Key Takeaways

- Project-based and team-based assignments provide a richer and more engaging learning environment for students, as explained in this case study of the City of Pittsburgh website redesign.

- The success of such projects depends, to a high degree, on faculty and stakeholder commitment and engagement.

- Applying agile project management principles, including short sprints, complete with planning and review sessions, ensures that student team members stay on track.

- Given the course-limited time between project inception and final delivery, it is critical to identify and use appropriate project management tools.

Creating a framework to engage faculty and students in real-world, client-based projects allows higher education institutions to offer practical educational experiences to their students, as well as to create and leverage strategic partnerships. The University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences has a multidisciplinary faculty and academic curriculum. This allows us not only to contribute to advancing technologies and building systems but also to explore the impact of these technologies on society. Participation in such projects helps our students acquire business, project management, and communication skills in addition to enhancing their technical proficiencies. Furthermore, the emphasis on multidisciplinary projects provides students with experiences that more closely resemble what they will likely encounter after graduation.

We had the opportunity to create a multidisciplinary team of students and advisors to advise the City of Pittsburgh on its website redesign. This case study describes this project, including its learning objectives, deliverables, learning outcomes, and lessons learned.

Benefits of Problem- and Team-based Learning

Problem-based learning (PBL) and team-based learning (TBL) have gained wide acceptance in many educational domains, including medicine, business, engineering, and computer science. If implemented correctly, they can drive the development of critical skills such as presentation, communication, writing, and teamwork.1 PBL also provides a direct gateway for students to apply theory and knowledge presented in traditional didactic lectures to real-world problems.

Another outcome of PBL is the positive effect on student engagement. Because PBL involves collaborative activities with immediate feedback and tangible outcomes, and because it focuses on practical problems with stakeholder engagement and realistic assessments, students find themselves more involved and engaged than with traditional homework assignments or in-class projects.2 A systematic study of students' perceptions of the skills that they developed during PBL projects showed that they do indeed find PBL more engaging than traditional pedagogical methods.3

Few challenges in industry today are solved without a consolidated team effort. The complexity of issues and competitive pressures require a multitude of skills, beyond one person's capability. PBL and TBL assignments allow students to learn how to work collaboratively through issues when the stakes are low, so they can be more effective when the stakes are high.4

Ultimately, project-based assignments help students strengthen their skills in areas beyond technical core competencies. Communicating effectively, learning how to handle objections, resolving conflict, and efficiently solving problems are necessary skills that are replicable across any chosen career.5

Project Description

The City of Pittsburgh has been working on redesigning their website in order to provide the city's employees and businesses with necessary information, attract visitors, and educate citizens on vital issues.

The City of Pittsburgh Innovation and Performance Department (I&P) approached the University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences with a request to collaborate on target audience needs assessment, usability analysis, and benchmarking of the existing website against similar city government websites. Because this project required a wide spectrum of educational backgrounds and skills, we needed to assemble a cross-disciplinary team of students and advisors to analyze the existing site and provide recommendations for the content, structure, user experience, social media integration, management, and content governance. The team consisted of graduate and undergraduate students from programs in Information Sciences (BSIS and MSIS), Library Information Sciences (MLIS), and the College of Business Administration (CBA). This project helped introduce a much-needed framework for interdisciplinary collaboration between schools and departments within the University of Pittsburgh.

The final report for this project provided an analysis of the current website and its users and described our approach to user traffic data, website content, and usability. It also provided insight into the city's social media accounts and how they affect the website traffic. Suggestions also included guidelines for managing the website content and governing the resources within the website management team. Finally, this report offered a perspective on the website's architecture and gave recommendations on how to structure the site's navigation and content to better serve the needs of all users.

Course Goals

As we developed our framework for multidisciplinary team-based projects, we outlined the following broad goals and learning objectives for students in the course:

- Work on all phases and components of a real-world multidisciplinary technology consulting project, from inception to completion

- Experience different professional roles in an interdisciplinary team

- Explore team dynamics and strengthen teaming skills

- Gain hands-on experience with customer interaction and communication

- Become familiar with Agile project management methodologies, including sprint planning and review

- Simplify complex technical concepts for consumption by a nontechnical audience

- Handle conflict successfully and negotiate resolutions

The size and scope of team-based projects, coupled with an aggressive timeline of one semester (14–16 weeks), required a cross-disciplinary team capable of tackling a wide range of issues. The complexity of driving a team of students across such a broad skill set necessitated adhering to a structured timeline with weekly checkpoint meetings, well-documented project plans, and agreed-upon client milestones and deliverables. We also benefitted from an executive client sponsor who actively engaged with students by participating in monthly checkpoint meetings and facilitating client visits as needed. Having an executive client sponsor proved to be a critical component of the overall project's success. The client sponsor could answer questions, address problems quickly, and, most importantly, provide a continuous sounding board for students to brainstorm and finalize their recommendations.

Project Scope

Prior to accepting the proposal from the City of Pittsburgh, we carefully reviewed project requirements and identified the project's scope and deliverables. The goals needed to be feasible for students to complete in one academic semester.

As with any project, managing the scope was one of the biggest challenges. Meeting with the client prior to the project's start and securing up-front commitment on the scope and final deliverables accelerated our execution. Another benefit of meeting with the client prior to project start was that it gave us more time to choose the team members.

Managing the client's expectations, deliverables, and timelines proved challenging for the team, since some students did not have industry experience — their knowledge came from relevant coursework. They were eager to apply their classroom knowledge and often willing to take on more work than specified in the original project agreement. Having a tightly defined scope document helped prevent students from agreeing to more work than they could feasibly achieve in a 14-week period.

Team Selection

We set up the project and advertised it to students as a consulting opportunity, similar to the way companies advertise temporary IT consulting positions. We required students to submit resumes and go through an interview process, allowing us to select the most motivated and the most qualified students.

During the initial team meeting, students self-selected into specialized subgroups based on their knowledge, experience, and skills relative to the critical work areas and overall project scope. Each subgroup was responsible for one or more of the following:

- Data analytics and web analytics

- Content architecture analysis

- Usability analysis — including compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 508 Standards of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)

- User interface analysis — including benchmarking against other city government websites

- Content management and content governance analysis — including a feature-by-feature comparison of content management systems

Data Analytics-Driven Outcomes

Note that analysis of Google Analytics logs of the city's current website provided much needed insight and greatly influenced how students approached the project requirements. The data analytics team used R-Studio to look for visit and browsing patterns, bounce rates, sources of website traffic, user searches, and device usage.

Initial device usage analysis showed that most users access the city's website using desktop and laptop browsers rather than mobile devices. The user experience (UX) team followed this analysis with a usability study and user interviews, which resulted in a series of recommendations regarding a mobile version of the website.

A social media traffic analysis showed that few people access the city's website from sites such as Facebook, Twitter, or TripAdvisor. Those who are redirected from social media sites tend not to spend a lot of time on the website (high bounce rate). This insight, coupled with user interviews, allowed us to offer recommendations to improve social media integration.

Another important insight came from an analysis of search terms. For example, users who were trying to find garbage pickup times searched for the term "garbage pickup." The section on the website that provided details on the subject was titled "Refuse pickup." A follow-up study showed that more than half of interviewed users were not familiar with the term "refuse."

Staying tightly linked to the analytics approach allowed us to quantify and strengthen the final set of recommendations provided.

Project Management and Communication Tools

Given that some students lacked industry experience and had never worked on team-based projects, we felt that it was critical to provide real-time feedback and guidance without the appearance of micromanagement.

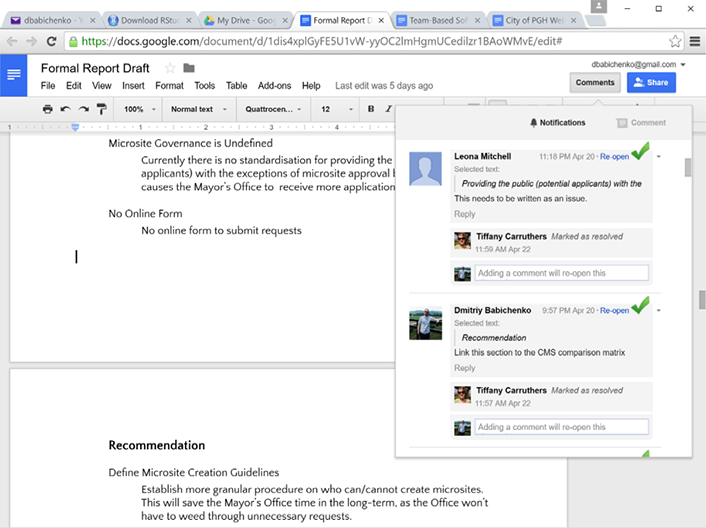

To manage the project's documents, tasks, and communications, we utilized Basecamp Project Management software and Google Drive. Basecamp lets teams share documents and assign, track, and manage tasks. Basecamp's full integration with Google Drive, Google's cloud-based collaborative document editing environment, helped us monitor students' work and provide instant feedback (figure 1).

Figure 1. Google doc for the project

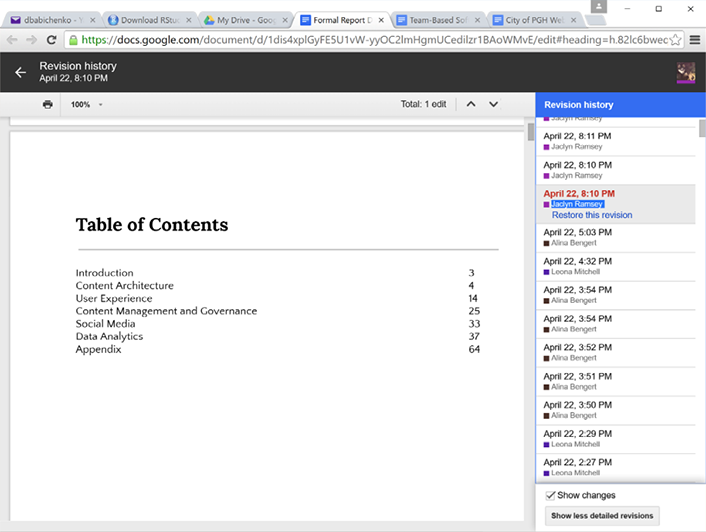

Google Docs' change-tracking feature allowed us to monitor students' participation and contributions, as well as roll back any unwanted or erroneous changes (figure 2).

Figure 2.Google doc with reversion to earlier draft

Because of travel distances to campus and variability in class and work schedules, we could not expect students and stakeholders to attend every weekly meeting in person. To mitigate this and to ensure constant participation, we relied on Skype videoconferencing software for synchronous communication with stakeholders and Google Hangouts for internal team communications. Both videoconferencing tools are available free from Microsoft and Google, respectively — we specifically selected them for their availability across all major platforms.

Student Assessment

We assessed students' performance and graded them based on the following criteria:

- Overall quality of work, both individual and as part of a team

- Stakeholder feedback

- Professionalism

- Quality of writing (requirements documents, technical and user documentation)

- User interface (UI) design and user experience (UX) design

- Final product presentation

- Peer reviews

Reflections

At the end of the project, we conducted a set of exit interviews with stakeholders and students. We wanted this additional insight to continue to provide challenging projects and positive learning experiences for students.

What Worked

Students remained highly motivated and engaged throughout the project. They quickly determined how best to work together to produce an on-time quality deliverable. They were motivated primarily by three factors:

- Students knew that working on a high-impact, highly visible project would enrich their CVs and increase their chances of securing a better job.

- Working with students outside their discipline allowed them to broaden their skills beyond their core capabilities, giving them breadth as well as depth.

- Peer influence not only provided a positive support system but also introduced a competitive standard that students needed to meet weekly.

Students who had prior work experience, or who had participated in other team-based projects, were able to step into leadership roles and provide guidance to their less experienced peers. This established a sense of camaraderie among the students. As unanticipated and difficult issues arose, they felt more comfortable attacking the problem together and brainstorming the best approach.

Meeting weekly with students was critical not only to ensuring the project stayed on track but also in setting the expectations for quality of work. Having to come well-prepared to a weekly meeting and share work outcomes prevented the creation of a bifurcated team of "slackers" and "workers." Though skill sets and levels differed, work effort and output remained consistent across team members.

Finally, having students present their recommendations in a formal debriefing with the chief performance and innovation officer and her team was an invaluable experience, giving them a first-hand view of how experienced leaders think critically, prioritize issues, and make on-the-spot decisions. Having an executive sponsor definitely helped reinforce our efforts and successfully steer students toward making recommendations that would be implementable and workable for stakeholders.

What Didn't Work

Managing a team of eight students introduced an unnecessary level of complexity that sometimes impeded our ability to be flexible. We had duplicate skills in certain areas, so a team of five or six students would have been more practical.

As in any large project, competing factors can affect not only how you approach issues and tasks but also how you engage with stakeholders and what final recommendations you propose to the client. Navigating through these situations is never easy, especially with condensed timelines and students participating in the project who haven't yet acquired the necessary skills to work through a political climate. Again, a smaller team would have made it easier for us to lead students through these issues.

Running a team-based project over a 14-week semester let us offer a complex project that provided students with a rich experience. However, the unfortunate downside is that the crucial work effort coincided with final exams, adding even more pressure to an already intense situation. Some students struggled with the added pressure to the point that it negatively affected their final performance. Though competing priorities are part of the real-world experience, we believe our responsibility as faculty is to give students an opportunity to work in a supportive environment. Therefore, to avoid this situation in the future we plan to take the following actions:

- Build and adhere to a schedule where final deliverables (oral and written) are due in week 12 and use the final two weeks of the semester for lessons learned

- Better set expectations with students up-front as to the workload requirements in the final weeks of the semester

Recommendations

Throughout the course of this study we found scope management by far the most important task for the supervising faculty. All participating parties must agree on the scope, timeline, and deliverables prior to the start of an academic semester. In most cases students do not have the background or experience necessary to identify and commit to a realistic set of deliverables. Without close supervision, students tend to take on more work than they can reasonably complete.

Constant faculty involvement is another key to success. Applying agile project management principles allows faculty to frequently review students' work, provide timely feedback, reassign work, or simply offer the students better or alternative approaches to solving problems. In our case, we borrowed the "sprint" artifact from agile product development — a predefined period of time during which agreed-upon tasks must be completed and ready for review.6 One-week sprints, complete with planning and review sessions, helped keep students on track with tasks and deliverables.

Last, but not least, stakeholder involvement is vital. Projects such as this one should always involve a written stakeholder agreement that outlines a communication plan between the team and the client, as well as an agreed-upon schedule of meetings. The project team must stick to the communication and meeting plans to ensure that the final product will meet the stakeholders' expectations.

Acknowledgments

While we take full responsibility for any errors and shortcomings of this article, we would like to thank Debra Lam, City of Pittsburgh Chief Innovation & Performance Officer; Laura Meixell, City of Pittsburgh Analytics and Strategy Manager; and Smyth Welton, Danelle Jones, and Eric Miazga, City of Pittsburgh's Webmasters for offering our students the opportunity to work on this project. We also thank the University of Pittsburgh students who worked incredibly hard and did an amazing job on this project: Jaclyn Ramsey (MSIS), Tyler Brooks (MSIS), Alina Bengert (MSIS), Jacob Brintzenhoff (MLIS), Flory Gessner (MLIS), Eric Meisberger (MLIS), Bradley Smertz (CBA), Andrew Garfinkel (CBA), and Tiffany Carruthers (BSIS). Finally, thanks to Rachel Kelly, professional writer at the University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences, for providing copyediting assistance.

Notes

- Deborah E. Allen, Richard S. Donham, and Stephen A. Bernhardt, "Problem-Based Learning," New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Vol. 2011, No. 128 (Winter 2011): 21–29.

- Ibid.

- Jacqueline Murray and Alastair Summerlee, "The Impact of Problem-based Learning in an Interdisciplinary First-Year Program on Student Learning Behaviour," Canadian Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 37, No. 3 (2007): 87–107.

- Kenneth A. Bruffee, Collaborative Learning: Higher Education, Interdependence, and the Authority of Knowledge (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1999).

- Carol L. Colbeck, Susan E. Campbell, and Stefani A. Bjorklund, "Grouping in the Dark: What College Students Learn from Group Projects," Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 71, No. 1 (January/February 2000): 60–83.

- Henry O'Brien, Agile: Agile Project Management, A QuickStart Beginners' Guide To Mastering Agile Project Management, 1st ed. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015).

Leona Mitchell is visiting professor of Practice, School of Information Sciences, University of Pittsburgh.

Dmitriy Babichenko is professor of Practice and Project Director, Learning Technologies Lab, School of Information Sciences, University of Pittsburgh.

© 2016 Leona Mitchell and Dmitriy Babichenko. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.