Key Takeaways

-

To articulate scholarly research using richer methods of communication than straight text, students can apply audio-visual writing tactics.

-

Audio-visual writing uses video, photos, graphics, sound, and multimedia to explore sometimes advanced research concepts.

-

Students can employ various technologies to obtain the elements for their productions and other technologies to process and combine them in a smoothly blended presentation.

-

In addition to the pedagogical benefits of these projects, students learn how to use new technologies and develop stronger critical thinking and analysis skills.

In concise terms audio-visual writing is the articulation of scholarly research using video, photos, graphics, sound, and multimedia with text in a (usually) time-based presentation. I like to consider how the different forms of audio-visual writing relate to the different times in a student's career at the institution. Something like digital storytelling is really useful at an introductory level, for example. It's simple — assembling photos, including some voiceovers and sound, maybe inserting a little video here and there — yet it reinforces critical thinking and analysis skills.

![Frames of Mind, Jordan Tynes and Maurizio Viano, [in] Transition 2.1, Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, March 2015](https://er.educause.edu/-/media/images/articles/2017/5/ero17321image1.png)

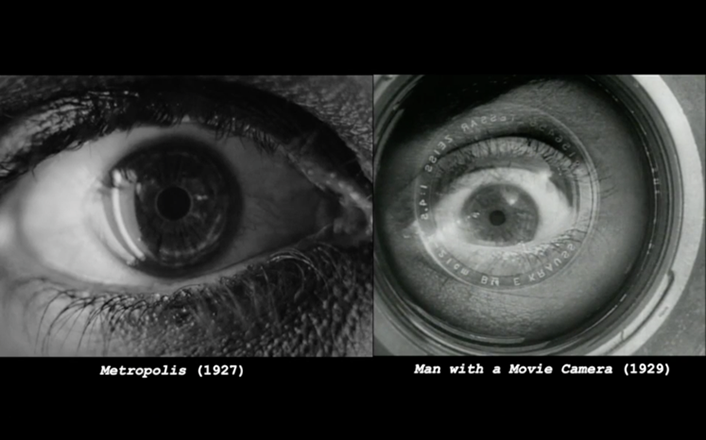

"Frames of Mind," Jordan Tynes and Maurizio Viano, [in] Transition 2.1, Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, March 2015

On the other end of the spectrum lie rigorous video essays, which have been used by students as a method for submitting thesis-level research. Students frequently write papers that respond to something visual they can document. Maybe they're analyzing a film, for instance, and so will digitize the film and go back and forth between the visual form and the written form, negotiating the process until the two blend and become seamless. Some of my students are working on 10- or 15-minute presentations as video essays. It's great to see these rich projects as the end result of a student studying audio-video materials across a four year degree.

I've also asked students to do video blogs, which get them more conversationally competent with the content of a course. They do some readings, maybe watch some screenings, study data of some kind, and then verbally respond to the materials and document their learning in a creative way. That engaged process gets them thinking rigorously and speaking fluently about the subject.

Podcasts have similar benefits. I ask students to create podcasts in the form of an essay. Sometimes they're a series; sometimes they're really long, one-off projects. There are lots of different ways to do podcasts — those are just some examples. All of which usually involve multiple voices and perspectives contributing to a topic.

You can take the technology that's common in all of those projects and play with the form that interests the student or faculty member, responding to how they want to articulate the concepts using different formats. The options are multifaceted and can be richer than solely text-based scripts.

"For my video essays, I usually assemble all of the footage first and before writing a script. Editing it all together makes the argument for me.... As a CAMS major we are taught to think about images and their relationship to each other. We reach so much more of our potential when we are allowed to do academic work in which we practically apply what we've learned."

—Carlyn Lindstrom, Class of 2017

The Technology

The resources available to students differ depending on where they are in their career at the college. I almost always design assignments to use the technology I have and can support. At an introductory level I might standardize the technology students use, such as giving them all the same camera. I might give them access to the same editing software so that everybody's sort of on the same level. Later I might open it up and say, "Okay, if you have a camera that you'd rather use, or if you have a different way of editing things, then you can try that." Sometimes in those cases students will inspire each other: "Wow, what they're doing is really cool. Can we train that way as well?" If I can support it, I often bring that particular method into the course.

I want to caution that audio-visual writing is a subjective exercise, not a big experiment in technology. I try to keep the tools from becoming a distraction to the students by making small adjustments throughout the semester, even in a foundational course. The technique has proven itself a good one to get students thinking about deep concepts implied by the course content, especially as first-years. In later years, students are empowered to explore more advanced tools for production, which might offer 10 or 15 ways of doing something rather than the few provided by simpler technology. As students carve their own path through the advanced technology, they are also creating a unique voice to parallel the concepts communicated by their research.

Assessment

When it comes to visual and digital storytelling, assessment has to change a bit. In addition to the textual content (voiceovers, etc.), there is also a visual element. Each assignment must make clear how much value will be placed on the aesthetic considerations when the project is assessed. If a student has successfully understood the content or the course goals and has managed to blend those well with an intentionally selected method or form of production, then I only make minor changes to my methods for assessment. If I'm asking students to produce a video essay, I might evaluate whether they are taking the project seriously, with appropriate attention to detail. These are things I consider when evaluating writing of any kind.

"The making of an audiovisual essay is a creative process: just like a filmmaker, I must consider how to combine text, music, video, and what their combined effect will be. Being able to explore and convey my reactions through audiovisual writing mobilized my creative forces to react as a participating viewer instead of a passive viewer."

—Nicole Zhao, Class of 2020

I might also ask, what level of experimentation is the student attempting? I often ask them to submit a supplementary artist's statement. An artist's statement describes the student's intent and what they were trying to accomplish with this form of visual writing. If those match up — if what I get from their visual writing matches what they say they're trying to accomplish — then they've done a great job. An artist's statement creates another layer of critical analysis for the student, as well as a one-off rubric for evaluating a student's work.

Distributing the Experience

One of my biggest goals in supporting new media has been to scale technical knowledge involved in the production process and distribute it evenly across a student's four-year experience. To do this, I approach different disciplines and ask them what the literacy requirements are for their programs, and then I brainstorm about how these alternative forms of expressing research fit with their curricular goals. Coming up with an integrated plan for audio-visual writing projects across disciplines suggests related goals for a student across a four-year experience.

"In terms of learning curves, I would say I really started to pick it up after about 8 months of practice... Once I was introduced to the basics of Final Cut Pro, I was really able to run with texting formats, edits, etc. This medium, especially, lends itself to creativity and control even for amateurs... Moreover, I think the fact that the academic field is so new, is very exciting. Each time I do a project, I feel as though I'm actually contributing something of importance to the academic community."

—Sophia Kornitsky, Class of 2019

What do students need to know about audio-visual writing techniques in their first year? Their second and third years? At each level, students are taking steps that build upon and expand their technical expertise, which help them meet requirements for their capstone projects. When the students graduate, what will they need to know about audio-visual writing and technologies to flourish in a work environment? How comfortable in this production process do they need to be? Certain relatively rigorous disciplines might not value visual writing at all, but they might be interested in some other form of new media. I want to break that down into logical elements and think about how those requirements can be evenly distributed across students' four-year experience at Wellesley.

"The Eye Is the Heart: Metropolis and the Kino-Eye," Sophia Kornitsky, Film Matters Magazine, March 17, 2017

Research and Experimentation

Research and development are relatively important in the area of audio-visual writing. If a discipline is interested in incorporating a type of new media that I've never heard of or am unfamiliar with, how can I research it and think about how a professional would produce something in that form? Then I need to break apart the process and think about how I can distribute it into the curriculum that already exists. When thinking about how to develop assignments, I realize that some of them might be relatively risky. Still, I think the greatest reward I've received from experimenting in these new forms comes from the highest risk situations — trying something in a class that's never been tried before. Those attempts require a relatively high amount of support from somebody who knows what they're doing technically. But if I can find a way to integrate the faculty member's goals for that course with the additional values they receive from that production, then the course will be more open to experimentation. I look forward to these opportunities to grow the methods and technologies used in audio-visual writing, with the goal of bringing my students along with me.

Jordan Tynes is the manager for Scholarly Innovations at Wellesley College.

© 2017 Jordan Tynes. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.