Key Takeaways

-

How can higher education institutions worldwide support transforming educational needs with the right tools at the right time?

-

Next generation digital learning environments must meet the requirements of evolving learning methodologies, the realities of the new life-long student demographic, and constantly evolving hardware and software technologies.

-

New, openly defined, and evolving models, standards, and data formats for capturing and sharing educational knowledge in programmatically accessible ways will stimulate the emergence of new educational businesses and services.

At the time the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative wrote its leading-edge report on Next Generation Digital Learning Environments (NGDLE),1 other countries conducted research on this topic as well. In the Netherlands, the effort is organized on a national scale, where they choose a generic approach for all institutions of higher education to create a digital learning environment (DLE) that supports flexible and personalized learning. In Spain, the Open University of Catalonia (UOC - Universitat Oberta de Catalunya) chose to collaborate with MIT to develop a concrete architecture based on the NGDLE principles for its new virtual campus. Although these approaches differ, they share the same goal: to create the right conditions for the NGDLE.

SURF: Support for Institutions on a National Level

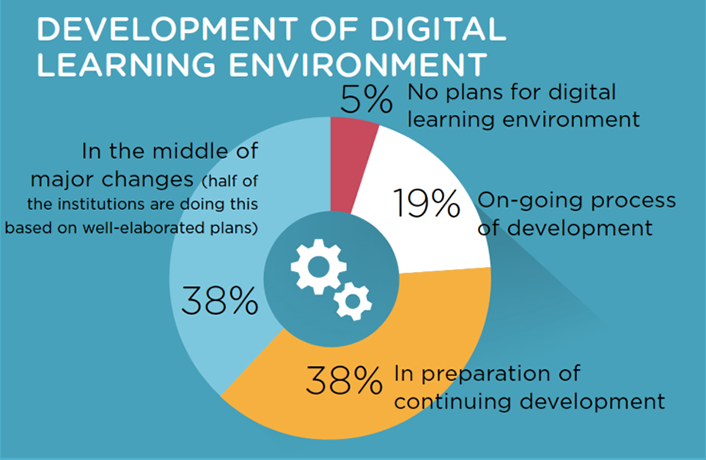

A 2016 survey conducted in the Netherlands revealed that more than 75 percent of higher education institutions are working on a DLE (figure 1).2 Not only do institutions feel the need to get more control of the tools and applications used by students and staff, the license agreement with Blackboard had expired at most of the institutions, requiring them to launch a new call for tenders. For many institutions this marked a starting point in thinking about the DLE.

Many institutions endorse the idea of a DLE consisting of interchangeable and expendable components. In some settings, they already experiment with this concept. But when the learning management system (LMS) has to be replaced, most institutions still opt for an all-in-one system because their requirements for a modular learning environment are not well defined. Implementing a modular DLE also involves technical and organizational issues.

Joint Approach to Tackling DLE Issues

Institutions don't have to reinvent the wheel. SURF, the collaborative IT organization for Dutch education and research, has the mission to enhance their quality through innovations in information and communication technology (ICT). One of the topics SURF addresses is the DLE, with the main goal of enabling institutions to create a DLE that supports flexible and personalized learning. SURF seeks generic problems to address with the institutions in order to involve all relevant institutional experts and, together, do the work that institutions otherwise would do by themselves. The main generic issues in the Netherlands follow.

Does the DLE support the institution's vision of education? To what extent does an institution's vision of education influence or determine the choice of a DLE? Discussions with representatives of institutions for higher education as well as a roundtable meeting with these representatives resulted in a thematic publication of the SURFnet magazine,3 which any institution can use when questioning the way their DLE should support their vision of education. It gives global requirements implied for the DLE, based on contemporary pedagogical trends.

An interesting organizational paradox came to light: Translating the vision of education into a pedagogical model and didactic applications often takes place at several levels within a university or college: department, cluster, program, course. However, the responsibility for and decisions regarding the DLE are often made at a central level within the institution. At that level, it is impossible to fulfil all the various wishes and requirements associated with the digital environment. Having said that, the DLE must adequately support as many different educational and learning processes as possible. The choices made at the institutional level must therefore allow for sufficient flexibility at the individual program level while generating sufficient control for the institution.

An important pedagogical trend is that institutions define learning outcomes rather than a predefined curriculum. Learning outcomes describe what a student knows, understands, and can do after completing a learning process.4

The DLE must offer effective support for both teachers and students so that students can take responsibility for their own learning process. For this to occur, the DLE must provide a clear and transparent overview of the activities offered and the associated tasks and deadlines. It also requires greater variances for different learning pathways and learning formats. Furthermore, insight into the learning process of individual students and groups, for example via (peer) feedback, must be possible. Finally, collaboration with others must be possible, within the boundaries of the institution itself as well as externally.

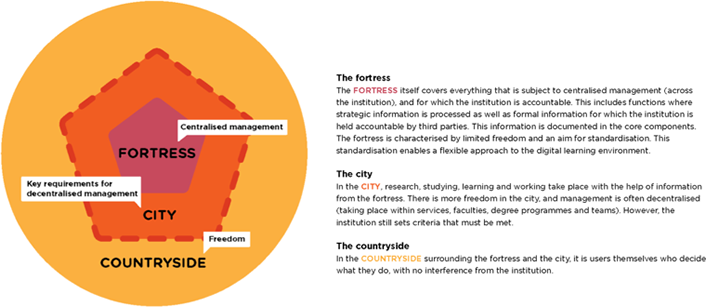

How can an institution manage the application landscape? How should they support reliability, safety, and freedom of choice for users? In the Netherlands, institutions developed the metaphor of the fortress and the open city (figure 2) to decide which tools to manage centrally, what to manage decentrally, and what not to manage.

Many Dutch institutions use this model for their own organization. The model pops up in a lot of presentations or vision statements on the DLE because it offers an easy way to discuss the issues and helps in deciding where the components must be placed in the architecture of the DLE. Often, institutions have a tendency to place everything in the fortress, but this is not always the best option. With this metaphor, a balanced choice can be made. It also has created a common language for everyone within an institution who works with the DLE.

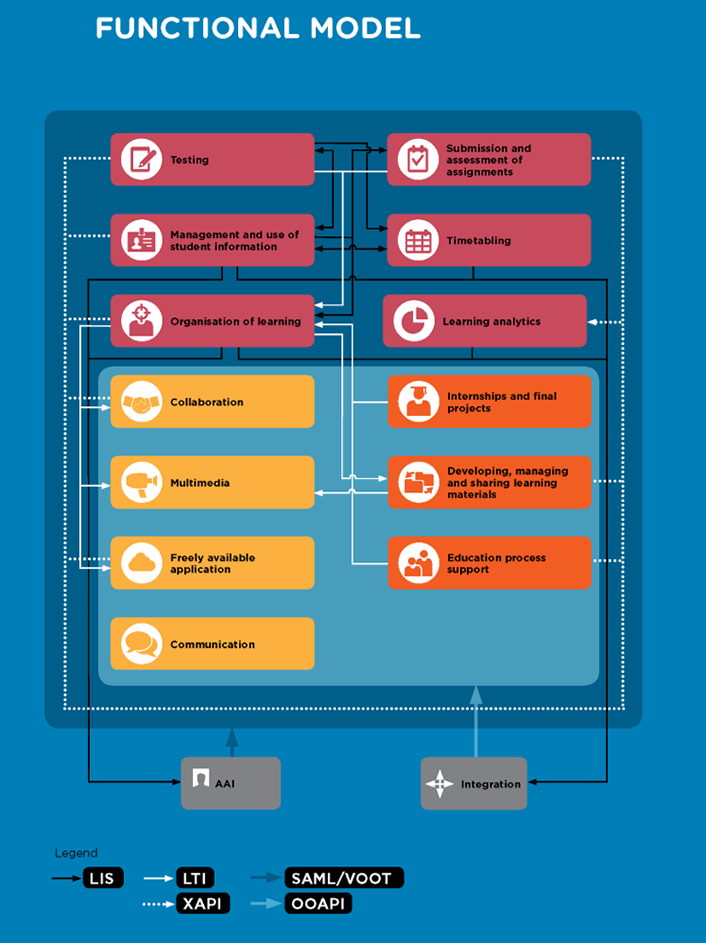

How can an institution ensure the interoperability of various applications? The EDUCAUSE report points out a range of initiatives that are shaping this vision of the NGDLE, but it also states that a lot of work is necessary to achieve it. In the Netherlands, we have worked on a generic architecture based on the characteristics of the NGDLE.5 In this model architecture content and functionality are derived from multiple components, and it has interoperability standards to allow separate systems to work together. Such "components" provide functionality for the effective performance of an education task. Here, functionality refers to the entirety of possible applications (i.e. functions). What components will make up the next-generation digital learning environment? What is needed to make a DLE personal and flexible? And what will integration require?

Together with 10 institutional architects from various universities we researched every component:

- Which data has to be exchanged with which other components

- The standard that should be used

- Whether the data exchanged between the components is incoming or outgoing

This resulted in a functional model that universities can use in the design of their DLE.6

This functional model defines the five most important standards for a DLE: IMS LTI (Learning Tools Interoperability and integration), IMS LIS (Learning Information Services for personalization), xAPI (analytics), SAML/VOOT [https://openvoot.org] (collaboration), and OOAPI (accessibility and universal design).

How can an institution ensure that services comply with relevant standards? Suppliers also play an essential role in realizing a DLE. At this moment, few vendors fully support modular interoperability. Vendors do offer (parts of) packages, but these often do not interoperate with other systems. We can only achieve the goal of a modular DLE if vendors adopt this approach. This requires a shift from service providers: they need to open up their services to use the relevant standards and offer different license models.

SURFnet challenges vendors to show institutions how their products contribute to the approach of a modular DLE. SURFnet developed a demo environment in which suppliers can show extent to which their service is compatible with relevant standards. Doing this on a national level supports both suppliers and institutions. Vendors only have to make one connection and show it to all institutions in the Netherlands. Institutions can take advantage of all the knowledge built into the demo environment. A few vendors have already accepted the challenge, and we hope many others will follow soon.

The remaining question is: How can an institution use the right tools and design the user interface in accordance to educational methodologies and pedagogical models at the institutional level? MIT and the UOC collaborated on an enterprise architecture that enables this, as described next.

UOC/MIT: Supporting Learning Technologies in Higher Education

The UOC and MIT, higher education institutions headquartered in Barcelona (Spain) and Cambridge, Massachusetts (USA), respectively, have a history of international collaboration.

The UOC was the first distance learning university in the Catalan higher education system. A fully online university begun in 1995 with an educational model based on personalization and continued support to students using e-learning, the UOC has around 54,000 students; 6,438 virtual classrooms; 2,988 course instructors; and 366 faculty and research staff.7

The Strategic Education Initiatives (SEI) unit of the Office of Digital Learning (ODL) supports MIT's partnerships with other universities, foundations and trusts, nongovernmental organizations, and national governments to experiment with and implement digital learning. Some SEI projects span nations and hundreds of schools, helping to advance the field of digital learning for practitioners, researchers, and learners at MIT and around the world.

The UOC and MIT (through SEI/ODL) have been collaborating on learning technologies projects since 2006.

Modern learning technologies must allow students to learn and instructors to teach anywhere at any time, regardless of their physical location. Today, for example, resident students in a hospital can interact online with faculty in different locations and countries, rather than only through face-to-face interactions in a university hospital. With these technologies we can enable educational experiences where and when they are needed the most, including workplace locations — hospitals, laboratories, factories, farms, and elsewhere.

This new educational reality requires educators and instructional designers to rethink some of the fundamental approaches to education. The instructor's role may move from the teaching classroom to mentoring or coaching. Students may be required to take on a more active role, questioning their classmates and requesting mentoring from the instructor. At the same time, more meaningful learning methodologies are required: competency-based education, problem-solving approaches, or project-based learning are all gaining increased acceptance in support of next generation education experiences. The tools and services necessary to boost creativity, support the coaching dynamic, and nurture discussion and collaborative work among students will become more and more diverse and interactive. We will witness a proliferation of new methodologies and software services in the educational industry in the years to come.

Society has also been changing. Today's practitioners work in distributed, interdisciplinary, and international teams, and the progressive digitalization of the workplace has transformed most professions. Innovation is continuous in any field, requiring lifelong updating of skills. Online education is probably the best environment to provide both digital literacy and lifelong learning.

Approaching the Next Generation Digital Learning Environment

In 1995 not many DLEs were available, which is why the UOC developed its own. Today, the UOC's virtual campus uses a complex mix of technologies thanks to subsequent adaptations to user needs, technology upgrades, and pedagogical changes. In parallel, a worldwide Internet-based industry of learning technologies emerged and has grown ever since. Many vendors serve this sector and produce solid educational applications and learning systems.

The UOC, like many other universities, is committed to a vibrant education industry, believing that vendors are best positioned to deliver the next generation of educational technologies that universities will require. Therefore, the UOC is in the process of shifting from its self-made platform to a third-party platform, looking for vendors who will not only be a software and service provider but an educational partner too.

The EDUCAUSE NGDLE report offers a clear vision of DLE evolution. Consequently, a year ago the UOC and MIT worked together to envision a next-generation enterprise architecture that could better support this vision.8

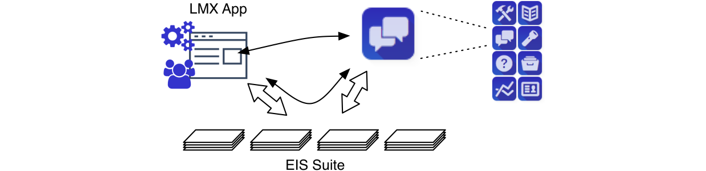

Figure 4 illustrates market components of this educational ecosystem represented as a relationship between three main elements: apps (upper right), learning services (Educational Infrastructure Services, or EIS, Suite, bottom), and a new concept, the learning method experience, or LMX (upper left).

The Apps. The apps — web, mobile, or whatever — allow personalization by providing the best resources for learning and teaching. Because every profession requires multiple and diverse apps, the apps marketplace encompasses all kind of digital applications — similar to common mobile apps stores and marketplaces. Standards like IMS LTI have proven that a marketplace of applications can indeed be supported for the needs of education, and can also be viable. As mentioned, the rapid rate of social change and lifelong updating of skills also compels a regular upgrade of the selected apps for learning and teaching as well as a need for integration into the educational.

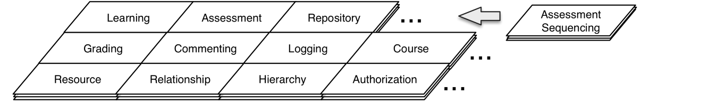

The Learning Services. Educational Infrastructure Services (EIS) in figure 4, a suite of services meeting the needs of teaching and learning apps provide the foundational functional elements to support institution-wide education and administrative business models. The implementation and consolidation of more specific educational business processes — like online assessment — will result in a progressive service disaggregation from the LMS to the enterprise. Education is a complex field in which the improvement and accuracy of each part will require specialized businesses. Next generation digital learning environments will need to support the deployment and sustainability — in terms of technology and business — of these new services separately from the LMS. At this point, the UOC is leading a project with 18 European partners called TeSLA [http://tesla-project.eu/] focused on the use of biometrics in an assessment process.9 This initiative will require new vendors, specifically biometric providers, and undoubtedly will have to be integrated into the educational ecosystem through new service contracts. At the same time, MIT has been implementing a growing body of learning-related services based on an extensive set of service definitions documented over the past 17 years. Figure 5 represents the growing suite of enterprise learning service components being developed at MIT.

The LMX. The acronym for learning method experience, LMX stands for an entity — the user interface or other mechanisms — which provides the context and overall user experience required for a particular educational methodology or pedagogical model. In today's LMS concept, LMX should be the set of views or access points to the learning and teaching process, such as course lists, notifications, calendars, new types of learning spaces, and more recently competency maps. The LMX concept encompasses the set of functionalities that allows academic staff to design an overall user experience in accordance with their educational methodologies and pedagogical models. In line with this concept, the central UOC requirement for its new DLE is the ability to design and set up new digital learning spaces, essentially different LMX environments for different programs. Table 1 shows examples of new types of digital learning spaces required at UOC, and Table 2 shows some possible user interfaces to access them.

Table 1. New types of digital learning spaces and their definitions

|

Learning Space |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

PLA |

Performance learning activity space. A new type of space for supporting performance-based learning |

|

Project |

A project management capabilities space; should contain tasks, some of which could be Performance learning activities |

|

Seminar |

A place to perform seminars |

|

Laboratory |

A place to perform experiments and to learn techniques and methodologies |

|

PhD |

A space for PhD programs, providing tools for interaction between PhD students and tutors; links to seminars; and labs for research |

|

External |

Provides access to an external learning space like a blog, MOOC, other LMS, social network, or any other space where learning and teaching processes would be performed |

Table 2. User interfaces providing access to the learning spaces

|

View |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

My Notifications |

User interface containing all the notifications in the system |

|

My Competencies |

A map, showing the relation between competencies and courses and progress achieved in their acquisition |

|

My Portfolio |

User interface showing all the assignments (from the beginning of the program); users able to mark each assignment as public or private |

|

My Learning |

Students access not only in-course learning activities but also those already completed (the latest version of them); this historical information sets the basis for new services related to lifelong updating of skills and knowledge |

Conclusions

The natural evolution of learning systems in response to these new educational and workplace realities means that the traditional, one-size-fits-all LMS is quickly going the way of the flip-phone. Next generation learning environments must meet the requirements of evolving learning methodologies, the realities of the new life-long student demographic, and constantly evolving hardware and software technologies.

Fundamentally, we are talking about new, openly defined, and evolving models, protocols, and data formats for capturing and sharing actual educational knowledge in programmatically accessible ways, to stimulate the emergence of new educational businesses and services. Eventually we would expect a rich and growing net of educational knowledge to lead to completely new kinds of Internet-based experiences and embedded technologies that go well beyond the current state-of-the-art of what is possible through web browsers (a technology that is itself over 25 years old).

The attempts to follow and address all these developments and achieve a suitable DLE are not unique. In America, the Netherlands, and Spain, work is being done to bring the DLE to the next level. These initiatives have now been brought together so that their resulting knowledge and experience can be shared even more widely.

Notes

- Malcolm Brown, Joanne Dehoney, and Nancy Millichap, "The Next Generation Digital Learning Environment: A Report on Research," EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, April 2015.

- SURFnet, "Infographic: The Digital Learning Environment in the Netherlands Anno 2016," November 7, 2016.

- From a Vision on Education to Organising the Digital Learning Environment, SURFnet, June 2016.

- Cedefop, "The Shift to Learning Outcomes: Conceptual, Political, and Practical Developments in Europe," Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, June 2008.

- A Flexible and Personal Learning Environment: From Single Components to an Integrated Digital Learning Environment: A Survey, SURFnet, September 2015.

- A Flexible and Personal Learning Environment: A Modular Functional Model, SURFnet, October 2016.

- These numbers are from the second semester of the 2015–2016 season.

- Jeff Merriman, Tom Coppeto, Francesc Santanach, Cole Shaw, and Xavier Aracil, "Next Generation Learning Architecture Report," UOC, March 2016.

- The European project TeSLA is coordinated by the UOC and funded by the European Commission's Horizon 2020 ICT Programme.

Marieke de Wit is project manager for SURFnet, The Netherlands.

Francesc Santanach Delisau is e-learning specialist, project manager and software engineer at the Open University of Catalonia (UOC - Universitat Oberta de Catalunya), Spain.

Jeff Merriman is associate director SEI, Office of Digital Learning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA.

© 2017 Marieke de Wit, Francesc Santanach Delisau, and Jeffrey Merriman. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.