Key Takeaways

- To facilitate IT project success in the challenging higher education environment, trust and collaboration among IT staffers and various campus groups are essential.

- To improve trust and collaboration, the IT staff at Cornell University's Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management consciously set out to create highly productive relationships with the school's departments, faculty, and students.

- The team's experiences and lessons learned can guide both brief and long-term collaborations, as well as daily interactions among IT staffers and customers across an institution.

- Collaboration, design thinking, and innovation go hand-in-hand.

Todd Kreuger, CIO, Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University

To facilitate sustainable success amid the various obstacles in higher education's IT landscape, IT departments must play a key role in driving innovation, transformation, and differentiation within each constituency group on campus. Many such groups embrace technology as the vehicle for organizational success; the key is finding the right technology. Identifying and implementing the appropriate technical solution requires collaboration, fueled by trust, to steer the project to the appropriate end result.

Unfortunately, many projects end up miles away from what the customer needs due to collaboration and trust issues. In some unfortunate cases, such projects — with their associated waste of time and money — end up abandoned. Far too often, when these projects do continue, they achieve less than satisfactory results, including plenty of finger pointing and wasted time, money, and opportunity.

To address this, the Technology Services Department at Cornell University's Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management set out to create a culture of productive, collaborative relationships with our customer departments, faculty, and students. Although we approach each group somewhat differently, our collaborative efforts have proven successful.

"The collaboration that we were able to achieve is pretty incredible," said Christine Sneva, Johnson's former executive director of Admissions and Financial Aid. "The teams in IT and the teams in Admissions didn't feel like two separate teams, they really felt like one — and we work as one."

Achieving this level of collaboration requires the successful creation of trust, as explained in this article.

Trust and Collaboration: IT's Role

In higher education, IT's underlying goal is to help significantly further the institution's mission. Collaboration with stakeholders helps us navigate various needs, obstacles, politics, and constraints and thereby help our customers achieve their goals, while trust facilitates give and take. Once a trusting relationship is established, an open and effective idea exchange is possible, which facilitates a culture of innovation. However, IT professionals all too often focus on technology at the peril of this collaboration and trust. I get it; most IT departments have too much to do given their existing resources. Nonetheless, while the time commitment is sometimes significant, collaboration can help IT teams more effectively gather requirements, which often leads to a shortened delivery cycle and a more favorable end result. Recognizing the importance and benefits of building collaboration and trust, with an associated time and resource commitment, is arguably the first step.

Most of the relationships we built were either dysfunctional or nonexistent when we began our focus on collaboration. As a result, we took a strategic approach to identifying departments with the greatest need and engaged in a fairly lengthy collaborative effort aimed at transformation. Still, many of our guiding concepts and lessons learned are appropriate regardless of the initial working relationship, and they apply to both short- and long-term collaborations as well as daily operational interactions.

Lessons Learned

We learned six key lessons from our collaborative efforts with various constituency groups:

- Get on the same page

- Build and establish trust

- Provide the tools and expectations for success

- Focus on both strategic and operational needs

- Clarify process ownership and the associated responsibilities

- Recognize the desired performance and celebrate success

Here, I describe each of these lessons and how they played out in our experiences at Johnson. My hope in doing so is to inspire other IT departments to prioritize the trust-building and collaboration processes with their own customer groups — and reap the benefits accordingly.

Get on the Same Page

It might sound obvious, but it is critical to have an open dialogue with various customer groups. For example, your initial discussion could be a sit-down meeting, with subsequent drop-ins, meetings, or e-mails as needed. During these meetings and informal interactions, it is critical that you get an accurate assessment of how things are going. Customers must understand that it's hard to fix something when you don't know it is broken. A printer that has not worked for three weeks is just one example of an issue that should be addressed immediately. Actively identifying pain points — as well as items that do not target the customer's actual goals — is an exercise that will help you identify needed operational or process changes.

The frequency of appropriate follow-ups is highly dependent on both the state of the working relationship and the reliability and effectiveness of technology implementations. Identifying and initiating the process to have appropriate IT Team members address outstanding issues (such as a broken printer) will allow you to focus on how technology can be an engine for making a real difference.

As you wend your way from customers viewing IT staff members as reactive problem solvers to becoming proactive strategic partners that help the institution stand out against its peers, you change IT's image and value, which can positively impact staffing and resource requests.

When meeting with customer groups, a simple statement such as the following can illustrate your intentions; it might even elicit a laugh:

"Our goal is to exceed your expectations. I realize we may need to meet them first. So, we're going to do everything we can to meet and then exceed your expectations."

I have yet to encounter a customer who argues with that goal. In fact, faculty and others who were initially skeptical about it have told me in follow-ups that they actually have seen a significant change.

My initial meetings with departments are with the department or division head. When widespread issues exist, I also hold a meeting with the entire department, faculty, or student group and clearly convey the goal of exceeding expectations and outline what that process will entail. I also share my contact information, including my cell phone number, as well as that of other appropriate IT leaders.

The next challenge is to ensure that people recognize the past as the past and not as an indicator of future performance. Institutional memories are quite long; the fact that someone "tried this same thing 12 years ago to no avail" will likely be communicated. The best way to begin a change in culture is to identify issues and challenges that you can immediately address for some quick wins. One approach is to partner with naysayers or the most vocal customers.

To counter a coworker who said, "This is never going to get better because …," I first scheduled a meeting six months in the future to discuss whether or not things had improved. In the meantime, I worked with him on what had to be done and spelled out the desired end result. As scheduled, we met in six months; to his amazement — and by his own admission — things had actually gotten better.

Build and Establish Trust

The reservoir of trust is built one action at a time and emptied in a hurry. To steadily build trust, you must say what you are going to do and do what you say. Communication is the heart and soul of trust. It is imperative that you ask appropriate questions and listen to gain understanding.

Setting expectations is critical, but it is not the expertise of most IT departments. At times, it might be easy to say you will address a specific technical issue or project within a given amount of time, but often neither the issue nor how long resolving it will take is totally clear. In those instances, you must convey what the customers can expect to see by a given date. For example, you might tell the customers that you need to investigate options and will get back to them with a better plan by a specific date (such as a week or a month in the future). Most customers want to understand the timeline and have no problem giving you reasonable time to complete a task. Of course, some projects have a due date, which you should ascertain by asking specific questions. Regardless, when setting expectations, it is critical that all parties agree to the timeline.

Follow up and follow through are also key. When you cannot meet agreed upon deadlines, reset the expectations as soon as possible and be sure to meet the revised deadline.

Establishing a bedrock of trust is critical to every aspect of collaboration. Without trust, constituents will assume we don't want to help them, don't care, and are just pawning our work off on them or someone else. Once we establish trust, customers know we are looking out for them, and finger pointing is replaced by camaraderie as we work together to solve problems and advance the institution.

Provide the Tools and Expectations for Success

We all know how easy and common it is to blame IT. In some cases, the blame might be apt; in other cases, customers might not have the expertise and tools required to understand whether the issue is a technical one or not. It is our responsibility to provide the guidance and training necessary for customers to perform appropriate due diligence on their own. This is particularly true with data-driven departments. Data and reporting errors are often caused by business process anomalies.

Establishing a common language and defining the severity of different types of issues is critical to collaboration efforts. To some departments, data and stats are priority one, while others focus on the satisfaction of their customers (for example, the students).

E-mail is an often-overused tool when working through issues, and it sometimes resembles a game of hot potato. When it comes to working through and fixing the issues, 30-thread e-mails are often about as effective as finger pointing.

As much as e-mail is overused, phone and informal, in-person meetings are often underused, especially during the initial trust-building phase of a relationship. Johnson Technology Services employees are encouraged to call or meet in person when an issue must be addressed and e-mail communication is not producing the desired results in a timely manner.

When excellence is achieved, it feeds on itself and can become the norm. The key is not only to ensure that expectations are clear but also that roadblocks and obstacles are replaced by the tools and vision of success.

Focus on Strategic and Operational Needs

It is critical to have a game plan to address various issues and needs. When working with some departments, a single group of individuals can collaborate to address both operational and strategic issues, whereas other departments require a two-pronged approach. In the latter case, our technical personnel attend department operations meetings on a regular basis.

These operations meetings offer a means for in-depth conversation on specific reporting and other system needs. They also ensure that IT personnel are present when other pain points are discussed. This lets our team better understand a department's business needs, which facilitates design thinking. Because we figuratively sit in the chair of those using the technology, we come up with better, more efficient ways to do things. We can also toss ideas back and forth in a highly collaborative and innovative environment, which leads to significant operational and technology changes. Finally, working closely with people on issues makes it harder to point fingers later.

In one case, our developers were diving into the details and having great success doing so; simultaneously, Johnson IT leaders met with the department's director to discuss the department's high-level strategic needs. These meetings included candid assessments of the current state and vision for the future, as well as plenty of give and take on the solutions and timeline for completing the projects.

Sneva characterizes the collaborative process as follows:

"I would just get leading questions about needs and what we really needed and what we really wanted. And it was sort of like this onion that we were just constantly trying to unlayer a little bit here to really get at what we really needed."

Regardless of whether you take a two-pronged approach or have a single defined group that works through issues together, it is critical to document your decisions. Action items, ownership, and deadlines must be documented, and follow up must occur in each meeting (at a minimum).

Clarify Process Ownership and Associated Responsibilities

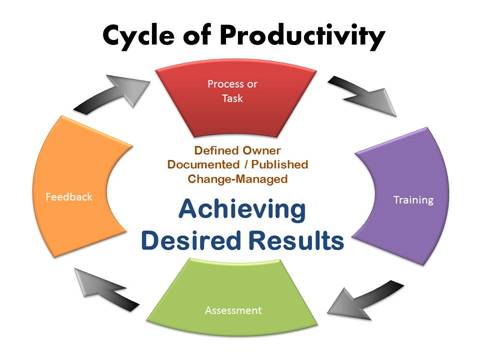

Many of our customers' data-related problems are caused by a business process failure of some kind. It is not uncommon for a few staff members to get together in a vacuum and decide to change a business process, which results in changes to the reports or the associated data. To address these issues, we use what I call the Cycle of Productivity model (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The Cycle of Productivity model

The initial takeaway? Processes and tasks must have a defined owner and be documented and published, and change must be managed to ensure that everyone is aware of the new expectations. Although a detailed review of the model is beyond the scope of this article, the basic premise is that training, assessment of effectiveness, and feedback all must occur to ensure the process or task is completed as expected. The assessment, for example, aims to understand the effectiveness of the

- training,

- person doing the task, and

- process or task itself.

It is telling that many IT managers often spend more time developing a process or task than they do ensuring that it is carried out appropriately and actually meets the intended and desired objective.

Recognize the Desired Performance and Celebrate Success

Focusing considerable time and attention on things that don't go as expected is all too common in IT. Of course, we must fix what is broken, and providing coaching and direction is required and beneficial — assuming it is done properly. That said, I've found that I get much more mileage out of recognizing and celebrating the desired behavior and the wins.

When customers understand that you are trying to exceed their expectations, they are often quick to send a congratulatory e-mail. This is an excellent opportunity to reinforce the desired behavior with staff members; I send such e-mails both to the employee who provided the service or performed the task/project and to my boss. I also read them in department meetings. When kudos are related to collaboration efforts, the e-mails can be read in inter-team meetings or at the celebrations when a project culminates.

Conclusions

Collaboration should not be a project in and of itself, but rather it must be woven into all aspects of how we do IT. We must collaborate with

- our customers, to help them address their strategic and operational objectives;

- other staff members throughout IT; and

- thought leaders in specific fields.

We live in a world where we can and should engage people with expertise on a variety of topics to better understand the issues, customer needs, and possible solutions related to any challenge.

As Verne Thalheimer, senior director of Operations for Executive MBA Programs at Johnson, notes, serious challenges can be overcome through effective collaboration:

"When I started [more than] three years ago, the level of communication and collaboration between IT and Executive MBA Programs needed significant attention to improve the student experience. By implementing a regular series of meetings, plus ongoing collaboration, we made huge strides in very short order. What had been a problem area for us quickly became one of the strongest facets of our program delivery."

The ideal end game, which I have witnessed firsthand with multiple constituent groups at Johnson, is one in which a culture of collaboration, coupled with a relentless focus on challenging the status quo, results in our encouraging, pushing, and helping each other innovate, transform, and differentiate.

© 2015 Todd M. Kreuger. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.