Key Takeaways

- Telepresence courses help colleges and universities serve geographically distributed students and thus achieve their goals of helping all students succeed.

- An annual survey at Minnesota State University, Mankato of telepresence students has shed light on their experiences with telepresence learning compared with learning in traditional classrooms.

- Findings from these surveys suggest that focusing on building community and connecting with students on both sides of the classroom can help mitigate the technological limitations of telepresence courses today.

In 1980, Marvin Minsky popularized the term telepresence to characterize the ability to interact with the world at a geographic distance.1 Even earlier, Isaac Asimov had recognized the potential for technology to mediate face-to-face communication among geographically (or galactically) distributed individuals.2 Asimov predicted that such interactions likely would be audio/visual in nature and relevant for education.3 Indeed, colleges and universities gradually evolved toward this — first by introducing mail-based correspondence courses, then by adopting interactive television (ITV), and, more recently, by developing increasingly mature telepresence platforms.4 Some state-wide university systems are now adopting these platforms so that students previously isolated by geographic location can pursue studies that are "face-to-face, freaky real and awesome."5

As Faber Giraldo and his colleagues observed, the ability to study at a distance is becoming increasingly important as student demographics change around the world.6 In response to this trend, a growing number of departments at Minnesota State University, Mankato (USUM), have begun to adopt telepresence to deliver courses. Course options run the technical gamut, from the most basic screen-to-screen model (Cisco EX90), which represents little more than glorified ITV, to a more fully immersive environment (Cisco TX9200) that allows students to feel situated in a distributed classroom.

We have been conducting surveys of our telepresence students at MSU since the spring of 2014. Initially (with our colleague Candace Raskin), we focused on students in our Educational Leadership Department; we subsequently extended our study to students in telepresence courses across campus. Our goal throughout has been to better understand how students experience telepresence courses and how we might improve the way in which we teach them. Here, we describe our findings thus far and offer a few recommendations for improving the student experience in telepresence courses.

Survey Results

To date, we have collected data from 55 students across five departments representing a cross-section of bachelor's (n = 14), master's (n = 22), educational specialist (n = 2), and doctoral (n = 17) programs of study. In our brief survey, we asked students to compare their current experiences in telepresence courses with what they would expect in equivalent face-to-face courses (see the sidebar, "Survey Questions").

Survey Questions

Please indicate your response to each question below:

Zero (0) is Strongly Disagree and five (5) is Strongly Agree:

- I learned about the topics of study in my telepresence courses.

- I learned as much about the topics of study in my telepresence courses as I would have in more traditional courses.

- I was satisfied with the quality of communication in my telepresence courses.

- I think the quality of communication in my telepresence courses was equivalent to what I would have experienced in more traditional courses.

- I enjoyed the sense of community in my telepresence courses.

- I think the sense of community in my telepresence courses was equivalent to what I would have experienced in more traditional courses.

- I was comfortable with the technology in my telepresence courses.

- I was as comfortable with the technology in my telepresence courses as I would have been with the technology in more traditional courses.

- Overall, I was satisfied with my telepresence courses.

- Overall, I was as satisfied with my telepresence courses as I would have been with more traditional courses.

- What would improve the telepresence experience for students in the future?

We developed this survey based on our own experiences teaching telepresence courses. It focuses on five key factors:

- learning,

- quality of communication,

- sense of community,

- comfort with technology, and

- overall satisfaction.

The results of the survey revealed important disparities in how students perceived each course type.

Students reported telepresence courses to be equivalent to traditional face-to-face courses on two factors: quality of communication (t[54] = 1.563, p = .124, d = .21) and comfort with technology (t[54] = 1.993, p = .051, d = .27). These results were congruent with our early expectations.

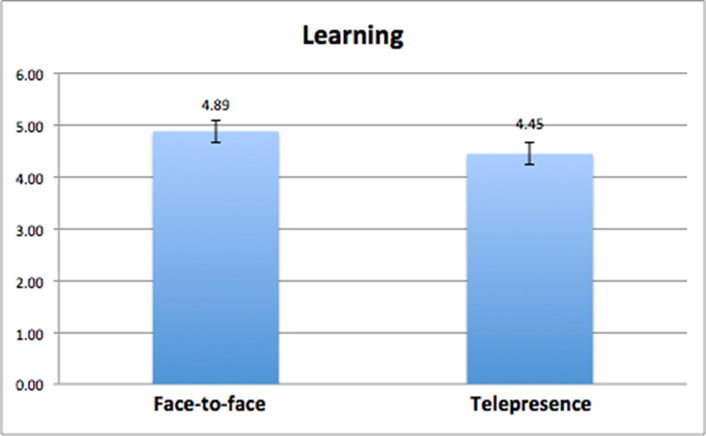

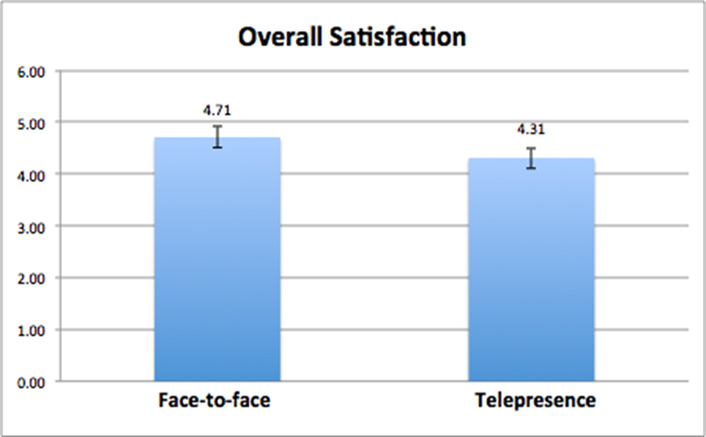

In contrast, we did not expect students to indicate that, in telepresence courses, they learned less (t[54] = 3.690, p = .0005, d = .50) and experienced less overall satisfaction (t[54] = 4.734, p = .00016, d = .64). Although for both of these factors, the differences in ratings between telepresence and traditional face-to-face courses was quite small, the fact remains that students reported a discernible difference in experience. See figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Student perceptions of learning

Figure 2. Student perceptions of overall satisfaction

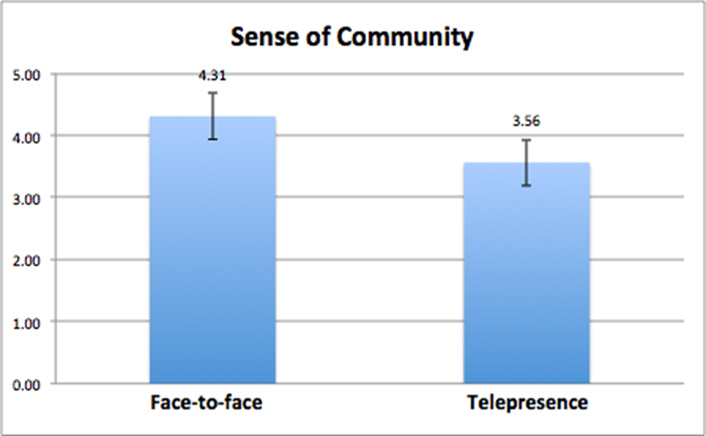

Finally, and most notably, telepresence students indicated a large negative difference in their sense of community (t[54] = 5.408, p = .0000015, d = .73). We were not surprised at this outcome; indeed, our concern about sense of community was our motivation for investigating student perceptions in the first place. See figure 3.

Figure 3. Student perceptions of sense of community

We suspect that the diminished sense of community in telepresence courses might be a key factor in other reported differences in learning and overall satisfaction. Our experiences teaching via telepresence routinely suggest that students struggle to connect with their geographically mirrored classmates. Instead of developing a cohesive sense of community among the class as a whole, we regularly observe that students on either side of the class related primarily with their local peers. A recent study by our colleagues also found a lower sense of community in telepresence courses.7

Moving Forward: Recommendations

Telepresence offers colleges and universities an opportunity to meaningfully serve the increasing number of geographically distributed student populations and thus achieve their goals of preparing students for successful lives.8 Although the current state of the art is far from what Minsky envisioned in his manifesto, we are optimistic about the future. To assist in its arrival and the realization of Minksy's vision, we offer the following three recommendations.

Focus on Community

First, faculty members must actively aim to create community in telepresence courses. This need was acknowledged repeatedly in our surveys. As one student observed, "since half of the class is 90 miles away … it is difficult to really get acquainted with that group."

Indeed, our research indicates that the very technology that allows for meaningful interaction across distances simultaneously limits the logistics of those interactions. Thus, faculty members must intentionally compensate for this challenge and take extra steps to connect students on both sides of the classroom, in-person, and telepresence.

In our department, for example, some faculty members alternate their physical presence on a weekly basis, traveling between classroom sites to build a community of scholars among all students. Faculty members should also intentionally direct their comments equally to both sides of the distributed classroom, so no one feels like they are "sitting behind the professor." Anecdotal reports from our students suggest that such efforts result in greater connection among all class members.

Provide Training for Faculty

Second, faculty members who teach via telepresence must receive training in the platform. For example, one student complained that some faculty "spent a fair amount of class time trying to get the technology piece to work." Another student indicated that faculty being trained in teaching methods for telepresence classrooms might better support "communication between students on both sides."

Many colleges and universities already offer training in online pedagogies; such options could be easily expanded to incorporate telepresence and remain well within budgetary reason. Such training might focus on several factors, including:

- assisting faculty to better understand the logistics of actively teaching while sitting,

- emphasizing the importance of turning to address both halves of the distributed classroom, and

- becoming familiarized with the technology prior to the start of term.

Promote Faculty-Student Connections

Finally, faculty must remain mindful that education functions largely through relationship. As one student opined, "the instructor is a big part of the telepresence experience. He/She needs to be able to involve [both sides of the class]." In our experience, it is all too easy for faculty to inadvertently ignore the geographically distributed half of the class.

Our own and others' work9 suggests that students enjoy telepresence courses. The question, then, is how we might leverage the "wow factor" of the technology to promote more meaningful community.

Conclusion

The sense of community within telepresence courses might improve as the technology continues to mature and students feel more comfortably situated in distributed classrooms. In the interim, attention to the human side of teaching can help balance the technological limitations of telepresence coursework today and move us a few steps closer to Minksy's vision.

Notes

- Marvin Minsky, "Telepresence: A Manifesto," Omni, June 1980.

- Isaac Asimov, The Naked Sun (New York: Doubleday, 1957).

- Isaac Asimov, "Visit to the World's Fair of 2014," New York Times, August 16, 1964.

- 7 Things You Should Know about Telepresence, EDUCAUSE, 2009.

- Peter Rettler, "Telepresence: Seamlessly Connecting Classes across Campuses," EDUCAUSE Review, October 7, 2013.

- Faber Giraldo, Angela Jiménez, Helmuth Trefftz, Juliana Restrepo, and Pedro Esteban, "Distance Interaction in Education Processes Using a Telepresence Tool," in Technological Developments in Education and Automation (New York: Springer, 2010), 509–512.

- Carrie L. Lewis, Qijie Cai, Michael Manderfield, and Jude A. Higdon, "Student and Faculty Perceptions of Telepresence Courses," EDUCAUSE Review, July 20, 2015.

- Diana G. Oblinger, "From the Campus to the Future," EDUCAUSE Review, January/February 2010.

- Mary F. Grasinger, "Successful Distance Learning: Teaching via Synchronous Video," College Teaching, vol. 47, no. 2, 1999, pp. 70–73.

Jason Kaufman, PhD, EdD, is an associate professor of educational leadership at Minnesota State University, Mankato and a licensed psychologist. His teaching focuses on the use of scientific thinking to promote change through educational leadership. His research seeks to answer the question: How can we utilize mind-body practices to promote the development of executive functions? He maintains a corollary interest in the intersection of technology and sense of community in the higher education classroom. He also enjoys nature photography as time and travel allow.

G. David McNay is a master's student of Experiential Education in the Department of Educational Leadership at Minnesota State University, Mankato and a research assistant in the same department. He has a background in environmental outdoor education and great interest in promoting outdoor leadership and best uses for technology.

© 2016 Jason A. Kaufman and G. David McNay. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.