Key Takeaways

-

As efforts to stimulate innovation spring up across campuses, institutions need a comprehensive planning framework for integrated planning of initiatives to support innovation.

-

Viewing the campus as an Innovation Landscape, settings for collaborative creative activity — both physical and virtual — infuse the campus fabric and become part of the daily experience of their users.

-

The Innovation Landscape Framework proposed here serves as a tool that can help coordinate physical planning with organizational initiatives, engage a wide range of stakeholders, and enable a culture of innovation across campus.

Structured methods for innovation planning developed over two decades have been applied to many types of planning challenges, primarily in the corporate world.1 However, there are few innovation frameworks developed for application to academic campus planning, particularly based on an integrated planning approach.

Innovation initiatives in higher education for the most part have focused around how to stimulate work in STEM fields to increase the rate of discovery, how to foster interdisciplinary entrepreneurship, and how to address complex challenges through global academic collaboration. Trends in digital scholarship and pedagogy change also engage faculty, learners, and administrators in envisioning innovative directions for teaching, research, and other academic pursuits. Many students now enter higher education motivated to create new ideas and realize them. Physical planning responses have been to design buildings to foster greater interaction and to bring disciplines together in interdisciplinary research and academic buildings. Recently some institutions are creating innovation centers as a locus for inventive energy and to reframe their brand. Many others are introducing makerspaces — not just in engineering sectors but now in libraries, residences and potentially anywhere on a campus that promises to enhance learning.

To create a rich culture of innovation at an institution, though, requires articulating a wider planning vision — one that is more inclusive and encourages inventiveness across the many aspects of academic experience and operations. We propose a framework for an integrated planning approach that links academic strategic planning with physical space planning in support of innovation — the Innovation Landscape FrameworkSM.

What Is an Innovation Landscape?

Just as the Learning Landscape planning approach2 developed 15 years ago acknowledged that "learning happens anywhere," an Innovation Landscape approach seeks to create an environment where innovation can be supported, socialized, built, and tested anywhere and everywhere. An Innovation Landscape perspective can become integral to the campus culture and be clearly articulated by all the systems that support it. Everyone can be incentivized to contribute to a culture of innovation and encouraged by policies of the institution to continue to develop and support it.

What Does the Innovation Landscape Planning Framework Do?

- It structures a process that explores opportunities to foster innovation and then suggests coordinated approaches to maximize planning impact. It is a tool that can be adapted and developed to suit many types of institutional and planning situations.

- It visualizes a holistic system, built in the tradition of a service blueprint. Co-created by its users, it makes intangible efforts visible. It allows the visualization of interrelated activities and produces evidence, whether in the form of inventive ideas, physical artifacts, or other products of innovative activity.

- It supports integrated planning initiatives. It can be inclusive and generate detailed strategies for implementation, while simultaneously allowing for a comprehensive view at a high level for participants to understand the integrated vision. This can reveal nuanced relational opportunities between efforts that might appear unrelated and highlight the importance of communication between initiatives.

How Is the Framework Used?

The Innovation Landscape Framework is designed to promote better understanding of the rich diversity of ongoing and future efforts across an institution that supports innovation. It was developed to be used by institutional leadership and academic departments as a tool for productive discussion. Often, the efforts on the part of individual units of an institution are not visible to others.

The framework can be used in many ways, such as a:

- Strategic planning tool

- Visioning retreat workshop tool involving stakeholders

- Guide for ongoing task force deliberations

- Vehicle for campus community input

- Strategic roadmap for staff and administrators

The integrated nature of the tool can create opportunities for participants in the process to articulate and see their efforts in the context of a common initiative. The framework also provides a vehicle for visualizing and summarizing a collective action plan with broad reach that can help guide planners.

It is both a generative and an evaluative tool. At the beginning of the planning process it can be used to map and describe current innovation-related activities and develop concepts for new ones. It can help identify and establish consensus on goals and targeted initiatives. Institutions that are starting to build an innovation culture can use the framework to evaluate their degree of maturity under each of the planning principles. It can provide the structure to generate integrated approaches and concepts that multiple stakeholder groups can align around, both at the beginning of a planning process or while it is ongoing. Once the process has begun, it can be used to assess how efforts in each cell of the framework are or are not being supported and become a guiding document to keep participants up to date with progress.

What Elements Make Up the Innovation Landscape Framework?

The framework consists of five basic innovation planning principles and three planning lenses. It makes visible the dynamics between the five principles by seeing them through three planning "lenses." (See figure 1.) The planning principles that help foster innovation are intentionally broad and can be interpreted to apply to many types of campuses or initiatives:

- Connections

- Convergence

- Ecosystems

- Catalysts

- Process

Each principle is then applied from the perspective of the three planning lenses to generate possible planning strategies to enhance innovation:

- Physical Infrastructure: the campus network of activity settings, nodes, hubs, buildings, temporary structures, and exterior spaces

- Incentives and Policies: institutional incentive systems, policies, protocols and initiatives that encourage experimentation, risk taking and seeking of a vision — whether for pedagogy advancement, encouraging new directions in digital scholarship, or finding a new cure or invention to leverage

- Knowledge and Systems: the resources and information systems that support knowledge sharing and academic excellence, such as library and IT systems, institutional repositories, research data management, or virtual learning communities development

Figure 1. The Innovation Landscape Framework

How Is the Framework Matrix Developed?

This process of exploring implications through each lens uses the matrix to develop and articulate integrated planning strategies that can enhance innovation and collectively foster a culture of innovation. To illustrate some potential actions, we describe each of the principles with some example strategies or ways they might be applied as seen through each of the lenses.

Planning Principle 1: Connections

Encourage the interaction of people, resources, and information within and between colleges, schools, programs, and units

Physical Infrastructures lens examples:

- Rethink adjacencies between units and programmatic mixes to foster new research and working relationships

- Invest in informal meeting places to enable people to connect more easily for serendipitous dialogue and provide a wide variety of reservable collaborative and knowledge-sharing venues

- Develop circulation paths that enhance interaction, both internally and externally

Incentives and Policies lens examples:

- Incentivize interaction between colleges to connect potential collaborators

- Develop campus space availability/booking apps to enable groups to more easily find places to meet

Knowledge and Systems lens examples:

- Develop systems to help researchers and entrepreneurs find others working in their field of inquiry

- Enhance interactive displays around campus

Planning Principle 2: Convergence

Foster a culture of innovation and convergence strategies that encourage transdisciplinary discovery and erode silos institution-wide

Physical Infrastructures lens examples:

- Create places for making and prototyping that serve all sectors of the campus

- Celebrate discovery and innovation and make them more visible in the environment

- Create sufficient shared places for diverse groups to converge, such as bookable meeting rooms

Incentives and Policies lens examples:

- Incentivize research across domain areas and teaching with multidisciplinary problems and teams

- Focus institutional priorities on addressing complex global challenges

- Allocate budgetary resources and recruitment to promote interdisciplinary strengths

- Incentivize course redesign, active learning, and interdisciplinary teaching

- Reward academic innovation, especially outside of traditional tenure-track scholarship

- Leverage and support intellectual property development

Knowledge and Systems lens examples:

- Enhance systems for sharing of research, data, and scholarship

- Develop data analytical skills of learners at all levels across campus

- Support emerging communities of practice

Planning Principle 3: Ecosystems

Cultivate entrepreneurial ecosystems with industry, other institutions, alumni, local communities, and global academic communities

Physical Infrastructures lens examples:

- Create facilities to collaborate with industry partners and alumni on new ventures

- Develop an area adjacent to the campus as a vibrant mixed-use innovation district

- Link on-campus work to global experiences and leverage a network of global collaborators

Incentives and Policies lens examples:

- Develop support systems and services that enable students and faculty to pursue their entrepreneurial aspirations

- Promote entrepreneurship in service of the institutional mission and strategic plan

Knowledge and Systems lens examples:

- Foster awareness of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, making visible potential opportunities, services, and resources

- Develop expertise about intellectual capital and scholarly communications in a rapidly changing environment

- Support development of data science

Planning Principle 4: Catalysts

Create experiences that are catalysts for creativity and make evident the institution's innovative spirit

"Catalytic experiences" are active experiences that help build community, are meant to be transitory, and allow risk-taking. They occur in the midst of our everyday life and provide opportunities for us to experience something new and gain insights to enrich our perspectives.

Physical Infrastructures lens examples:

- Develop venues for programming that bring people together to share their work and provide exposure to funders or industry collaborators

- Recognize the value of user experience (UX) design for many applications

- Provide support systems to facilitate pop-up events

- Layer on augmented reality information to enrich experiences of campus space and learning

- Make visible and showcase creative, entrepreneurial activities to expose passersby so they can learn as they move through the campus

Incentives and Policies lens examples:

- Provide budget and incentives that bring people together for "discovery experiences"

- Sponsor opportunities for hackathons and events that connect teams with common interests

- Promote experiential learning

- Incentivize student experience with new research directions

Knowledge and Systems lens examples:

- Celebrate and share capstone projects, student research, and student ventures

- Enable data-rich visualizations and interactive display systems to enrich experiences

- Capture and archive moments for asynchronous experience

Planning Principle 5: Process

Foster and celebrate innovative practices and learning at all levels of the organization through encouraging experimentation, design thinking, and prototyping, physically and virtually

Physical Infrastructures lens examples:

- Make prototyping an integral part of the space-planning process and learn at small scale before making larger investments

- Make users aware of "beta" spaces and their design thinking friendly affordances

- Encourage pedagogical experimentation in flexible studio spaces

Incentives and Policies lens examples:

- Cultivate a cycle of testing, assessment, and evidence-based planning at all levels

- Dedicate budget allocation to prototyping and engage stakeholder input in all stages of planning

- Provide support systems — both operational and consultative

- Value organizational learning

Knowledge and Systems lens examples:

- Capture data and analyze findings on effectiveness of prototypes and space uses

- Develop more robust collaborative software capabilities

- Develop IT systems that can respond to change and experimental practices

How Can the Framework Be Implemented?

Sharing a “north star” among a diverse set of efforts is essential for integrated planning to succeed over time.

Using the Innovation Landscape Framework in a design thinking process as a generative tool has the potential to increase the output of ideas, proposed efforts, and initiatives to discuss, prioritizing and integrating them into planning efforts across multiple campus systems. It can also create confidence in the comprehensiveness of the planning process. Concepts could range from tactical "quick wins" to long-term projects that require multiyear capital investments.

Once prioritized for action, individual projects or initiatives need to be carefully defined so that their implementation can be visualized as a series of discrete steps in a process. Each action or target can be planned individually, with unique sets of leadership and stakeholders, while remaining integrated within the larger university-wide effort. The steps in the newly defined process need to be clearly articulated so that physical artifacts or systemic changes are developed in a way that stakeholders can align around them.

Artifacts that demonstrate innovation initiatives might take physical form as prototype spaces, pop-up experiences, or exhibits. They can be thought of as prototypes that instigate and provoke discussion, with the ultimate goal of creating consensus and allowing the implementation of the project to move forward. Sometimes the object of focus might create a new understanding of a project that will require redefining it. The intent is to keep the stakeholders engaged in the process so that each project is resolved in a manner that benefits the health of the larger integrated planning effort.

How Are the Physical Components of the Innovation Landscape Defined?

Planning the physical infrastructure of the Innovation Landscape is important to provide an intentional and distributed network of activity settings and opportunity spaces for people to collaborate, make, invent, and share.

Many components of campus planning can be integrated to support innovation initiatives more effectively. To dig deeper into the framework, we describe aspects of the physical infrastructure lens in more detail, addressing issues of typology, mapping, and layering.

The Innovation Landscape is made up of a hierarchy of types of hubs or nodes. A typology of component types can be developed and adapted for large or small institutions to analyze a campus's existing facilities, to envision a distribution of facilities that have the potential to support or engage, and then to define an enhanced network that reflects the institution's future aspirations. The kinds of questions that need to be addressed are: What are the components of the system? How should they be distributed? What communities do they serve? What activities will happen in them? How will they be managed?

Physical Components: Defining Hub Identity

To plan the Innovation Landscape, each hub or node is distinguished through a range of dimensions.

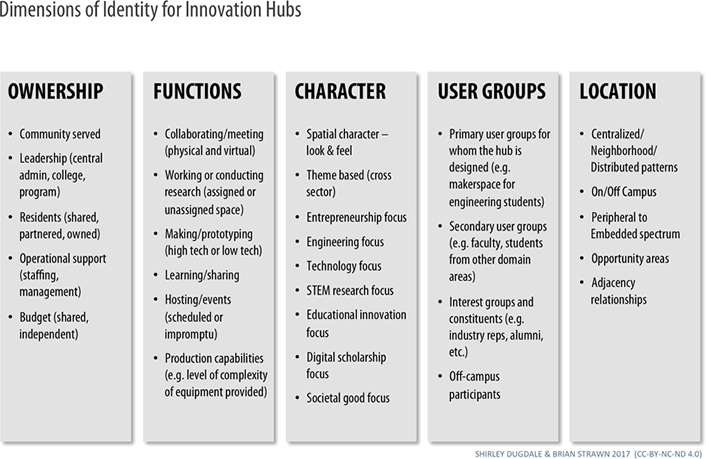

Figure 2 outlines dimensions that define different identities for hubs and gives examples of characteristics. This process of identity definition can help lay the conceptual groundwork for later space programming or intentional expansion of new options within the Innovation Landscape. Some of those include:

- Ownership: those who have vested "ownership" in the success of a facility and responsibility for managing it and building its community (e.g. community-driven or student managed vs. staff or faculty managed)

- Hub Functions: the range of activities and services a hub hosts; the equipment, training, support, and consulting expertise available

- Character: the hub's culture, purpose, look and feel

- User Groups: the users the hub is intended to serve (e.g. range of novice to expert, public to private mix, ease of accessibility)

- Location: the hub's relationship to its context and other components; its visibility within the campus or a building's fabric; exposure to off-campus groups and partners

Figure 2. Factors to consider in analyzing or defining innovation hubs

Physical Components: Designing a Palette of Facility Types

A palette can be developed that responds to the unique situation of each campus, the opportunities available, and institutional strategic goals.

The creation of makerspaces is in its early stages, but as demand matures, maker activities and a culture of prototyping will likely extend across many facilities on campus, each hub developing its own culture as users collaborate. Note that spaces for collaborative making and entrepreneurship can be integrated into many types of facilities — and attention to fostering a community of engaged users will be as important as providing space and equipment. An Innovation Landscape palette outlines a hierarchy of hub types that can be used to plan an integrated network. These might include some of the following models:

- An Innovation Center is the most prominent and centralized type, branded as the primary symbolic center of innovation activity as well as a showcase. Examples include an entrepreneurial co-working center bridging commercial and academic populations, a "garage" incubator of inventive activity and prototyping, a center for technology transfer, or a major research institute.

- District hubs serve a similar function but are associated with a neighborhood or domain area, such as a makerspace for an engineering complex, a device prototyping lab in a health sciences sector, or a digital arts lab in an arts district. They may support coursework or capstone projects.

- Makerspaces encourage the ethos of making and tinkering in a broad range of facility types, from facilities for 3D printing or metal and wood fabrication to electronic tinkering in Fab Labs or digital making in media labs — most combine multiple types of hands-on activity. Learning from peers and mentors helps students develop confidence and skills as they pursue individual and team projects that may be outside of course-related activities. Increasingly, makerspaces are being introduced in libraries, where they are accessible to all students.

- Academic incubators promote innovation in academic affairs, such as teaching and learning centers supporting new directions in pedagogy, or digital scholarship centers encouraging experimentation with applications of multimedia, geospatial systems, or textual analysis.

- Consultation hubs provide valuable services and expertise to help learners and aspiring innovators in many fields, for example offering consultation on intellectual property issues or funding resources for those focused on leveraging inventions or discoveries, or consultation on new directions in digital scholarship or data science.

- Community nodes host local clusters of activity such as specialized learning communities, often self-organized, or student clubs.

- Blended, mixed-use facilities are building types where making and innovation energy infuses the entire facility (such as at the University of Utah's Lassonde Studios, positioned as "a residential community of entrepreneurs, innovators, and creators").

- Corridors can become organizing elements, both interior and exterior, for example displaying a history of institutional innovation or tying together a sequence of places with a common theme of discovery (as celebrated at the University of Minnesota's Wall of Discovery and Scholars' Walk, which honors intellectual achievements as it connects many buildings).

The more hubs can be made accessible to anyone on campus to use regardless of discipline (with appropriate training, of course), the richer their potential and the easier it will be to break down barriers to interdisciplinary teaming over time. Libraries are particularly well positioned to offer makerspaces and consultation hubs: they are often centrally located, operate late hours open to all, and are user-oriented in their services.

Physical Components: Mapping the Innovation Ecosystem

Many different types of innovation-related activities occur on a campus and, because they are part of a complex ecosystem, they can occur in many types of places. By mapping the hubs that exist and their locations, the distribution patterns and their underserved gaps can become clearer. Generic categories for mapping can apply to academic institutions regardless of size.

Mapping can make visible not only the ecosystem of facilities for making with physical and/or digital resources, but also the network of incubator spaces and service points for consulting with experts — which can be important catalysts for cultivating innovation. For example, libraries offer consultation services on research, data management, patent searches, and new applications for academic technologies, as well as incubators for digital humanities, data science, and collaborative workspaces — features that will become increasingly important to support an evolving innovation ecosystem.

It is desirable to conceive of different types of maker environments accessible to all so that everyone on campus can be supported in their creative endeavors. These can be studios or makerspaces for creating or prototyping — which now offer a wealth of 3D printing/scanning, laser cutting, electronics, sewing, and other fabrication tools — but also might be facilities equipped for digital making, such as media labs for production with digital editing and image resources that are all part of emerging digital scholarship.

Providing tailored support services as well as space and equipment is important for success. Space programming needs to take into consideration:

- the makerspace's potential role as an invigorating social hub for a community of learners and/or entrepreneurs, reflecting their culture, values, and aspirations;

- the creative processes that will happen there;

- the kinds of consultation and technology services that should be available;

- desirable types of settings for collaboration and peer learning;

- the types of output users want; and

- the equipment complexity, for both makers and managers.

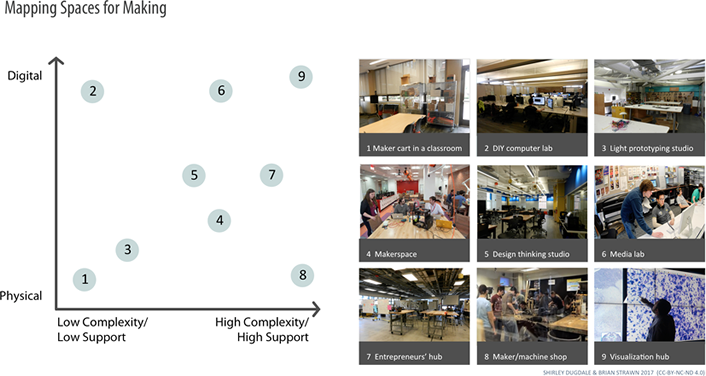

At a campus level different types of places for making can be identified and mapped based on a framework with two dimensions: Physical to Digital, and Low Support/Low Complexity (of equipment and operation) to High Support/High Complexity. Figure 3 illustrates how this framework can be used to map different types of facilities and identify underserved areas.

Figure 3. Mapping diversity in facilities for making3

How Do Virtual Environments Layer onto the Innovation Landscape?

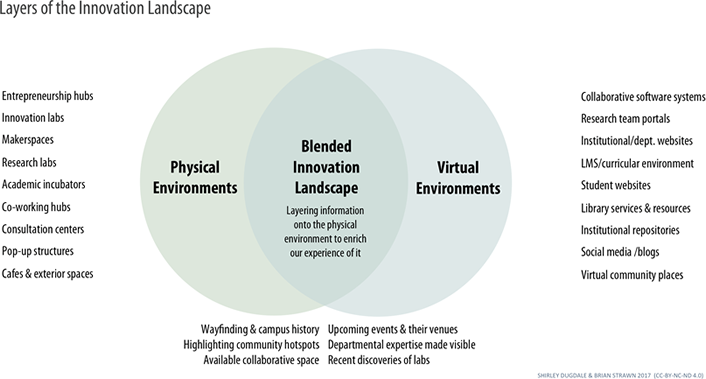

The Innovation Landscape is perceived in terms of both physical and virtual places, but increasingly it will include a hybrid realm layering digital information over our perception of the built environment.

Augmented reality promises to enhance discovery as we experience the physical environment, blending our physical and digital realms. Today augmented reality applications already allow us to interact with physical spaces through mobile or wearable devices and geotagging of physical spaces with information content.

Layering of information onto our perception of the landscape will allow the environment to be even more stimulating, rich with information, and more open to discovery and interaction. Readily available mobile technologies can be used to create a fully interactive environment that exists at the overlap of the physical and digital worlds (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Layering information onto the Innovation Landscape

How Can User Experience Design Inform Integrated Planning for the Innovation Landscape?

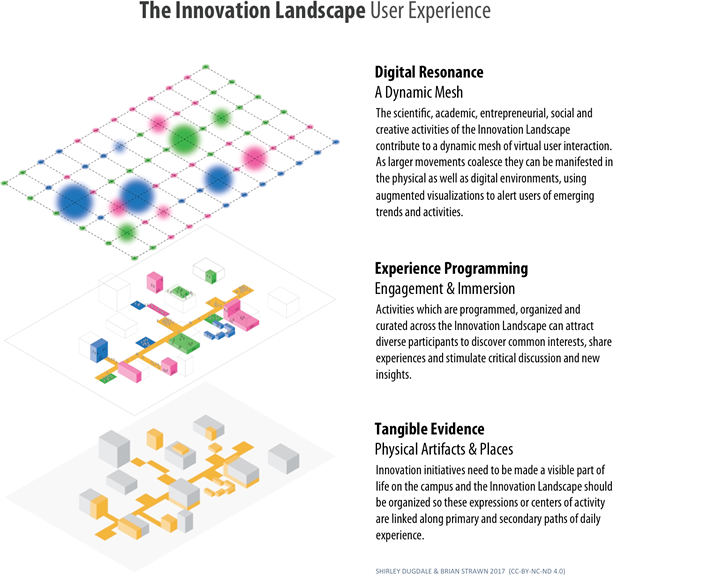

To create effective user experience strategy for an Innovation Landscape, three interrelated aspects must be explored and woven together through integrated planning: tangible evidence, experience programming, and digital resonance. See figure 5.

- Tangible evidence: The complex of physical places, facilities, objects, and artifacts of activity that users observe and experience as they move through a campus and that provides visible evidence of creative energy. The relationships between these physical places and the circulation connectors between them can be planned to expose passersby to different types of collaborative activity and display pride in innovative accomplishments.

- Experience Programming: Programming for events or immersion in activities that are organized and curated across the Innovation Landscape. Programmed events and collaborative gatherings like hackathons can attract diverse participants to discover common interests, share experiences, and stimulate critical discussion and new ideas. The Innovation Landscape can be conceived as the public arena for communicating innovation efforts being cultivated by all colleges/schools and units on a campus and launching pilots, interdisciplinary projects, and entrepreneurial ventures. (Communication and visibility are key: a project being developed between engineering and architecture might be of great interest to a social scientist on campus, but only if the social scientist knows about the effort.) The Innovation Landscape offers shared experiences and opportunities to socialize innovation initiatives among the wider community. Events become a catalyst to bring people together and stimulate dialogue and interaction among learners, colleagues, and visitors; although transitory experiences, they are powerful for developing new relationships and stimulating collaboration.

- Digital resonance: The network of virtual hubs that support innovation acts as a dynamic mesh across the landscape, complementing the physical places in attracting and connecting participants who want to collaborate and innovate. These digital places range from the web presence of entrepreneurial and maker communities, to other communities such as those of research institutes, scholars' networks, institutional and open-source repositories, collaborative software sites (e.g. slack), informal blog sites, and the social media dialogue of students, faculty, researchers, and their colleagues in other locations. Events that blend face-to-face with virtual dialogue such as webcast symposiums and webinars can generate ripples of digital connections and rapidly disseminate knowledge within the innovation ecosystem.

Figure 5. Creating engaging user experience in an Innovation Landscape

The Dynamic Innovation Landscape

A vibrant Innovation Landscape will be immersive, inviting serendipitous experiences with an entrepreneurial spirit as part of daily campus life. It will offer settings that host visible manifestations of creative work and collaborative energy and provide places that are accessible, welcoming, and responsive to a culture of innovation. Diverse participants across an institution should feel drawn to bring their imagination and energy to these places, and they should learn from their experiences in them, whether expressed through physical artifacts, communal experiences, or virtual discourse.

(Note: This article has also been accepted for publication this spring by Planning for Higher Education, the journal of the Society of College and University Planning.)

Notes

- One such framework is the Ten Types of Innovation [https://www.doblin.com/ten-types] developed by the Doblin Group (now part of Deloitte) around 2000. It was published in 2013 in The Ten Types of Innovation by Larry Keeley with Ryan Pikkel, Brian Quinn, and Helen Walters.

- Shirley Dugdale developed the Learning Landscape approach in 2001. It was described in the article "Space Strategies for the New Learning Landscape," EDUCAUSE Review, March/April 2009.

- Images used in figure 3: (1) Lathrop Library classroom, Stanford University; (2) Odegaard Undergraduate Library, University of Washington; (3) d-school, Stanford University; (4) Hill Library, NCSU; (5) BME Design Studio, Johns Hopkins University; (6) Vitale Media Lab, Weigle Information Commons, University of Pennsylvania; (7) Co-Motion, University of Washington; (8) Invention Studio, Georgia Tech; (9) CURVE, Georgia State University Library.

Shirley Dugdale, AIA, is founder of the space strategy consultancy Dugdale Strategy, a co-creator of the ELI Learning Space Rating System, and an advisor to the Learning Spaces Collaboratory.

Brian Strawn is a design planner and co-founder of Strawn + Sierralta.

© 2017 Shirley Dugdale and Brian Strawn. Distribution of this work is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.