Key Takeaways

- In 2012, Duke University began using MOOCs to promote innovation in teaching and learning within the campus community, with the goal of importing successful new pedagogical ideas into Duke classrooms.

- Since that time, 30 instructors from 28 departments have developed 31 MOOCs on Coursera, attracting 2.8 million enrollments and issuing more than 72,000 certificates.

- Various examples show how these instructors changed their teaching approach in both MOOCs and traditional courses, including by improving classroom materials and activities, crafting better measures of student learning, and experimenting with new pedagogies to increase engagement and learning.

Kim Manturuk, Manager of Program Evaluation, and Quentin Ruiz-Esparza, Project Coordinator, Duke University

Although much of the attention given to massive open online courses (MOOCs) focuses on their ability to reach millions of learners worldwide, one of Duke University's original primary objectives for getting involved with MOOCs was to use the courses to promote innovation in teaching and learning within the Duke campus community. At the beginning of Duke's MOOC venture in 2012, Duke President Richard Brodhead said,

"We see the online environment as a sphere for experimentation where faculty can develop and pilot new teaching methodologies. If the pedagogical innovations prove successful, faculty members can devise ways to import these ideas back into their Duke classrooms."

In the three years since the venture launched in 2012, MOOCs have led to surprising pedagogical outcomes. Duke faculty members have invested heavily in the university's exploration of MOOCs, with 30 instructors from 28 departments developing 31 MOOCs on Coursera (figure 1). Across 66 individual course sessions, Duke MOOCs have had 2.8 million enrollments and issued more than 72,000 certificates. Today, faculty members continue to design new MOOCs, launch additional course sessions, and seek out new uses for MOOC educational resources.

Figure 1. Duke University's portal on Coursera

When Duke first began developing MOOCs, the uptake in creating video lessons immediately suggested the opportunity for instructors to explore flipped classes. By using these instructional videos in place of in-class lectures for campus courses, faculty freed up class time for more engaging activities and provided students greater flexibility in learning content. To date, more than half of Duke's MOOCs have led to at least one flipped class.

However, the on-campus impacts have gone far beyond moving lectures from the podium to the laptop or mobile device. Faculty members are

- leveraging MOOC resources for much-needed supplemental learning and review opportunities for on-campus students,

- improving materials and activities in their classes,

- crafting better assessments to measure student learning, and

- experimenting with new pedagogies to increase engagement and learning.

In this article, we offer various examples of how the MOOCs initiative has led Duke faculty members to evolve in their approaches to teaching and learning.

Finding Diversity in Flipped Classes

Duke faculty members use MOOC videos and other materials to flip their campus classes in a variety of ways — and not always as expected. For example, people often associate flipped courses with seminar-style classes of 25 to 30 students. However, Duke Biology Professor Mohamed Noor successfully flipped Introduction to Genetics and Evolution, a lecture-style class of 450 undergraduates, by having students watch MOOC videos before class and respond to short quizzes. Based on the quiz results, Noor selected subjects that students needed to review and divided students into small groups to work on related problems in class. With help from 19 in-class teaching assistants, Noor spent class time checking in with the small groups of students and further explaining concepts as needed.

Reflecting on the experience, Noor said:

"In a regular lecture, there's no way you could identify misinterpretation, because [students] write it down, and they write it down in their misinterpreted way, and they just keep moving on. Whereas, this way, I catch it before any significant grading is ever done for them, so I can catch it, correct it, and then they can move on understanding it that much better ahead of time."

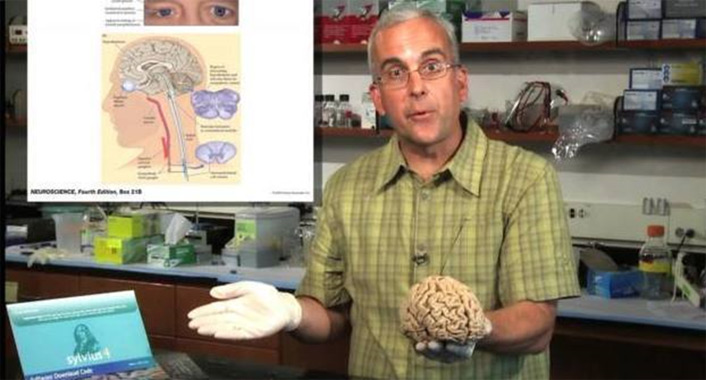

Some Duke MOOCs have even generated multiple flipped and hybrid classes. Medical Neuroscience, a MOOC taught by Duke Institute for Brain Sciences Professor Leonard White, generated videos used to partially or entirely flip seven different classes ranging from introductory-level medical school courses to a course in the neuro-humanities in Duke's Paris-based global education program.

Increasing Access to Learning Opportunities

Another outcome we found surprising was the extent to which MOOCs have led faculty members to increase on-campus student access to online learning materials. These materials help reinforce what students learn in class and let them review difficult material.

For example, students use White's neuroscience videos to prepare for medical board exams and clinical rotations (figure 2). Although many of these students have never even met White, they consider him one of their favorite teachers.

Figure 2. Video still from White's Medical Neuroscience course

In another example, Physics Professor Ronen Plesser created a series of demonstration videos for his Introduction to Astronomy MOOC. He uploaded the videos and makes them available to his on-campus students as well, so they can review complex principles and theories on their own. Plesser has found that students appreciate being able to actually see demonstrations of the theories they are studying while outside of class (figure 3). The videos also let him present content to students through various mediums, which helps students who better understand content from watching videos while letting those who prefer to read use the text. Repurposing the MOOC videos as supplemental materials thus lets Plesser meet the needs of students with diverse learning styles.

Figure 3. Plesser filming a physics demonstration for his astronomy course

Improving Teaching Content

Noor found that his MOOC also led to improvements in the learning materials he offers his students. He noted that the first time he taught his MOOC, it felt like he was getting crowd-sourced feedback on all his materials. MOOC participants were quick to point out errors or unclear elements of the course. As a result, he was able to improve all his course materials, and the experience prompted him to think about new ways to teach on campus. Noor is one of several MOOC instructors at Duke who said they have become more intentional and innovative in the activities and assignments they use on campus as a result of creating and teaching a MOOC.

Creating Better Learning Assessments

MOOCs have led some professors to rethink their approach to assessment as well. In Public Policy Professor David Schanzer's two MOOCs about the history and policy impacts of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Schanzer asks students to write a policy brief, which is a structured and highly specialized writing format.

To facilitate peer assessment — in which MOOC learners review and rate each other's work — Schanzer created a detailed rubric for evaluating a policy brief. This rubric worked well, and the peer assessment was a success. Schanzer then brought the approach back to campus and made detailed grading rubrics for his students there. The undergraduates said the new rubrics help them do a better job on assignments, because they clearly describe each assignment's content and format requirements. Since he introduced the rubrics in his on-campus classes, Schanzer has seen an overall improvement in the quality of student assignments.

Discovering New Teaching Approaches

One of the most exciting impacts of MOOCs on teaching at Duke has been faculty members rethinking their assumptions about how students learn. Writing Studies Professor Denise Comer was initially skeptical that a skill like writing could be successfully taught online; not only had she personally never tried it, but she also didn't know any other professors who had. As an experiment, she developed a writing-intensive introductory English composition MOOC (figure 4). What she found surprised her: not only was it possible to teach writing online, but the students in her MOOC also gave her high praise for the course. One student said:

"I think it was a great idea to give this kind of course! I think it's a course that can help many people in different ways. I love writing but lost the habit of it and thanks to your class — I´m back on track and feel inspired! My peers in the course gave me very good constructive feedback, and I learned to improve."

Figure 4. Comer leading a Google hangout with students in her English Composition course

Inspired by her success teaching writing online, Comer built a new online summer course for Duke undergraduates doing off-campus internships. Her students write blog posts and engage in other online writing activities while attending both synchronous and asynchronous class sessions with Comer over the Internet. The class lets students away from Duke continue to take classes; Comer said she never would have believed the campus class could work until she saw her MOOC students' written assignments.

Another example of how MOOCs have impacted pedagogy at Duke comes from Engineering Professor Guillermo Sapiro, who teaches a technical, challenging MOOC on image and video processing. To ensure that his students mastered the foundational material before moving on to more complex concepts, Sapiro added short quizzes throughout the course. The MOOC students felt that these brief quizzes did an excellent job of helping them assess whether they were ready for more advanced material, so Sapiro decided to incorporate quizzes into his campus class as well. He now gives his undergraduates a short formative assessment each class meeting and uses the results to identify topics he needs to review in the next meeting. Sapiro said that, as a result of his MOOC experience, he is "constantly learning how to improve the Duke class."

Professor David Boyd saw his MOOC, The Challenges of Global Health, as an active learning opportunity for his campus undergraduates. Based on the idea that students learn best when they create content and interact with new material, Boyd asks his on-campus Duke students to participate in the MOOC discussion forums. His students thus can answer questions and have conversations about the course content with MOOC participants from all over the world. The Duke students also help run the live online sessions that Boyd offers periodically during the MOOC and critique the course videos Boyd. These opportunities have pushed Boyd's undergraduates to think about and interact with the material in a deeper way than if they simply watched a video.

The Importance of Trying New Things

Duke University's MOOCs initiative has had an impact in reaching global audiences, increasing access to educational resources, and spurring on the development of new educational technologies and business models. However, one of the MOOC initiative's most important benefits is in affording Duke faculty the freedom and opportunity to try new things. Without a willingness to experiment, our faculty members might not have discovered these ways to improve teaching and learning in their courses.

Duke plans to continue providing its faculty the expansive opportunities provided by MOOCs and other potentially innovative tools and ideas. In this way, our faculty members can continue stimulating our campus conversation about new possibilities in teaching and new ways to improve learning.

© 2014 Kim Manturuk and Quentin M. Ruiz-Esparza. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.