Panel members from an EDUCAUSE 2017 Annual Conference session offer insights about the role of provosts and chief academic officers in digital courseware deployment and the challenges of using technology to advance teaching, learning, and student success.

Higher education provosts and chief academic officers (CAOs) have come of age, personally and professionally, with the technologies that are now ubiquitous on campus and in the consumer market. However, considerable survey data and numerous conversations suggest that many provosts and CAOs remain skeptical about the potential or claimed benefits of information technology as a resource for teaching, learning, and instruction. They are also concerned about the significant investments that institutions make to support information technology for those purposes.1

At the EDUCAUSE 2017 Annual Conference, Kenneth C. (Casey) Green moderated a panel discussion with two of the CAOs involved in the Association of Chief Academic Officers (ACAO) Digital Fellows Program and with the principal investigator on the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant that created the year-long program. In this session, the three panel members offered their perspectives on campus IT investments, including what the panelists see as working—and what they see as missing—in instructional technology portfolios today.

The Panelists

Casey Green: Let's begin with quick introductions from each of you, including a brief description of your institution and the CAO/provost's role within it.

Charles Cook: Austin Community College is in Austin, Texas. We have a surface area of five counties—geographically about the size of Connecticut. We have 11 (soon to be 12) campuses, including a shopping mall, which we bought and are converting into the Highland campus, which houses the ACCelerator, a huge lab offering students personalized and adaptive learning opportunities with instructional and coaching support in a number of disciplines. We have about 40,000 credit students and 10,000–12,000 continuing and adult education students—with about 52% white, 34% Hispanic, 7–8% African-American, and 5% Asian.

As the CAO, I try to be the connector. Since the college is geographically spread out, we try to have common communication across the campuses, and across programs, to ensure that we have good quality and good consistency in what we're offering our students. Both student services and academic instruction report to me, so that makes connecting a little easier.

Patricia L. Rogers: Winona State University, established in 1858, is the oldest normal school, or teachers' college, west of the Mississippi. We also have a branch campus in Rochester, Minnesota, and that campus is 100 years old this year. We have approximately 8,100 students, 340 full-time faculty, and 185 part-time faculty. We have about 13% students of color, a number that is rising and that is rather unusual for a small school in southern Minnesota. We offer a range of programs, with nursing and health sciences being our leaders due to our proximity to the Mayo and Gundersen Clinics.

The role of the provost is to stay out of everyone's way. Because I'm a good Minnesotan, I sit in the stern of the canoe and help power things. I put the smart people out front and have them lead the show.

Laura Niesen de Abruna: York College, a private institution founded in 1787, has gone through many iterations. Right now, it has 5,000 students—undergraduate and graduate.

As the provost, I'm the chief academic officer, but I'm also in charge of institutional effectiveness, strategic planning, institutional research, and all technology and instructional design. I wrote and oversee the grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to help CAOs across the United States understand how to deploy digital courseware.

Current Priorities, Emerging Achievements

Green: We've all come of age with desktops, laptops, tablets, the Internet, Wi-Fi, and cell phones. Beginning with the arrival of PCs and Macs on campus in the early 1980s, these technologies have had implications for teaching and learning, both on campus and online. The current term for this seems to be "going digital." What is the meaning of "going digital" at your institution?

Rogers: On our campus, "going digital" used to mean going online, and that's really been changing quite a bit, especially lately. We're looking into all of the various digital technologies and, in particular, adaptive technologies. Certainly, as part of this group of ACAO Digital Fellows who are looking at digital learning and digital teaching and learning, I've really been adding to our portfolio of what "going digital" means on our campus—that is, we're looking not only at gateway courses but also at how we can better serve adult learners, especially those in the graduate studies and those who are at a distance. It's partly online, but really, a lot of this has more to do with enhancing those teaching and learning technologies to better everyone's opportunities.

Niesen de Abruna: The CIO and I started at York College during the same year, and we formed a team called the Data Governance Committee. It's cross-functional. We have student success, academic affairs, and IT organizations represented in the committee. Our role is to provide a digital strategic plan for the institution, and it has worked extremely well so far.

Green: What about ACC's priorities for "going digital" in terms of the size and scope of its service area and student population and how the targets of opportunity are triaged?

Cook: Even though we've made a lot of progress, we still have many skeptics among our faculty and staff and in the community. I think it's very important to talk about why you go digital. "Going digital" has been promulgated for a number of reasons, one of which is to lower costs for students.

Green: Is that working out at ACC?

Cook: Absolutely. “Going digital” has been touted for giving the student greater agency and for personalizing and adapting learning. And I think it holds promise for us to be able to figure out how to improve student learning outcomes and, maybe most importantly, to close equity gaps. And yes, we are reducing costs for students by moving to OER (open educational resources). One of our consultants warned us about the seeming allure of some “open” or “free” digital resources. She said: “OER are touted as free; but they’re free like a puppy. They entail constant care and grooming and ongoing faculty development.” So even though this may not be a way to save money for the institution, I think we're looking to reduce costs for students.

Green: What about cost issues at Winona State? Many campus officials are understandably concerned about the cost of digital courseware.

Rogers: The costs really aren't all that different. In fact, as we all know, initially you're spending a lot more money getting revved up for using digital technologies. What we're finding is that students are now taking advantage of the banded tuition. They're taking those additional courses. They can take the courses online, and they can take classes in a variety of ways to meet different needs. In that sense, we've lowered the cost.

Green: Where has York College been successful in "going digital"?

Niesen de Abruna: We've been successful in introducing a digital strategic plan to the board of trustees; that plan didn't exist until this year. I've been able to say: "I need three things. First, I need software for retention. Then I need software that's going to help me with degree planning. And third, I need software for adaptive personalized learning." The trustees thought all of this was a great idea. For a provost, integrating the digital world into your president's strategic plan is very important.

Green: It sounds like you're at a takeoff point with the new digital plan. Are there successes you can point to in terms of where faculty have already made investments or significant effort?

Niesen de Abruna: Yes. The faculty found out that I had received the grant to start the ACAO Digital Fellows Program, and they decided (on their own) to contact some vendors. They're using ALEKS for mathematics and for chemistry, and they brought it to me. Although I am not an ACAO Digital Fellow, my faculty wanted to introduce digital software on our campus. That's been a very good pilot, and I think it's going to take off.

Vetting Projects

Green: One key challenge facing all CAOs is how to find reliable information to vet faculty or department requests—which are often couched in ecstatic projections about outcomes for everything from classroom learning to degree completion. Where do you go for credible information—either to validate the claims of the advocates or to offset the antagonists who say "this will never work"?

Rogers: I'm blessed with a fabulous Teaching, Learning, and Technology (TLT) group, and the CIO reports to me and also sits on the cabinet, so I get firsthand information from the experts. I have an instructional design background myself, but I'm pretty far out-of-date compared with where our team is right now, so I rely on the team to take a look at requests. I also go to conferences like this (EDUCAUSE) and talk to my peers and talk to the vendors and gain personal knowledge.

Green: Are there third-party sources that any of you refer to as part of your due diligence or validation process when people come to you with suggestions or when you hear about the wonders of a particular instructional widget?

Niesen de Abruna: I go to Courseware in Context (CWiC), which was developed by Tyton Partners in collaboration with the Online Learning Consortium and with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. CWiC has done a lot of the work for small institutions like mine. It has gone through what you might need and what's out there in terms of products and what might work for you. If you don't have a very large institution with a lot of instructional designers—which is my case—that's where I would go to start the conversation with the CIO.

Cook: Luckily, the community college world is very collegial. We share and share alike. Our president/CEO, Richard M. Rhodes, recently became a board member for the League for Innovation in the Community College. At ACC, the president and the provost travel to a different community college each semester to learn what's new and innovative and what best practices the college has uncovered and can share with us. Last spring we went to Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland. We visited its Manufacturing Institute [http://www.themanufacturinginstitute.org/Skills-Certification/Educator-Resources/M-List/State-Profiles/Ohio/Cuyahoga.aspx], which is integrating continuing education, credit, and competency-based approaches in different modes of instruction. This fall we went to Moraine Valley Community College outside of Chicago. MVCC has the Center for Systems Security and Information Assurance (CSSIA), which is one of the first five Centers of Academic Excellence in 2 Year Cyber Security & Information Assurance education (CAE2Y) institutions in the country. So to answer your question, at ACC doing our due diligence is a matter of sharing and keeping in constant contact with our colleagues and friends around the nation.

The CAO's Role

Green: The role of CAOs/provosts varies a good deal depending on the campus size, complexity, mission, and culture. That's also true about their leadership role in different initiatives about the academic enterprise and, in particular, technology. Some CAOs/provosts are very involved, whereas others engage only at the last step. What do you see as the appropriate role of a CAO in the conversation about technology initiatives on the instructional side?

Niesen de Abruna: I think some of the digital courseware that we've been talking about has really come of age in terms of its ability to move the needle on retention. Once you know that, as a CAO you will want to make this one of your top priorities. All CAOs have two or three issues—whether the issue is global awareness or service learning or digital learning—that they want to move forward in the budget and that they want to present to their faculty as a high-impact practice. Digital learning should be one of those issues. For it to become truly embedded in the institution, the provost has to take a personal interest, and it has to be one of the top priorities.

Rogers: Absolutely. The CAO has to be involved in the technology and what's going on in that world. A lot of what I concern myself with—and this is indeed what keeps me up at night—is retention. Our students demand that we pay attention to what it is they need, and these are typically students who have access issues and who need some of the adaptive technologies that we can now use. In fact, the ACAO Digital Fellows Program has been fantastic for me because I didn't realize how many of our faculty were already using adaptive technologies. They intuitively knew that they had to do something to reach their students differently. The fact that this Digital Fellows Program is now folded into our university strategic plan and has been elevated to an institution-wide initiative is exciting for me as a CAO. In a state system, a state university, this is exactly the kind of thing that you hope will happen—that you get this lift from spotlighting faculty work as part of a larger initiative, and things start having a life of their own.

Cook: I would add that the CAO role is also about taking on a cheerleading role and an entrepreneurial role, and it is certainly about gathering resources to funnel in to faculty hands.

Supporting (and Protecting) Faculty

Green: Faculty members are at the heart of the conversation about instructional integration, information technology, and digital learning. For more than thirty years, higher education institutions of all types and sizes have made great proclamations about the critical role of information technology in instruction and the institutional mission. These edicts might come from the president, the provost, or the board or be part of a strategic plan. Yet the trickle-down in terms of resources and support for faculty is minimal, if it exists at all. Although there may be some campus projects and release time, there's no recognition and no reward for the faculty involved. What should the CAO's role be in supporting—and, by extension, protecting—faculty who say: "This is important to me. This is part of my scholarly portfolio. If you want me to do this, I need more than just some release time."

Cook: We have to make this a very high-profile activity for faculty and assure them that it's also a no-risk activity, because it is still so new and much still needs to be learned. And we have to help them find resources. I'm going to brag a little bit here. In October 2017, The Chronicle of Higher Education named 10 faculty members as innovative trailblazers; Amardeep Kahlon, one of our computer science faculty, was the only community college faculty member featured. She was part of a team that received a Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grant from the U.S. Department of Labor to create a completely competency-based education degree in computer programming. We've doubled the number of graduates in computer information technology and are filling a high-demand need for the community of Austin.

Green: What about protection and support for faculty—especially young faculty? Often and disproportionately, younger faculty handle the heavy lifting for departments because, being younger, they're supposed to "do the technology stuff." Yet, when they do it—and I hear this at all types of institutions—they don't get credit for the work in terms of review and promotion. The technology work doesn't count, particularly at four-year colleges and research institutions.2 Young faculty are told: "Wait. Get tenured, get through the hurdle, get over the hump, then do it. Because this will not help your career—even if you're being pressured to be the lead person on a digital learning initiative for your institution."

Rogers: I've heard that this has been going on. It's a little bit of faculty bullying based on assumptions about what is valued or not by university leadership: "Please don't change much. We don't want you to do much." In my institution and in our state system, we have a union with specific criteria for evaluation. At Winona State, we deliberately meet with our faculty on this evaluation criteria issue. We have a panel, consisting of deans and myself, to ensure faculty understand that indeed, these kinds of things count. In fact, the first of the five evaluation criteria is focused on teaching and is weighted a bit more heavily than the other four. We make certain faculty understand that designing their courses to be more accessible through digital technologies and integrating technologies into coursework in other ways will be counted very favorably in the promotion and tenure process, under Criterion One and under other areas that speak to student growth and development. We (the deans and I) have put this pledge – to recognize faculty innovation using technologies to enhance teaching and learning – in writing and in a video, and we've said it publicly.

Niesen de Abruna: I'd like to make an additional point: faculty generally—not just at my institution, but at all institutions—are more than willing to adopt something innovative if you can show them that it's going to increase the quality of learning. Most faculty members have enough intrinsic motivation that they really want to do this kind of work, as long as they don't think it's a fad. If something is going to help their students, they will naturally go to it whether they're in a research institution or a four-year university or a community college.

What I need to do with the CFO is talk about the return on investment. Every time we save a student X number of dollars, that is a real gift to the institution, and the faculty member should be rewarded. At York I've started a group of faculty fellows who are working with digital learning, and they'll get all kinds of rewards for that. I don't think we should underestimate the interest of our faculty in grabbing on to something that they think is going to help their students.

Assessing Outcomes

Green: Based on my national surveys of CIOs and my conversations with campus leaders, I know that barely one-fifth of campuses evaluate their digital initiatives in any formal way—whether that's assessing return on investment, the impact of campus grants on instruction, or the release time given to faculty who are asked to redesign courses.3 Much of what we do continues to be driven by opinion and epiphany as opposed to evidence and efficacy. That said, movement toward more rigorous measurement is under way, as reflected by both Courseware in Context and MERLOT (which I would characterize as "Yelp for higher education curriculum resources"). What are your institutions doing to measure the impact of your digital initiatives?

Cook: We've joined hands with Civitas Learning, an Austin company that has a product called Illume, which gathers data on the success of various interventions. It uses propensity score matching. You can't really do experimental designs in education—or at least do them easily—but this matches students who are taught via a new digital method, say, to a historical group of very similar students who weren't taught in the same way. We've been able to produce data that shows the ACCelerator, in which faculty and students use ALEKS to personalize their individual plans, has been hugely successful. Students make faster and better progress than they do in the traditional classroom. This teaching methodology has also closed equity gaps: our analytics show that our minority males have made large gains.

Rogers: We've decided to start a WSU Digital Faculty Fellows project on our campus, and part of that project includes an evaluation piece: figuring out the best ways to measure success, as well as looking at potential students and understanding what they're searching for. We pride ourselves on data analytics at Winona State. We were one of the original "laptop campuses," and we have continued to innovate—for example, by being early adopters of Power BI to visualize data and trends. We tend to collect data on everything. We have mountains of it, but we've struggled to look at that data and parse that data in a way that makes sense for all campus community members.

That said, we've had breakthroughs in some areas of using technologies for teaching and learning and for analysis of effectiveness. In fact, we tend to run ahead of the national average in those areas. As a part of our e-Warrior Digital Life and Learning Program, we use a 21-point quantitative assessment plan. This includes the EDUCAUSE ECAR student and faculty surveys to help us benchmark nationally. At Winona State, we have historically compared our results with other public MA institutions and have seen very good results on items such as classroom-based technology resources, communication technologies, professional development around the integrated use of technology, and improving student outcomes through technology. On the student items—such as use of laptops, technologies in the classroom, and Wi-Fi—we have strong numbers compared with those of our benchmark group.

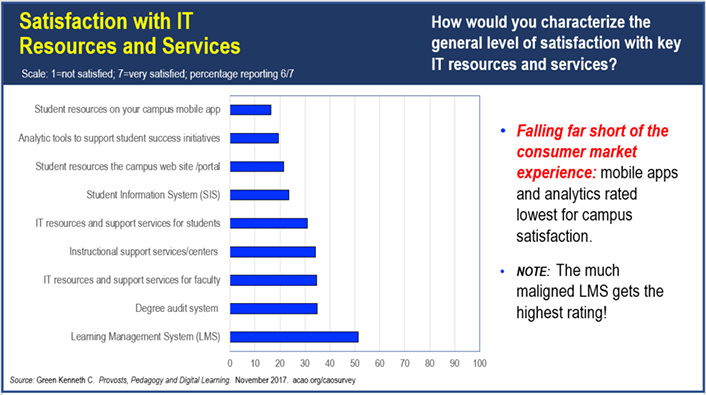

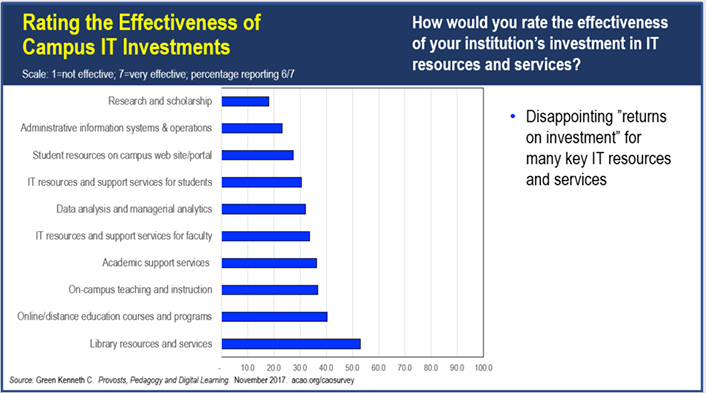

Green: In the last ten years, the conversations about the role and the potential value of analytics have evolved and increased. Yet my own surveys and conversations with presidents, provosts, and CIOs show that analytics in aggregate have been disappointing, at best, in terms of satisfaction with the information gained and investments made. What are we doing well with analytics, and what do we need to do better?

Niesen de Abruna: At York, we're using the analytics that our retention software is giving us. We're able to figure out when students are in trouble, and we have a program that goes out to the advisors and others on the team. We would never have been able to do this without the analytics from the software. In terms of what presidents, provosts, and CIOs are going to be satisfied with, let me give you an example from our campus. We pulled all of the courses and figured out the DFW rate (D-grades, F-grades, Withdrawals). We've found what we call toxic courses or choke courses or the killing field of courses, which tend to be in the STEM fields. We have all of those percentages. We now want to see if digital courseware is changing those percentages. We're seeing that the first couple of experiments have brought those percentages down, so that is some very useful information in terms of efficacy.

Rogers: The other part of analytics involves the intersections, to borrow a term from social justice. It's the intersections of what's going on in the quantitative side and what's going on in the qualitative side: meaning that we look at academic preparation and grades and we measure other factors such as a sense of belonging, persistence, and resiliency. All of those things are starting to be measured alongside of DFW and other aspects. This really is about how we learn.

Cook: Along that same vein, John N. Gardner has talked about the gateway courses, such as English 1301 or History 1301, as presenting major obstacles for student success. Especially in the community college, we are the gateway for thousands and thousands of students of color and low-income students who are disadvantaged in various ways. Gardner explains that when the data of the DFWs from gateway courses is disaggregated, these students are disproportionately represented. If students get a DFW in a course such as U.S. history, their chances of dropping out and not completing go up greatly—even if they are in good academic standing in other courses.4 We have to ask: How are we teaching? What can we do to get better student outcomes?

The CAO–CIO Relationship

Green: Let's talk about the working relationship between CAOs and CIOs. Are you BFFs? Are you collaborators and colleagues? Are you friends, or are you frenemies? What should that relationship be, given the interdependence of responsibilities and institutional priorities?

Cook: A CAO and a CIO have to be best friends. The CAO needs to translate the academic jargon and warn the CIO about the potential obstacles of various activities. On the other side, the CIO needs to translate the technical terminology for those laypeople who aren't immersed in technology every day. Together, they have to recognize what each is contributing, and they need to share that information effectively.

Rogers: The CIO reports to me—a situation that, I'm discovering, is rather unusual. But he also sits on the president's cabinet, and I think that's critical. The president must hear the rich and ongoing conversation between academic affairs and the instructional side of the technology house. It is critical to have both of those voices at the table. The CIO and I share responsibility for academic success.

Niesen de Abruna: I'm reminded of something that EDUCAUSE President and CEO John O'Brien has said: Information technology is not a utility. Sometimes people who are outside of the IT organization think that information technology is about wiring, then about making the campus wireless, and about that sort of thing. But the CIO role has changed. Now the CIO has to be a partner with the CAO. Their joint enterprise is to leverage learning in their community and to work together and translate things for one another, acting as partners in terms of trying to benefit from what's happening in instructional design. It's very exciting for CIOs and CAOs to have that sort of relationship.

The "Aha! Moment"

Green: One final question: what was your "aha! moment" in your career when you understood the value of faculty development and instructional design in higher education?

Niesen de Abruna: The "aha! moment" for me as a provost was becoming familiar with the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) data and the work of George Kuh [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrJPHKL6AH4], the person who started the conversation around high-impact practices. As an academic who had just become a provost, I was dedicated to doing whatever would increase learning. High-impact practices were any sort of active and engaged learning that increased a student's ability to gather more information and to learn more. Digital learning was one of those high-impact practices. As soon as I understood that, I started a center for digital pedagogy at my institution.

Cook: My "aha! moment" was when I began teaching. I started my career teaching in high school. I taught economics for three years and then transitioned to the community college level. From day one, I asked: "How do you do this job, and how do you do it effectively? How do you serve all of your students?" There was never any revelation that came later. Being in the trenches, I recognized that this is where all the action is, this is where we most need to support people. These people—the faculty—are going to make the greatest difference, so we've got to fund them and support them.

Rogers: Building on the importance of faculty, my "aha! moment" also started when I was a faculty member. I had great people who were in the provost role supporting me and letting me move ahead and do some things that were rather edgy at the time. For example, I became a 100% online faculty member while designing our graduate online program during my Fulbright year. Being primarily an online professor at a time when that was unusual—a little bit "out there"—set the stage for my future work with the Minnesota Online initiative. Later, I moved into the dean role and finally into the provost role. I came to realize that those roles are meant to get the nonsense out of the way, to encourage innovation, and to clear obstacles so that faculty can actually do what they need and want to do. This is how colleges and universities advance.

Notes

- Kenneth C. Green, Beginning the Fourth Decade of the "IT Revolution" in Higher Education: Plus Ça Change, EDUCAUSE Review 50, no. 5 (September/October 2015).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Andrew K. Koch, Many Thousands Failed: A Wakeup Call to History Educators, Perspectives on History, May 2017.

Kenneth C. (Casey) Green is Director of The Campus Computing Project, Director of the ACAO Digital Fellows Program, and the moderator of TO A DEGREE, the postsecondary success podcast of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Charles Cook is Executive Vice President and CAO at Austin Community College (ACC).

Laura Niesen de Abruna, the PI on the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant that created the ACAO Digital Fellows Program, is Provost and CAO at York College of Pennsylvania.

Patricia L. Rogers is Executive Vice President and CAO at Winona State University.

EDUCAUSE Review 52, no. 6 (November/December 2017)

© 2017 Kenneth C. (Casey) Green, Charles Cook, Laura Niesen de Abruna, and Patricia L. Rogers. The text of this work is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0 International License.