EDUCAUSE members identify the top higher education information security risks that are a priority for IT leaders today.

For the second year in a row, Information Security is the #1 issue in the EDUCAUSE annual Top 10 IT Issues list. Since 2000, this is the 15th appearance of Information Security, either on its own or layered in with another issue, and the third time it has landed in the top spot (#1 in 2008 as well). While some may debate whether this designation is beneficial or whether it simply brings more scrutiny to campus information security departments,1 there is no doubt about the ongoing risks facing our higher education institutions and the need for strong leadership to help mitigate those risks.2

Starting in 2015, two Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC)3 working groups began to conduct informal polls during their monthly calls to identify the top information security risks on campus. The polls provided HEISC members with the opportunity for more in-depth discussions that often led to the creation of new resources for the broader higher education community. This summer we consolidated the polls and expanded the survey to all six HEISC working groups. Since August 2016, four issues rose to the top of our community's risk poll: (1) phishing and social engineering; (2) end-user awareness, training, and education; (3) limited resources for the information security program (i.e., too much work and not enough time or people); and (4) addressing regulatory requirements.

#1: Phishing and Social Engineering

Phishing—a form of social engineering—is a relentless challenge for institutions. Presidents and board members are just as vulnerable to social engineering attempts as are students, faculty, and staff. Over the past two decades, phishing scams have become more sophisticated and harder to detect. Traditional phishing messages sought access to an end user's institutional access credentials (e.g., username and password). Now ransomware and threats of extortion are common in phishing messages, leaving end users to wonder if they have to actually pay the ransom. Campuses have upped their game by providing online training (e.g., Harvard's IT Academy for IT staff, Texas A&M's Aggie Life and Football Fever games for students), by collecting examples in "phish bowls" to help raise awareness (e.g., Cornell and Brown), and by launching phishing simulation programs to educate end users. This type of self-defense training—teaching end users how to spot and handled phishing messages—is critical to protecting institutional resources.

"We've blanketed our institution with the message to contact our security team with any concerns in an effort to address potential and actual threats from social engineering," said Sharon Pitt, CIO at Binghamton University and HEISC co-chair. "Our security communications team and security leadership have developed targeted communications for specific audiences (e.g., staff with financial authority, faculty, and leadership) regarding our awareness of specific threats and reminders of security practices. We have also developed phishing campaigns to help with student awareness, including giveaways of Goldfish crackers and candy Swedish Fish."

#2: End-User Awareness, Training, and Education

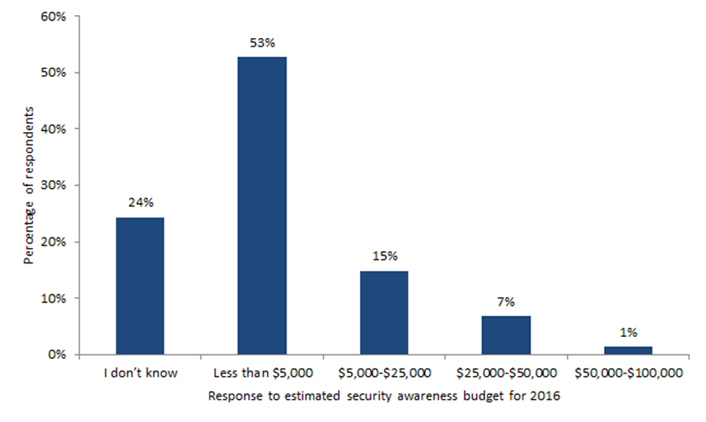

Directly related to the first issue, end-user awareness, training, and education is critical as campuses combat persistent threats and try to make faculty, students, and staff more aware of the current risks. Although the majority of U.S. institutions (74%) require information security training for faculty and staff,4 those programs tend to be leanly staffed with small budgets (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Estimated 2016 Security Awareness Program Budget

Source: Joanna L. Grama and Eden Dahlstrom, Higher Education Information Security Awareness Programs, research bulletin (Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 8, 2016)

"We've established information security awareness and training as a priority, and are aligning resources to address it," said Melissa Woo, vice president for information technology and CIO at Stony Brook University and HEISC co-chair. "It helps that we don't have to reinvent the wheel because both the community and vendors already offer usable solutions."

With limited resources, higher education institutions must be creative and collaborative in addressing information security awareness needs. To help institutions continue to improve end-user security awareness in 2017, the HEISC Awareness and Training Working Group has prepared the Campus Security Awareness Campaign, a framework that includes ready-made content that security professionals and IT communicators can customize and integrate into their information security education communications.

#3: Limited Resources for the Information Security Program

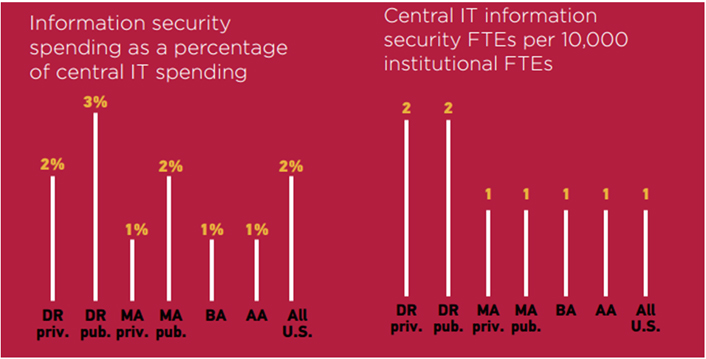

Resource constraints are nothing new to those in higher education, but for an information security department, limited resources can pose an even greater challenge. The 2015 EDUCAUSE Core Data Service survey showed that across all U.S. institutions, about 2 percent of total central IT spending is on information security and that there are 0.1 central IT information security FTEs per 1,000 institutional FTEs.5 Put another way, there is only 1 central IT information security staffer per 10,000 student, faculty, and staff FTEs (see figure 2). Adding to the staffing challenge, security skill sets continue to be among those in short supply in higher education.6

Figure 2. Information Security Spending and Staffing, 2015

Source: Joanna L. Grama and Leah Lang, CDS Spotlight: Information Security, research bulletin (Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 15, 2016)

"Our information security team is a sought-after resource on campus with an ever-growing portfolio of security toolsets to deploy, regulatory compliance assistance, and security awareness engagements," said Cathy Bates, CIO at Appalachian State University. "We have a small team with no immediate ability to add staffing to this area, so we are working to extend our capabilities with graduate assistants and with an information security liaison program across campus. The liaison program supports a two-way working relationship between campus departments and this small team, fostering campus ownership of security responsibilities."

#4: Addressing Regulatory Requirements

The regulatory environment impacting higher education IT systems is complex. Since the United States tends to adopt data-protection laws based on underlying industry (as opposed to one national data-protection law), data elements in higher education IT systems may be protected by a patchwork of different federal and/or state laws. For instance, student data is traditionally protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA), although some types of student data, when it is held in healthcare IT systems, may be protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). In addition, some types of student and institutional employee financial data may be protected by the Gramm Leach Bliley Act (GLBA). State laws may have data-breach notification requirements, and contractual agreements may have their own list of security technological controls that must be implemented and validated in IT systems.

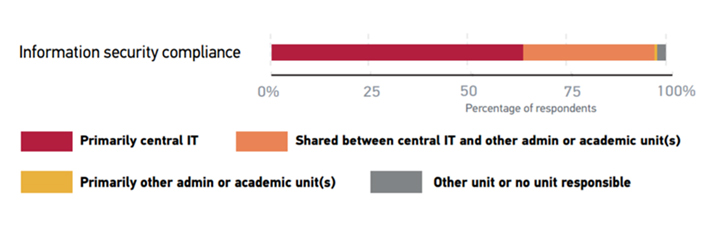

At the center of this pastiche is the information security professional, who must ensure that the institution's IT systems are operated in a way that meets these varied regulatory requirements.7 At many institutions, reviewing and addressing these compliance requirements is a service delivered (for the most part) by central IT units. However, other institutions take a shared approach to meeting information security compliance requirements (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Responsibility for Information Security Practices

Source: Grama and Lang, CDS Spotlight: Information Security

Taking Action

As Information Security lands in the #1 spot on the Top 10 IT Issues list for the second year in a row, it is clear that higher education institutions must continue to improve the maturity of their information security programs to protect their IT systems and data. The EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Initiative offers the following advice to help institutions and IT leaders improve their information security programs:

- Assess the current status of your program using the HEISC Information Security Program Assessment tool. This 101-question assessment tool helps leaders quickly understand the institution's operational information security activities.

- Access the institution's EDUCAUSE Core Data Service results in order to review core metrics on IT services (e.g., information security services) and to benchmark against peer institutions.

- Measure progress on campus-wide information security initiatives by reviewing your EDUCAUSE Benchmarking Service information security capability report.

- Review strategic IT risks with the IT Risk Register, and understand where information security is a risk that could impact institutional business operations.

- Educate those using the ready-made information security awareness content in the 2017 Campus Security Awareness Campaign framework.

- Collaborate and share tips with other information security professionals by participating in the EDUCAUSE security and privacy discussion groups, joining a HEISC working group or committee, or writing a blog post on current security topics.

Information Security is a favorite on the EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues lists, and it is likely that this topic will remain top-of-mind for institutions and IT leaders in the future. As institutional programs respond to and reduce information security risk, IT organizations will be better poised to meet and accomplish their institutional missions.

Notes

- In 2016, four information security leaders debated this very topic. See Joanna Grama, Michael Corn, Sharon Pitt, Neal Fisch, and David Escalante, "Video: 4 IT Leaders Debate Security, Part I," EDUCAUSE Review, October 17, 2016.

- See Cathy Bates et al., Technology in Higher Education: Information Security Leadership (Louisville, CO: ECAR, March 2016).

- HEISC (http://www.educause.edu/security) supports higher education institutions as they improve information security governance, compliance, data protection, and privacy programs. HEISC publishes the Information Security Guide, which features toolkits, case studies, and best practices to help jump-start campus information security initiatives.

- EDUCAUSE 2015 Core Data Service (CDS) survey, CDS Almanac, February 2016.

- Ibid.

- Jeffrey Pomerantz and D. Christopher Brooks, The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape, 2016, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, April 2016). The security management skill set was also listed among the top 10 positions in short supply in Jacqueline Bichsel, Today's Higher Education IT Workforce, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, January 2014).

- Bates et al., Technology in Higher Education: Information Security Leadership.

Joanna Lyn Grama is Director of the Cybersecurity Initiative and the IT GRC Program for EDUCAUSE.

Valerie M. Vogel is senior manager of the cybersecurity program for EDUCAUSE.

© 2017 Joanna Lyn Grama and Valerie M. Vogel. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 52, no. 1 (January/February 2017)