Key Takeaways

- Surveys of 11 MITx courses on edX in spring 2014 found that one in four (28.0 percent) respondents identified as past or present teachers.

- Of the survey respondents, nearly one in 10 (8.7 percent) identified as current teachers.

- Although they represent only 4.5 percent of the nearly 250,000 enrollees, responding teachers generated 22.4 percent of all discussion forum comments.

- One in 12 of the total comments were made by current teachers, and one in 16 were from teachers with experience teaching the subject of the MITx course in which they enrolled.

Daniel Seaton, Research Analyst, and Jon Daries, Senior Research Analyst, Institutional Research Group, Office of the Provost; Cody Coleman, Graduate Student, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science; Isaac Chuang, Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Department of Physics, and Office of Digital Learning, MIT

Participants in massive open online courses (MOOCs) come from a diverse set of backgrounds and act with a wide range of intentions.1 Interestingly, our surveys of 11 MITx courses on edX in spring 2014 show that teachers (versus traditional college students) make up a significant fraction of MITx MOOC participants. This suggests different ways to improve MOOCs:

- harnessing the potential arising from participants' collective professional experience,

- facilitating educator networks,

- creating opportunities for expert-novice interactions,

- enhancing teacher experiences through accreditation models, and

- enabling individual teachers to reuse of MOOC content.

Here, we present data in detail from these teacher enrollment surveys, illuminate teacher participation in discussion forums, and draw lessons for improving the utility of MOOCs for teachers.

MOOCs Past and Present

One of the earliest precursors to modern MOOCs targeted high school teachers in the United States. In 1958, a post-war interpretation of introductory physics called "Atomic-Age Physics" debuted at 6:30 a.m. on the National Broadcasting Company's (NBC) Continental Classroom. Daily viewership was estimated at roughly 250,000 people,2 and over 300 institutions partnered to offer varying levels of accreditation for the course. Roughly 5,000 participants were certified in the first year.3 Teachers were estimated to be 1 in 8 of all certificate earners,4 indicating reach beyond the target demographic of high school teachers. Through its expansion of courses between 1958 and 1963, the Continental Classroom represented a bold approach in using technology to address national needs in education reform. In contrast, the current MOOC era has largely focused on student-centric issues like democratizing access5.

Nevertheless, a few scholars have reaffirmed the tremendous potential for engaging teachers within the current MOOC movement. Douglas Fisher highlighted the sense of community emerging from the "nascent and exploding online education movement," while summarizing his perspective on using MOOC resources from another university in his classes.6 Others have begun to recognize the substantial role that MOOCs could play in reforming teacher professional development.7 More pragmatically, Samuel Joseph described the importance of community teaching assistants (TAs) within edX, along with his own efforts to support and organize contributions of more than 250 volunteer TAs in a single MOOC.8

MOOCs are generating unprecedented dialogue about the current state and future of digital education,9 and interest clearly goes beyond typical scholars studying education. One might even argue that MOOCs are an ideal hub for hosting enthusiastic educators to discuss, refine, and share pedagogy. Paramount to achieving this goal is a simple question: Are a substantial number of educators already enrolling in MOOCs?

Enrollment Surprises in MITx courses on edX

At MITx (MIT's MOOC organization), early MOOC experiments have indicated that teachers are indeed enrolling. The MITx course known as 8.MReV: Mechanics Review, which derived from an introductory on-campus physics course at MIT, was initially advertised as a challenging course for high school students. On completion, however, course staff recognized that high school teachers were an active contingent.10 In response, the course team partnered with the American Association of Physics Teachers to offer continuing education units in subsequent offerings.

A widely covered anecdotal example of teacher enrollment involved the inaugural MITx course, 6.002x: Circuits and Electronics. An MIT alumnus teaching electrical engineering to high school students in Mongolia enrolled in the course alongside his students. He used the online content to flip his classroom, asking his students to complete all assignments related to the 16-week course. This experiment led to one exceptional student from his class being admitted to MIT in 2013.11 Such an example raises questions regarding how many other teachers, not just alumni, might be using similar strategies without the knowledge of MOOC providers.

These limited examples signal that an important demographic may be hidden from MOOC providers and course developers. If a substantial number of teachers indeed enroll in MOOCs, the educational possibilities are considerable: expert-novice pairings in courses, networking educators around pedagogy or reusable content, and generally tailoring courses to satisfy the needs of teachers. In response to these initial, anecdotal findings, we used a systematic survey protocol to address specific questions related to teacher enrollment, their backgrounds, and their desire for accreditation and access to materials to use in their own courses.

Survey Methodology and Forum Analysis

In the spring of 2014, entrance and exit surveys addressing the motivations and backgrounds of participants were given in 11 MITx courses. Although these surveys addressed multiple issues concerning participants, teacher enrollment was a significant concern with questions addressing the following broad themes:

- Are a significant number of teachers enrolling in MITx open online courses?

- If so, do these teachers come from traditional instructional backgrounds?

- Do teachers completing a course desire accreditation opportunities and broader usability of MITx resources?

Over 33,000 participants responded to the entrance surveys, which focused largely on themes 1 and 2. The exit surveys had over 7,000 respondents, with questions addressing theme 3 for current teachers. The survey questions used to address these broad themes can be found in supplementary material.

In addition to survey data, a tremendous amount of participant interaction data is available. Discussion forums entries and click-stream data allow checking whether participating teachers are actively pursuing an important aspect of their profession, namely, instructing other participants within a course. Using the responses to the entrance surveys, we can compare the behavior of teachers versus non-teachers.

Entrance Survey

Entrance surveys of over 33,000 participants in 11 MITx courses on edX from the spring of 2014 reveal a substantial number of enrolling teachers. The questions identified three categories: past or present teachers, current teachers, and teachers with experience teaching the course's topic. (These categories are not mutually exclusive.) Table 1 provides totals and average percentages across courses relative to survey respondents.

Table 1. Results of surveys of teacher enrollment, spring 2014

|

Course |

Registrants by Week 3 |

Number Surveyed |

Identify as Teachers |

Current Teachers |

Teach Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

21W.789x: Mobile Exp. |

31,072 |

4,217 |

933 |

242 |

115 |

|

6.041x: Intro. Probability |

26,569 |

2,400 |

553 |

197 |

116 |

|

12.340x: Global Warming |

13,047 |

2,458 |

956 |

318 |

277 |

|

6.00.1x: Comp. Sci. Part 1 |

22,797 |

3,997 |

956 |

280 |

280 |

|

15.071x: Analytics |

26,530 |

3,010 |

838 |

183 |

122 |

|

6.00.2x: Comp. Sci. Part 2 |

15,065 |

2,997 |

739 |

216 |

123 |

|

16.110x: Aerodynamics |

28,653 |

1,709 |

441 |

139 |

86 |

|

15.390x: Entrepreneurship |

44,867 |

4,843 |

1,682 |

405 |

268 |

|

6.SFMx: Street-Fighting Math |

23,640 |

4,162 |

1,364 |

499 |

333 |

|

3.091x: Solid-State Chem. |

6,954 |

1,639 |

506 |

195 |

144 |

|

2.01x: Structures Eng. |

7,705 |

2,058 |

483 |

173 |

144 |

|

Total |

246,899 |

33,490 |

9,451 |

2,847 |

1,871 |

|

Average Percentage of Survey Respondents |

— |

16.8 |

28.0 |

8.7 |

5.9 |

Cross-course averages indicate 28.1 percent of respondents identify as past or present teachers, while 8.8 percent identify as current teachers, and 5.9 percent have taught or currently teach the course subject. Note, these percentages are even more striking when enumerated. Across all survey respondents, there are 9,628 self-identifying teachers, 2,901 practicing teachers, and 1,909 participants who have or currently teach the topic. The average survey response rate was 16.9 percent, meaning that if respondents were a random sample of registrants, the actual numbers of teachers would be approximately six times larger. Although teachers are likely to respond at greater rates, we argue that the baseline numbers are themselves numerically significant.

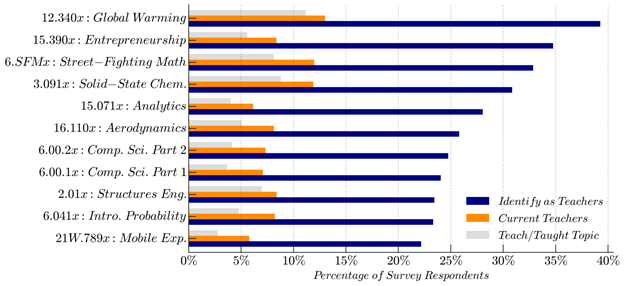

Figure 1 shows the percentage of self-identifying teachers, whether they have or currently teach the course topic, and the percentage of currently practicing teachers. Percentages are relative to the number of survey respondents.

Figure 1. Enrolled teacher characteristics among survey respondents

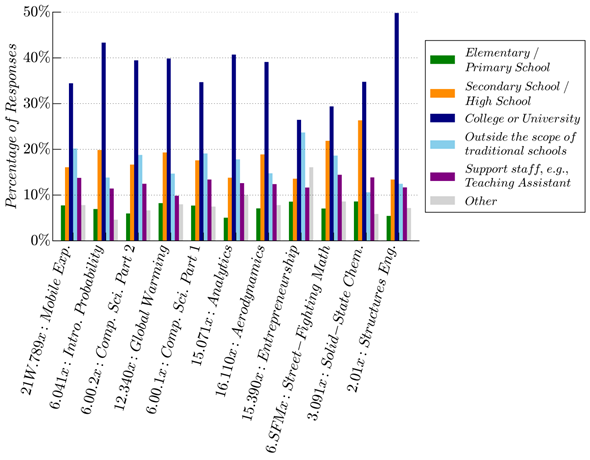

The entrance surveys also included questions contextualizing respondents' instructional backgrounds. Figure 2 contains distributions of response options, where 73.0 percent of responses indicate what we consider traditional teaching backgrounds: Primary/Secondary School, College/University, or Support Staff, such as Teaching Assistant. A notable exception is Entrepreneurship (15.390x), which has only 60.2 percent of respondents with traditional teaching backgrounds (also see supplementary material). The course topic may offer a signal that explains the variation of teacher enrollment across courses. One can make alternative arguments that the large enrollment in Global Warming (12.340x) and Street-Fighting Math (6.SFMx) may be partially explained by interest of teachers in seeing materials and alternative views on instruction.

Figure 2. Instructional context of self-identifying teachers

Taking a closer look at the breakdown of instructional backgrounds as seen in figure 2, College or University teachers account for the largest populations, but may range from faculty to teaching assistants. The size of the College or University population is likely due to all surveyed courses being college level. K–12 teachers make up 25.0 percent of instructional context in figure 2 (found by summing the Primary School and Secondary School categories). The categories "Outside the scope of traditional schools" and "Other" indicate respondents who consider themselves teachers outside the available choices within the survey (see supplementary material). Free-response submissions were allowed within the "Other" category, and a number of respondents identified as tutors or working in corporate training. The survey question allowed for multiple responses. All percentages in figure 2 are relative to the total number of responses within each course. Each category provides a number of hypotheses for "who" enrolls in these courses, but future work must dig deeper into "why."

Exit Survey

Within the last two weeks of each course, questions related to teachers were added to exit surveys to assess the course impact on teachers and determine whether course developers were missing opportunities to provide professional development and accreditation for participating teachers. Of 7,149 survey respondents, 1,002 (15.6 percent) again identified as current teachers and answered questions pertaining to accreditation, course influence, and use of MITx MOOC resources. Across all 11 MITx courses on edX, an average of 53.9 percent (560) of current teachers answered "yes" to having interest in accreditation opportunities, while 15.1 percent answered "no" and 26.4 percent answered "unsure" (see supplementary material). Greater than 70 percent of responding teachers slightly-agree or strongly-agree they will use MITx material in their current teaching, and greater than 70 percent would be interested in using material from other courses. Even so, many MOOC providers have yet to adopt open educational resource (OER) models aimed at facilitating content sharing.12

Discussion Forum Analysis

Each MITx MOOC employed a threaded discussion forum to support enrollee interactions. Any participant can contribute written content, and it is of central interest whether teachers actively engage with other participants. Forum data collected by the edX platform allow us to monitor such activity in the form of three allowed interactions: "posts" initialize a discussion thread, "comments" are replies within those threads, and "upvotes" allow users to rate a post or comment. Comments are often generated as a response to help-seeking, representing an interaction that a teacher would be well suited to undertake. We focus on comments below, noting that similar analyses applied to posts were nearly identical.

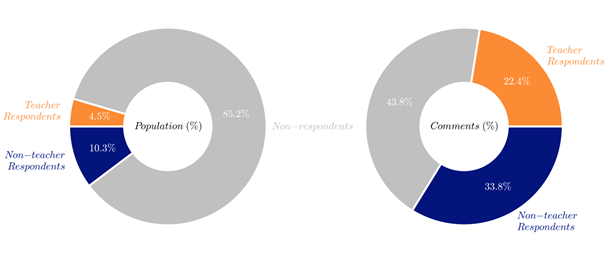

One way of framing teacher behavior in the forums is simply counting their total number of textual contributions relative to all participants, i.e., the likelihood of a participant receiving a comment from a teacher. For all participants — teacher respondents, non-teacher respondents, and non-respondents — a total of 57,621 comments were generated across all 11 MITx courses. Figure 3 highlights the percentage of comments relative to population sizes. Despite representing only 4.5 percent of the total population, teacher respondents generated 22.4 percent of all comments. Non-teacher respondents generated 33.8 percent of total comments, but were twice as large a population (10.3 percent). All other participants (non-respondent) generated 43.8 percent of total comments, but made up 85.2 percent of the population. More notably, 1 in 5 comments were written by survey-responding teachers, 1 in 12 were by a current teacher, and 1 in 16 were by teachers who teach or have taught the subject. It must be noted that MITx course staff did not advertise to attract teachers, nor did they offer special consideration for their contributions to a course.

In addition, we have also analyzed distributions of posts, comments, and overall discussion activity to search for statistically significant trends between teacher and non-teacher respondents. The mean number of discussion comments by teacher respondents is statistically higher than non-teacher respondents in 4 of 11 courses (see supplementary material), but not statistically distinguishable in the others. We note that distributions of forum activity are often highly skewed, typically due to only a few users contributing the majority of text.13 For example, course staff members designate community TAs to moderate discussion forums, and they generate a tremendous amount of textual contributions.14 Of the 15 participants assigned this duty within the 11 MITx courses studied here, 10 took the entrance survey, 5 of whom identified as teachers.

Finally, we note that trends found through analysis of posts — initiating a discussion thread — are nearly identical to those found for comments. This implies that teachers do not reserve their forum behavior to replies in threads, but are also actively initializing discussion (see supplementary material).

Figure 3 (left) shows the average percentages of enrollees who were teacher respondents, non-teacher respondents, and non-respondents across MITx courses on edX in the spring of 2014. The right half of figure 3 shows the average percentage of comments across courses that the aforementioned groups made. Although survey respondents identifying as teachers represent only 4.5 percent of the overall population (left), they generate 22.4 percent of all comments (right). Categories are based on the entrance survey.

Figure 3. Average percentages of enrollees by category (left) and average percentage of comments by

group (right)

Discussion

Survey results implied several discussion-worthy topics: networked instruction for courses to empower teacher enrollees; professional development for teachers; and provision of the MOOC materials to educators for reuse in their own teaching.

Implications for Courses

Teacher enrollment and participation have implications for platform design in terms of how educators network with other participants. Forums could be optimized to promote expert-novice dialogue, while novel assessment types such as peer grading could use participant profile information in assigning graders.15 In addition, platforms could provide tools that allow teachers to discuss specific content or pedagogy, while simultaneously contributing feedback to course staff. The collection and maintenance of profile information will be crucial, with questions remaining for platform designers on whether such information should be collected publicly (e.g., LinkedIn for MOOCs) or privately (surveys). Public and private data collection issues are particularly relevant considering the recent discussion of student privacy in MOOCs.16

Teacher enrollment also has implications for course design, where participating teachers could begin taking on aspects of group discussion or tutoring sessions within a course. A recent experiment in the HarvardX course on copyright has begun experimenting with such ideas using cohorting tools to divide participants into small-enrollment sections, each led by a Harvard Law School student.17 When considering worldwide enrollment in MOOCs, it makes sense that teachers from specific cultural backgrounds could lead students from their own regions. Within any model of networked instruction, consideration of the impact on both teachers and students should be taken into account.

Implications for Teachers: Professional Development

Teacher professional development18 is an ongoing focus of federal educational policy.19 A recent report from the Center for Public Education emphasized that educational reform movements for students like the Common Core Standards require equal reform for teacher professional development.20 Key issues include moving away from one-day workshops, delivering professional development in the context of a teacher's subject area, and developing peer (or coaching) networks to facilitate implementation of new classroom techniques.

Already, MOOCs directly related to professional development are emerging.21 Among others, Coursera has launched a "teacher professional development" series serving the pedagogical needs of a variety of educators, and edX has just announced a professional development initiative focusing on advanced placement high school courses. Nonetheless, the huge catalogue of available courses raises the question of whether professional development should be provided within the context of a specific topic. For example, a 2009 survey indicated that only 25 percent of high school physics teachers were physics majors.22 Because of the tremendous amount of content produced for MOOCs, it seems possible that teacher training could leverage this technology within a Pedagogical Content Knowledge framework.23

Providers will face challenges in addressing the broad meaning of accreditation and professional development in regard to worldwide access and the diversity of teacher backgrounds.24 In the United States, MOOC participation will also need to be defined in the context of current accreditation models. Costs of continuing education units are often charged by contact hours in workshop formats taking place over one to two days; how does one translate a 16-week MITx course where mean total time spent by certificate earners is 100 hours?25 However, exploring this issue may help MOOC providers identify potential revenue models; spending estimates for professional development in the United States range between $1,000 and $3,000 per teacher per year.26

Teacher Utilization of MOOC Resources

One of the central themes of the teacher survey respondents is a strong desire to use the MITx course materials in their own teaching. This suggests that ideally, teachers could employ a personalized sub-selection of a given MOOC's assessment problems, text, and video content and provide this with their own schedule of material release and due dates, synchronized with their own classrooms schedules, and in harmony with local curricula. Moreover, perhaps ideally, teachers could also enroll their own cohort of students and be able to see their students' progress and scores. In such an environment, students would likely benefit from being able to discuss the content in the personalized, teacher-defined cohort of individuals.

Unsurprisingly, however, MOOC platforms like edX were not designed to work this way. On the other hand, the Khan Academy does offer a coaching functionality, which provides essentially all these ideal capabilities to successfully engage teachers. This presents an excellent model that MOOC providers might emulate.

In many ways, what MOOCs need is mechanisms to easily transform into "personal online courses," dropping the "massive" and "open," to enable teachers to become a strong point of contact between students and the potentially rich content of MOOCs. Such personal online courses could also serve as natural stepping stones to transforming the digital learning assets of MOOCs into open educational resources, opening doors not just to reuse but also collaborative authoring and "social coding" of course content by teachers building off each other's work.

Summing Up

Teachers are heavily enrolled and engaged in MITx courses on edX, and evidence indicates that they play a substantial role in discussion forums. Measuring the current impact of teachers on other participants is an important area for future research, and one that might help develop learning frameworks that better partner teachers with course staff and other participants. Teachers' motivations in taking a MOOC will play a key role, whether they are engaging in life-long learning, pursuing life-long instruction, or searching for new pedagogy and peer support. Regarding pedagogy and peer support, adoption of new teaching practices is a major challenge facing teachers and school districts in the United States.27 MOOCs targeting the needs of teachers and providing mechanisms to become personal online courses can potentially provide a space for educators to overcome adoption barriers and a sustainable foundation for MOOCs' continued existence.

Teacher enrollment clearly represents an unrecognized, meaningful audience for MOOC providers. Recent reports have largely focused on demographics within MOOCs,28 even leading to criticism that the typical participant is older and holds an advanced degree.29 Recognizing the significance of large teacher enrollments in MOOCs may shift perspectives toward course design and MOOC platform capabilities more attuned to expert participants. We believe teacher participants in MOOCS are a resource to respect and value, with the potential of further enriching the MOOC experience for participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Institutional Research group at MIT, the Office of Digital Learning at MIT, and the HarvardX Research Committee for their support.

- Gayle Christensen, Andrew Steinmetz, Brandon Alcorn, Amy Bennett, Deirdre Woods, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, "The MOOC Phenomenon: Who Takes Massive Open Online Courses and Why?" (November 6, 2013), posted on Social Science Research Network; and Andrew Dean Ho, Justin Reich, Sergiy O Nesterko, Daniel Thomas Seaton, Tommy Mullaney, Jim Waldo, and Isaac Chuang, "HarvardX and MITx: The First Year of Open Online Courses, Fall 2012-Summer 2013," (January 21, 2014), posted on Social Science Research Network.

- R. H. Randall, "A Look at the ‘Continental Classroom,'" American Journal of Physics, 28 (3) (1960): 263–269; A. L. Lacey, "‘Continental classroom' and the small science department," Science Education, 43 (5) (1959): 394–398; John J. Kelley, "A preliminary report on the evaluation of continental classroom," Science Education, 46.5 (1962): 468–473; and Robert D. Carlisle, College Credit Through TV: Old Idea, New Dimensions (1974).

- Ronald Gross and Judith Murphy, Learning by Television (1966); and Carlisle, "College Credit Through TV."

- Kelley, "A Preliminary Report."

- Anant Agarwal, "Online Universities: it's time for teachers to join the revolution," The Guardian, June 15, 2013.

- Douglas H. Fisher, "Warming up to MOOCs," Chronicle of Higher Education, Blogs, November 6, 2012.

- Glen M. Kleiman, Mary Ann Wolf, and David Frye, "The Digital Learning Transition MOOC for Educators: Exploring a Scalable Approach to Professional Development," White Paper (September 2013); and W. Jobe, C. Östlund, and L. Svensson, "MOOCs for Professional Teacher Development," Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference , Vol. 2014, No. 1 (March 2014), 1580–1586.

- Samuel Joseph, "Supporting Communities of Teaching Assistants (TAs) and Students in MOOCs," edX blog (November 13, 2013).

- Laura Pappano, "The Year of the MOOC," New York Times, November 2, 2012.

- Colin Fredericks, Saif Rayyan, Raluca Teodorescu, Trevor Balint, Daniel Seaton, and David E. Pritchard, "From Flipped to Open Instruction: The Mechanics Online Course," Sixth Conference of MIT's Learning International Network Consortium (2013).

- Laura Pappano, "The Boy Genius of Ulan Bator," New York Times, September 13, 2013.

- Chris Parr, "US MOOC platforms' openness questioned," Times Higher Education, April 4, 2013.

- Jonathan Huang, Anirban Dasgupta, Arpita Ghosh, Jane Manning, and Marc Sanders, "Superposter behavior in MOOC forums," Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@scale conference, ACM (March 2014), 117–126.

- Joseph, "Supporting Communities of Teaching Assistants (TAs) and Students in MOOCs."

- Chris Piech, Jonathan Huang, Zhenghao Chen, Chuong Do, Andrew Ng, and Daphne Koller, "Tuned models of peer assessment in MOOCs," paper presented at the Sixth International Educational Data Mining Conference (2013).

- Jon P. Daries, Justin Reich, Jim Waldo, Elise M. Young, Jonathan Whittinghill, Andrew Dean Ho, Daniel Thomas Seaton, and Isaac Chuang, "Privacy, anonymity, and big data in the social sciences," Communications of the ACM, 57(9) (September 2014): 56–63.

- William W. Fisher III, "HLS1X: CopyrightX Course Report," HarvardX Working Paper Series No. 5, (January 21, 2014).

- Charalambos Vrasidas and Gene V. Glass, (Eds.) Online professional development for teachers (Information Age Publications, October 30, 2004).

- William H. Schmidt, Richard Houang, and Leland S. Cogan, "Preparing future math teachers," Science, 332 (603) (June 10, 2011): 1266–1267; and Johannes Bauer and Manfred Prenzel, "European teacher training reforms," Science, 336 (6089) (June 29, 2012): 1642–1643.

- Allison Gulamhussein, "The Core of Professional Development," [http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Staffingstudents/Teaching-the-Teachers-Effective-Professional-Development-in-an-Era-of-High-Stakes-Accountability/The-Core-of-Professional-Development-ASBJ-article-PDF.pdf] American School Board Journal, 197 (1) (July/August 2013): 22–26.

- Kleiman, Wolf, and Frye, "The Digital Learning Transition MOOC for Educators."

- Susan White and Casey Langer Tesfaye, "Who Teaches High School Physics? Results from the 2008–09 Nationwide Survey of High School Physics Teachers," Statistical Research Center of the American Institute of Physics (November 2010).

- Lee S. Shulman, "Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching," Educational researcher, 15 (2) (February 1986): 4–14.

- Bauer and Prenzel, "European teacher training reforms."

- Daniel T. Seaton, Yoav Bergner, Isaac Chuang, Piotr Mitros, and David E. Pritchard, "Who does what in a massive open online course?" Communications of the ACM, 57 (4) (April 2014): 58–65.

- Jobe, Östlund, and Svensson, "MOOCs for professional teacher development."

- Elizabeth Green, "Why Do Americans Stink at Math?" New York Times Magazine, July 23, 2014.

- Christensen et al., "The MOOC Phenomenon"; and Ho et al., "HarvardX and MITx."

- Ezekiel J. Emanuel, "Online education: MOOCs taken by educated few," Nature, 503 (7476) (November 21, 2013): 342.

© 2015 Daniel T. Seaton, Cody A. Coleman, Jon P. Daries, and Isaac Chuang. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.