Key Takeaways

- Improving student success requires seeing the whole system of undergraduate education in institutional data, and then working to integrate component parts to inform improvement.

- University of South Carolina Student Affairs enlisted IT staff in a collaborative project to develop a system to create and manage standardized records of student involvement in noncredit, educationally purposeful programs and services beyond the classroom.

- The increasing interdependence of systems across campus requires IT involvement with many different stakeholders and projects to ensure complete and accurate records that increase the ability of different organizations to improve student success.

Have you ever made a New Year's Resolution to lose weight? According to the website Statistic Brain, it was the most popular resolution in 2015. After we resolve to lose weight, what's the next thing we do? We begin to count the calories we eat with calorie-counting apps like Lose it! and My FitnessPal and track the calories we burn [http://www.insweb.com/news-features/fitness-tracking-devices.html] through exercise with wearable devices [http://www.insweb.com/news-features/fitness-tracking-devices.html] like Fitbit and FuelBand. In the past, we had to measure and record this information manually but, as in so many aspects of our lives, technology has changed the way we collect and use information for improvement.

In this example, we gather this information so that we can (1) consider how our current diet and exercise habits produce our current weight, and (2) determine what adjustments we should make to achieve the results we want — our target weight. Although the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching might not use this example to illustrate their Improvement Research, it nicely demonstrates the utility of principle #3 of their Core Principles of Improvement: to improve, we must first be able to "see the system that produces the current results."1

This useful principle also provides a framework for conducting assessment for improvement — in my case, helping student affairs departments, and the university, achieve better results. As associate vice president for planning, assessment, and innovation, my primary purpose is to contribute to improving student success in undergraduate education at the University of South Carolina (USC). My unique role in improving student success is through assessment and improvement of student support services and enrichment programs in the Division of Student Affairs and Academic Support.

At USC, key indicators of undergraduate student success are persistence (retention), timely graduation, and postgraduation employment or graduate school admission. To apply Carnegie improvement principle #3 to the goal of improving undergraduate student success at USC, first we must understand the system that produces current student success results. The core of the system of undergraduate education is, of course, the academic program; another important component of the system is the learning environment provided by the institution. At USC, we intend to provide a learning environment that supports and enriches the experience of every student, because we know that each student's personal circumstances and unique educational experiences contribute to persistence, timely progress to degree, and employability at graduation.

To lose weight effectively requires data about both diet and exercise; if we ignore one or the other, we will be less successful in achieving the desired outcome. Similarly, to improve student success requires seeing the whole system of undergraduate education that produces the current results. In addition to the academic and demographic data already included in our student information management system, we need access to systematic data about student participation in support and enrichment programs. Student Affairs enlisted the collaboration of our IT colleagues to develop a system to create and manage standardized records of student involvement in noncredit, educationally purposeful programs and services beyond the classroom. In the weight-loss example, technology has become a key factor in providing easy access to useful data for improvement. Information technology plays an increasingly integral role in our use of data for improving student success.

The Problem to Solve with IT Collaboration

Providing useful, personalized information to help one individual lose weight is a very different problem from managing useful, personalized information to help more than 25,000 undergraduates succeed. The data of interest are generated by student involvement in support and enrichment programs provided by more than 40 organizational units that historically have not shared common data management practices. These units constitute the USC Division of Student Affairs and Academic Support, which includes enrollment management functions (admissions, the registrar, financial aid), the career center, housing, health services, student life (student organizations, the leadership and service center, campus recreation), and more. Instead of tracking steps taken or calories consumed, we track student involvement in hundreds of programs with multiple purposes.

Our departments require these student involvement data for their strategic planning and assessment processes, which include documenting a continuous cycle of improvement. These documents also serve to demonstrate accountability and transparency by providing information to stakeholders about the educational role provided by each department in support of the institution's mission for undergraduate education.

In this continuous improvement process, departments are expected to provide and analyze data about who they serve (student demographics and characteristics), how they engage students in specific programs and services, the results they intend to achieve, and the results they actually achieve with their efforts. At the division level, we assimilate this information from departments across the division and provide analysis of these programs' contributions to student success, as measured by student retention, graduation, and postgraduation employment. Annually, we are asked to provide data-based analysis of the division's key strengths and accomplishments, areas for improvement and plans for addressing these areas, and key issues predicted for the upcoming year. This analysis helps us make the case for needed resources and supports the division's annual budget review and any requests for new funding.

Evolution of the Problem: Why We Need IT Collaboration

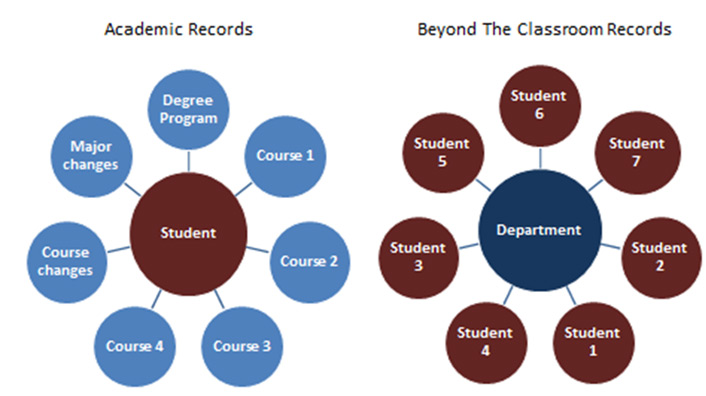

In the past, data about student participation in beyond-the-classroom activities have not been standardized in format or content and were collected in independent systems within departments rather than in a central records management system (see figure 1). These fragmented processes evolved over time because students are not required to participate in beyond-the-classroom activities, and such participation does not earn credit toward graduation requirements, so there was no perceived need to include these records in information systems designed to monitor students' academic status and progress to degree.

Figure 1. Separate data systems exist for academics and beyond the classroom

However, the number and educational depth of student support services and enrichment programs have increased over time, as has the cost of providing them. Record-keeping practices must also evolve to accommodate these changes and provide actionable data about student involvement in these activities in order to inform student success efforts. Again, we are guided by the Carnegie Core Principles of Improvement: principle #4 states, “We cannot improve at scale what we cannot measure.” As we move toward greater transparency and accountability, we must be able to systematically determine and demonstrate the educational impact and return on investment of all programs and services. This analysis must include noncredit programs provided beyond the classroom. Advancing technology capabilities make it possible to improve these processes and raise expectations for better analysis of their value added.

Demand for resources to support new projects is high and availability is limited. Improving assessment of the learning environment at USC is a priority because it is integral to our mission for undergraduate education. To support our academic programs, USC purposefully provides a rich learning environment beyond the classroom, offering a diversity of enrichment and support opportunities including leadership development, civic engagement, global learning, and numerous programs and services for personal development and well-being. To build on this institutional strength, USC recently implemented a quality enhancement plan focused on helping students integrate their learning within and beyond the classroom to further advance their educational experience.

Source: Alexander A. Astin, "Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education."

Figure 2. Learning is proportional to purposeful involvement

In keeping with research indicating that student engagement matters for student learning and success2 and identifying characteristics of practices with high educational impact,3 USC invests significant resources to provide support and enrichment opportunities to help students succeed and thrive. However, due primarily to some of the data challenges described here, we have been limited in our ability to provide evidence of the educational impact of programs provided for students on our campus. The university gains useful information to achieve its goals by more systematically assessing the educational impact of student involvement in specific programs and in patterns of programs. In the process, USC realizes the added benefit of increased transparency regarding these noncredit programs and services as well as their return on investment. We use learning management systems to track student activity in courses and to evaluate course materials because we know that student engagement with effective course materials is related to their success in the course. Similarly, we believe student engagement at the macro level — with educationally purposeful programs and services outside the classroom — is related to their success in college (see figure 2). Providing user-friendly staff access to actionable data on the holistic undergraduate experience of each student paves the way to a better experience for each student and to data-driven improvement of programs. This systematic approach to managing information for beyond-the-classroom programs prompted the collaboration with IT.

Collaboration: Progress, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

Following the IT division's project management practices, an IT project manager leads our project team, which includes IT technical experts and a business analyst. Because the student records created and managed in this new system are part of each student's official educational record, sponsorship of the project is shared by Bob Askins, senior associate registrar, and me. Executive sponsors include senior leadership in Academic Affairs (the Provost's Office), the Division of Information Technology, and the Division of Student Affairs and Academic Support.

The project is defined as the development and integration (with academic data systems) of Beyond the Classroom Matters, a system for collecting and managing actionable data on student involvement in noncredit, educationally purposeful support and enrichment programs. The project consists of three phases, with the first phase, development of an online catalog (database) of beyond-the-classroom programs, now operational. We expect to complete phases two and three within this academic year. These phases focus on implementing a process and tools for collecting standard student involvement records in a central repository (with appropriate verifications for accuracy and integrity), and creating a data interface with the academic records information system.

I have found the collaboration both positive and productive, and an educational experience for me. It has reminded me of the value of a deliberate process of thinking through each step, a process necessary to document requirements for every action and every element of the system. Although it still seems magical when a new application works as grandly envisioned, I have a deepened appreciation for the IT expert who works through detail after detail to make the magic happen!

To say we have had language barriers in the project is too strong a statement, so I'll say we have noticed some language "speed bumps" in this collaboration because IT and Student Affairs have their own sets of jargon and acronyms. So, I learned a new language, of sorts, with terms like project management, enterprise applications, and operational data store. My IT colleagues learned about student affairs terms like holistic student development, integrative learning, and assessment rubrics. I increasingly realized how integral information technology has become to every function of the university and think perhaps my IT colleagues have gained a new appreciation for the complexity of the undergraduate student experience.

Another challenge was the shared ownership of this project. Primary ownership of most collaborative projects is clear; however, the complexity and breadth of this project highlights the increasingly interdependent nature of our organizational functions and systems, as it crosses several internal organizational boundaries. This project involves an information system that will interface with other university information systems (IT). The purpose of the new system is to manage standardized data defined and generated primarily by student support and enrichment programs (Student Affairs and Academic Support). The records created and managed in the system are considered official student records (Registrar), with all the requirements that entails. These records of educational experiences will be available to students and will be used to improve student success in undergraduate education (Academic Affairs). Project ownership lines are blurred, and it made me realize how all of our systems are increasingly interconnected (or need to be) and interdependent.

From my student affairs perspective, this seemed more like an IT project at first. I realized somewhere along the way that nearly every project these days is an IT project to some extent. Advancing technology seems to have also advanced stakeholders' expectations (students, parents, others) for transparency and easy access to institutional information, because they receive that in many other aspects of their lives. The importance of collaboration across the university regarding data management practices, data collection and analysis tools, and expectations for use by common target populations (advisors, for example) quickly becomes apparent. The line between "technology project" and "student affairs project" has blurred — we can't do many student affairs projects without IT as a partner. I imagine this is true for most areas of the campus.

Observations and Recommendations

Going through this process of collaborating with IT on a project to support undergraduate student success by improving our institutional data surfaced a number of insights and advice for others approaching similar collaborative projects.

Advice to Student Affairs Colleagues, or Things I Wish I Had Done Sooner

- Get to know your IT colleagues; having already established professional relationships and connections will benefit future collaborations.

- Take steps to improve your own IT knowledge and skills so that you can more effectively help the IT staff help your organization.

- Communicate about the work of your department with your IT colleagues, even when not working directly with them on a new project. The more they know about your work, the better equipped they will be to help you identify innovative tools and processes to advance your work.

- Stay informed about the work of the IT division. The more you know about their work, the more you will understand how your work aligns with theirs.

Advice to Institutions: Why You Should Encourage Collaborative IT Partnerships

Students persist, graduate, and get jobs, one student at a time. Universities tend to assess undergraduate education outcomes in aggregate — retention rates, graduation rates, employment rates — but every student has a unique educational experience that affects these outcomes. If an institution wants to improve the educational experience for all students, it must know what happens for each student individually. Although all students in a degree program complete courses from the same curriculum, each student's experience outside the classroom is singular: some serve in leadership roles, some engage in community service, some participate in career-planning programs, some get involved in intramural sports or student organizations. Some experience a crisis of some kind — serious health issues, financial problems, or the realization that they chose the wrong major — and seek assistance on campus in working through these problems. Some live in campus learning communities in the residence halls, some hold part-time jobs on campus, some have parents who involve themselves in the parents' program. Some don't do any of these things. To fully understand the many variables that contribute to student success, we need to see the holistic educational experience of individual students.

When we can fully see the system that produces the current results — retention, graduation, employment — we can more effectively determine what works for which students and use that information to improve programs and access to them. As a result, we can improve student success. Returning to the New Year's resolution analogy, we know that just assessing our weight every day doesn't change it. We also have to assess the system (diet, exercise) that is producing the current outcomes, to inform change in that system for improvement.

Student success has become everybody's business, including student affairs and IT. Stakeholders now expect quick, easy access to systematic, accurate information and institutional processes. As technology and data management become increasingly integral to the delivery of educational programs and services, deeper collaboration and communication across organizational lines are required. In particular, the evolution of the role of student affairs programs, growing interest in data-based decision making, increasing demands for transparency and accountability, and advancing technology capabilities have come together to create the perfect storm of opportunity and necessity for collaboration of student affairs and IT in order to increase student success.

Interdependence Rising

You might wonder why a student affairs person would write this article for EDUCAUSE. Nearly every project seems to have an IT component these days, and every job on campus seems increasingly interdependent with IT roles and functions, especially student affairs practitioners. This article describes just one example of student affairs-IT collaborations that are, or will be, occurring on campuses everywhere. Additional collaborative projects identified on our campus include management of IT applications (such as those used for collecting and providing information to students and advisors); development of privacy policies that acknowledge new ways of accessing and using student information; and alignment of analytics tools and practices across the university. This increasing interdependence is necessary in order to most effectively improve student success in our system of undergraduate education.

Notes

- "The Six Core Principles of Improvement," Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Alexander A. Astin, "Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education," Journal of College Student Development 40, no. 5 (September/October 1999): 518–29.

- George D. Kuh, High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and why They Matter (Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2008).

Pamela J. Bowers is associate vice president for planning, assessment, and innovation in the Division of Student Affairs and Academic Support at the University of South Carolina. She serves as a co-chair of The Reinvention Center’s Student Success/Learning Analytics Network. She previously led institutional assessment of academic programs and general education at Oklahoma State University, and served as a peer consultant-evaluator for the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. She holds a PhD in Applied Behavioral Studies in Education from Oklahoma State University.

© 2015 Pamela J. Bowers. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.