January 28 is Data Privacy Day. Throughout the months of January and February, the EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Initiative will highlight higher education privacy issues. To learn more, visit StaySafeOnline.

Computerization is robbing individuals of the ability to monitor and control the ways information about them is used….The foundation is being laid for a dossier society, in which computers could be used to infer individuals’ life-styles, habits, whereabouts, and associations from data collected in ordinary consumer transactions. Uncertainty about whether data will remain secure against abuse by those maintaining or tapping it can have a “chilling effect,” causing people to alter their observable activities.

—David Chaum, 19851

Higher education rightfully prides itself as being a place where freedom of expression, intellectual discourse, dissenting views, and social experimentation are not just the norm but expected. The ability to engage in any or all of these activities is best done when an individual is not concerned with being (potentially or actually) under surveillance — as Chaum recognized, surveillance can have a “‘chilling effect,’ causing people to alter their observable activities.”

Privacy professionals often think of privacy in two distinct but occasionally interrelated categories:

- Data Privacy: Having to do with the collection, use, and sharing of information about individuals. Most of the privacy-related laws we are familiar with (FERPA, HIPAA, etc.) fall into the data privacy category.

- Autonomy Privacy:2 Having to do with the ability of individuals to be free of actual or potential observation. Autonomy privacy is strongly tied to freedom of thought, association, expression, and other civil and individual liberties and is most often associated with use of surveillance activities like audio/video capture.

In the digital age, we all too often focus on data privacy and its legal and compliance requirements. In doing so we forget the dictionary definition of privacy (which includes “being apart from…observation”), and risk losing track of how pervasive and quickly data collection, big data, and data science are creating autonomy-privacy issues that can impact free expression or dissenting views as much as pervasive security cameras or wiretaps.

There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system...they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted.

—George Orwell, 19481

Every boy in this land grows to be his own man.

In this land, every girl grows to be her own woman.

—Bruce Hart, 19723

What does it mean to be under threat of constant surveillance? Why is it particularly important for colleges and universities to recognize, as the University of California system explicitly did, that privacy must also be defined as being free from surveillance?

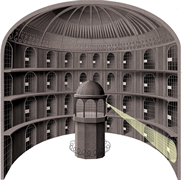

In 1984, George Orwell wrote about a bleak world where citizen control was predicated on perpetual surveillance (actual or assumed). In his version of the Panopticon, plugging into “your wire” meant the government could be watching you at any time via cameras or your own TV, eerily foreshadowing a world where the NSA and others have the ability to spy using webcams.

The Panopticon is a marvelous machine which, whatever use one may wish to put it to, produces homogeneous effects of power. Michel Foucault

There is more to lose even if you think you have nothing to hide!

In his book Surveillance Studies, Professor David Lyon defines surveillance as “the focused, systematic and routine attention to personal details for purposes of influence, management, protection or direction.” He adds that “surveillance is primarily about power, but it is also about personhood.”

The debilitating effects of surveillance on personhood or an individual are legion. Research has shown time and time and time again that the threat of constant surveillance can lead to individual stress, conforming behavior, intolerance of differences, curtailment of free speech and association, devaluing of individualism, and squashing of dissent.

Taken further, if we believe social scientist Irwin Altman’s statement that “building and maintaining an enduring, intimate relationship is a process of privacy regulation,” then surveillance restricts and/or damage personal relationships (which is exactly what happened to characters Winston and Julia in Orwell’s 1984).

Now think about the world of higher education:

- Students as young adults, learning through trial and error, experimenting and exploring, growing as individuals, creating some of their first intimate adult relationships, making mistakes, taking social and political positions, discovering themselves through academics and social interaction. Without autonomy privacy, could every boy in this land grow to be his own man or every girl grow to be her own woman?4

- Faculty and researchers researching through trial and error, experimenting and exploring, making mistakes, making and taking social and political positions. Is it any wonder that Fascist states, from Stalin to Hitler to Salazar to Honecker to Peron, relied on surveillance and suppressed academic freedom?

And in the End

Colleges and universities are supposed to be bastions of creativity and intellectual freedom, places where cutting-edge and sometimes controversial thought and research take place on a daily basis. In addition, historically they are often cradles and hotbeds of protest, dissent, and free expression. Privacy feeds those traits, which is why it has traditionally been a closely held value in higher education (so much so that during the course of privacy stakeholder conversations at the University of Michigan, one now-retired executive responded to my question “Do you think privacy is important or valued at U of M?” by staring at me with a puzzled expression and stating “I have never considered it, because I have always assumed it was”).

If we lose track of privacy in higher education, what does that mean for the rest of society going forward? What inventions or sociopolitical voices might be lost without privacy being a part of the higher education culture?

I would like to see our colleges and universities double down on privacy and explicitly discuss its importance and value in the academy, and the world in general. Higher education is uniquely positioned to engage in multidisciplinary collaborations that tie together the legal, sociopolitical, historical, and technical aspects of privacy. I would like to see faculty, researchers, higher education privacy officers, and other stakeholders work together to educate and empower their community, in particular students, by teaching them privacy’s vital role in self and society, and train them to be privacy conscious. In short, privacy matters.

Notes

- David Chaum, “Security without Identification: Transaction Systems to Make Big Brother Obsolete,” Communications of the ACM 28, no. 10, October 1985.

- The traditional, legal definition of autonomy privacy is tied to the freedom of individuals to choose whether or not to engage in certain acts or activities (often tied to sexual or reproductive rights). For purposes of this blog, I am using the University of California system Privacy and Information Security Steering Committee Report definition of autonomy privacy, which is “an individual’s ability to conduct activities without concern of or actual observation.”

- These lyrics are from a song titled "Free To Be... You And Me" written by Bruce Hart. The song was included as part of the 1972 album and project of the same name. The title of this blog acknowledges this project and song.

- Ibid.

Sol Bermann is the university privacy officer and interim CISO at the University of Michigan.

© 2017 Sol Bermann. This EDUCAUSE Review blog is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.