Key Takeaways

- IT leaders benefit substantially from listening to and partnering with their business managers.

- Discussions with business managers from different institutions yielded 10 key concepts they want their IT colleagues to understand.

- In addition to taking this advice to heart, consider using it as an opportunity to open a new conversation with the business managers on your campus.

Partnerships between technology managers and business managers are critical to the success of higher education IT organizations. The expertise in budgeting, financial planning, human resources, and institutional administration that business managers bring to the table can easily be the difference between a highly successful IT organization and one that finds itself mired in institutional processes, unable to meet key objectives.

Talking with Business Managers

Fortunately, the business managers who support IT organizations want to see those organizations succeed and make deep contributions to their institution's teaching, research, and service missions. In a series of interviews, business managers from the University of Washington, Muhlenberg College, and the University of Notre Dame offered 10 critical pieces of knowledge about institutional business operations that they consider critical success factors for technology managers. Let's take a look at the 10 things that your business manager wishes you knew.

1. Information technology is a small part of the bigger institutional picture.

While IT leaders might spend the vast majority of our days thinking about information technology, it's only one piece of the puzzle from the perspective of institutional business managers. The finance and budgeting professionals we work with must balance the financial demands of student financial aid, payroll, construction initiatives, campus services, and many other initiatives competing for scarce resources.

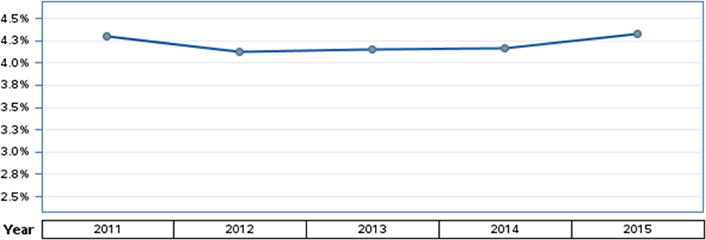

Over the past five years, IT spending as a percentage of total institutional expenditures has hovered between 4.0 and 4.5 percent, according to responses from all eligible institutions in the EDUCAUSE Core Data Service (see figure 1). That's certainly a significant amount of money, but it's only a small fraction of the institutional budget that business managers administer each year.

Source: EDUCAUSE Core Data Service

Figure 1. Central IT spending as a percentage of institutional spending: 2011–2015

"IT leaders need to think strategically about financial issues," said Andrea Amoni, manager of IT Financial Services at the University of Notre Dame. "You need to understand how your single project fits into the broader picture within IT and the institution as a whole. Everyone's default is to worry about their own piece of the pie," she continued. "That is understandable because someone needs to advocate for each group, but IT leaders can't operate in a vacuum."

2. Frame budget requests within your institutional context.

While institutions of higher education all share a common high-level mission, they differ greatly in how they approach teaching, research, and service. Each institution has different priorities and strategic objectives, and IT leaders must understand those differentiators and use them to frame budget requests.

"The key to a successful budget request is less about a pretty presentation and more about showing a solid business rationale that has been vetted thoroughly," explained Trent Grocock, senior director for Budget and Financial Planning at Notre Dame. "Treat everyone involved in the process as a partner and look for ways that you can reallocate existing budgets before asking for new money."

Allan Chen, CIO at Muhlenberg College, understands this balance and believes it applies at institutions of all sizes. "At a smaller institution, every initiative must count," Chen said. "We look at how everything we do impacts student learning and instructional technology. These are the efforts that have the greatest impact on student retention, which in turn leads to stability of our tuition-dependent operating budget."

3. Plan ahead when making significant budget requests.

Institutional budget planning cycles often operate two or three years ahead of spending. The overall institution budget typically requires board-level approval and must be finalized as early as six months before the beginning of the fiscal year. That doesn't leave a lot of time for last-minute additions. Anything showing up outside the normal cycle will have a dramatically lower chance of success, according to Amoni.

"The most important advice I can offer IT managers is to know the timelines and processes at your institution," said Amoni. "If you bring a budget request at the right time, things will be much easier. We hurt ourselves when we bring forward last-minute requests or don't follow the correct request procedures."

Prior planning isn't just for future requests, either, added Grocock. It also applies to unexpected events that may have a financial impact. "Accountants don't like surprises," he cautioned. Communicating with business managers about potentially significant activities as far in advance as possible will help soften the blow of bad news and allow time for the institution to plan appropriately.

4. People are our greatest investment — literally!

IT teams consist of skilled, well-compensated knowledge workers who deliver exceptional service to an institution's students, faculty, and staff. Effective delivery of technology services requires highly effective and engaged teams. For this reason, most IT leaders agree that skilled technologists are the most important asset they need to meet the institution's objectives.

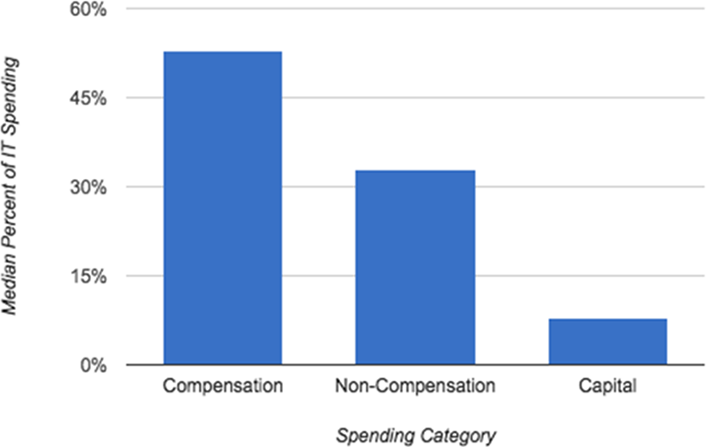

At the same time, it's important to remember that the old adage "people are our greatest investment" is true in more than one way. In a typical IT organization, spending on salaries often outpaces both non-salary and capital expenditures combined. Figure 2 shows data from the 2015 EDUCAUSE Core Data Service demonstrating that the median institution spends 53 percent of its budget on compensation while dedicating only 33 percent to non-compensation operating costs and 8 percent to capital expenditures.

Source: EDUCAUSE Core Data Service

Figure 2. Compensation, non-compensation, and capital expenses as a percentage of total IT spending: 2015 (Chart contains median values across all institutions causing the percentages to not sum to 100 percent.)

Any business manager seeking to gain a solid understanding of IT spending must remember this. "Managers should keep the entire workflow in mind when looking at processes and services. Something that may appear to save on the front end could end up costing more in labor on the back-end because of the mechanics of the process or the number of people that it involves," shared Amy Stutesman, IT business manager at the University of Washington Bothell. IT managers should consider that labor is often more expensive than operations and that it's critical to include time spent throughout the institution as a real cost.

Along these same lines, institutions should think carefully about how they fill IT positions, advised Notre Dame's Grocock. "IT managers should carefully review their open positions and ask whether they really need to fill each one," he said, pointing to a trend toward position nationalization where all open positions revert to a senior level of leadership, where the decision might be made to reallocate those resources to a more pressing institutional need.

As Grocock pointed out, "You also can't underestimate the impact of benefit costs in personnel decisions." While some institutions fund benefits centrally in a way that is invisible to IT managers, those costs can have a real impact on the institution's bottom line. "IT managers should consider benefit costs and may use that information to decide that the institution would benefit from using contractors to perform some duties, especially when they are temporary in nature," Grocock added.

5. Get your numbers straight!

Business managers spend their days dealing with the black-and-white world of budgets and expenses. One of their greatest frustrations, according to Grocock, is when IT managers bring forward a proposal with inaccurate and unvetted numbers because they brought financial professionals in too late in the process, if at all. "We want to be your partner, not a hindrance to your efforts," explained Grocock. "Get us involved early in the process and let us help you build your financial plan. We can help you make sure that you're including all of the costs of an initiative." That advice might sound familiar to IT professionals, who often make the same request of our own campus partners.

When you're pulling together funding from a variety of different sources on campus, "get it in writing," Grocock advised. "When you bring a funding proposal forward, make it clear who will pay for each component." If a project comes with a revenue stream, make sure to include that in your budget estimates, but "be conservative about your revenue projections, " Grocock cautions. "Remember that you're going to need to meet those projections for the project to succeed financially."

6. Money comes in many different flavors.

Every institution handles budgeting differently. IT managers should understand their institution's approach to shifting funds between different priorities. At one extreme, some institutions strictly segregate salary, non-salary, and capital expenditures and do not allow any shifting of money between those budgets. Institutions at the other extreme, however, allow money to freely flow between these budgets. Most institutions lie somewhere along that spectrum and have their own idiosyncratic rules about the "flavors of money."

"We have very rigid lines between our different budgets," explained Muhlenberg's Chen. "For example, we can only use our capital budget for fixed assets. This causes us issues when we consider shifting our spending from on-premises data centers to the cloud. We can't simply reallocate money from capital to operational expenses and must go through a new budgeting process."

In some cases, particularly at public institutions, this inability to reallocate funds ties back to compliance issues. "Our budget is composed of many different types of funds that have different restrictions attached," observed UW Bothell's Stutesman. "People should understand that they can't add new permanent costs when they only have one-time funds."

Another area where IT managers commonly get tripped up involves the difference between one-time and recurring funds, according to Stutesman. It's often easier to find one-time funds for a project and more difficult to cover related recurring costs. "People don't understand that they can't add new permanent costs when they only have one-time funds," she said. Notre Dame's Grocock agreed, saying that "IT managers must be sure to include all costs in their proposals, not just the one-time expenses."

7. Deficits are bad, but that doesn't mean surpluses are good.

Managing a budget is a difficult balancing act that requires discipline, careful monitoring, and wise forecasting. Most IT managers know that exceeding their budget may have dramatic repercussions for the IT organization and, depending on the magnitude of the issue, the broader institution.

Muhlenberg's Chen agreed with this sentiment. He gives the same advice to every IT manager with budgetary responsibilities in his organization: "Whatever you do, don't go over budget. The money does not exist, and we will need to reallocate it from somewhere else. Let me know as early as possible when you experience challenges so that we can adjust. Our budget flexibility goes down as the fiscal year draws to an end."

While it's certainly true that running a budget deficit is a bad idea, it's also important that IT managers realize that large surpluses also harm the organization. Building an excessive budget cushion results in opportunity costs because funds that the institution allocated for technology enhancements sit fallow rather than supporting the institution's teaching and research missions. Notre Dame's Amoni underscored this, saying, "While you can't overspend your budget, you also must be careful not to hoard funds. Large surpluses can damage confidence in your ability to fulfill current operational initiatives and impede the approval of new funding requests."

Finally, IT managers who find themselves in a situation where it is difficult to forecast and manage their revenue and expenses shouldn't hesitate to turn to their business managers for advice and assistance. UW Bothell's Stutesman advised managers to "Keep your budget manager in the loop about where you are with your budget and the risks that you face. One of my roles is providing strategic budget advice. If I see a potential cost overrun, I need to inform the leadership team and find ways we can cut expenses elsewhere to cover it."

8. Cost avoidance and cost savings are not the same thing.

One of the main problems business managers see in the financial components of proposals offered by IT managers is a confusion between cost avoidance and cost savings. Cost savings occur when money budgeted for one purpose is no longer needed for that purpose due to a change in strategy, vendor negotiations, or other measures. When a project realizes cost savings, that results in real money that may then be reallocated for other purposes.

Cost avoidance, on the other hand, occurs when managers take actions that prevent the organization from incurring an unbudgeted cost. Cost avoidance is still clearly a desirable strategy, but with a key difference — cost avoidance is about saving money that doesn't currently exist and, therefore, is not available for reallocation.

For example, imagine an IT organization that currently maintains a storage environment for campus users that has a $50,000 annual budget for maintenance, upgrade, and replacement. That budget supports the ongoing operation of the storage environment but does not provide any room for growth. As storage use increases on campus, IT leaders may find the need to double the capacity of that environment but lack the budget required to fund an expansion of the existing environment.

If IT leaders can negotiate with the vendor to double the size of their $50,000 environment without increasing the annual costs, that results in $50,000 of annual cost avoidance because increasing the size of the environment would have required an increase in funding that did not exist. The $50,000 in cost avoided by this negotiation was never in the IT budget, so it is not available for other uses.

On the other hand, IT managers may decide that they will move the entire storage environment to a cloud-based service that offers complementary use for higher education institutions. Assuming they can support the environment without any other increases in cost, they can then eliminate the $50,000 annual budget for maintenance, upgrades, and replacement. That $50,000 is cost savings that can be reallocated for other uses.

Grocock offered a word of caution to IT managers about using the right language around cost savings. "If you talk about cost savings, be prepared for a corresponding budget cut," he warned. Institutional leadership might thank you for the cost savings and decide to reallocate those funds to a higher institutional priority outside the IT organization. If IT leaders overestimate cost savings, they might find themselves in an unfortunate budget situation when they fail to meet their projections and no longer have the funding to properly support a critical IT service.

9. Build a plan for recurring maintenance, upgrade, and replacement costs.

One of the most common budgetary issues facing IT managers is planning for the replacement of the networks, data centers, servers, and other infrastructure they manage for the campus community. Amoni feels that planning ahead in this area is one of the key partnerships between technologists and business managers. "Don't wait for things to break. Make sure that you have a plan for replacing equipment that provides details down to the department, unit, and building level," Amoni advised.

You also can't expect costs to remain constant from year to year, pointed out Muhlenberg's Chen. "Remember to include price escalators in your plan," he recommended. "Generally speaking, software maintenance fees increase by 5 percent each year, and you need to include those increases in your projections. Along those same lines, read contracts carefully and make sure that you understand how prices will change over time and what happens when the contract term ends."

Chen also shared a cautionary tale about his work at a prior institution that built a new server farm one year with a one-time capital investment. "That created a huge bubble in our budget several years later when we couldn't afford to replace all of the equipment at once," he explained. "We wound up having to operate equipment longer than we would have liked to spread the replacement costs over several years."

UW Bothell's Stutesman offered similar advice. "You really want to stagger the purchase of new equipment so that it doesn't all fail at the same time," she said. "Look a few years out and use historical costs to help project future expenses." In the cases of critical equipment, such as routers and servers, most IT organizations look to proactively replace equipment as it reaches the end of its useful life, making it easy to forecast costs. In other cases, such as edge switches, wireless access points, and printers, "We might choose to run the equipment until it breaks," said Stutesman. This makes cost planning more difficult, and historical data becomes a more important data source.

Doug Kroll, senior director for IT Administration at Notre Dame, pointed out that this planning must take human resources into account as well. "When you put together a maintenance plan, make sure that you have the time and people to actually do the work that you're budgeting."

10. Finance professionals get the same glassy-eyed response to technology that IT professionals get to finance.

Technology leaders often find the world of budgeting and financial management confusing territory loaded with terminology and business processes that seem foreign. It's important to remember that business managers often feel the same way about technology.

According to Amoni, "Finance professionals get glassy eyes when technologists start talking about technology." The mark of a strong IT manager is the ability to keep one foot in the world of technology and the other in the world of business. "Bridging that gap is really important," she said. "If you help us understand the technology, we can help you build a business case and explain it in terms that other university leaders will understand."

In fact, IT leaders can also use these differences as an advantage by asking their business managers to help represent technology projects to others in the institution. "We might not always come from a technical background, but we do understand the functional perspective," pointed out Stutesman. IT managers should use their business managers as liaisons to their counterparts elsewhere at the institution. Stutesman said that business managers are more than willing to play this important role: "I can help you 'administratorize' things. That's what I do best!"

Listen to Your Business Manager!

The advice offered by these business managers is sound and applies on almost any college or university campus. In addition to taking their advice to heart, consider using it as an opportunity to open a new conversation with the business managers on your campus. Find out what they'd add to this list!

For More Information

- Core Data Service Publications, Benchmarking Report and Almanacs

- EDUCAUSE Core Data Service 2015 Almanacs

Acknowledgment

The material presented in this article was originally presented as part of the 2016 EDUCAUSE Management Institute program.

Mike Chapple is senior director of IT Service Delivery and concurrent assistant professor in Computing and Digital Technologies at the University of Notre Dame.

© 2016 Mike Chapple. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0 International.