Key Takeaways

- Traditionally, space planning has excluded the key stakeholders — instructors and students — until the very end of the sequential design process.

- A multidisciplinary, collaborative process that involves users from the beginning stages achieves pedagogical goals in addition to space-planning and technology goals.

- A classroom redesign at Ryerson University incorporated technology and pedagogy during planning to create a classroom that engages instructors and students alike.

Campus planners traditionally have guided the planning and building of learning spaces in the university. Historically, they have not invited the stakeholders (users) of the space — teachers and students — to participate in the planning process.

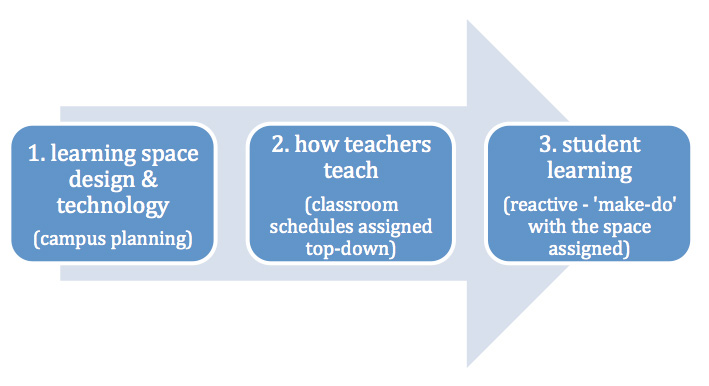

Planning typically has been a sequential and “dis-integrated” process involving planners, architects, and lastly teachers and students (see Figure 1). The outcome does not necessarily support teaching and learning. For example, a classroom may be equipped with a high-end computer, projector, document camera, and writing tablet and be set up in tiered rows with fixed desks, having limited provision for the professor to move among the students. This classroom succeeds in terms of the numbers of students it can accommodate and the technology it contains, but it fails when assessed from a pedagogical perspective.

Figure 1. Space Planning as a Sequential Process

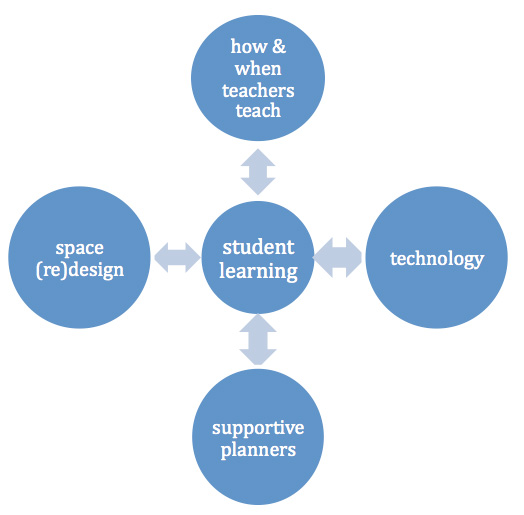

To create the conditions for truly engaged students and teachers, we must transform the campus learning-space planning process to include collaboration and participation by stakeholders. Creating a learning space that engages faculty and students and puts student learning at the center is an integrated, interconnected, mutually influential, and complex process. The issues related to pedagogy must be voiced, heard, and considered during planning. We believe that satisfaction increases when users of the classroom and study spaces on campuses are included in the process of designing and redesigning these spaces. The process identified in Figure 2 is a multidirectional, continuous process where each element informs the others. Involving teachers and students in the space-planning process can positively impact the teaching and learning experience they have in the classroom.

Figure 2. Space Planning as a Multidirectional Process

Many studies and best practices in learning space design recommend using technology to enhance student engagement. How the Internet generation, or digital native generation, uses technologies in their learning has been widely explored (see Further Reading). The challenge involves answering the following questions:

- How do we translate these findings into the design and planning of a learning space?

- Does this mean that we ought to install the latest gadget in every classroom?

- Will the high-end technology give students a better learning experience?

With student learning and engagement at the center of the planning process, the question of whether or not to install technology in the classroom will be answered appropriately. How, then, can an institution develop such an inclusive learning-space planning process?

Classroom Redesign at Ryerson University

Ryerson University in Toronto recently completed the redesign of an existing classroom. (Figure 3 shows the classroom before redesign.) Over a two-year period (2006–2008), an interdisciplinary committee1 guided each element while redesigning this learning space. Before 2006, the committee had focused on the integration of technology into learning spaces, but once technology had been added to most classrooms on campus, the committee broadened its mandate to include recommendations on how the design of the physical classroom learning space could support teaching and learning.

Figure 3. Ryerson Classroom Before Redesign

The room selected for the space-planning project was intended as a general-purpose classroom, so the redesign kept maximum flexibility in mind for the diverse mix of courses that would be taught in the space. The room was launched in fall 2008, and research into the perspectives of students and faculty using this classroom began soon after.

Figures 4 and 5 show the redesigned classroom with flexible table arrangements and embedded technology.

Figure 4. Redesigned General-Purpose Classroom

Figure 5. Redesigned Classroom in Use

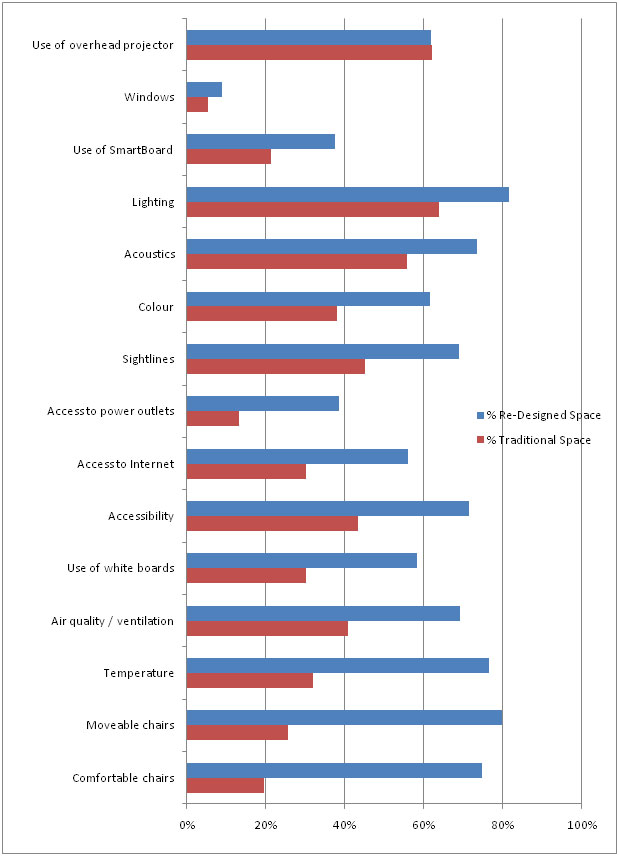

Figures 6, 7, and 8 show initial results from research into use of the redesigned classroom. Figure 6 shows student satisfaction with the redesigned space compared to the traditional space. Use of the overhead projector was about the same for both, but satisfaction with the chairs, accessibility, temperature, and ventilation all rose significantly in the redesigned classroom, as did access to power outlets. Satisfaction with use of the SmartBoard increased by more than two thirds.

Figure 6. Student Satisfaction with the Redesigned Space

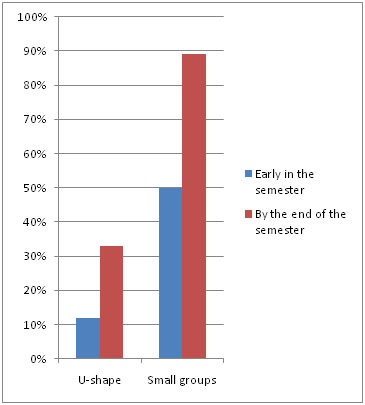

Figure 7 shows faculty use of the redesigned space in a U-shape or for small groups early in the semester versus by the end of the semester. Use of the space for small group work increased from 50 percent to nearly 90 percent over the semester.

Figure 7. Faculty Organization of the Redesigned Classroom

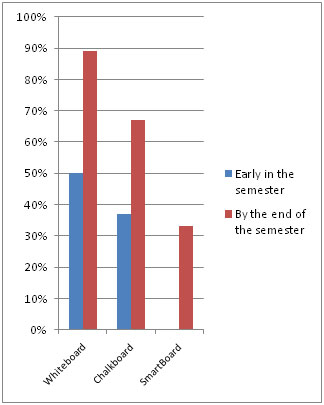

Figure 8 shows faculty use of technology in the redesigned classroom early in the semester and by the end of the semester, specifically the whiteboards, chalkboards, and SmartBoard. Note that no faculty used the SmartBoard early in the semester, probably because of initial unfamiliarity with the technology. Use of the whiteboards and chalkboards rose substantially over the course of the semester.

Figure 8. Faculty Use of Technology in the Redesigned Classroom

Redesign Recommendations

In this particular project, however, the committee believed that learning space design had to come clearly into focus, recommending that the university turn its attention to how learning spaces could support student learning. Shifting its focus from the physical requirements of a classroom space to identifying what elements of a space could support teaching practices and student learning was the context for the following recommendations for future learning space design at Ryerson:

- Multidisciplinary/collaborative approach: The complexity of teaching practices, including understanding how students learn best, requires a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach. Ensuring the support of best teaching practices necessitates the combined expertise of learning strategists, instructional designers, media specialists, and faculty disciplinary expertise (writing, information literacy, etc).

- Needs assessments: It is important to assess the professional development needs of those engaged in teaching and learning. Evaluating the learning needs of faculty and students with respect to the use of technologies in support of best teaching and learning practices should be a first priority.

- Learning opportunities: For teaching to remain effective and responsive to diverse students’ learning needs, faculty require opportunities to learn, to be guided in how best to design and implement their courses, and to practice (particularly using new technologies).

- Networking: To remain current with respect to best practices in teaching and learning in higher education, it is important that faculty and others engaged in learning space design have opportunities to collaborate and network with each other and with other universities and attend conferences that support the multidisciplinary and evolving nature of teaching practice.

- Research and evaluation: Learning space design needs to be informed by the growing body of literature and research in this area. This knowledge in turn must be integrated with pedagogical research and evidence in support of best teaching and learning practices.

We strongly believe that including building planners, technology planners, teachers, and students in an integrated, interconnected, mutually influential planning process for learning space design will result in more fully engaged teachers and learners. The initial results of Ryerson’s classroom redesign bear out this conclusion.

Further Reading

- Carini, Robert M., George D. Kuh, and Stephen P. Klein, “Student Engagement and Student Learning: Testing the Linkages,” Research in Higher Education, vol. 47, no. 1 (February 2006), pp. 1–32

- Coates, Hamish, “The Value of Student Engagement for Higher Education Quality Assurance,” Quality in Higher Education, vol. 11, no. 1 (April 2005), pp. 25–36

- Dunbar, Brian, “Green Building: For a Sound, Sustainable Future,” Institute for the Built Environment, CSU Department of Construction Management, 2007 presentation at a Poudre School District LEEDS training session

- Fielding, Randall, “Learning, Lighting and Color: Lighting Design for Schools and Universities in the 21st Century,” DesignShare.com, 2006

- HermanMiller, “Paradigm Shift — How Higher Education Is Improving Learning,” Continuing Education Unit, 2006

- Hunley, Sawyer, and Molly Schaller, Chapter 13, “Assessing Learning Spaces,” in Learning Spaces, Diana G. Oblinger and James L. Oblinger, eds. (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, October 2006)

- Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land Grant Universities, Third Report, “Returning to Our Roots: The Engaged Institution,” National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges, 1999

- Kuh, George, “Assessing What Really Matters to Student Learning: Inside the National Survey of Student Engagement,” Change, vol. 33, no. 3 (May/June 2001), pp. 10–17, 66

- Lilyblade, Annie, “An Assessment of Green Design in an Existing Higher Education Classroom: A Case Study,” Colorado State University, 2005; available on the National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities (NCEF) website

- Moore, Anne H., Shelli B. Fowler, and C. Edward Watson, “Active Learning and Technology: Designing Change for Faculty, Students, and Institutions,” EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 42, no. 5 (September/October 2007), pp. 42–61

- Nuhfer, Edward B., “Some Aspects of an Ideal Classroom: Color, Carpet, Light and Furniture,” California State University of the Channel Islands

- Oblinger, Diana G., and James L. Oblinger, eds., Learning Spaces(Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2006)

- Wolff, Susan J., “Design Features for Project-Based Learning,” 2002

- The disciplines represented on the design committee included the following offices and units: Vice Provost Faculty Affairs, Learning & Teaching Office, Campus Planning, Communication and Computing Services, Digital Media Projects Office, Library, University Planning, and Student Services. Also participating were students and faculty from the following schools and departments: Engineering & Applied Science, Professional Communication, Interior Design, Business Management, Architectural Science.

© Judy Britnell, Restiani Andriati, and Leslie Wilson. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 license.