Key Takeaways

- Small, undergraduate liberal arts colleges can take advantage of technologies used in massive open online courses offered by larger research universities to create small, private online courses.

- Colgate University designed a SPOC using MOOC technologies with the goal of engaging students and alumni through interactive online activities.

- Students who used the interactive capabilities of the course demonstrated engagement with the course materials, answered comprehension questions that affected their test scores, and developed relationships with alumni online.

- Alumni who participated in the course's online activities reported feeling reconnected with their alma mater through their involvement in the course's academic setting.

Declared "The Year of the MOOC," 2012 saw expansion and heightened interest in massive open online courses offered by top-tier research universities.1 Despite focusing on a wide variety of topics, all MOOCs share several features: open and free registration, publicly shared curricula, social networking mechanisms, and facilitation by leading experts in the field.2 To date, the expense and intensive labor necessary to design, implement, and support a MOOC have meant the institutions most suited for MOOC production are large, research-based universities. Small, undergraduate liberal arts colleges, in contrast, do not have the same resources.3 Consequently, liberal arts colleges have not been major players in the MOOC movement to date.

Furthermore, liberal arts colleges emphasize high faculty-student ratios, the expectation of time-intensive student-faculty interactions, and more hands-on teaching styles. Small liberal arts colleges also often have a loyal alumni community that is strongly motivated to engage with the students and can serve as an invaluable educational resource for them. The effective integration of alumni into the campus community often has multiple additional benefits for the institution.

The fundamental philosophical and practical differences between small undergraduate liberal arts colleges and major research institutions raise important questions regarding the use of online educational technology; in particular, how can online platforms benefit students in a liberal arts setting, and how can MOOC technology serve the liberal arts institution? In this article, we describe an experiment conducted at Colgate University (table 1) adapting MOOC technologies and methodologies to enhance connections between Colgate students and alumni, and to construct a learning environment compatible with the ideals of a small college.

Table 1. About Colgate University

| Colgate University | |

|---|---|

|

History |

Founded in 1819 Noted for its Liberal Arts Core Curriculum, which began in 1928 |

|

Location |

Hamilton, NY |

|

Faculty |

303 (All courses are taught by faculty members) |

|

Students |

2, 918 (9:1 student-to-faculty ratio) |

|

Average Class Size |

17 students |

|

Specialties |

54 majors with 9 additional minors 25 Division I athletic teams |

Online Course Initiatives

Colgate University ran its first online experiment in 2014. Further experiments with online educational technology took place in 2015.

First Online Experiment: 2014

The Advent of the Atomic Bomb course ties together the scientific foundations of atomic theory with the social, political, and environmental impacts of the first atomic weapons. Since 1998, co-author Professor Karen Harpp, a member of the Geology and Peace & Conflict Studies faculty, has supplemented this course by having students engage in online discussions with Colgate alumni. She intended the inclusion of alumni participants specifically to infuse the course with a broader set of perspectives than possible with a classroom of 18-to-20 year olds — an essential addition given the historical nature of the course's subject matter. Alumni contributions to discussions about nuclear weapons, Cold War culture, and World War II's impacts are invaluable; many have first-hand memories of these eras, have worked in immediately relevant political, technological, or military fields, or have relatives who participated in the war effort.

Before 2014, the only aspect of the class in which alumni could participate was the online discussion component; they had no access to any other parts of the course, which all took place on campus for current Colgate students. In 2014, in collaboration with Colgate's Information Technology Services, Harpp produced a SPOC — a small, private online course — using the open edX platform. Despite sharing features similar to MOOCs, SPOCs are only open to hundreds of online learners rather than thousands,4 or, in this case, exclusively to Colgate alumni. (For more information about the logistics of the courses, please see table 2.) The SPOC model was integral to accomplishing Harpp's goals for the online course:

- Forging connections between alumni and students;

- Enhancing the learning experience of in-class students; and

- Providing alumni with intellectual content related to the course.

Approximately 400 Colgate alumni enrolled in the SPOC, which was advertised primarily via social media (Facebook, Twitter, and e-newsletters from the Colgate Communications office).

Table 2. Logistics of the course, divided by type of participant

|

Alumni |

Students |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Tuition Costs |

None |

$60,145 per year, 8 courses on average |

|

Length of Course |

15 weeks |

15 weeks |

|

Course Objective |

To provide historical and personal perspectives on course content, foster connections with current students, and engage with their alma mater. Also, to learn about the social, political, historical, and scientific foundations and impacts of the first atomic weapons. |

To learn about the social, political, historical, and scientific foundations and impacts of the first atomic weapons. This course satisfies a requirement of Colgate University's Liberal Arts Core Curriculum. |

|

Assessment Mechanisms and Learner Tracking |

None |

One midterm and one final exam. Several short papers throughout the semester. A major final project focused on implications of nuclear weapons. Participation in the Twitter Project and required weekly postings to the Discussion Board. |

|

Credits Earned |

None |

1 (1 class = 1 credit) |

|

Prior Knowledge |

None required. Instructor reviewed all necessary background information. |

None required. Instructor reviewed all necessary background information. |

The pilot experiment, called an "interactive online experience," lasted 15 weeks. Five online activities were implemented to enhance alumni engagement with the students and with the material.

- First, the course content was uploaded to edX in the form of 30–50-minute illustrated videos, delivered by Harpp and a retired Air Force colonel and docent at the Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. On-campus students received the same information in class, but delivered as live lectures and discussions by Harpp.

- Second, the open edX platform featured a discussion board where students and alumni participated in weekly discussions. This venue was considered the heart of the course, in that it encouraged the most intense student-alumni interaction throughout the semester. Alumni participants were not required to have prior knowledge of the course material; nevertheless, Harpp hoped they would contribute perspectives on the course content, particularly historical perspectives, gleaned from their personal experiences.

- Third, videoconferences were arranged between small numbers of students and alumni.

- Fourth, students and alumni collaborated to construct a timeline of the Atomic Age using a web-based application.

- Finally, alumni could follow and participate in a Twitter project, in which campus-based students reenacted the events of the atomic bomb story playing the roles of major historical figures.

Second Online Experiment: Changes to the Course

In fall 2014, Colgate hosted a symposium about online education, inviting several pioneers in the field to share their experiences with the campus (see table 3). As a result of these discussions, five undergraduate students voluntarily joined Harpp in an extensive reworking of the 2014 online course for the 2015 semester, serving as full-fledged course designers and receiving course credit. The second version of the online Atomic Bomb course was offered in spring 2015 on edX Edge. This iteration of the course was designed to implement and test several innovations intended to enhance interactivity among participants and increase their engagement with the course material.5

Table 3. 2014 Online Education Symposium

|

Speaker |

Institution |

Talk |

|---|---|---|

|

Fiona Hollands |

Columbia University Teachers College |

|

|

George Siemens |

University of Texas in Arlington |

|

|

Marc Bousquet |

Emory University |

Video Lectures and Comprehension Questions

One major change to the 2014 version of the course involved the video lectures. A study that analyzed the dropout rate of online lecture videos in edX MOOCs found that videos longer than six minutes result in a significant decrease in learner engagement.6 Consequently, to encourage participants to watch the videos and to establish a positive learner experience, we edited the videos into multiple shorter units, ranging from three to 17 minutes in length.

We also placed questions about course content (see figure 1) between the newly segmented videos. Inspired by ConcepTests,7 we aimed to ensure viewers paid attention and reviewed important points in a participatory manner. Dr. Arthur Ellis, who created ConcepTests, concluded that brief assessments motivate students to engage more effectively with the material while receiving immediate feedback about their level of comprehension. This technique also allows students who might not learn best through auditory instruction to work through material in an alternative way.8

Figure 1. Example comprehension question

In 2015, on-campus students were required to watch the video lectures on edX prior to coming to class, instead of receiving the content live. By flipping the classroom,9 we created more time in class for hands-on activities, in-depth investigation of concepts, and discussions.10 In 2014, 18 of 27 class periods were predominantly lecture-based, whereas in 2015, that number was reduced to three. (The 2015 course schedule is available on the edX Edge site.)

Discussion Group Cohorts

MOOCs display a common phenomenon wherein less than 10 percent of students contribute roughly 90 percent of discussion posts.11 The low sustained participation rate on the discussion board may be attributed to three potential factors.12 In classes with many students (even a SPOC), there is a perception of pressure to say the "right" thing, with the fear of one's peers becoming argumentative.13 The second factor is social-loafing: in a group setting, the responsibility for maintaining the discussion is spread across all members, creating a passive attitude within the class or discussion forum.14 The third factor is the notion of getting lost. The probability that a student's post or comment will be left in the abyss of a forum consisting of several hundred or thousand participants is fairly high. If posting is not required in a given course, between 10 and 50 percent of initiated threads are "orphaned," receiving no response.15 If students do not actively engage with each other, the discussion forum loses its telos.

To address the low participation rate in discussion fora in the 2015 version of the course, we established cohorts of participants within the discussion board on the edX Edge platform. We applied the observation that small classes allow for greater levels of student participation in addition to heightened levels of responsibility to maintain conversations.16 We originally divided the class into 10 cohorts of two students and approximately 25 alumni (possible because 250 alumni signed up). The students and alumni were placed in each cohort based on their responses to a pre-course survey in which they assessed their prior knowledge of the course subject and indicated their political leanings. The intent was to enliven discussions by combining individuals with a variety of knowledge levels, life experiences, and political ideologies. Midway through the semester, we merged several cohorts to invigorate groups that had stagnated in terms of alumni participation.

Fireside Chats

In 2015, we also implemented a type of assignment we named "Fireside Chats" [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d38NWODYOQg]. These weekly videos, designed by two to five students, focused on a topic of their choice from recent course content. They posted the completed video online for all course participants to view. The intentions behind creating this assignment were three-fold.

- First, these videos permitted students to delve further into aspects of the course that were not discussed fully in class.

- Second, the videos gave alumni the opportunity to catch up on particularly interesting discussions from the previous week that might have occurred outside of their assigned cohorts.

- Third, we wanted the alumni to develop greater familiarity with the students in their discussion forum cohorts. The Fireside Chats provided a visual connection between online and in-class participants.

Wordpress Blog

In our recruitment of alumni participants, we explained that the course was modular, allowing them to tailor their participation according to their schedules and interest levels. Consequently, we anticipated that some alumni would only engage at the periphery of the course. Using the WordPress system, which we embedded into the edX platform, we created a blog [https://colgatexplus.colgate.edu/s15-core138/] to provide lightly engaged participants with a mechanism to keep up with the course. The blog included course highlights (notable conversations collected from across cohorts), resources (links to additional articles and websites of interest), Fireside Chat videos, select completed student assignments, and course documents such as exams and project assignment descriptions.

Miscellaneous Additions

Two additional amendments to the 2015 course were the Video Postcards and the Expert Lectures. Video Postcards [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLnyfgOut1c&list=PL5_mdEPDLIafsteq13lupDtVAsMF4l4yN&index=2] were short video messages that Colgate students sent from around campus and that alumni submitted from their various global locations. The postcards constituted another effort to connect faces to names and to enhance the connection between in-class and online participants. Expert Lectures were events during which invited speakers delivered content for the course either on campus or via videoconference; they were recorded and posted to the edX platform. Speakers included individuals from the Smithsonian, the Atomic Heritage Foundation, and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. These events shared details about specific aspects of the course that the video material did not otherwise cover, serving as examples of practical applications of course concepts. These events also provided opportunities for the students to interact directly with the experts and for the alumni to observe a class (albeit a previously recorded one). Finally, the Twitter historical play project was implemented a second time; the full transcript of 2015 posts by the students is available online [http://www.colgate.edu/alumni/colgatex/atomic] (scroll to bottom of the page and it will load progressively).

Preliminary Data and Analysis

During the 2015 course, we surveyed participants three times (pre-, mid-, and post-course). We collected usage data from the discussion forum on edX, along with anonymized midterm and final exam grades for the Colgate students. We used the data to assess the impact of the 2015 course amendments in terms of participant engagement in course activities and forging student-alumni connections.

Video Lectures and Comprehension Questions

In 2014, 78 percent (n = 40) of alumni self-reported that they watched the course videos; in 2015, alumni self-reported a completion rate of about 95 percent (n = 43). We theorize that more alumni watched the lectures owing to the videos' shorter length than in the 2014 course. The majority of 2015 videos were roughly 10 minutes long, a length that is sensitive to adults' typical peak learning period.17 We believe shortening the lectures effectively kept participants engaged and helped them learn the content. In 2015, alumni participants looked at video lectures more frequently than at the discussion forum, Fireside Chats, or WordPress.

The majority of alumni and students (73 percent [n = 41] and 80 percent [n = 15], respectively) chose to use the optional comprehension questions added in 2015. Most participants found these questions helpful, improving their understanding of course material (87 percent of alumni [n=30] and 83 percent of students [n = 12]). On average, students who completed the comprehension questions scored approximately eight points higher on the midterm and final exams than their peers who chose not to do the questions. Although we cannot prove causation, there is a positive relationship between those who answered the questions and higher exam scores (R2 = 0.32).18

Some participants thought the questions were overly simplistic — a not unfounded criticism. The formats available for automatically graded questions on the edX platform are limited, which poses a challenge to writing sophisticated, thought-provoking questions. To achieve a higher intellectual level for video-related comprehension questions, Harpp would have needed more teaching staff to help with grading and to provide appropriately detailed, content-based feedback.

Discussion Board

In the 2015 offering of the course, we established discussion board cohorts in an attempt to strengthen connections between students and alumni and to encourage more sustained contributions from the online participants. Despite the fact that the total number of alumni participants decreased from 380 in 2014 to 250 in 2015, the 2015 offering had higher alumni participation on the discussion boards, as reflected in two metrics:

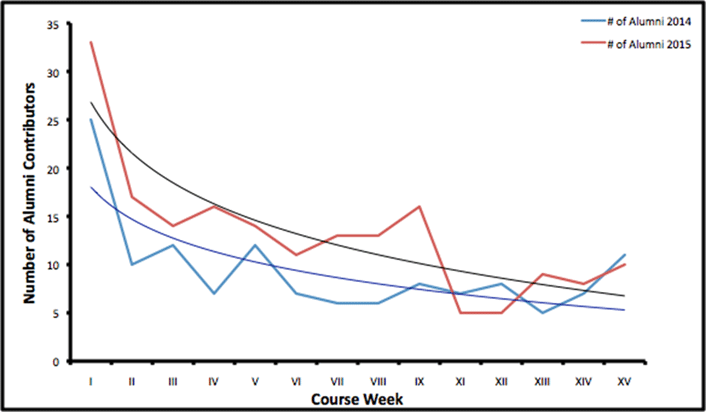

- The total number of alumni who post and comment in a given week (figure 2)

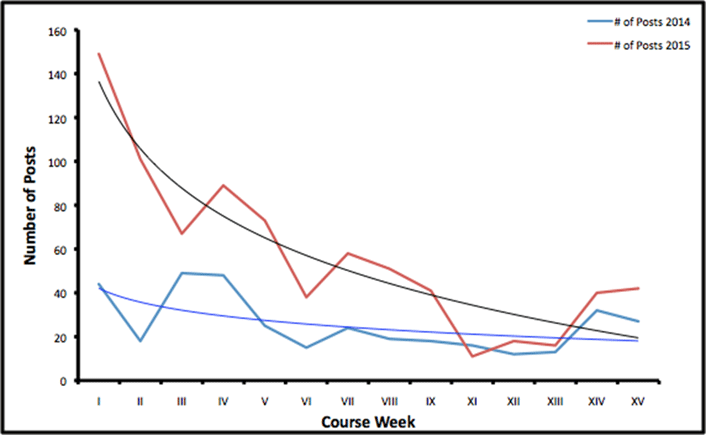

- The total number of alumni contributions to the discussion board per week (figure 3)

Figure 2. Total alumni posts and comments per week (week X omitted — no new discussion topic)

Figure 3. Total alumni posts per week (week X omitted — no new discussion topic)

For the duration of the course, both the total number of alumni contributors and contributions per week in 2015 exceeded those in 2014. This is true in an absolute and a relative sense, because the median number of alumni contributors per week in 2015 was 13, whereas in 2014 it was eight. The average proportion of enrolled alumni contributing to the discussion board each week in 2014 was two percent, whereas in 2015 it increased to five percent. The increase cannot be attributed unequivocally to the initiation of cohorts in the discussion board; the change might result from confounding variables such as repeat participants, differing recruitment strategies, or changes in discussion topics.

Both the number of alumni contributors and the number of posts in 2015 can be represented by logarithmic functions with high correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.73 and R2 = 0.84, respectively). In 2014, correlations were not as strong (R2 = 0.55 for alumni contributors and R2 = 0.30 for total posts). The importance of these values is that MOOCs also tend to have logarithmic decreases in discussion board participation rates.19 Similar to a pattern observed in MOOCs, 53 percent of all alumni posting in the 2015 course occurred in the first five weeks; in 2014, 49 percent of all alumni posting transpired during the same period. Thus, the larger number of active alumni in 2015 may have made our SPOC's discussion participation rates more like those of a MOOC. Further, this observation suggests the establishment of cohorts does not prevent poster attrition.20

Careful selection of the discussion topics might address the logarithmic attrition rates21 in discussion forum participation. During weeks in which discussion prompts were opinion-based, an average of 14 alumni actively contributed; in fact-based weeks, an average of 12 alumni actively contributed. Opinion-based discussion questions might encourage more participation, perhaps because participants do not feel they need as much preparation and previous knowledge (table 4).

Table 4. Sample discussion board prompts calling for fact- or opinion-based responses

|

Opinion-Based Prompts |

Fact-Based Prompts |

|---|---|

|

Would you, as a nuclear physicist in the early or mid-stage of your illustrious career, have joined in the project if asked? Why or why not, and what would have motivated your decision? What would you have needed to know about the project in order to be convinced to join? |

Did World War I introduce a new era of warfare? If so, what was the role of technology in that shift and its significance, ultimately, for future wars? |

|

As President Truman, what decision would you have made in August of 1945 about using atomic weapons in WWII? What factors would you have taken into account; which ones might have swayed your opinion in one way or the other? |

What factors contributed to the departure of Eastern European scientists from their homelands, and what may have motivated many of them to join the Allied war efforts? |

|

No nuclear weapons have been used in war since the 2 bombs were dropped in 1945 on Japan. Was the use of the atomic bombs in WWII the end of nuclear war or just the beginning, in your opinion? |

Let's explore the essential differences between the European and Pacific theaters during World War II. How did fighting styles differ, what was it like for soldiers operating in each region, and what strategic adjustments were necessary as a result of those differences? |

Even if the cohorts increased online participant engagement, they posed additional challenges to the 2015 course. Early in the semester, some discussion groups were less active than others due to the presence of "lurkers" — participants (alumni in our case) who read, but rarely contributed to, the discussion forum.22 To revive the "dead" cohorts, we decreased the number of discussion groups from 10 to five, thereby increasing the number of active contributors in each cohort. In Weeks IV and VII (see figure 2), we formed larger discussion groups and saw small spikes in the number of posts by alumni (students remained fairly consistent with their posting throughout because they were required to contribute weekly). Our experience suggests the need for a minimum number of active participants to establish critical mass for continuous, lively conversation. During the 2015 course, groups with fewer than seven active contributors could not sustain discussions. Large groups (over 50 active participants) had a higher number of interactions than medium (11–50 active participants) and small (0–10 active participants) ones; however, a higher proportion of the group consists of active participants in medium and small groups compared to larger ones.23 Although the number of interactions dropped with the creation of cohorts, the smaller groups fostered an environment wherein each individual participant felt encouraged to post more frequently than in a discussion without cohorts.

Fireside Chats

One goal of the Fireside Chats was to encourage the alumni to get to know the students. Although our survey data do not indicate a strong relationship between watching the videos and becoming familiar with the students, the Fireside Chats might have heightened the connections alumni felt to the university. According to our post-course survey in 2015, 79 percent (n = 43) of the alumni who watched the Fireside Chats enjoyed them, and 78 percent (n = 23) of the alumni who enjoyed the Fireside Chats also indicated a greater likelihood of interacting with Colgate (as an institution) as a result of the class.

Another intent behind the Fireside Chats was to provide students with an additional medium to interact with the material and hence develop confidence in their knowledge. Students who experientially interacted with the course material by creating Fireside Chats reported higher confidence in their understanding of the course content compared to alumni who could only watch the Fireside Chats (60 percent [n = 15] to 45 percent [n = 29]). Consistent with Werner Severin's "cue summation" principle of learning theory, the additional mode of interaction increased learning.24 In the case of the Fireside Chat videos, the surveys suggest that they offered a worthwhile pedagogical tool for the current Colgate students.

WordPress Blog

The WordPress Blog — a late addition to the 2015 course — aimed to provide alumni and students with an overview of the content in the discussion forum and in class. The WordPress Blog was the least viewed aspect of the course, however, with only 35 percent (n = 43) of alumni and 20 percent (n = 15) of the students self-reporting that they visited the blog. WordPress Blog users (60 percent [n = 15] of alumni and 67 percent [n = 3] of students) stated that the content on the blog made the class more interesting; 67 percent of both students (n = 3) and alumni (n = 15) reported that the content of the blog helped solidify their understanding of course content.

For those who visited the blog, it accomplished its goal of helping participants develop a stronger understanding of the course content. Unfortunately, few participants used the WordPress Blog to its capacity as an additional resource, most likely due to lack of advertisement and its delayed introduction. Additionally, a plethora of course components were updated weekly, so participants might have prioritized other aspects over the WordPress Blog. The blog also posed a challenge from the course support perspective, in that its maintenance required significant, ongoing attention from staff throughout the semester. This resulted in a lag in posting relevant material, which in turn might have contributed to the lack of use by participants.

Additional Observations

Several minor, but important, effects of our amendments to the online course warrant mention. First, the data revealed a precipitous drop in discussion board contributions during the three weeks following spring break (see figures 1 and 2). The decreased activity level might result from the timing of the break: The same discussion topic remained active during Weeks IX and X, no new video lectures were posted, and reduced student activity appeared online. With fewer active participants, the number of potential interactions might have fallen below a critical level at which substantial conversations could occur.25 Moreover, the break might have disrupted alumni routines, leading to the lowest participation rates of the course — from which they never quite recovered.

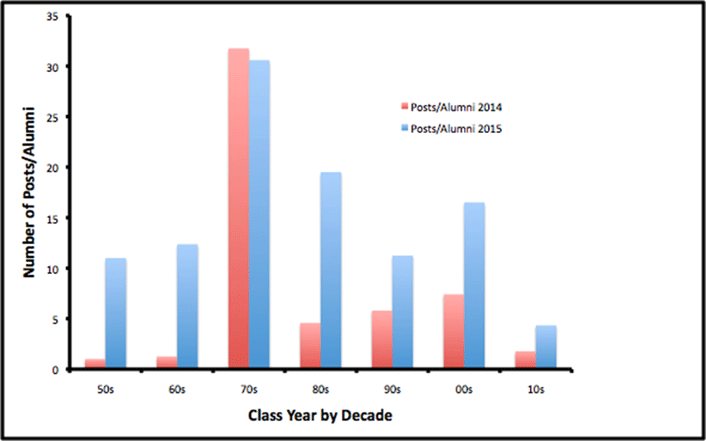

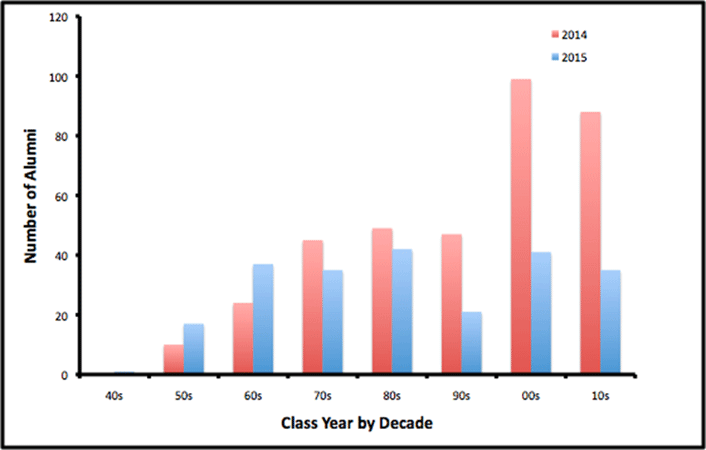

Generally speaking, the more active alumni on the discussion board came from classes that graduated in the 1970s and 1980s; we observed this phenomenon in both iterations of the course, although it was far more apparent in the 2015 version (figure 4). We deemed a number of these active alumni "superposters."26 In our case, we define superposters as individuals who posted 15 or more times. In 2014, six individuals (two percent of the class) produced 71 percent of all alumni contributions. In 2015, 13 individuals (five percent of the class) accounted for 84 percent of all alumni activity. Our results are consistent with the observation that in MOOCs, less than 10 percent of the students make 90 percent of all posts.27 From our experience in 2014, fewer members of the more recent graduating classes (2000s–2010s) seemed interested in engaging with current Colgate students.

Figure 4. Average posts per active alumnus by graduation class decade in 2014 (red) and 2015 (blue) courses

In 2015 we recruited alumni participants through social media, as in 2014, but also used physical mailings to more senior alumni with a goal of increasing enrollment rates of individuals who might not have seen social media–based methods. An influx of alumni from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, a slight decrease of participants from the 1970s and 1980s, and a dramatic decrease in enrolled alumni from the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s occurred between the 2014 and 2015 courses (see figure 5). Based on our experience, social media advertising effectively recruits young alumni, whereas physical mailings more effectively reach senior participants.

Figure 5. Alumni participants by graduation class decade in the 2014 (red) and 2015 (blue) courses

The undergraduate students had a mandatory posting requirement each week, and their performance on the discussion board affected their final course grade. An earlier study conducted by Cho Kin Cheng, Dwayne E. Paré, Lisa-Marie Collimore, and Steve Joordens showed that stronger voluntary participation in the discussion forum led to higher grades on exams.28 In our course, students who posted more than the required amount on average scored higher on exams than those who posted below the required amount.

Finally, in our post-course survey in 2015, only 49 percent (n = 43) of alumni reported an improvement in their understanding of ethical content, whereas 87 percent (n = 15) of the students indicated a positive change. This discrepancy might be attributed to the mode of content delivery. Of the undergraduate students, only six percent said online video lectures were a more effective medium for learning ethical material than in-class delivery. Scientific content, in contrast, was more successfully delivered via the online video lectures; both alumni and students expressed similar levels of confidence with their improvement in this area (84 percent [n = 43]; 87 percent [n = 15]). When asked to compare their learning of scientific material in the video lectures compared to in-class lectures, 63 percent (n = 10) of students indicated video lectures as equal to or more effective than in-class delivery. We conclude that the online platform enhanced the effectiveness of learning factual and scientific concepts. In certain content areas, however, such as the subtleties related to ethical questions, it could not replace classroom interactions.

Recommendations

Our experience has provided insight into the process of implementing online courses at an undergraduate liberal arts college in several key ways. We found that at a small university, the human capital required to produce a worthwhile online educational experience requires significant, sustained institutional support. Even with a team of six student course developers and one instructor, we struggled to keep some of the components of the course current (i.e., the WordPress Blog), and, throughout the course, we usually found ourselves rushing to meet deadlines.

Considering the number of participant activities in the course, we recommend creating a list that participants can visit to see the interaction options. Many alumni and students often found themselves at a loss as to how to manage all of the options provided for them in a systematic way.

Also, consider redesigning the platform to be accessible for participants with all levels of technological literacy. Throughout the semester, we fielded questions from alumni (particularly more senior individuals) who struggled with navigation of the platform; the edX discussion board was the most frequently criticized for its confusing layout. One possible solution is to create instructional videos or documents that provide participants with an overview of how to navigate the course platform. We did this to some extent, but found that our help documents at times did not suffice for the less technology-savvy online participants.

In recruiting alumni participants, tailor communication methods to the needs and abilities of the different demographics. Younger alumni can be reached easily using conventional social media (Facebook, Twitter), but more senior individuals who less frequently use such technology are more successfully recruited using traditional methods such as postcard mailings.

Conclusions

The Advent of the Atomic Bomb adapted online education technology to the liberal arts classroom to enhance the current students' classroom experience, to engage alumni in the intellectual process, and to forge connections between students and alumni. Not surprisingly, many of our recommendations reflect current best practices in online education.29 Some of our specific findings include:

- Videos of three to 17 minutes appeared to help maintain participant engagement.

- A higher number of students and alumni found the comprehension questions helpful after viewing the videos. We do need to determine better ways to create effective, in-depth comprehension questions, however.

- Cohorts had a positive impact on alumni discussion board participation rates. Small cohorts might encourage participants to engage in a sustained way with the course and with students within their groups, thus reducing the number of lurkers. However, groups must be large enough to maintain continuous, lively discussions, yet small enough to encourage participants to build strong relationships.

- Having a larger number of more senior participants led to an increased number of superposters.

- Discussion topics that tie in personal experiences or opinions, rather than just factual content, tended to enhance online participation rates.

- Fireside Chats provided an effective pedagogical tool for the students and could foster more substantial connections between alumni and their alma maters. However, they are time-consuming to prepare, making them a costly addition to the course in terms of support staff. For the Fireside Chats to be useful as an educational mechanism for online participants, we suggest that they produce their own videos, which poses additional technical and logistical challenges.

- The WordPress Blog had the capacity to supplement student and alumni learning; however, we found it difficult to manage with the resources available. Making it more accessible and publicizing it better to the participants might have increased its use.

Our experiment with The Advent of the Atomic Bomb demonstrates the possibility of integrating the ideals and values of a liberal arts classroom into an online platform, which enhanced the students' in-class experience specifically. Furthermore, alumni and students forged strong relationships as a result of their protracted interactions throughout the semester. Finally, alumni had the opportunity to reconnect with their alma mater in an educational setting. Colgate University's foray into hybrid online education illustrates the considerable potential for liberal arts colleges to benefit from the judicious adaptation of online educational technology.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ishir Dutta, Mark Hilton, Taylor Mooney, and Zachary Weaver for their contributions as undergraduate course designers on the 2015 atomic bomb class. We are also grateful to Peter Tschirhart, assistant dean for Undergraduate Scholars Programs at Colgate University, for helpful conversations and coordination of the online education symposium in the fall of 2014. Kevin Lynch, chief information officer at Colgate University, and Ahmad Khazaee, assistant director for End User Support, provided intellectual and logistical support for the project.

Author Allison Zengilowski was supported by the Natural Sciences Division at Colgate University's Summer Research Program; Sidhant Wadhera was supported by a grant from Information Technology Services.

David N. Harpp (McGill University), Brandon Bray (Environmental Protection Agency), and Arthur J. Steneri (Colgate Class of 1956), as well as several anonymous journal reviewers, provided helpful suggestions to improve the manuscript.

Finally we would like to thank the students and alumni who participated in the 2015 iteration of The Advent of the Atomic Bomb.

Notes

- Laura Pappano, "The Year of the MOOC," New York Times, November 2, 2012.

- Alexander McAuley, Bonnie Stewart, George Siemens, and Dave Cormier, "The MOOC model for digital practice," (2010), 1–63.

- Fiona Hollands and Devayani Tirthali, "Resource Requirements and Costs of Developing and Delivering MOOCs," International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, Vol. 15, No. 5 (2014): 113–133.

- Sean Coughlan, "Harvard plans to boldly go with 'Spocs'" BBC, September 24, 2013.

- Kathleen Burnett, Laurie J. Bonnici, Shawne D. Miksa, and Joonmin Kim, "Frequency, Intensity and Topicality in Online Learning: An Exploration of the Interaction Dimensions that Contribute to Student Satisfaction in Online Learning," Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, Vol. 48, No. 1 (2007): 21–35.

- Juho Kim, Philip J. Guo, Daniel T. Seaton, Piotr Mitros, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, and Robert C. Miller, "Understanding In-Video Dropouts and Interaction Peaks in Online Lecture Videos," Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@scale, ACM (March 2014), 31–40.

- David A. McConnell, David N. Steer, Katharine D. Owens, Jeffrey R. Knott, Stephen Van Horn, Walter Borowski, Jeffrey Dick, Annabelle Foos, Michelle Malone, Heidi McGrew, Lisa Greer, and Peter J. Heaney, "Using ConcepTests to Assess and Improve Student Understanding in Introductory Geoscience Courses," Journal of Geoscience Education, Vol. 54, No. 1 (January 2006): 61–68; and Todd Wimpfheimer, "Chemistry ConcepTests: Considerations for Small Class Size, Journal of Chemical Education, Vol. 79, No.5 (May 2002): 592.

- McConnell et. al, "Using ConcepTests to Assess and Improve Student Understanding."

- Bill Tucker, "The Flipped Classroom," Education Next, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2012): 82–83; and Kathleen Fulton, "Upside Down and Inside Out: Flip Your Classroom to Improve Student Learning," Learning & Leading with Technology, Vol. 39, No. 8 (June/July 2012): 12–17.

- Tucker, "The Flipped Classroom."

- Bharat Anand, Jan Hammond, and V.G. Narayanan, "What Harvard Business School Has Learned About Online Collaboration," Inside Higher Ed, April 16, 2015.

- Jeremy D. Finn, Gina M. Pannozzo, and Charles M. Achilles, "The 'Why's' of Class Size: Student Behavior in Small Classes," Review of Educational Research, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Fall 2003): 321–368; and Robert R. Weaver and Jiang Qi, "Classroom Organization and Participation: College Students' Perceptions," The Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 76, No. 5 (September/October 2005): 570–601.

- Weaver and Qi, "Classroom Organization and Participation."

- David A. Sears and James Michael Reagin, "Individual Versus Collaborative Problem Solving: Divergent Outcomes Depending on Task Complexity," Instructional Science, Vol. 41, No. 6 (November 2013): 1153–1172.

- Jonathan Huang, Anirban Dasgupta, Arpita Ghosh, Jane Manning, and Marc Sanders, "Superposter behavior in MOOC forums," Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@scale conference, ACM (March 2014), 117-126.

- Weaver and Qi, "Classroom Organization and Participation."

- Kim et. al, "Understanding In-Video Dropouts and Interaction Peaks"; and Charles Prober and Sal Khan, "Medical Education Reimagined: A Call to Action," Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Vol. 88, No. 10, (2013): 1407–1410.

- Christopher R. Poirier and Robert S. Feldman, "Promoting Active Learning Using Individual Response Technology in Large Introductory Psychology Classes," Teaching Psychology, Vol. 34, No. 3 (2007): 194–196.

- Lori Breslow, David E. Pritchard, Jennifer DeBoer, Glenda S. Stump, Andrew D. Ho, and Daniel T. Seaton, "Studying Learning in the Worldwide Classroom: Research into EdX's First MOOC," Research & Practice in Assessment, Vol. 8 (Summer 2013): 13–25.

- Andrew D. Ho, Isaac Chuang, Justin Reich, Cody Austun Coleman, Jacob Whitehill, Curtis G. Northcutt, Joseph J. Williams, John D. Hansen, Glenn Lopez, and Rebecca Peterson, "Harvard and MITx: Two Years of Open Online Courses, Fall 2012-Summer 2014," March 30, 2015, posted on Social Science Research Network.

- Daphne Koller, Andrew Ng, Chuong Do, and Zhenghao Chen, "Retention and Intention in Massive Open Online Courses: In Depth," EDUCAUSE Review, June 3, 2013.

- Blair Nonnecke and Jenny Preece, "Silent Participants: Getting to know Lurkers Better," in From Usenet to CoWebs: Interacting with Social Information Spaces, Christopher Lueg and Danyel Fisher, eds. (Springer: 2003): 110–132.

- Avner Caspi, Paul Gorsky, and Eran Chajut, "The Influence of Group Size on Nonmandatory Asynchronous Instructional Discussion Groups," The Internet and Higher Education, Vol. 6, No. 3 (2003): 227–240.

- Werner Severin, "Another Look at Cue Summation," AV Communication Review, Vol. 15, No. 3 (September 1967): 233–245.

- Caspi, Gorsky, and Chajut, "The Influence of Group Size."

- Huang et. al, "Superposter Behavior in MOOC Forums."

- Anand, Hammond, and Narayanan, "What Harvard Business School Has Learned About Online Collaboration."

- Cho Kin Cheng, Dwayne E. Paré, Lisa-Marie Collimore, and Steve Joordens, "Assessing the Effectiveness of a Voluntary Online Discussion Forum on Improving Students' Course Peformance," Computers & Education, Vol. 56, No. 1 (January 2011): 253–261.

- Jared Keengwe and Terry T. Kidd, "Towards Best Practices in Online Learning and Teaching in Higher Education," Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June 2010).

Allison Zengilowski is a member of the Benton Scholars Program at Colgate University. She is an undergraduate student in her third year at Colgate studying Psychology and Peace and Conflict Studies. After serving as a developer for a SPOC offered on edX, she and her co-researcher, Sidhant Wadhera, presented their findings on adapting MOOC technologies to the liberal arts classroom at the Learning with MOOCS II [http://www.learningwithmoocs.org/] Conference at Columbia University in October, 2015. She hopes to further pursue research on and advancement of online education by investigating the cognitive aspects of being an active participant or lurker in an online course.

Sidhant Wadhera is a member of the Benton Scholars Program at Colgate University. He is in his third year at Colgate obtaining his bachelor's in Mathematical Economics and Political Science. After serving as a developer for a SPOC offered on edX Edge, he and his co-researcher, Allison Zengilowski, attended the Learning With MOOCs II Conference at Columbia University in October, 2015. At the conference, they discussed their research on adapting MOOC technologies to the liberal arts classroom. This semester he is investigating the impact of online courses on alumni donation patterns.

Karen Harpp is a professor in the Geology Department and the Peace and Conflict Studies Program at Colgate University. She taught Colgate's first online course, The Advent of the Atomic Bomb, which integrated on-campus students with alumni, and is currently offering a class in which students design online educational materials for children. Online resources related to these efforts include: (a) A presentation about the bomb course given at a Disruption Symposium in 2014; (b) a Chronicle of Higher Education article on the course; and (c) a description of the online Twitter project.

© 2015 Allison Zengilowski, Sidhant Wadhera, and Karen Harpp. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International.