By appreciating and welcoming various generations into higher education IT organizations, we can both mentor and learn from one another while looking to the workforce of the future.

This article is drawn from the recent research by the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) on the evolving IT workforce needed to support contemporary models of IT service delivery and the emerging world of analytics. The research provides a general picture of the state of the IT workforce, as well as explores the roles, competencies, and career trajectories of incumbent (and aspiring) senior-most leaders in information technology, security and privacy, data, and IT architecture. The research will define professional competencies and lay the foundation for tools that can guide professional development and career planning.

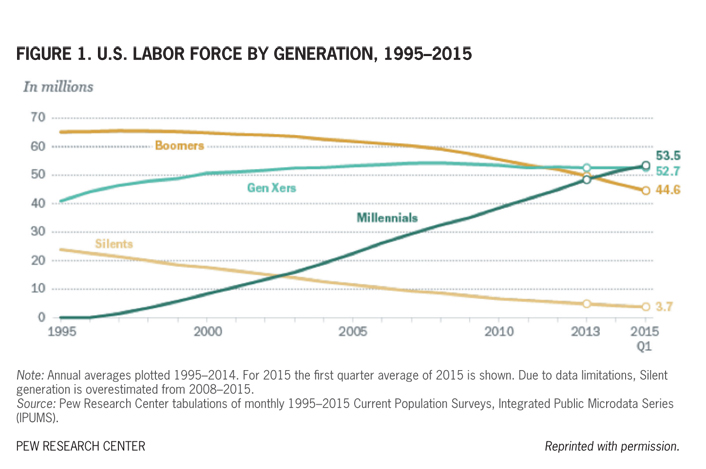

According to a study published last year by the Pew Research Center, the United States recently passed a milestone in the U.S. workforce: there are now more Millennials in the workforce than any other generational group (see figure 1).1 Millennials were born between 1981 and about 1997, Generation Xers were born between 1965 and 1980, and Baby Boomers were born between 1946 and 1964.2 The youngest members of the Millennial Generation are just now entering the workforce, and the oldest members are growing their careers. The youngest Boomers are in their peak productivity and wage-earning years, whereas the oldest members are retiring from the workforce. Gen Xers are situated firmly in the middle.

Why do generational cohorts matter?3 After all, they are stereotypical characteristics attributed to a group of people who happen to be born within about twenty years of one another. Like most other stereotypes, these cohorts tend to be based on a sliver of truth, and from a practical perspective, the oversimplified generalization of traits allows us to create mental shortcuts and categorize an otherwise complex world. To use my own example, I am a Gen Xer, and I have eight direct reports: two are firmly defined as Millennials, two are on the Millennial-Gen X cusp, and the remaining four are entrenched Gen Xers. I report to a Boomer. I interact with all three generations on a daily basis, as do most of you reading this article. Understanding a little bit about the core work-related values of a multigenerational workforce can help optimize the work environment, leverage natural generational attributes, and maximize productivity. In addition, we can't stop the hands of time: all of us will move on in our career paths and will eventually retire to enjoy our golden years. One day a Millennial will have my job, and presuming stability of the position, a Post-Millennial will have the job after that.

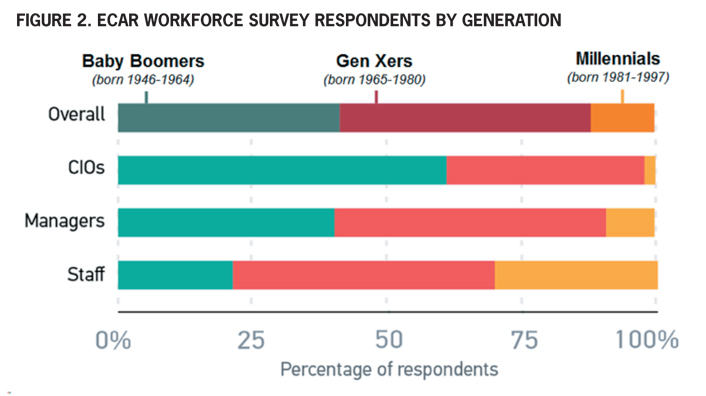

As more and more Millennials are integrated into higher education work teams, an understanding by Gen Xers and Boomers of the next generation of IT workers and leaders—and Millennials' understanding of the current generations—will help colleges and universities maintain business continuity during the generational transition. Millennials bring a fresh perspective to the table. Their youth can infuse energy into teams, and their lack of entrenchment in the ways things have always been done can help others embrace transformative innovation opportunities. In the first quarter of 2015, the overall U.S. labor force was composed of 34 percent Millennials, 34 percent Gen Xers, and 29 percent Boomers.4 For comparison, the recent survey by the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) reported 12 percent Millennial respondents, 47 percent Gen X respondents, and 41 percent Boomer respondents (see figure 2).5 Either ECAR surveys don't appeal to Millennials or there is an underrepresentation of Millennials in the higher education IT workforce. A recent Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA) study, Managing the Multigenerational Workforce, points to the latter. Only 19 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds in that study say they are interested in an IT career.6 This isn't very promising for members of the higher education IT community, who will need to backfill positions vacated by retiring Boomers and career-building Gen Xers.

For the Millennials who are part of the higher education IT workforce, a smaller percentage (44%) report that working in higher education (as opposed to another industry, business, or sector) is very important, compared with their Gen X (51%) and Boomer (55%) counterparts. It is possible that this is a function of Millennials' age (e.g., still exploring career opportunities) or their lack of years in the workplace (e.g., not yet vested in the stability value-proposition that typically comes with higher education careers). Or it could be an indicator that the things Millennials value aren't well represented in higher education IT workforce jobs. Millennials are ambitious and entrepreneurial—Mark Zuckerberg is their peer, after all. Millennials want work/life/community balance: they work to live, they want their work to be meaningful, and they want to be acknowledged for their successes.7 How well do we foster these ambitions among members of our workforce, and how much flexibility do we have at our institutions to better do so? Whereas some managers and some institutions are better than others at creating a work environment that appeals to Millennials, higher education could undoubtedly do more to attract and retain a Millennial workforce. External factors also pose challenges to attracting young talent to the higher education workforce. Economic circumstances may have tarnished the nobility of higher education for young professionals. Careers in higher education might be particularly unattractive to a generation burdened with student loan debt and joblessness (or underemployment).

The recent ECAR survey took a closer look at the higher education IT workforce by generation. More than one in four (26%) of the Millennials who participated in the ECAR workforce survey said that they "probably will or definitely will" seek employment outside of their institution in 2016. This was higher than Gen X IT staff (22%) and much higher than Boomer IT staff (17%). Regardless of whether or not Millennial IT staff are planning to stay or go in the next year, the following five aspects are most important for keeping them at their current institution:

- Quality of life

- Work environment

- Occupational stability

- Benefits

- Boss/leadership

Quality of life was the top issue for all IT staff, regardless of their generational category: more than nine in ten respondents said this was very or extremely important. Work environment, occupational stability, and boss/leadership were also on the "top 5 list" for all generations.8 Benefits were not on the top 5 list for Gen Xers or Boomers; this item was beat out by "my colleagues" for those two groups. ECAR didn't provide operational definitions for these items, so quality of life, work environment, and benefits for one person might mean something different for the next. More important than trying to unpack what these things mean for Millennials is seeing the relative comparison of these items to factors that institutional leaders tend to think matter to employees, such as monetary compensation (ranked 9th by Millennials), geographic location (ranked 15th), and reputation of the institution for academic excellence (ranked 18th).9

ECAR found some generational differences when IT staff were asked to rate their agreement with statements about what is most important for keeping them in their current IT position.10 The following is the top 5 list for Millennial IT staff:

- I have had opportunities to learn and grow in the past year.

- Someone at work cares about me as a person.

- At work, my opinions count.

- I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work well.

- My personal career goals are attainable.

The first three items also appear on the Gen X and Boomer IT staff top 5 lists, though in a different order. Staff in both the Millennial and the Gen X generations value having "attainable" personal career goals, and Millennials uniquely value having the materials and equipment to do their jobs well. Boomer and Gen X staff place "I have coworkers who are committed to doing quality work" and "I am highly motivated to perform my duties" on their top 5 lists.

What about skills? Millennials say the following are important for success in their current IT position:

- Ability to communicate effectively

- Ability to manage complex projects

- Strategic thinking and planning

- Ability to manage process

- Ability to use data to make decisions, plan, manage, etc.11

"Ability to communicate effectively" and "Strategic thinking and planning" made the top 5 lists for each generational cohort. Millennials' top 5 list uniquely includes project and process management, whereas Boomers and Gen Xers list "Managing relationships" and "Ability to influence others." Millennials' interest in process is probably more a function of their current situational roles and responsibilities in the workforce (managing projects vs. managing people) than a fundamental difference in core values. As young professionals gain more "people management" and leadership responsibilities, the relative position of relationship management and influence will likely match that of their more experienced counterparts.

Regardless of the reason for generational differences (whether due to situational circumstances or core values), it is important to recognize that diversity of perspectives and experiences can enhance the work environment. Generational differences don't need to be in competition. Rather, they should complement one another. Circling back to my personal experience, the last top 5 list shows me that I have something to learn from my Millennial staff who value working smarter and not harder (i.e., managing process and using data to make decisions) and they have something to learn from me, their Gen X manager, about building social capital (i.e., managing relationships and influencing others).

Millennials are more critical of themselves than other generations: they describe themselves as self-absorbed, wasteful, greedy, and cynical at higher rates than Boomers or Gen Xers. Perhaps they are just more self-aware of and honest about their shortcomings than other generations. Millennials rate themselves highly when it comes to being idealistic, entrepreneurial, environmentally conscious, and tolerant. Add being self-aware and honest to that list, and we have a solid base of characteristics for future IT managers and CIOs in the higher education IT workforce.12

For a generation that is often criticized for being overscheduled, sheltered by their parents, and not allowed to fail, Millennials reveal workplace values that are similar to those of their Boomer and Gen X colleagues. As for the differences between the generations? They provide opportunities for us all to learn and grow. By welcoming various generations into our IT organizations, we can both mentor and learn from one another.

Notes

- Richard Fry, "Millennials Surpass Gen Xers as the Largest Generation in U.S. Labor Force," Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, May 11, 2015.

- Members of the post-Millennial generation are not yet in the workforce, and the Silent (born between 1928 and 1945) and the Greatest (born before 1928) generations are typically retired from the workforce. Pew notes that the youngest Millennials have not yet been defined by a definitive chronological endpoint.

- The Pew Research Center generation categories are used throughout this article as a convenient way to speak about the multigenerational workforce. ECAR acknowledges, however, that young professionals are particularly sensitive to their generational label, as indicated in Pew Research Center, "Most Millennials Resist the 'Millennial' Label," September 3, 2015.

- Fry, "Millennials Surpass Gen Xers."

- D. Christopher Brooks, Eden Dahlstrom, and Jeffrey Pomerantz, "The IT Workforce in Higher Education, 2016," EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, March 28, 2016.

- CompTIA, Managing the Multigenerational Workforce [https://www.comptia.org/resources/managing-the-multigenerational-workforce] (October 2015).

- Gabrielle Jackson, "Forget the Career Ladder, Millennials Are Taking the Elevator," HuffPost Business, May 12, 2015.

- These lists are based on the sum of "Very important" and "Extremely important" survey response options. There were no differences in list items or order when ECAR calculated mean values of the 5-point Likert scale of these items by generation.

- The value proposition of working in higher education, including benefits such as paid time off and occupational stability, attracted many Boomers and Gen Xers to the industry but has eroded steadily in the 21st century.

- All of these items were negatively correlated with survey respondents seeking a new job. That is, respondents who agreed with these statements are not seeking new jobs in 2016. This ordered list is based on the sum of "Agree" and "Strongly agree" survey response options.

- This ordered list is based on the sum of "Very important" and "Extremely important" survey response options. There were few differences in list items or order when ECAR calculated mean values of the 5-point Likert scale of these items by generation.

- Pew Research Center, "Most Millennials Resist the 'Millennial' Label," September 3, 2015. [Should be short version.]

Eden Dahlstrom is chief research officer for the Data, Research, and Analytics (DRA) unit at EDUCAUSE.

© 2016 Eden Dahlstrom. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 51, no. 3 (May/June 2016)