do without. Apart from those legitimate avenues, course developers are sometimes tempted to take decidedly riskier and ill-advised routes, swiping content off the World Wide Web without checking the content's provenance, ownership, or rights protection. Worse yet, developers might bypass digital rights management (DRM) protections around certain works in order to build their online learning collection.

Students have intellectual property rights to much of the work that they create in an academic course — including partial rights to co-developed works created by a student team. Before student-created works are used for future courses, publications, or other similar applications, faculty members and administrators need to ensure that students officially release their rights for those purposes in writing.

Commercialization of a curriculum raises its own legal issues, which are often further complicated because commercialization of a curriculum often requires that it be changed substantively. An academic course becomes a commercial work once it is used as part of a profit-making venture, outside the bounds of the umbrella implicit in an institution's nonprofit status. Once a work goes commercial, academic exemptions to copyright no longer apply. That means that a massive retrofitting will be required. Any works used under fair use will have to be removed. Works used with the permissions of third-party content providers (often contingent on learners using particular purchased textbooks) will likely need to be removed. There may be contractual challenges with a faculty member who is taking a curriculum commercial if he or she was paid to create the work for an accredited nonprofit institution of higher education.

Another complication arises when student work is involved. Students in many academic, design, and research-based courses will originate new ideas, lines of research, and innovations that have research and development implications. Works created in classes may fall under "fair use" in terms of the materials used in the student papers, portfolios, designs, drawings, and multimedia — but those works cannot be used under "fair use" if students are using the works for out-of-classroom purposes.

Figure 2 shows how, at "five after," student work has already left the classroom and has potential commercial applications — thus often changing student rights to use particular copyrighted materials. Instructors need to help students understand the legal issues implicit in their work and keep within the law as constructive contributors in their respective fields.

Figure 2. The Life Cycle of Student Work

Accessibility of Online Learning

Yet another legal issue concerns online accessibility. In this context, this means the ability of people with a range of different types of abilities, including those with visual acuity, sound acuity, mobility, and symbolic processing challenges, to access an online course and curriculum. The fundamental concern is how well curricula are developed to accommodate such users.

Available technologies enable developers to include alt (alternative) text for imagery, as well as transcription and captioning for audios, narrated slideshows, videos, and simulations, and to build accessible learning objects. A wide range of guidelines describe how to build digital tables in a way that is machine-readable using text readers. Courses built with federal and state funds are often required to be fully accessible per Section 508 and other applicable accessibility standards.

In making work accessible, subject matter experts focus on making sure that the informational value of the images and other digital elements is equal for all users. The process also involves instructional design (how the online learning experience is conceptualized and created) and development/scripting work (how the digital materials are created) to ensure that the digital learning objects fully comply with accessibility requirements.

Learner Privacy Rights

A final concern focuses on the privacy rights of learners. Through the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), students have privacy rights that protect much of their non-directory types of information. Private academic, health, and other student information may not be publicly shared.

Because students have a right to their own image and voice, they need to sign releases before a class can be captured on video, audio, or even in still images. The releases must be specific about what the learners are releasing and must delimit how digital captures may be used (in future online courses as student work samples, in publicity materials, in a broadcast digital video-sharing site, or on a course-related CD or DVD).

To understand the nuances of handling property rights appropriately in a classroom situation, consider the case of a professor teaching a class on weather and flight. His educational resources include slideshows and images illustrating his lectures, with materials pulled from multiple online sources. To explore his options, see "Modeling Proper Handling of Intellectual Property."

Progress and Change in Domain Fields

Informed by a constant stream of new research and information, domain fields change constantly. This is especially noticeable in research institutions that emphasize applied and theoretical research. Here, instructors are valued not only for their support of learners but for their contributions of new learning through their own work, their collaborations with colleagues, and student research under their tutelage.

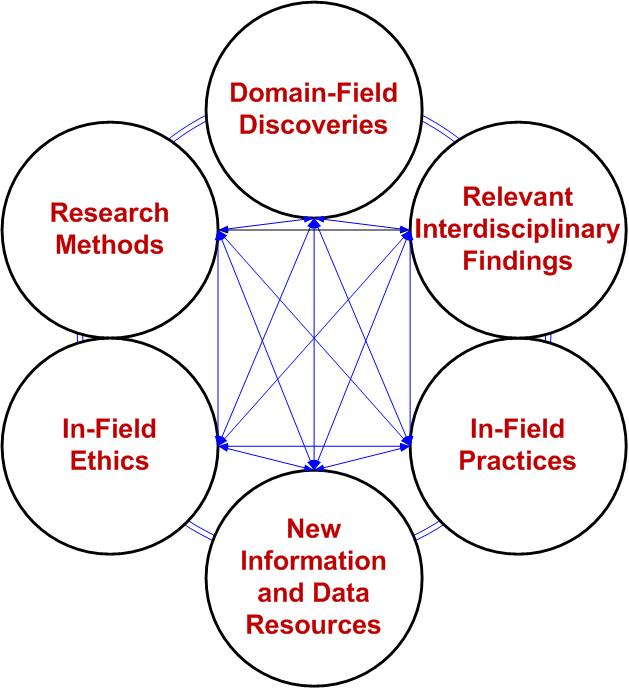

Domain fields often undergo true paradigm shifts, in which central concepts of the past are superseded by more nuanced understandings based on empirical research, quantitative and qualitative and mixed methods research, and high-level meta-analyses. Similarly, practices within domains can change, in both research and applications in the field. Different research frameworks may be applied. New informational data sets may become available, and more online resources may be released into the public domain.

New thinking could lead to changes in what is considered ethical in a particular field. The field's original set of ethics might have been derived from often competing interests, such as standards of the profession, a professional code of ethics, ethics of the community, personal codes of ethics, and individual professional codes.2

As the realities of a field evolve, they can have reverberating impacts. Changes in fields that are peripheral to a specific discipline often have impacts in a main area of study. Conversant knowledge in those peripheral fields will be necessary. Figure 3 shows these mixes of interrelationships.

Figure 3. The Interrelationships Between Domain-Field Elements That Affect a Curriculum

Given the reality of ongoing, often significant change in domain fields, it is imperative that faculty members stay apprised of the discoveries in their particular areas of expertise — certainly in the general interest of building new knowledge, but also in revising the curriculum for an online course.

To explore the complexity of working across disciplines in developing a course for geographically diverse learners, see "Collaborations Across Institutions and Disciplines" describing development of a public health course.

Updates in Teaching and Learning Methodologies

While some instructors might consider a course design complete once the course has been created, periodic or even regular updates can greatly enrich a course. This is certainly true of course content. Because they work within a componentized environment, course designers have considerable flexibility in reworking the modular curriculum and can switch content in and out at will. In addition, the flexibility of online course design enables faculty members to update teaching and learning methodologies.

E-learning Path or Trajectory

A core challenge in an online curriculum is to create a coherent e-learning path or trajectory, particularly for online learning deployed through multiple technologies or a learning/course management system. The more complex the content, the more diverse the learner skill sets, and the more divergent the preferred modes of learning, the harder it is to create a coherent sense of a singular path. Related learning content needs to be clearly labeled with consistent semantics, and these ought to be co-located in the same area in the online classroom.

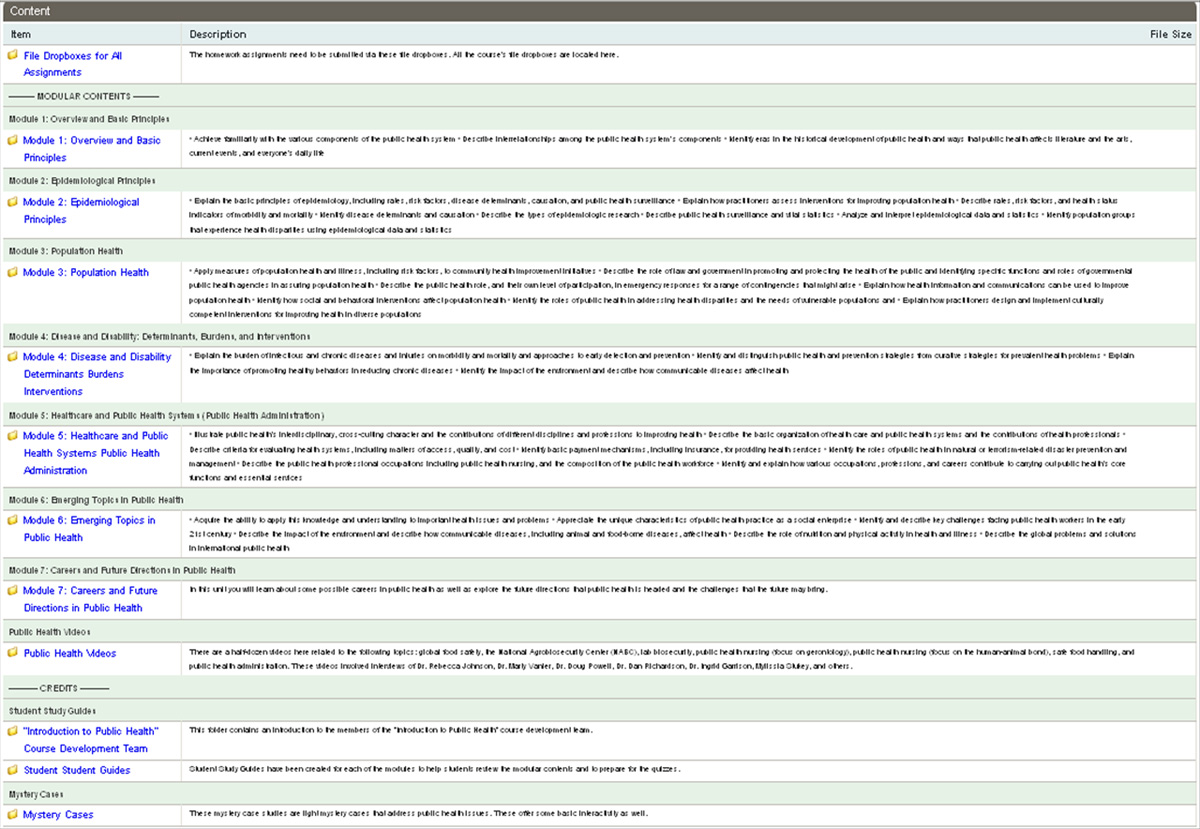

A course trajectory may be built on an informational structure that shows a clear progression of learning and ensures that learners have the information they need at a particular time. A trajectory helps learners get a sense of where they are in the curriculum, where they're going, and where they've been, at any time in a course. A newer type of learning path involves a story-centered curriculum, which tells a story with critical dramatic learning points along the way. To enrich the learning experience, "digital storytelling" involves the creation of narratives and shared experiences using multimedia.3 Figure 4 outlines one approach to a course trajectory, a course folder structure from the Introduction to Public Health course. The figure shows the overall course trajectory in a developmental and modular structure.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Top-level Folder Structure of Introduction to Public Health

A course retrofit should include an analysis of the learner experience as well as a review of the content segment by segment. The sequentiality of the learning needs to be clear. Segues between modules, courses (in a degree program), or sequences add coherence for learners, connecting students more directly with the content and enriching learning. The learning sequence needs to make developmental sense: Foundational knowledge should be addressed first, followed by discussions of more complex content.

Typical sequences involve an early social "icebreaker" to help online learners connect with each other and with the instructor. Often an early assignment introduces the course and encourages learners to share their hypotheses of where the course might be headed. It can also reveal students' expectations about the course materials, enabling the instructor to address misperceptions. Other components might include a review of course standards and policies and the sharing of learning tips. The instructor might address his or her pedagogical strategies and course expectations. Successful early assignments help build online learner efficacy.

Many online courses also use a certain "glamour appeal" to attract learners. Courses might include such assignments as the creation of a faux history for a criminology class, role-playing global interrelationships for a political science course, preparation of a feast for a nutrition class, or creation of a simple digital game for a computer science course. Course attractions could also involve trips abroad, participation in professional conferences, fieldwork, and other inducements.

Focusing on Learner-Centered Curriculums and Experiences

A curriculum should be calibrated to the particular developmental levels of its students. Gaps in knowledge, skills, and or learner preparation — problems that occur with more frequency given today's high drop-out rates in high schools and college — need to be addressed with remedial work, support, and well-presented information. The course designer should clearly define the e-learning trajectory and pacing and properly design them for the particular levels of learners.

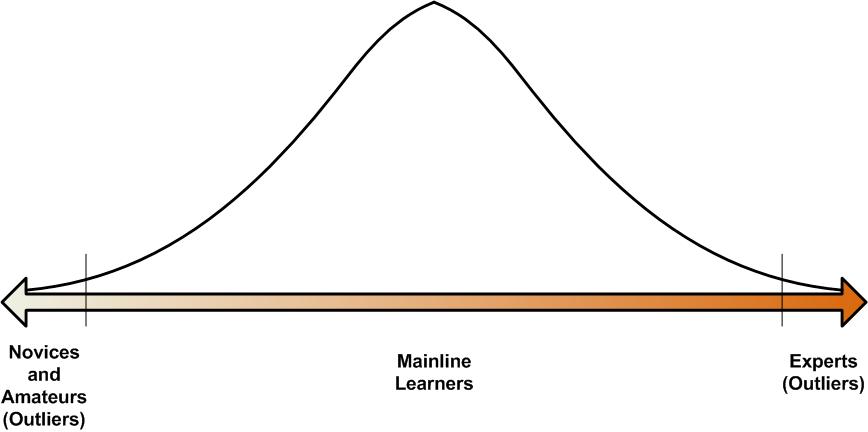

Also important is the human-facilitated capability of adjusting a curriculum to meet the unique needs of a range of online learners. One of the implications of "scaffolding" learning is to build structures that enable learners to achieve learning that they wouldn't otherwise. Scaffolding can effectively help a range of learners remain engaged. It can be used, for example, with student "outliers," such as the novice (a learner who is inexperienced and naïve but aims to become expert in a particular field) and the amateur (a naïve learner who seeks only a surface understanding of a particular field and does not aim for future expertise). The scaffolding concept can also effectively enhance learning for expert outliers at the other end of the bell curve of learners, perhaps through the study of more advanced research topics. Figure 5 shows the conceptualization of the minority outliers on a bell curve, with novices and amateurs at one end and expert outliers at the other.

Figure 5. Scaffolding Learning for the Outliers: Novices and Amateurs, and Experts

One recent trend in curriculum design has been toward a "contributing student pedagogy," in which learners contribute to each other's learning and value the contributions of peers. This approach has reformulated the instructor-learner power structure by emphasizing the importance of learner choices, attitudes, and voices. The contributing student pedagogy also focuses on building "increased content understanding, improved generic skills, increased motivation, increased satisfaction, increased confidence, (and) improved social skills" — all of which contribute to learner retention.4

Instructors might also design opt-in resources for students who seek assistance. Tutorial systems sometimes feature animated intelligent avatars to interact with learners. Some of these resources provide opt-in, context-sensitive help, such as directions for using a learning/course management system or a certain software program. For human-facilitated courses, instructors also make themselves more widely available to support student learning by providing information, access to resources, constructive critiques, and rich learning opportunities.

As online curriculums reach wider audiences, more retrofitting might be necessary to ensure that particular learning sequences are tailored to particular learners and the cultural environments in which the learning content will be used. Curriculums might need redesigns to be more inclusive, particularly of groups whose voices have not always been fully heard,5 even requiring translation of content into different languages. A curriculum might require tailoring content to a particular context, whether cultural, geographical, social, political, technological, or specific to a domain field. To accommodate a diversity of learners with different learning preferences and styles — such as kinesthetic/tactile, auditory/visual, logical/mathematical, musical/rhythmic, verbal/linguistic, visual/spatial, and interpersonal/intrapersonal — might require diversifying assessments to include a wider range of formative and summative measurements. Many assessments that are effective in the face-to-face classroom also work well in the online classroom.6

There are many ways to create value-added learning for online studies. Some faculty use case studies to enliven discussion and show how theories apply in real-world situations. Games, simulations, and immersive learning can contextualize the learning (to enhance "situated cognition"). The uses of role plays in these situations enable learners to empathize with certain roles and to view strategic interplays of various entities in a system. Games may evoke more positive emotions in learners toward the subject matter.7 Informational structures and ontologies help learners form mental models of dynamic interrelationships and systems.

In higher level courses, problem-based learning can be effective. The instructor can include examples that have no apparent solution, even for subject matter experts, or where the "answer" involves complex, open-ended designs with varying and competing degrees of appropriateness for the context (as, for example, in land-use proposals in the context of landscape architecture). Project-based learning can encourage students to engage in unwieldy projects, either alone, in pairs, or as part of multidisciplinary teams.

Some programs use undergraduate research as a means to increase student retention and help them bridge to graduate-level learning.8 Cumulative activities such as e-portfolio building support student reflection on their learning, provide a vehicle for students to receive feedback from experts, and enhance peer learning. Students may create rich works for digital gallery shows, or they might conduct research and write up their findings in integrative papers. Students can push the edges of the academic and outside worlds by engaging in professional or amateur competitions, apprenticeships, service learning, and work-study endeavors. Table 1 shows three main types of learning, from basic informational learning to learning acquired through applied skills and conceptual domain-level modeling and innovations.

Table 1. A Simple Conceptualization of Types of Higher Education Learning

| 1. Informational Learning This level of learning is the type conveyed in survey and introductory courses. Students learn by rote memorization and practice and study. This initial level of learning sets the groundwork of understandings in a field. | 2. Applied Skills This level of learning is often used in higher level courses. Hands-on practice may be done via simulations, digital wet labs, role plays, and virtual immersive spaces. Students may also apply skills in apprenticeships out in the community, in service learning (whether locally, domestically or abroad), fieldwork, and field research. | 3. Conceptual Domain-Level Modeling and Innovations This domain-level of mastery results in expert-level analysis and expert-level knowledge of interrelationships in a particular field. This suggests a powerful ability to analyze problems and troubleshoot them in a live situation. It also suggests the ability to conceptualize new research and to carry through that research to fruition and to contribute new knowledge to the field. |

| Conceptual Learning: principles, theories, values, and themes; the learning of abstractions (affective, cognitive) | Logical Analysis: the identification and locating of relevant information to the relevant issues; the proper application of logic to the relevant issues; the drawing of correct conclusions based on the given knowledge (affective, cognitive) | Synthesis of Complex Information: Systems (affective, cognitive) |

| Factual Learning: historical details, biographies of contributors to the field, empirical research findings, statistical analyses, research artifacts (cognitive) | Troubleshooting Problems: setting up problems/solutions; conducting research on projects (affective, cognitive) | Research and Discovery: The conceptualization and execution of rigorous research; the revelation and presentation of new information and knowledge about the field (affective, cognitive, behavioral) |

| Evaluative Learning: aesthetic approaches, analytical concepts and methods, logical analysis (cognitive) | Psychomotor Skills: troubleshooting and appropriate actions (affective, cognitive, behavioral) | Design: The application of complex information to a design challenge; the creation and execution of a new design (affective, cognitive, behavioral) |

| Affective Learning: attitudes, emotions (affective) | Social Learning: interactions with others; soft skills (affective, cognitive) | Innovation: The creation of new applications of a field (affective, cognitive, behavioral) |

The Social Interactivity Layer

As student-centered learning continues to supplant instructor-centered learning, many instructors are retrofitting their courses for more planned intercommunications, interactivity, and collaborations between learners.9 Various methods of student community-building in distance courses enhance a sense of interactivity and promote learner retention.10 The scaffolding of learner interactivity supports learner retention and may combat "feelings of isolation, lack of self-direction and management, and (an) eventual decrease in motivation levels."11 In this model, learners work on shared independent projects. Peer learners give feedback and support each other's learning. Students form professional networks and personal friendships.

Participation and interactions with learners in an online classroom help create a stronger telepresence, or sense of "being" in the classroom, on the part of the instructor. Researchers have found that such a presence enhances the learning experience but does not have a direct effect on "perceived learning, satisfaction, engagement, or the quality of their final course product."12 Other researchers have found that direct personal attention may relieve adult anxieties about school and increase learner retention.13

Some instructors plan synchronous events — with guest speakers, complex role plays in virtual worlds, and cross-institutional learning exchanges — to enhance the value of the learning. Others create blended experiences for learning, with students meeting in physical spaces for field trips and experiments. Encouraging interrelationships between learners helps improve student retention and degree completion rates. Students who take courses with peers often are more motivated and committed to continue in their learning.

The educational research literature includes many important findings about what is effective for online teaching and learning. Some fundamental works include Ruth Colvin Clark and Richard E. Mayer's E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning (2nd edition), and Clark Aldrich's Learning Online with Games, Simulations, and Virtual Worlds: Strategies for Online Learning and Learning by Doing: A Comprehensive Guide to Simulations, Computer Games, and Pedagogy in E-Learning and Other Educational Experiences.

A team built a virtual space in Second Life to demonstrate the adaptations possible to meet the needs of people with disabilities. To explore the options and limitations of virtual inclusiveness, see "Inclusiveness in a Virtual World."

Relevant Updated Technologies

Many distributed learning courses become dated essentially as soon as they launch. Courses can become dated by virtue of the authoring tools used to create their content, including text files, the slideshows, the audio, the imagery, and the video. Similarly, they can become dated by virtue of changes in their learning/course management system, web browser, media player, virtual world space, or related elements and layers of the technological dependencies required for online learning. This aging-out of content also occurs as a byproduct of the ongoing push to develop new technological and pedagogical methods. The speed of change will leave behind those who do not move with the technological current.

New generations of online learners have learned to expect regular rollouts of newer, better, and faster levels of technological expertise. What is innovative and new in a curriculum today becomes simply the baseline expectation of new generations of learners. Everyday exposure to sophisticated production values in multimedia applications creates expectations among students that online courses will have similar production values; anything less can draw negative responses about the course as a whole.

The availability of camcorders, digital cameras, scanners, microscope-mounted cameras, digital microphones, and desktop lecture-capture software enables virtually anyone to become a producer of digital content. Digital content can be edited at one's desktop through video editing, image editing, and sound editing software. These relatively new technologies enable students to represent ideas in different formats, which enhances their deep learning along both visual/spatial and auditory/verbal information channels.14 Material that originated in digital form can be readily deployed in online immersive sites or on different platforms. The scalability of some of these online experiences can help learning experiences feel more personal and intimate, particularly in larger sections of courses where direct one-on-one interaction with the instructor is rare.

The true total cost of ownership of online learning materials is high if one does an actual accounting that factors in all the costs associated with the countless elements that typically contribute to a curriculum, from information technologies staff and faculty to the costs of wired infrastructure, hardware, software, security, subscriptions to data repositories, maintenance of digital labs, funding for curriculum development and maintenance, and so on. The reality is that e-learning is predicated on layers of technological and human resources dependencies.

In terms of relevant technologies, most course or instructional designers need to consider two main elements, maintenance and value-added. Maintenance refers to a kind of digital preservation of online learning content; value-added refers to the enrichment of the online learning experience.

Maintenance means ensuring that digital content is preserved against obsolescence and the "slow fires" that degrade technological content. The informational value of learning materials must be preserved over time. The materials need to be accessible, and both deliverable by a university and receivable by its learners. Digital rights must be preserved, as must metadata about the objects. The content has to be portable between technological systems. The integrity of digital content must be maintained in all its incarnations, no matter the platform used. Digital labs, simulations, and immersive experiences need to function as scripted.

By contrast, value-added technological updates involve the uses of high-tech resources to enhance learning experiences. Many forms of digital content, such as images, audio, videos, simulations, and games, have been rendered in digital form and made available through many technology structures, including digital repositories and libraries. They might include interviews, simulations, role plays, interactive spaces, photo collections, and other types of files. From the value perspective, the selection of instructional technologies depends on a robust assessment of learning needs.15

Technological advancements also affect the types of tools used for learning. Popular ones for information aggregation and sharing include wikis, web logs or blogs (including in-the-cloud solutions), 140-character long microblog entries, social networking sites (for identity management, socializing, real-time information-sharing, and co-learning), and content sharing sites (for videos and digital imagery). Course content now often needs to be deployable on mobile devices. Virtual worlds enable the creation of discovery learning spaces; they also enable live simulations with other human-embodied avatars for different social scenarios and digital dramaturgy. Haptic devices (in direct-manipulation animation) have been integrated with 3D virtual spaces for a more full-sensory experience. Other learning may occur in augmented physical spaces ("mixed reality"), with digital installations built for immersive experiences that take advantage of proprioception and muscle memory.

A grain science instructor had used a paper-bound book with samples of grain, which restricted use to relatively few students and required a great deal of labor to maintain. Conversion of the original to an e-book made the material more accessible to students, as explained in "A Grain Science E-Book."

To explore the additional issues involved in successful redesign of an online course curriculum, see "Further Considerations for Curricular Updates."

Conclusion

Updating an e-learning course, whether through modest tweaks or a total overhaul, can help make a course more competitive, memorable, and effective. This article suggests four main foci for online course updates and retrofitting:

- The course's adherence to legal guidelines and relevant policies

- The course's information quality and timeliness, and domain-based digital content

- The course's curricular strategies, and online teaching and learning methodologies

- Relevant updated technologies that might help refine the course

Changes do not have to be made all at once. In practice, they may occur in a piecemeal way. All changes should be implemented, though, within the limits of the documents authorizing the course and the authorizing environment. Locally, the limitations of political will, budget, time, and expertise will all have an effect. Given the breadth of the four areas, one faculty member will probably not be able to engage the issues of laws and policies, information quality, curricular strategies, and updated technologies; ideally, a healthy institution of higher education will have support offices that provide a range of course design support services to faculty along with subject matter experts, perhaps as part of ad hoc teams.

These four broad areas are not comprehensive listings for online course updating. At the macro level, changes may be made to the superstructures outside of a class to enhance its value by linking it to a sequence of learning or a powerful applied learning context (service learning or study abroad programs are good examples). Cross-cultural alliances between institutions can lead to richer learning. Courses could be linked to external repositories of digital resources, add-on functionalities (such as e-portfolios and galleries), and immersive worlds to add learning value. Learners may participate in professional online conferences and digital poster sessions. At the micro level, unique changes to a course — such as the inclusion of guest speakers with plenty of real-world experiences, multi-language accommodations, or the inclusion of original student work samples — would improve the learner experience. Each course redesign will have its own considerations and require tailoring to meet the specific situation.

Effective updating of course curriculums to support and engage learners will encourage their persistence in the course and ultimately in their program of study, promoting degree attainment. Vincent Tinto noted that there are five conditions16 for learner retention:

- Expectation

- Advice

- Support

- Involvement

- Learning

As Tinto wrote, "Learning has always been the key to student retention. Students who learn are students who stay."17 Learner successes in learning, course by course, are a critical building block to their persistence. Updating online curriculums — whether through tweaks or paradigm shifts — offers a key way to increase learner retention and success.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the anonymous peer reviewers who gave me plenty of constructive and insightful feedback to improve this work. Nancy Hays, EQ editor, has provided critical support. Thanks to the various principal investigators and professors with whom I worked on the various projects described here. Thanks to R. Max.

- Pamela Bolotin Joseph, Stephanie Luster Bravmann, Mark A. Windschitl, Edward R. Mikel, and Nancy Stewart Green, Cultures of Curriculum (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000).

- Joan Poliner Shapiro and Jacqueline A. Stefkovich, Ethical Leadership and Decision Making in Education: Applying Theoretical Perspectives to Complex Dilemmas (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001).

- Nalin Sharda, "Creating Innovative New Media Programs: Need, Challenges, and Development Framework," in Proceedings of the 2007 International Workshop on Educational Multimedia and Multimedia Education (EMME), held in Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany, 2007, pp. 77–86.

- John Hamer, Quintin Cutts, Jana Jackova, Andrew Luxton-Reilly, Robert McCartney, Helen Purchase, Charles Riedesel, Mara Saeli, Kate Sanders, and Judith Sheard, "Contributing Student Pedagogy," Inroads, vol. 40, no. 4, 194–212.

- Colleen A. Capper, Educational Administration in a Pluralistic Society (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993).

- Thomas A. Angelo and K. Patricia Cross, Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers, 2nd edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993).

- Christian Kittl and Otto Petrovic, "Pervasive Games for Education," a presentation at the Euro American Conference on Telematics and Information Systems, held in Aracaju, Brazil, 2008.

- Teresa Dahlberg, Tiffany Barnes, Audrey Rorrer, Eve Powell, and Lauren Cairco, "Improving Retention and Graduate Recruitment through Immersive Research Experiences for Undergraduates," in Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest Group in Computer Science Education (SIGCSE) Symposium, held inPortland, Oregon, 2008, pp. 466–470.

- Carla Payne, Information Technology and Constructivism in Higher Education: Progressive Learning Frameworks (Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference, 2010).

- Thierry Isckia and Charles Delalonde, "Student Communities in a Distance-Learning Environment," SIGGROUP Bulletin, vol. 24, no. 3 (2003), pp. 73–78.

- Stacey Ludwig-Hardman and Joanna C. Dunlap, "Learner Support Services for Online Students: Scaffolding for Success," The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 4, no. 1 (April 2003), p. 1.

- Alyssa Wise, Juyu Chang, Thomas Duffy, and Rodrigo del Valle, "The Effects of Teacher Social Presence on Student Satisfaction, Engagement, and Learning," in the Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Sciences, 2004, pp. 568–575.

- G. Smith and V. Bailey, Staying the Course, 1993, as cited in Sandra Kerka, "Adult Learner Retention Revisited," ERIC Digest No. 166, 1995, pp. 5–6.

- Diane F. Halpern and Milton D. Hakel, "Applying the Science of Learning to the University and Beyond: Teaching for Long-term Retention and Transfer," Change (July/August 2003), p. 39.

- Allison Rossett, "Needs Assessment," in Gary J. Anglin, ed., Instructional Technology: Past, Present, and Future, 2nd edition (Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 1995), pp. 183–196.

- Vincent Tinto, "Taking Student Retention Seriously," 1995, p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 3.

Further Considerations for Curricular Updates

Depending on organizational priorities, online course curricular updates may occur at various intervals. Some of these updates deal with issues of maintenance, while others derive from a desire to improve value-added learning. The following table differentiates between updates needed for every term, each academic year, as needed.

The Frequency of Online Course Element Updates

| 1. Adherence to Legal Guidelines and Relevant Policies | 2. The Information Quality, Timeliness, and Domain-based Digital Contents | 3. The Course Curriculum and Teaching and Learning Methodologies | 4. Relevant Updated Technologies | |

| Every Term

| Syllabus – guidelines and policies Scheduling Connections to relevant campus resources | New sample student assignments (with student releases) Correction of "dead links" to learning resources | Updated assignments (to head off plagiarism or academic dishonesty from prior terms) Curricular fixes during the course | Updated file types The portability and transferability of digital objects The usability of digital objects in various technological systems/socio-technological systems Integration of open-source resources Integration of virtual/immersive worlds (in alignment with new assignments) Anything that needs updates for functioning (staying ahead of technological obsolescence) |

| Every Academic Year

| Relevant new laws, state policies, and campus policies

| Third-party publisher-created contents E-books Published articles | The integration of relevant imagery into the curriculum The enriching of a curriculum through more customized assignments and more learner feedback and choices on the topics of study Improved student interactivity Improved instructor feedback loops | The integration of new technologies Remaking of some lecture captures Building usability into online data repositories and resources |

| As Needed

| Intellectual property corrections Accessibility retrofitting for machine readability, textual annotations, and other accommodations Media rights releases for video/audio/digital still image and other captures of student learning and activities Universal design retrofitting | SME guest speakers' presentations and resources

| Scaffolding for novices/amateurs and experts (with learning aids, games, opt-in help, and other elements) Value-added learning Extra credits Field trips Case studies Digital labs Research opportunities Student publications Student gallery shows Student e-portfolios | The add-on of tech-intensive learner experiences The uses of a richer array of tech-enabled research streams (as relevant)…such as with remote sensing, geographical information systems, digital repositories and referatories (like the Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching from MERLOT), and so on The addition of metadata to learning objects for findability and accurate labeling |

In addition to the many dimensions of curriculum redesign already discussed, several other considerations merit brief mention.

Instructor Inheritance of an Online Curriculum

Many online courses, modules, and digital learning objects are not built with instructor inheritance in mind. "Inheritance" refers to the acceptance of the curriculum by other faculty who will teach to the established and formal standards of that course, module, or learning object. Instructor manuals rarely accompany such courses. The assumption is that experts in the field will be able to intuit the curriculum creator's intentions through the course's syllabus, assignments, assessments, lectures, and other elements.

The creation of a basic packet for inheriting instructors, with insider tips about instructional methods, strategies, and resources, ensures the smoother transition of a course from one professor to another. Also, building a curriculum with an eye toward eventual inheritance can reduce the idiosyncratic elements in course materials.

Beyond a simple instruction packet, full documentation of the entire course is also a necessary component of optimal curriculum design. Those who inherit a course will have a clearer range of choices and motion if they know the provenance of all the contents, if the digital materials are properly annotated and reasonably accessible, and if the original pedagogical plans are shared. The better an online course build is documented, the more easily it is preserved into the future. Also, the easier it is to update.

The documentation may include legal documents, such as contracts, grants, formal letters of support, memorandums of agreement or understanding, media rights releases, copyright releases, and permissions. It might also include raw files from photo shoots, videography sessions, audio sessions, machinima captures, and lecture captures. Because raw digital data captures tend to be the "least lossy," they must be protected for potential later use and possible editing into different file types and digital learning objects.

Adult Learner Retention

Research suggests that adult learners prefer practical learning that benefits their work lives. They need to have a clear sense about why they need to learn a particular thing. They need grounded learning that taps into lived experiences1 and are motivated by the usefulness of information and skills.2 These factors underscore the need for measureable and clear learning objectives and also suggest attributes that should be part of any course that will have adults as students. Instructors and course designers can enhance the online learner experience and make it more real and engaging through applications of rich, multimodal, multimedia, and full-sensory (visual and sound) immersive learning.

While learners base their decisions to continue in or drop out of a course on a range of reasons, only some of which instructors can influence, instructors do play an important role in helping learners, including adult students, acclimate to an online classroom. Instructors help connect learners to the campus, which can improve retention.3 They play a critical role in connecting learners to resources on campus. They set a professional and respectful tone by adhering to applicable laws and policies. They provide academic advisement. They have a major responsibility to create a rewarding learning experience that actualizes learner skills and knowledge. Instructors should identify at-risk learners (based on their communications and their submitted work) and provide tailored support for their learning.

Continuous Information Streams

Faculty in online courses benefit from information streams with learners and other stakeholders. One feedback loop involves learner participation in the online course. Instructors who maintain a course revision journal to capture the suggestions can apply these ideas to new designs, or they can integrate them immediately in the master course. Another strategy is to create formal and informal (back-end) channels for learner feedback.

Formal channels usually involve learner surveys that are part of student satisfaction feedback. Instructors sometimes solicit informal feedback from learners at the end of the term. Students will often communicate directly with instructors and offer ideas via e-mails and telephone calls, all information-rich ways to capture suggestions.

For shared, inherited courses that a group of instructors teach, the faculty may share their notes about lessons learned from their hands-on use of the curriculum and the experiences they had while teaching the course. Responsiveness to learner feedback both during and after the course may ease student frustrations, both by addressing their challenges and concerns and by respecting their voices.

Back-end data mining in the learning/course management system can also be highly instructive. For example, the system may capture patterns of when students participate in class. The system might also note which files learners access and what class-related message boards and activities they like the best, data that can spark ideas for enhanced student participation. As one practical example, data that show that students are hard-pressed to submit work in particular times of a learning term can help the professor schedule heavier work at a different time.

- Daniel C. Edelson and Diana M. Joseph, "The Interest-Driven Learning Design Framework: Motivating Learning through Usefulness," in the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Sciences, held in Santa Monica, California, 2004, pp. 166–173.

- Arthur M. Cohen and Florence B. Brawer, The American Community College, 4th edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 2003), p. 63.

- William A. Kaplin and Barbara A. Lee, The Law of Higher Education: A Comprehensive Guide to Legal Implications of Administrative Decision Making, 3rd edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995), p. 113.