National Cyber Security Awareness Month (October) provides those engaged in cybersecurity a chance to discuss the importance of security safeguards. This article takes a look at the state of cybersecurity in higher education.

National Cyber Security Awareness Month (NCSAM) always brings fresh attention and perspective to risks inherent in our connected lives — and, more importantly, to safeguards to help reduce those risks. While 2015 hasn't seen the same number of high-profile data breaches, nor the number of vulnerabilities on highly utilized technologies as previous years, October still provides those engaged in the field of cybersecurity a chance to talk to and hear from others about the importance of security safeguards, a chance to reengage and double-down in their efforts.

It is with NCSAM in mind that we consider the state of cybersecurity in the higher education landscape.

Things Are Not Always What They Seem

What would the popular media have us believe about the state of cybersecurity in higher education?

- Every higher education breach reported is a "wake-up call."1

- Education is "a near pervasive leader" in infections.2

- Our "highly regulated industry" has a price tag of almost $300 per record per data breach.3

- We implement fewer controls in our IT environments.4

- Institutions are unwitting hosts of malicious activity.5

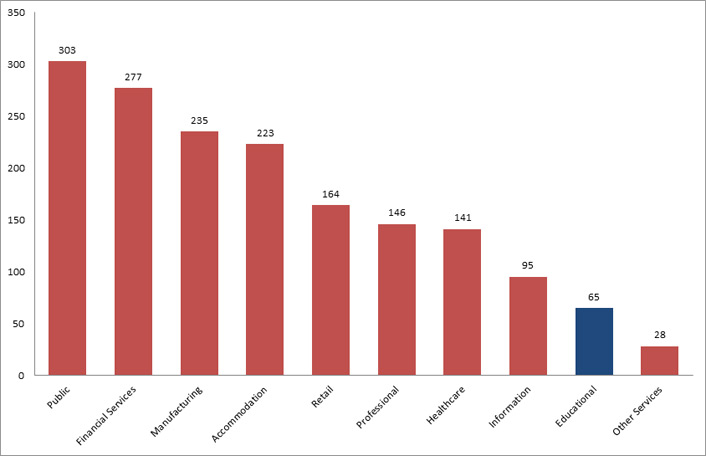

We believe the education industry's poor security reputation is undeserved and merits a closer look. The Verizon 2015 Data Breaches Investigation Report shows the education sector (which includes higher education as well as K–12) is the 11th highest sector in reported total security incidents and the 9th highest sector for reported security incidents with confirmed data loss.6 The 65 confirmed incidents of data loss reported in the education sector is far less than half of the top three industries: public (303), financial services (277), and manufacturing (235); see figure 1.

Figure 1. Top 10 industries with confirmed data loss, Verizon report.

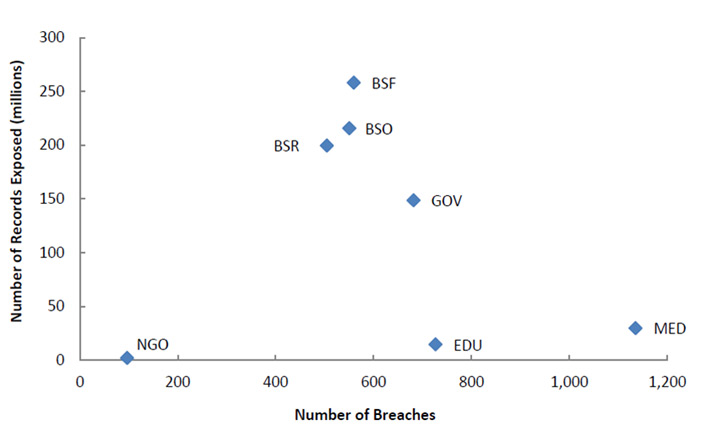

Recent EDUCAUSE research reflects the same trend, showing that while the number of data breaches in higher education seems high, the number of records exposed in those breaches is actually low.7 This difference is especially notable when compared to other industry sectors like the government, financial and insurance services, and retail and merchant services. While these sectors have lower numbers of breaches, they disclose greater numbers of records containing personally identifiable information in those breaches. See figure 2, in which the industry sectors are BSF = Businesses (financial and insurance services); BSR = Businesses (retail/merchant); BSO = Businesses (other); EDU = Educational Institutions (all); GOV = Government and Military; MED = Healthcare; and NGO = Nonprofit Organizations.

Figure 2. Number of records exposed vs. number of breaches reported8

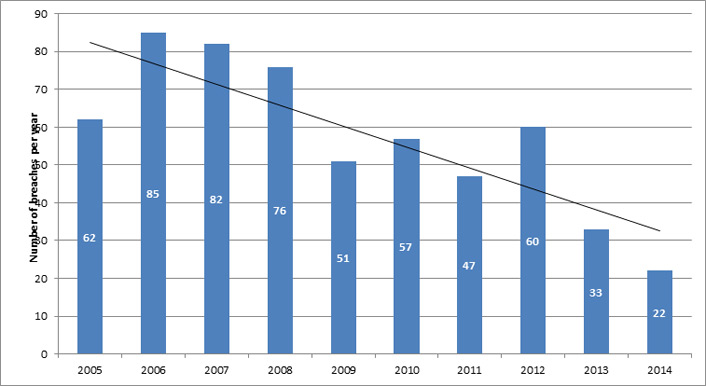

Additional analysis of the data used in earlier EDUCAUSE research shows a significant downward trend in the number of yearly data breaches reported in the higher education industry during the period 2005–2014 (see figure 3, drawn from Privacy Rights Clearinghouse data with EDUCAUSE analysis). This downward movement comes at a time when only 2 percent of the IT budget at U.S. institutions is spent on information security, yet 71 percent of U.S. institutions have mandatory information security training for faculty or staff.9 It may be that our efforts of the past 10 years, focusing on providing cybersecurity awareness training to various higher education audiences (students, faculty, and staff) continues to result in a more security-aware campus environment.

Figure 3. Number of data breaches per year with linear trend line for higher education as an industry10

The data further suggest that the education sector really isn't that different from most industry sectors in terms of the number of reported data breaches per year. For instance, we know from work at the REN-ISAC that all sectors experience the same types of malware, face the subsequent risks of malware infection, and must take the same actions to mitigate the risks. Higher education's open environments, large population of unmanaged student devices, and less intrusive endpoint controls likely contribute to the high number of potential malware events experienced in the education sector. Without appropriate discussions concerning context, it may look like malware infiltration for education is worse than other sectors. Yet, when we look at the number of breaches per year, per industry in the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, it appears that education as an industry is no greater a victim of malicious activity "in the wild" than other industry sectors.11

Many of the security issues that higher education IT has struggled with for years (patchwork industry regulation, decentralized IT operations, issues of network segmentation for public and sensitive resources, and the consumerization of IT) now seem to be issues faced by industry as well.12 The strategies and safeguards employed by higher education to combat these issues provide successful models that could be employed elsewhere — and we have the data to show their success. For example, we know from the EDUCAUSE Core Data Service13 that:

- 71 percent of U.S. institutions have mandatory information security training for faculty or staff.

- 78 percent of U.S. institutions have conducted some sort of IT security risk assessment.

- The most commonly deployed information security systems and technologies are malware protection (92 percent), secure remote access (90 percent), and secure wireless access (85 percent).

- 50 percent of U.S. institutions track information security metrics.

Look Behind the Curtain

Frankly, if it's your institution suffering from a breach involving data loss or facing malicious activity, these statistics might not mean much. Another important analysis considers the safeguards deployed across universities and colleges and how they reduce risks. Information security professionals must constantly survey the threat landscape and deploy tools and techniques that protect institutional resources without greatly inconveniencing system users. In doing so, they often rely on their peers for information on what works.

Significant strides have been made in the implementation of technological and administrative safeguards in colleges and universities in recent years. To protect against phishing campaigns like the recent University Payroll Theft scheme,14 many institutions are deploying two-factor authentication. In a recent informal poll of REN-ISAC members on a mailing list, 71 percent of respondents indicated adoption of this type of authentication. Other safeguards showed nearly the same rate of adoption:

- Federated identity management, which reduces the threat by limiting the number of logins

- Log aggregation techniques and technologies that allow for easier and quicker pinpointing of anomalous system events (which could connote an infiltration or breach)

- Whole-disk encryption, which fully encrypts laptops and workstations, sheltering sensitive data from physical capture

Additional protections with over 50 percent of adoption by REN-ISAC poll respondents include sensitive data locators, workstation software vulnerability scanners, web application vulnerability scanners, IT risk assessment frameworks, and the EDUCAUSE information security guide.15

In broad strokes, this activity may signal an increasing understanding of risks (including compliance risks) and a greater willingness to deploy tools that successfully protect institutional resources. It might also indicate an increase in sophistication in the tools and technologies — two-factor authentication is easier to deploy and use now than ever before.

It's Not Magic: Safeguards That (Almost) Always Work

No safeguard always works — security represents a juggling performance between security professionals and bad actors, with each trying to gain and keep an advantage over the other. While there are always situation-specific needs dictated by policy, culture, and risks, a number of safeguards have been proven to improve cybersecurity and reduce risks (table 1).

Table 1. Technical and administrative safeguards

|

Technical |

Administrative |

|---|---|

|

Adopt a defense-in-depth approach — don't rely on a single control. |

Dismiss the "I'm not a target" mentality. |

|

Use scanning and inspection tools to find vulnerabilities and identify out-of-date software. |

Assess your environment (including building control systems and cloud-based systems) periodically and deploy safeguards to manage risks according to organizational need. |

|

Protect networks where sensitive functions are performed or sensitive data is stored using network security tools like firewalls and access control lists (ACLs). |

Document policies and procedures protecting institutional information, IT resources, and credentials, including incident management and business continuity. |

|

Use robust, reliable, state-of-the art access and identity management techniques. |

Train security professionals, software developers, system administrators, and other IT professionals in threats, risks, and cybersecurity techniques. |

|

Aggressively patch operating systems and applications. |

Commit to ongoing education for end users to reinforce good cybersecurity habits. |

|

Quickly block or quarantine compromised hosts. |

Document, test, and maintain up-to-date backup procedures to mitigate risks posed by ransomware and other threats. |

|

Employ proactive protections, such as IDS, IPS, and DNS sinkholes.* |

Collect logs and monitor for incidents and suspicious behavior. |

* Note: IDS = intrusion detection system, IPS = intrusion prevention system, DNS = domain name system, and DNS sinkhole = a server that gives out non-routable IP addresses to prevent access to legitimate domains

For more tips and techniques, refer to the Information Security Guide: Effective Practices and Solutions for Higher Education

This Magic Moment

National Cyber Security Awareness Month each October is a good time to assess where we've been and reflect on our progress in information security in higher education. There's always more to do — for the security professional and for every technology user. What has worked well, and how can we leverage those successes to minimize additional risks? What can we do differently or better? How can we use the strengths of our community to keep improving?

It is our community strength that moves us forward. We in higher education are fortunate, as we have the opportunity to meet as a professional community early in the year at the EDUCAUSE Security Professionals Conference and the Research and Education Networking Information Sharing and Analysis Center (REN-ISAC) Member Meeting. An intangible atmosphere develops when security professionals get together each year at these meetings: a sense of belonging; a sharing of kudos for a job well done when a particular problem is tackled successfully; and excitement when a new security technique succeeds at keeping critical resources protected. Both formal and informal mentoring opportunities occur, and the animated "hallway track" is often more personal and often every bit as powerful as the planned sessions.

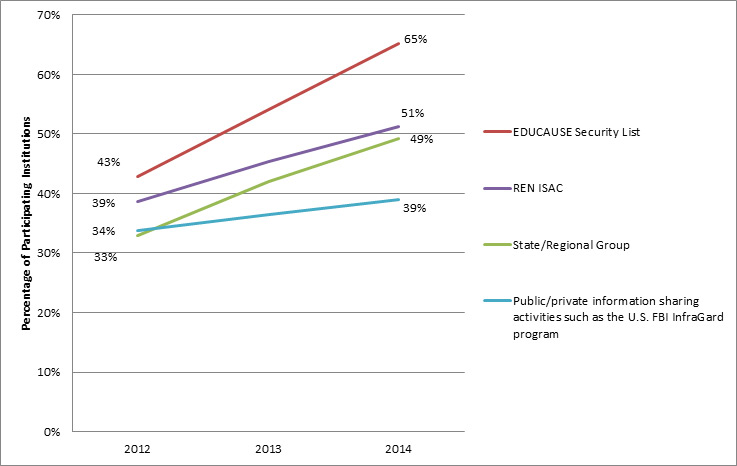

We know that that addressing higher education information security issues requires a collaborative approach. Over the past three years, participation in multi-institutional collaborations dedicated to improving information security has increased (see figure 4). Organizations like EDUCAUSE, Internet2, and the REN-ISAC are proof that the information security community reflects an "all for one, and one for all" mentality.

Figure 4. Participation in multi-institutional collaborations16

This esprit de corps extends beyond institutional and organizational boundaries. Leadership for both the REN-ISAC and the EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Initiative includes named representatives from each organization and from Internet2. Internet2 working groups include participants from EDUCAUSE and the REN-ISAC. Collaboration within the community is active and strong. When the REN-ISAC issues information security advisories and alerts, those warnings are shared throughout EDUCAUSE and Internet2. The effectiveness of this model is evidenced by downstream sharing in the community: The REN-ISAC "Advisory: University Payroll Theft Scheme"17 generated related publications at 14 colleges and universities.

What's notable about higher education is the willingness to share, collaborate, and help colleagues. This culture of collegiality is very evident in our information security community. I'm very impressed at the cross-organizational collaborations between EDUCAUSE, REN-ISAC, and Internet2 members.

In addition to multi-institutional collaborations, higher education values individual contributions to securing the higher education ecosystem. For instance, the Information Security Guide: Effective Practices and Solutions for Higher Education never would have come about without the dedication and countless volunteer hours of many talented higher education information security professionals. This resource, under a constant state of revision and most recently fully updated in 2014, provides practical approaches to preventing, detecting, and responding to information security problems in a wide range of higher education environments.

It is against this backdrop — the enthusiasm, commitment, and collaboration of higher education cybersecurity professionals — that higher education continues to remain grounded in combatting risks, responding to exposures and breaches, and preparing for future challenges.

Join the Higher Ed Information Security Community

There is no shortage of talent in the higher education information security community, just as there is no shortage of ways to get involved in the community. Here are just a few of the participation options available:

- Join the EDUCAUSE Security Discussion list

- Volunteer your time and talents for an EDUCAUSE or Internet2 security working group

- Join the REN-ISAC and attend its annual membership meeting

- Attend the Security Professionals Conference each spring

- Attend monthly InCommon IAM Online webinars

- Attend webinars by cybersecurity vendors and partners.

- Attend the Internet2 Global Summit, Technology Exchange, or workshops

- Follow @HEISCouncil on Twitter for higher education information security news and resources

Notes

- Carl Straumsheim, "A Playground for Hackers," Inside Higher Ed, July 6, 2015; Jeff Alderson, "How Safe Is Your Student Data? Data Privacy Implications for Higher Education" [http://www.eduventures.com/2015/03/how-safe-is-your-student-data-data-privacy-implications-for-higher-education], Wake-Up Call, Eduventures, March 3, 2015.

- Verizon, 2015 Data Breaches Investigations Report, April 2015.

- Ponemon Institute Research Report, Cost of Data Breach Study: Global Analysis, May 2015.

- Verizon, 2015 Data Breaches Investigations Report.

- Department of Homeland Security, Intelligence Assessment: (U//FOUO)) Malicious Cyber Actors Target US Universities and Colleges , January 16, 2015.

- This list excludes breach reports where the originating industry is "unknown." Verizon, 2015 Data Breaches Investigations Report, 2, 4.

- Joanna Lyn Grama, "Just in Time Research: Data Breaches in Higher Education," EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR), May 2014.

- EDUCAUSE analysis of 2005–2014 data from the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, in the publication by Joanna Lyn Grama, "EDUCAUSE Just in Time Research: Data Breaches in Higher Education," May 20, 2014.

- Joanna L. Grama and Leah Lang, "CDS Spotlight: Information Security," Research Bulletin, ECAR, July 3, 2015.

- Grama, "Data Breaches in Higher Education."

- Ibid.

- Michael Corn, "Preventing Cyber-Attacks in Universities with Operational Collaboration," CIO Review, July 2015.

- CDS Benchmarking Report, EDUCAUSE Core Data Service Almanac, All US Institutions, February 2015; and Grama and Lang, "CDS Spotlight: Information Security."

- REN-ISAC, "Advisory: University Payroll Theft Scheme," November 12, 2014.

- HEISC, EDUCAUSE, Information Security Guide: Effective Practices and Solutions for Higher Education, May 1, 2014.

- EDUCAUSE, CDS Benchmarking Report, 2014.

- REN-ISAC, "Advisory: University Payroll Theft Scheme."

Kim Milford, JD, serves as the executive director for the Research and Education Networking Information Sharing and Analysis Center, REN-ISAC. In this role, she participates in the National Council of ISACs on behalf of the research and education networking community. Prior to this role, Milford was chief privacy officer at Indiana University, information security officer at the University of Rochester and information security manager at the University of Wisconsin, leading initiatives such as disaster recovery planning, identity management, incident response, and user awareness. Milford graduated from Saint Louis University with a BS in Accounting and earned her JD at John Marshall Law School.

Joanna Lyn Grama, JD, CISSP, CIPP/IT, CRISC, directs the EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Initiative and the IT GRC (governance, risk, and compliance) program. She has expertise in IT security policy, compliance, and governance activities, as well as data privacy. She is a frequent speaker on a variety of IT security topics and is also the author of the textbook Legal Issues in Information Security (2nd ed., 2014). Grama graduated from the University of Illinois College of Law with honors.

© 2015 Kim Milford and Joanna Lyn Grama. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.