Key Takeaways

- Learning takes place in a social context, and encouraging student-student and student-faculty contact and interaction gets at the heart of student engagement in online-education settings.

- Because of their fundamental reliance on social participation and contribution, Web 2.0 tools, specifically social-networking tools, have great potential for enhancing the social context in support of learning, especially in online education.

- Twitter used as an instructional tool can add value to online and face-to-face university courses that far outweighs its potential drawbacks.

"We've GOT to make noises in greater amounts!

So, open your mouth, lad! For every voice counts!"—From Dr. Seuss, Horton Hears a Who

Not long ago, we participated in EDUCAUSE 2009 in Denver. Because we were delivering a presentation on instructional uses of Twitter,1 our ears and eyes were wide open for other presentations mentioning social networking in general and Twitter specifically. And did we get an ear- and eye-full! It seemed like everyone was talking about Twitter — mostly positively, with a few pointed criticisms of the perceived obsession people have with the tool. At a lively "debate" ("debate" because ultimately both debaters were fairly pro-Twitter), the negative commentary focused on three things: Twitter takes too much time, the content is of questionable value, and it promotes social (or, anti-social) myopic-ness. We do not disagree, but instead have found, as many have,2 that Twitter's potential as a powerful instructional tool outweighs these negative factors. In this article we share some of the insights gained using Twitter as an instructional tool and explain why we think Twitter, despite its drawbacks (and really the drawbacks of social networking in general), can add value to online and face-to-face university courses.

The Challenge of Student Engagement

Our path to Twitter as an instructional tool was pretty straightforward. We teach online university-level courses in the field of instructional design and technology and constantly look for ways to enhance students' experience in the online-education setting. We are concerned with student engagement, including how to overcome the transactional distance that exists in online courses.3 Our students are nontraditional: working professionals typically either in K-12 education, higher education, or corporate training spaces, or changing careers. They reside all over the world and have full personal and professional lives. Conditions around them are rife with distractions, making student engagement even more challenging — and even more elusive — than in conventional instructional settings with a traditional student population.

Although there are many definitions of student engagement, we see it as the time and energy students devote to educationally purposeful activities and the extent to which the university encourages students to participate in activities that lead to their academic success.4 Engaged students are more likely to take initiative, exert effort, and persevere during learning activities. In addition, when students are engaged in learning, there is increased potential that they will be interested, curious, optimistic, and enthusiastic5 — all positive attributes of a healthy, productive learning environment.

Arthur Chickering and Zelda Gamson6 provided a framework for student engagement based on 50 years of research on educational effectiveness. Their framework includes a list of seven "good practice" principles that have guided student-engagement practice and research for the last 20-plus years:

- Encourage student-faculty contact

- Encourage cooperation among students

- Encourage active learning

- Give prompt feedback

- Emphasize time on task

- Communicate high expectations

- Respect diverse talents and ways of learning

This framework is, in part, the foundation of a well-established tool for systematically measuring student engagement: the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). The NSSE survey measures educational effectiveness based on five benchmarks of student engagement7:

- Academic challenge

- Student interactions with faculty

- Active and collaborative learning

- Enriching educational experiences

- Supportive campus environment

For nontraditional students like ours, the most influential academic experiences are those tied to course-related learning and their relationships with faculty and other students.8 This holds true for nontraditional students in online programs as well. In 1996, Chickering and Stephen Erhmann applied the original Chickering and Gamson framework to online education. They believed that, if the power and affordances of online education (and the technologies and tools used to deliver online learning opportunities) were to be realized, online educators had to adhere to the original good-practice principles.9 Still, at the top of their list (as well as prominently featured as an NSSE benchmark), is the idea that good practice encourages contact between students and faculty. Implied by Chickering and Erhmann's thesis is that knowing one's instructors well has a positive impact on learning, which may in turn help with retention and successfully accomplishing the goals of the course and program.10 Encouraging student-faculty contact and interaction thus gets at the heart of student engagement in online-education settings.

In online education, social presence is directly related to faculty-student and student-student contact and interaction, as well as the development of a culture of caring and trust needed for an effective online learning community.11 Specifically, social presence refers to the sense of another person as being "there" and being "real."12 It is "the ability of participants in a community of inquiry [a community of learners] to project themselves socially and emotionally, as 'real' people (i.e., their full personality), through the medium of communication being used."13 If social presence in an online course is strong, then students recognize their course colleagues and instructor as being there and being real. Often, online students' and faculty's sense of social presence is negatively affected by their transactional distance: the space and/or time separation between students and faculty that creates a psychological and communication space where potential misunderstanding can thrive.14 It is further exacerbated by the typical reliance on asynchronous, written communication, such as that delivered via threaded discussion forums in learning management systems (LMSs). Asynchronous, written communication lacks the immediacy needed to reduce personal risk and increase acceptance, which are important objectives when trying to establish a supportive and secure learning environment.15 Without a high level of social presence, students can feel isolated and disengaged because of a lack of communication intimacy and immediacy.16

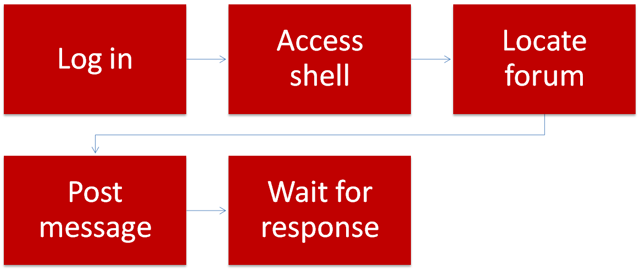

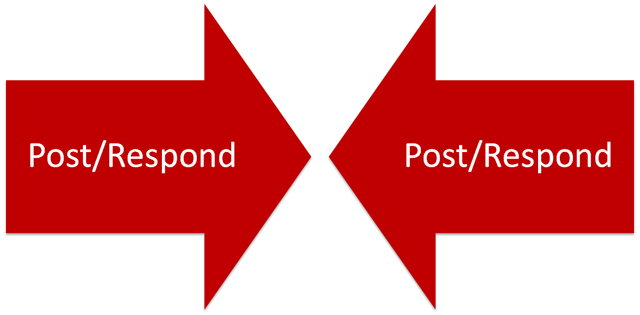

Web 2.0 tools have been a godsend in supporting our student-engagement efforts to achieve enhanced social presence in our online courses.17 We were looking for a more intimate and immediate form of communication, striving to involve students to such an extent in the joy of learning with us and with each other that they would become immersed in the online learning experience.18 Because of our years teaching within an LMS, we realized that we could not achieve a natural communication flow with students only using the tedious, multi-step process required. The typical LMS requires logging in, getting into the specific course's shell, entering the specific discussion forum, posting a question ... and then staying connected to the LMS while waiting for someone to respond — or giving up and moving on to other work, thoughts, and issues. (See Figure 1.) We wanted a tool that would enable us to establish an ongoing sense of being present at the current moment and able to receive and respond to students immediately, forming a real-time online dialogue and forum for sharing.19 By enabling us to connect and work with our students outside of the LMS, Web 2.0 tools — specifically social-networking tools — allow us to establish natural, free-flowing, just-in-time contact with students, and them with us. (See Figure 2.) The Web 2.0 tool that has helped us achieve this objective more than any other is Twitter. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 1. LMS-Driven Communication with Online Students

Figure 2. Desired Pathway of Communication with Online Students

Figure 3. Twitter and Desired Communication with Online Students

What Is So Special About Twitter?

Learning takes place in a social context. Higher cognitive processes originate from social interactions,20 with knowledge acquisition "firmly embedded in the social and emotional context in which learning takes place."21 Conversation, collaboration, and establishing a community of learners is critical to the teaching and learning process.22 Because of their fundamental reliance on social participation and contribution, Web 2.0 tools, specifically social-networking tools, have great potential for enhancing the social context in support of learning, especially in online-education settings.23

For those new to Twitter, it is a freely accessible, multiplatform, Web 2.0 tool — part social networking and part microblogging.24 Twitter's website describes Twitter as "a service for friends, family, and co-workers to communicate and stay connected through the exchange of quick, frequent answers to one simple question: What are you doing?" (Note, Twitter recently changed the question to "What's happening?") The video created by our colleagues at CU Online quickly describes what Twitter is and how people use it.

Currently, Twitter reports more than 18 million participants, while Facebook has 350 million, MySpace has 125 million, Friendster has 110 million, and LinkedIn has 50 million. What, then, is so special about Twitter? Although small by comparison, Twitter has unique qualities that make it a good fit for online education. For example, people use Twitter for much more than updating their current status. In 140 characters or less, people share ideas and resources, ask and answer questions, and collaborate on problems of practice. Depending on whom you choose to follow (that is, communicate with) and who chooses to follow you, Twitter can be used effectively for professional and social networking because it can connect people with like interests.25 Educators, specifically, are using Twitter to establish and develop personal learning networks.26 According to Messner, "A PLN, or Personal Learning Network, is a group of like-minded professionals with whom you can exchange ideas, advice, and resources."27

Social media researchers like to differentiate between friendship-driven and interest-driven types of participation in social media and social-networking sites.28 This differentiation, in part, is due to structure and functionality. Twitter is a less bounded, more open networking tool that allows asymmetric relationships. Facebook is a more bounded community, requiring symmetric relationships.29 In Facebook, if you befriend someone, they have to befriend you back, with the only other option being to not have any connection at all. In Twitter you can follow someone who does not follow you; someone can follow you that you do not follow in return; you can follow someone who also follows you; or you can choose not to have or allow a connection between you and others.

There is no question that Twitter and Facebook attract both types of participation and have a number of similar qualities. As one of our students commented:

"Twitter has been a great way for me to check in with everyone who is using it. I found out how others were feeling about school, how life was treating them, how their jobs and families were doing. This is something much more intimate than mandatory weekly discussions..."

We have found, though, that Twitter attracts more interest-driven participation (at least in our field of instructional design and technology) compared to Facebook, which continues to be used more often for friendship-driven types of participation. Our students seem far more likely to use Facebook for personal networking with family and friends, and they prefer to keep their academic and professional networking separate from their personal. When using Twitter for instructional purposes, therefore, we are less likely to intrude on students' personal networking space.30

The main reason we selected Twitter over other social-networking options, however, is because of its rapid-response attribute, which allows people to receive immediate, instantaneous responses. As described by Steve Thorton:

[Twitter] seems to live somewhere between the worlds of email, instant messaging and blogging. Twitter encourages constant "linking out" to anywhere and, in that respect, is more analogous to a pure search engine; another way to find people and content all over the Net.31

This benefit is further extended by additional features:

- Users do not have to log in to Twitter to receive updates if using an RSS feed.

- Twitter provides an interactive, extensible messaging platform with open APIs.

- The read page is the same as the write page, which allows for a more seamless exchange.

- A number of other applications are available to make Twitter more useful, such as Twirl, TweetDeck, Twitterific, and Digsby.

Because of these features, Twitter was a viable option for us to establish free-flowing, just-in-time communication with our online students.

Recent reports suggest that only about five percent of faculty use microblogging as a part of instruction32 and that the majority of faculty do not use Twitter at all.33 Perhaps faculty resist using Twitter for instructional purposes because of the very concerns expressed during the EDUCAUSE Twitter debate. However, we have found a way of using Twitter with our students that minimizes these concerns, while supporting faculty-student connection and benefiting other instructional objectives.

Our Instructional Use of Twitter

We initially explored Twitter as an instructional tool to provide an informal, just-in-time way for our students to connect with each other and with us throughout the day. We invited students to participate in Twitter with us, explaining our goals (student-faculty connection and enhanced student engagement). We did not require their participation because we recognized that they might already be involved in social-networking activities and not want to take on more, or because of their concerns about privacy and their online footprints.

With Twitter, as with all social-networking tools, the value of the experience hinges on three things: (1) who you are connected to and with; (2) how frequently you participate; and (3) how conscientious you are about contributing value to the community. Therefore, to establish relevance and to make sure students got off to a good start, we took the following steps:

- We provided students with a list of professionals who are active, relevant contributors (in addition to our Twitter IDs and the IDs of other students in the course).

This narrows the network to those who can immediately contribute to students' learning and professional development and addresses colleagues' concern about time spent. People who are new to Twitter often express uncertainty about how to find the right people to follow. While users can search Twitter posts for like-minded people, there are no guarantees. The majority of Twitter accounts are abandoned during the first month,34 probably due in part to users' inability to find the "right" people to follow — that is, people who can contribute to their learning and professional development. By providing students with a list of people (who we personally have benefited from following), we hope to help them get off to a good start with Twitter. In our field of study, for example, we recommend following Garr Reynolds, Nancy Duarte, Scott McCloud, Will Richardson, George Siemens, and David Warlick, to name a few. We also suggest following relevant professional organizations (EDUCAUSE, Sloan-C), publications (Chronicle of Higher Education, Education Week, EDUCAUSE Review, Wired), and companies (Apple, VoiceThread, SlideShare, Inspiration).

- We shared examples of professionally appropriate ways to engage in and with the Twitter community.

People critize Twitter (and social networking in general) because they believe that it promotes social (or anti-social) myopic-ness. While we have seen many examples of this, we believe that there is nothing inherent in the technology that causes it. In fact, we find that through sharing and modeling what we believe to be appropriate ways to use and engage in the Twitter community, we can help our students avoid a myopic perspective.

- We encouraged students to share their knowledge, work, and discovered resources (blog posts, YouTube videos, Web 2.0 tools, etc.) with the Twitter community.

While we believe there is some value to the social chitchat that happens on Twitter — especially when trying to get to know others and establish one's social presence — we have found that much of the value people, especially educators, get out of Twitter is derived from the knowledge and resource sharing.35 We strive to get our students to not only consume but also to produce and contribute knowledge and resources to the larger community. We believe that through mixing social chitchat and resource sharing, our students and the Twitter community as a whole can establish value and relevance, addressing concerns shared by some colleagues about the value of Twitter.

- We allowed students to cite tweets in their course projects and papers (as an electronic source of information).

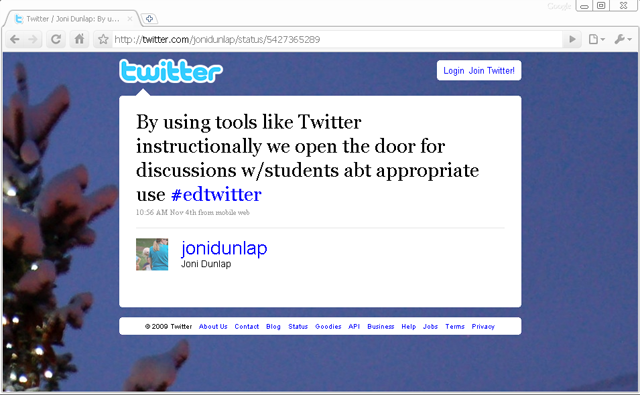

For us, tweets, while brief, are a valuable source of information. Therefore, students should be able to cite tweets in course projects and papers. Twitter supports students' ability to do this because each tweet has a unique and stable URL. (See Figure 4.) Therefore, we direct students to cite tweets as recommended by APA style. However, we recognize and strive to communicate to students that they should always support the claims they make by citing multiple and different types of resources, not relying only on the information they attain via social networking.

Figure 4. Example of Tweet with Corresponding URL

- We frequently contributed our own status updates, ideas, resources, and so on.

Finally, we believe it is imperative to contribute frequently to the Twitter community. By doing this we demonstrate to students that developing and maintaining a PLN is not simply an academic exercise but rather a lifelong learning skill.36 There is no question that active and frequent participation in the Twitter community takes time, as concerned colleagues have voiced. However, we believe that if Twitter participation is initiated by a learning need and subsequently driven by learning goals and objectives, then the activity is relevant and purposeful, and Twitter time is time well spent.

As one or our students commented after using Twitter for a course:

"I enjoyed twittering. It was fun to have a small group to get started with. If we hadn't started as a class I probably wouldn't have picked it up on my own. But, it is a fun way to connect. You are accessible via email and in the shell, but Twitter increases feelings of connectedness."

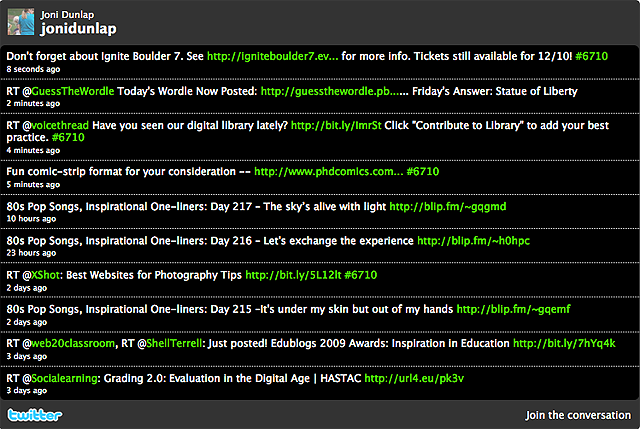

Like other social-networking tools, Twitter is affected by what Joshua Porter (an active blogger on the topic of social web design) refers to as the "opaque value" problem.37 Because social-networking tools are forums for personalized, socially focused conversations, the communities that spring from these tools are person/people-centered. As Porter explained, this person/people-centeredness results in the value of participation being opaque for anyone who is not participating. To address this problem, we made sure that students who chose not to participate (because the value of participation is opaque for them) had access to our tweets by incorporating an RSS feed-like Twitter widget in our LMS. (See Figure 5.) Many widgets like these can be found online, although we should note that this particular widget has limitations. As seen in the example in Figure 5, the widget only displays Joni's posts, not the back-and-forth exchanges between her and members of her network. Students might incorrectly assume that the interaction is one-sided and less than dynamic. Besides keeping students apprised of the resources we shared via Twitter, however, this widget allowed them to vicariously discover Twitter's value. Some students later chose to join us in Twitter because they had a better understanding of what they were getting into because its value was less opaque. Ultimately, we found that Twitter helped us achieve our student-engagement objective, but we also quickly discovered that students' Twitter participation led to other notable instructional outcomes.

Figure 5. Twitter Feed

Engaging with Professionals

Twitter engages students in a professional community of practice (CoP),38 connecting them to practitioners, experts, and colleagues. This helps enculturate them into the community,39 which becomes especially important for students in professional-preparation programs. Acting as practitioners and using the tools practitioners use to address authentic problems of the domain exposes students to the culture of expert practice.40 Through their participation in Twitter, students can engage in learning as a function of the activity, context, and culture of the CoP for their field.

Besides the networking potential as students build PLNs, they can receive immediate feedback to questions and ideas from practicing professionals in Twitter, which enhances their learning and enculturation into their professional CoP. Examples of the types of interactions our students had with professionals via Twitter include:

- A student had a question about a chapter she was reading on multimodal learning. She immediately tweeted her question and received three responses within 10 minutes — two responses from classmates, and one from her professor. This led to several subsequent posts, including comments from two practicing professionals.

- A student working on his final project was trying to embed music into a presentation. He was having trouble getting it to work, so he tweeted his question and received a response from his professor and a practicing professional. Both pointed the student to different resources that provided directions on how to embed music and examples that he could deconstruct. Within a half hour, the student had embedded music in his presentation.

- As part of a research project into emerging trends in e-learning professional preparation, a student posed the following question to the Twitter community: "With all of the Web 2.0 tools available today, do e-learning professionals still need to be able to program in HTML and XML?" She received responses from several e-learning professionals, some with links to helpful resources and contacts that could help her with her research.

Our thinking about Twitter as an approach to engaging students in the professional CoP has been influenced by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger's work in situated learning.41 Our particular use of Twitter, we believe, offers opportunities for students to gradually acquire the characteristics and norms of a CoP. Their legitimate peripherality allows them to absorb and be absorbed in the culture of practice, making it — as shared and illustrated in Twitter — their own.

Professional Exposure

When students connect with the professional CoP, it is a great way for them to share and get feedback on their ideas, work, and products and thus establish themselves as contributing members of the community. Using Twitter, our students networked with the authors of the texts they read in their courses, as well as with potential future colleagues and employers. By participating in Twitter within the supportive structure of a course, students learn how to guide and direct their online footprint in ways that highlight and showcase their professional qualities and value. The following example demonstrates how our students used Twitter for appropriate professional exposure:

Students used Twitter to promote new blog entries. For example, one student tweeted that he had a new post on his blog about how vision trumps all other senses during instruction. His classmates and professors, as well as practicing professionals, read his blog post because of his Twitter promotion. Subsequently, he received several tweets from the professional community thanking him for sharing his ideas.

Writing Concisely and Appropriately

Although Twitter elicits open sharing and an informal writing style, it is nevertheless critical to know your audience and share accordingly. A tweet's limit of 140 characters encouraged students to write clearly and concisely. Participating in Twitter helped them learn to be sensitive to their audience and to make professional decisions about what they should share publicly and what they should keep private.

Timely and Ongoing Connections

Our students used Twitter for time-sensitive matters: to ask us for clarification on content or assignment requirements, notify us of personal emergencies, and alert us to issues that needed our attention and action. This really helped them feel the level of connection needed to support their perception of engagement. We have also found that Twitter allows us to maintain ongoing professional relationships with students and alumni.

Positive Results

We believe that our focused use of Twitter has lead to positive results in terms of:

- Enhanced social presence

- Student engagement

- Professional preparation

The student comments throughout this article support our conclusion, as do those from a high-school project using Twitter in the classroom sponsored by the University of Minnesota and an experiment with classroom use of Twitter at the University of Texas at Dallas. As one of our students commented:

"I really LOVE twittering with everyone. It really made me feel like we knew each other more and were actually in class together."

We plan to continue our use of Twitter, as well as other social-networking and Web 2.0 tools, to extend the power and affordances of the LMS to create the best possible learning experience we can for them and for ourselves.

Benefits for On-Campus Courses and In-Person Settings

Although our focus has been on using Twitter in online courses, it can also be effectively used in on-campus courses and in-person settings. Two strategies that work well are back-channeling and polling.

Back-channeling

One benefit of using Twitter in on-campus courses is tapping into the back channel of communication. Back-channeling is a term linguists use to refer to the feedback listeners share — without interrupting the speaker — related to their developing understanding and appreciation of what is being said, which is then monitored by the speaker.42 Long before Twitter, John Seely Brown spoke in a keynote talk about the power of leveraging the back channel for instructional purposes. As it turns out, Twitter is an effective way to create a back-channel forum during a lecture or presentation: all users need is a Twitter account and ideally a projector to project the Twitter stream for the audience and speaker to monitor.

On the negative side, back-channeling can be counterproductive — sometimes even hostile and unprofessional — if appropriate rules of professional engagement are not defined and followed. In some instances people have used Twitter to "tweckle" speakers. To tweckle is to "abuse a speaker only to Twitter followers in the audience while he/she is speaking."43 Recent reports in the Chronicle of Higher Education44 suggest that if you have not heard of tweckling yet, it's only a matter of time.

Danah Boyd, a Social Media Researcher for Microsoft, was one of the most recent and high-profile victims of tweckling at a major conference.45 Boyd shared her experience and pointed out problems with tweckling in general but specifically in broadcasting the back channel during a talk: it can distract those who actually do not want to participate in the back channel and enable tweeters to take over a talk via the Twitter stream, thus making the back channel the front channel.46 Experiences like Boyd's have led some conferences to publish "social-media 'courtesy' guidelines"47 and others to restrict its use.

Before introducing back-channeling into your classroom, therefore, it is important to establish its relevance in support of student engagement and learning, set clear guidelines (the twitiquette), model appropriate back-channeling etiquette, and revisit back-channeling's effectiveness throughout the semester.

Polling

Twitter can also be used the way clickers are used for polling in the classroom. A number of different Twitter polling tools are available, such as twtpoll, Poll Everywhere, and StrawPoll. Some, like Poll Everywhere, even enable students to vote on the web or with text messaging.

Polling can enhance student engagement during a class as well as provide information regarding the students' conceptual understanding. One approach to using Twitter as a polling tool is to engage students in think-pair-share activities during lectures and presentations. Faculty pose a question to students, students think about their responses, and then students tweet their answers. Next, students confer with one to two partners sitting close by, and then retweet answers. This approach fosters student engagement by providing a clear structure for students to reflect, discuss, and self-assess.

Conclusion

Social-networking tools offer us unprecedented ways to connect, share, participate, and contribute in a variety of activities. Although we have focused on Twitter, it certainly is not the only social-networking tool that can be used to effectively pursue instructional objectives. Our colleagues in music performance, for example, prefer MySpace because students can easily share their music; our business school colleagues like LinkedIn; and our colleagues coordinating school and university library programs prefer Facebook and Ning because online professional CoPs exist in these environments. One size does not fit all, so we are lucky there are so many social-networking options.

Social networking, including the use of Twitter, has its drawbacks. It is public, you get what you put in, and it takes a lot of time. Of these drawbacks, the time commitment is perhaps the most important. We highly recommend trying Twitter first to see if you get any personal/professional value out of it before integrating it into the classroom. Twitter is not for everyone, and different faculty from different disciplines might have very different experiences using it for instructional purposes.

We selected Twitter because it:

- Allows for the just-in-time, free-flowing connection between and among students and faculty needed to support student engagement, especially in online-education settings

- Helps students build relevant PLNs that support their learning and professional development while enculturating them into the professional CoP

- Encourages students to reflect on what they share publicly and how to use Web 2.0 tools like Twitter to establish a professionally appropriate footprint

- Allows us to continue our connections with students long after our courses end

We are embarking on our own research into how effective Twitter and other social-networking and Web 2.0 tools are in helping us achieve the instructional goals of enhanced social presence, student engagement, professional preparation, and student learning. Because the use of social-networking tools like Twitter for instructional purposes is still emerging, there are many opportunities for research. As others have before us,48 we encourage researchers to examine the relationship between faculty and students and the learning strategies employed, rather than just the impact of the technology in isolation. To this end, in our own inquiry we are examining the following questions:

- Are students' perceptions of their level of engagement in a graduate-level online course enhanced by the use of Twitter as a vehicle for increasing the level of contact and interaction between them and their instructor?

- Does the use of Twitter enhance social presence in a graduate-level online course by providing a mechanism for just-in-time social interactions?

We are encouraged by the comment of one student who used Twitter in a course:

"Twitter was a big part of my connected-ness, with my PLN, course colleagues and with you. Even though I didn't post a lot of tweets, I watched the Twitter dialogue. It made the connections stronger and helped me learn more about folks in the profession, the course, and you. And, Twitter led me to some great resources and people for my PLN. Thanks, Joni, for being such a responsive Twitter-er."

We embrace social-networking tools like Twitter because they allow everyone who wants to participate in an online professional CoP to do so. In social-networking communities, all voices are welcome if they serve to advance the community's understanding of the world. To this end, we invite you to share your thoughts with us. Let us know what you think about using social-networking tools like Twitter to support student engagement and learning by completing the following poll: http://twtpoll.com/7jwv08.

Using Twitter, we can extend our conversation of the use of social-networking and Web 2.0 tools to support student engagement and learning. After all, Twitter and other social-networking tools allow us all to make noises in greater amounts and recognize that every voice counts. So, as Twitter demonstrates every moment of every day, a contribution is a contribution — no matter how small.

Further Reading and Resources

The Basics of Twitter:

Twitter and Education:

- Using the Power of Twitter: Building Online Learning

- 25 ways to teach with Twitter

- Twitter Literacy

- Professor Encourages Students to Pass Notes During Class "via Twitter

- How Twitter Can Enhance Your Presentation

- Introduction to Twitter

- How to Present While People Are Twittering

- Twitter as Courseware

- Professors Experiment with Twitter as Teaching Tool

- How One Teacher Uses Twitter in the Classroom

- Twitter for Learning Survey

- Can We Use Twitter for Educational Activities?

Twitter Polling and Quiz Apps:

Twitter Widgets and Tools:

Twitter and PowerPoint:

- Poll Everywhere (using Twitter in PowerPoint)

- PowerPoint Twitter Slides

Notes

- Joni Dunlap and Patrick Lowenthal, "Tweeting the Night Away: Enhancing Social Presence with Twitter," paper presented at EDUCAUSE 2009, Denver, CO.

- See Alan Haskvitz, "Twitter in the Classroom," Reach Every Child; and Kate Messner, "Making a Case for Twitter in the Classroom," School Library Journal (December 1, 2009); National Education Association, "Can Tweeting Help Your Teaching?" NEA Today Magazine, (2009); and Laura Walker, "Nine Reasons to Twitter in Schools," Tech & Learning, (April 16, 2009).

- Michael Moore, "Theory of Transactional Distance," in Theoretical Principles of Distance Education, Desmond Keegan, ed. (New York: Routledge, 1993), pp. 20-35.

- George Kuh, "How Are We Doing at Engaging Students?" About Campus, vol. 8, no. 1 (March/April 2003), pp. 9-16.

- Ellen A. Skinner and Michael J. Belmont, "Motivation in the Classroom: Reciprocal Effects of Teacher Behavior and Student Engagement Across the School Year," Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 85, no. 4 (1993), pp. 571-581.

- Arthur W. Chickering and Zelda F. Gamson, "Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education," AAHE Bulletin, vol. 40 (1987), pp. 3-7.

- George Kuh, "Assessing What Really Matters to Student Learning: Inside the National Survey of Student Engagement," Change, vol. 33, no. 3 (May/June 2001), pp. 10-18.

- Joe F. Donaldson and Steve Graham, "A Model of College Outcomes for Adults," Adult Education Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 1 (1999), pp. 24-40, see p. 28.

- Arthur W. Chickering and Stephen C. Erhmann, "Implementing the Seven Principles: Technology as Lever," AAHE Bulletin, (October 1996), pp. 3-6.

- Tisha Bender, Discussion-Based Online Teaching to Enhance Student Learning (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2003).

- See Patrick Lowenthal, " Social Presence," in Encyclopedia of Distance and Online Learning, Patricia L. Rogers, Gary A. Berg, Judith Boettcher, Caroline Howard, Lorraine Justice, and Karen Schenk, eds. (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2009), pp. 1900-1906; and Patrick Lowenthal, "The Evolution and Influence of Social Presence Theory on Online Learning," in Online Education and Adult Learning: New Frontiers for Teaching Practices, Terry T. Kidd, ed. (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2010), pp. 124-139.

- John Short, Ederyn Williams, and Bruce Christie, The Social Psychology of Telecommunications (London: John Wiley & Sons, 1976).

- D. Randy Garrison, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer, "Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education," The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 2, no. 2/3, (Spring 1999), pp. 87-105, see p. 94.

- Michael Moore, "Theory of Transactional Distance," in Theoretical Principles of Distance Education, Desmond Keegan, ed. (New York: Routledge, 1993), pp. 20-35.

- D. Randy Garrison and Terry Anderson, E-Learning in the 21st Century(London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2003).

- See Terry Anderson, "Teaching in an Online Learning Context," in The Theory and Practice of Online Learning, Terry Anderson, ed. (Edmonton, AB: AU Press, Athabasca University, 2008), pp. 343-365; Steven R. Aragon, "Creating Social Presence in Online Environments," New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, vol. 2003, no. 100 (Winter 2003), pp. 57-68; Charlotte N. Gunawardena, "Social Presence Theory and Implications for Interaction and Collaborative Learning in Computer Conferences," International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, vol. 1, no. 2/3 (1995), pp. 147-166; and Matthew Lombard and Thersea Ditton, "At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence," Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 3, no. 2 (September 1997).

- See Patrick R. Lowenthal and Joanna C. Dunlap, "From Pixel on a Screen to Real Person in Your Students' Lives: Establishing Social Presence Using Digital Storytelling," The Internet and Higher Education (to be published in 2010); and Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Hot for Teacher: Using Digital Music to Enhance Student's Experience in Online Courses," TechTrends (in press).

- Tisha Bender, Discussion-Based Online Teaching to Enhance Student Learning (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2003); and Jane Vella, Listening to Learning, Learning to Teach (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997).

- Jonathan E. Finkelstein, Learning in Real Time (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006).

- Lev S. Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

- David Lebow, "Constructivist Values for Instructional Systems Design: Five Principles Toward a New Mindset," Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 41 (1993), p. 6.

- Gordon Pask, Conversation, Cognition, and Learning (New York: Elsevier, 1975).

- Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Learning, Unlearning, and Relearning: Using Web 2.0 Technologies to Support the Development of Lifelong Learning Skills," under review for publication.

- For more on Twitter see Vance Stevens, "Trial by Twitter: The Rise and Slide of the Year's Most Viral Microblogging Platform," TESLEJ: Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, vol. 12, no. 1 (June 2008); also see EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, "7 Things You Should Know About Twitter."

- Suzie Boss, "Twittering, Not Frittering: Professional Development in 140 Characters," Edutopia (August 23, 2009).

- Kate Messner, "Pleased to Tweet You: Making a Case for Twitter in the Classroom," School Library Journal, December 1, 2009.

- Ibid.

- Mizuko Ito, Sonja Baumer, Matteo Bittanti, Danah Boyd, Rachel Cody, Becky Herr-Stephenson, Heather A. Horst, Patricia G. Lange, Dilan Mahendran , Katynka Z. Martinez, C. J. Pascoe, Dan Perkel, Laura Robinson, Christo Sims, and Lisa Tripp, "Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media," John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, 2009.

- See Andrew Chen, "Friends Versus Followers: Twitter's Elegant Design for Grouping Contacts," (March 16, 2009); and Joshua Porter, "Relationship Symmetry in Social Networks: Why Facebook Will Go Fully Asymmetric," Bokardo.com (March 29, 2009).

- See Danah Boyd, "Living and Learning with Social Media," presentation at the Symposium for Teaching and Learning with Technology (April 18, 2009).

- Steve Thornton, "Twitter Versus Facebook: Should You Choose One?" Twitip (January 13, 2009).

- David Nagel, "Most Faculty Don't Use Twitter, Study Reveals," Campus Technology (August 26, 2009).

- Marc Beja, "Professors Are Not Sold on Twitter's Usefulness," Chronicle of Higher Education (August 26, 2009).

- Pete Cashmore, "60% of Twitter Users Quit Within the First Month," Mashable (April 28, 2009), http://mashable.com/2009/04/28/twitter-quitters/

- Others have also found that Twitter is a great resource sharing tool. See Erick Hilbert's Twitter post, "Twitter used as a resource gathering tool is very powerful in education," #educause09 (November 4, 2009).

- Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Learning, Unlearning, and Relearning."

- Joshua Porter, "The Opaque Value Problem (Or, Why Do People Use Twitter?)" Bokardo.com (June 22, 2007).

- See Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991); and Etienne Wenger, Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press 1998) for more on communities of practice.

- Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Tweeting the Night Away: Using Twitter to Enhance Social Presence," Journal of Information Systems Education, vol. 20, no. 2 (2009), pp. 129-136.

- Wenger, Communities of Practice; John S. Brown, Allan Collins, and Paul Duguid, "Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning," Educational Researcher, vol. 18, no. 1 (1989), pp. 32-42; and Alan Collins, John S. Brown, and Ann Holum, "Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible," American Educator, (Winter 1991), pp. 6-46.

- Lave and Wenger, Situated Learning.

- Ron White, "Back Channelling, Repair, Pausing, and Private Speech," Applied Linguistics, vol. 18, no. 3 (1997), pp. 314-344.

- See Marc Parry, "Tweckling Twitterfolk: Chronicle Readers React to the New World of Twitter Conference Humiliation," Chronicle of Higher Education(November 18, 2009). Others have wondered if students "that is, not just conference goers "would also fall into this practice of heckling; for example, in a Twitter post (November 4, 2009) Pete Juvinall "#edtwitter #educause09 wonders about the dynamic of having student chatter displayed on a screen...and if there are hecklers that result."

- See Parry, "Tweckling Twitterfolk"; and Marc Parry, "Conference Humiliation: They're Tweeting Behind Your Back," Chronicle of Higher Education(November 17, 2009).

- See Parry, "Conference Humiliation"; Danah Boyd, "Web2.0 Expo Talk: Stream of Content, Limited Attention," Apophenia entry; and Danah Boyd, "Spectacle at Web2.0 Expo"¦ From My Perspective" (November 24, 2009).

- Boyd, "Spectacle at Web2.0 Expo."

- Parry, "Conference Humiliation."

- Stephen C. Ehrmann, "Asking the Right Question:What Does Research Tell Us About Technology and Higher Learning?" Change, vol. 27, no. 2 (March/April 1995), pp. 20-27; and Rebecca B. Worley, "The Medium Is Not the Message," Business Communication Quarterly, vol. 63 (January 2000), pp. 93-103.

© 2009 Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license.