Research conducted by the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) has shown that chief information security officers (CISOs) are human beings. That is, however, not enough for information security leadership.

A recent report by the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC) and ECAR identified 13 essential roles an information security leader plays (shown in figure 1) and the skills necessary to fulfill those roles.

Figure 1. A model for information security leadership

As part of its series of studies of the IT workforce in higher education, ECAR conducted a survey of CISOs to identify the functions of the position and the characteristics of those in it. Two questions were developed for this survey, based on these roles and skills. The first question asked how important it is for a successful higher education information security leader to master each of these roles.1 The second question asked respondents to evaluate the extent to which they themselves possess a set of skills and abilities necessary to fulfill each of the model's roles.2 Two or three skills and abilities in this question rolled up into each role.

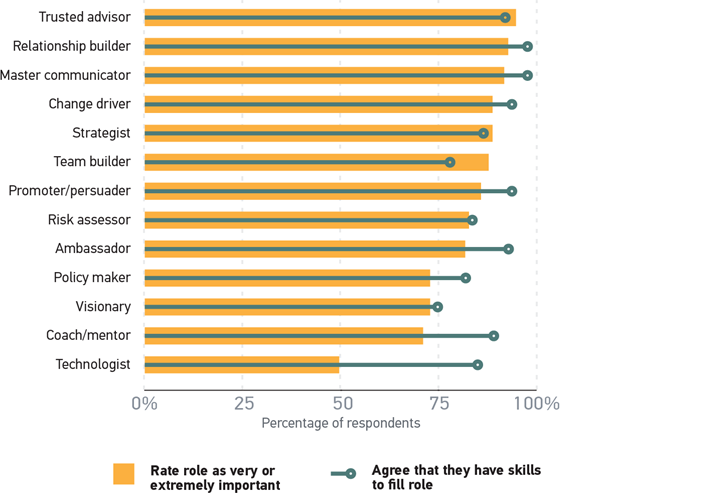

CISOs consider it important for a successful information security leader in higher education to master almost all of these roles. As figure 2 shows, the top three roles — rated as very or extremely important by greater than 90% of CISOs — are trusted advisor, relationship builder, and master communicator. Notably, this is one role from each ring in the CISO leadership model, and all three are roles for which trust and interpersonal relationships are critical.

Figure 2. Importance of leadership roles and possession of skills for success

All roles but one were rated as very or extremely important by 70% or more of CISOs. The sole exception is technologist, which fell dead even, with exactly 50% rating it as very or extremely important; a further 41% rated technologist as only moderately important. This is a curious finding, given the deeply technical nature of information security work generally. Many CISOs come from a background in other information security positions, which would naturally both require and provide opportunities to gain further technical skills. However, in the words of the business educator and coach Marshall Goldsmith, "What Got You Here Won't Get You There." In other words, technical skills may have enabled CISOs to gain that position, but once they are in that position, other skills become more important.

In its series of studies of the IT workforce in higher education, ECAR has found what others have suggested: that IT leadership is about relationship building, leadership skills, and strategic planning more than it is about technology.3 Respondents to the CISO survey indicated that these "soft skills" are not simply critical to success in the position, they are far more valuable than technical skills. Indeed, one witty respondent recommended that anyone aspiring to the CISO position should learn soft skills first because "the hard skills are much easier to develop."

Figure 2 shows that CISOs believe that they mostly possess the skills and abilities necessary to fulfill each of the model's roles. Notably, CISOs believe that they are most overqualified to fill the technologist role, which is of course consistent with other skills becoming more important once one is in that position. Recall that these skills and abilities roll up into the roles in the CISO leadership model. Most CISOs agree or strongly agree that they possess the skills to adequately fill these roles. But even a glance at figure 2 makes it clear that this is not universal. While most CISOs believe that they possess these skills, some do not. And of course, the skills that CISOs believe they possess vary from individual to individual.

It is clear from the data that there are many opportunities for professional development in the field of information security. CISOs clearly have a measure of self-awareness with regard to the skills that they possess and those in which they are not as strong. Furthermore, more than half of CISOs say that they intend to earn another certification. It would behoove organizations providing professional development on topics related to information security and leadership to take note of those areas that CISOs have self-diagnosed as gaps in their own skills. A ready audience awaits.

Notes

- Responses to these questions were on a Likert scale, ranging from Not at all important to Extremely important.

- Responses to these questions were on a Likert scale, ranging from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree.

- Jeffrey Pomerantz, IT Leadership in Higher Education, 2016: The Chief Information Officer, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, March 2017). Jeffrey Pomerantz and D. Christopher Brooks, The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape Report, 2016, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, April 2016); EDUCAUSE and JISC, Technology in Higher Education: Defining the Strategic Leader, March 2015; and Boris Groysberg, L. Kevin Kelly, and Bryan MacDonald, "The New Path To the C-Suite," Harvard Business Review, March 2011.

For More Information

For more on the role of the CISO in higher education, read the ECAR report IT Leadership in Higher Education, 2016: The Chief Information Security Officer, the third of four leadership reports in the EDUCAUSE IT Workforce in Higher Education, 2016 research series. Reports on the chief information officer and the enterprise architect are now available. A report on the chief data officer will be published later in 2017.

This IT workforce research and all ECAR publications are now available to individuals at EDUCAUSE member organizations under the new, all-in-one membership.

Jeffrey Pomerantz is a senior research analyst for EDUCAUSE.

© 2017 Jeffrey Pomerantz. This EDUCAUSE Review blog is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0.