Presenting evidence of learning should be a hallmark of society's increasing orientation toward lifelong learning and transparency of capabilities. Executing this vision requires a far-ranging systemic effort.

Sarah hurries from her car, trying to avoid being late for the 6:30 p.m. meeting with Max, her academic advisor. She never feels they have enough time to review her goals for completing her degree, since Max teaches class most nights. Sarah is a project coordinator at Maple Pharmaceuticals, and she hopes that a bachelor's in business operations will improve her prospects for a promotion and a transfer into the supply and logistics department. Lately, however, Sarah has feared that her business operations courses are not well aligned with the work she wants to do or with the expectations of her employer, who is subsidizing her program. The workplace-oriented assignments in her classes seem too basic compared with the complexity of the issues she faces on a regular basis.

Moreover, Maple's growth is slowing, and Sarah has heard rumors that there may be a hiring freeze. She has not looked for a job in more than seven years, and she feels ill-equipped to conduct a job search outside Maple. The college's career services office is under-resourced—it's open only during the day, when Sarah is at work—and the online career-planning resources she has access to do not offer good data on the local employment landscape. Max has not been very helpful on this front either. Sarah is developing a profile on LinkedIn at the suggestion of her brother-in-law, but her first effort is sparse compared with most of the other profiles she has scanned. A friend has recommended she hire a job coach, but Sarah doesn't think she can find one, let alone afford one…

Imagine a more integrated, student-centric environment for Sarah. One in which institutional resources are more tightly aligned with her goals. One in which academic programs are infused with rigorous and relevant workforce considerations and competency development. One in which institutions help post-traditional students like Sarah capitalize on technology tools to highlight their academic and professional capabilities. One in which institutions fully embrace the student learning that occurs outside the classroom, creating more efficient and cost-effective pathways for students. One in which Sarah's experience looks more like this:

Sarah is meeting her program mentor, Max, at 6:30 p.m. on campus to review the remaining set of competencies she needs to earn her bachelor's degree in business operations and to get additional feedback on her work portfolio presentation last week. These work experiences at Maple Pharmaceuticals covered nearly 40 percent of the competencies required for her degree, but her prior learning assessment reveals that she needs a bit more work in some areas. The college's academic advisory team had paired her with Max within a few days of her enrollment, based on her program goals and his operations experience in industrial manufacturing, and it's been a great match.

After six months in the program, Sarah is thrilled at how fully the college values her professional experiences, aligning them with her academic objectives while still challenging her to demonstrate her capabilities in new and different contexts. The college has let her set the pace of her progress, and she feels as though she is sprinting toward her degree. Tonight, Sarah wants to focus with Max on a new opportunity she has at work to head up a process-improvement initiative; she believes it fits with several of her outstanding team leadership and communication objectives, as well as potentially with some in managerial economics. Moreover, Sarah has already persuaded Jeffrey, the process-improvement director at Maple, to draft a memo evaluating her performance upon completion of the initiative for inclusion in her portfolio.

Max has also helped Sarah understand the value of the right social networks for professional networking and development. He has provided coaching and feedback on her initial efforts to develop an online profile, and he even directly connected her with several of his former colleagues on one of the networks. As Sarah enters the student center to meet with Max, she could not have imagined that returning to school to complete her degree ten years after leaving college would be such a comprehensive, service-oriented experience…

A shift in expectations is occurring among core postsecondary education stakeholders—students, employers, and institutional administrators and faculty—regarding the evidence of learning that is required in today's world and its effective validation and presentation. At Tyton Partners, we define evidence of learning as "the body of knowledge, skills, and experience achieved through both formal and informal activities, that individuals accumulate and validate during their lifetime." The ability of individuals to present their evidence of learning should be a hallmark of our society's increasing orientation toward lifelong learning and transparency of capabilities. In practice, executing this vision requires a far-ranging systemic effort within higher education institutions and across stakeholder communities.

The Current State of Evidence

Many colleges and universities are under siege today. From record-high student debt loads induced by escalating tuition costs and diminishing state subsidies to proliferating technologies and delivery models seeking to undermine the historical value of the college/university education, to employers' laments over the caliber and quality of graduates' knowledge and skill base, hardly a day passes without some commentary impugning the value and relevance of the U.S. higher education system. Moreover, as policy conversations shift from expanding access to postsecondary education to delivering and validating student outcomes, colleges and universities find an increasing level of scrutiny applied to their ability to capture and report performance outcomes.

At a macro level, the lifetime value of postsecondary education remains a strong incentive for individuals to invest time and financial resources in pursuing a terminal credential. The specific credential earned and the institution's brand serve as the key signals relative to student-accumulated learning and job alignment. However, at both the student and the employer levels, this thesis is proving challenging. Employers question the quality and relevance of institutional programs, and their confidence in what students actually know upon graduation is undermined. Transcripts—higher education institutions' official record for what a student has "learned"—are woefully light on details regarding nonacademic skills and experiences. Both the efficacy and the impact of the traditional transcript are waning as it fails to keep pace with the needs and expectations of students and employers; a transcript is a necessary but insufficient mechanism for representing one's background and expertise. For students, the transcript represents a time-delimited snapshot of their formal education, generally lacking a more holistic capture of supplemental learning achievements and noncognitive attributes. For employers, the transcript verifies that the candidate attended a postsecondary institution, but it does not necessarily convey how much the candidate actually learned along the way.

As experimentation with competency- and assessment-based learning models grows, the traditional transcript is increasingly being seen as inadequate and archaic. Foundational, lifelong skills such as critical thinking, teamwork and collaboration, and problem solving are climbing to the top of employers' wish lists, and yet few institutional measures capture these attributes. These dynamics are pushing students and employers to explore alternative platforms for both presenting and evaluating profiles that capture an individual's evidence of learning.

Building an Integrated "Evidence of Learning" Ecosystem

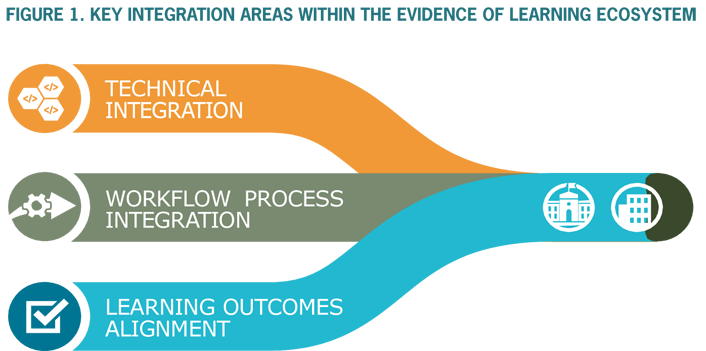

In response to these misalignments, numerous organizations and initiatives have emerged to help individuals, institutions, and employers more effectively capture, present, and evaluate what students have learned—their evidence of learning. This ecosystem of suppliers aims to augment and supplant historical tools and resources such as transcripts and resumes. The leading solutions reflect a more holistic, dynamic, and persistent view of an individual's educational background and experiences. Many of these initiatives, however, are not integrated with current institutional and employer processes and services, limiting their potential. This lack of integration exists in three critical areas:

- Learning Outcomes Alignment refers to a transparent, validated, and broadly accepted set of learning objectives—or competencies—tied to the attainment of terminal credentials. Currently, the existence of common learning objectives for academic programs across different colleges and universities remains elusive and is a source of inefficiency for students who are striving to maximize credits earned at multiple institutions. The Degree Qualifications Profile and the LEAP and VALUE initiatives from the Association of American Colleges & Universities are striving to move institutions in this direction. Further, many industry associations have developed competency maps and are seeking out educational partners to assist with implementation. Ultimately, integration in this area should bridge academic and applied education and skills expectations across institutions and employers to accelerate opportunities for students.

- Technical Integration remains a challenge for newer solutions seeking to connect with existing institutional systems and technologies. These issues extend beyond the institutional context and are reflected in the limited extent to which employers' human resources and recruitment systems integrate with those in use at colleges and universities. This dynamic inhibits the ability of students, institutions, and employers to efficiently share and access an individual's evidence of learning.

- Workflow Process Integration is another hurdle for many providers of evidence of learning solutions. For example, the workflow related to documenting and archiving student work is generally disconnected from an employer/recruiter's ability to view that work as evidence of an individual's skills and capabilities. Portfolio platforms remain an underutilized tool among students, institutions, and employers in this area. Vibrant badging and microcredentialing activity is occurring within supplemental learning environments and selected industries but remains generally disconnected from traditional institutional academic programs and assessment models.

For colleges and universities, evidence of learning is not a new concept. However, adopting and implementing strategies and practices to affect integration across services, technologies, workflow processes, and learning outcomes is necessary to strengthen higher education's support of and value to students and the workforce community. Postsecondary institutions are already uniquely positioned to drive this integration, given their existing organizational infrastructure and student support services. Unfortunately, at many institutions, these capabilities are not connected in a coherent manner for the benefit of students.

Colleges and universities have historically bridged the student and employer communities, developing and preparing individuals for a lifetime of productive contributions in the workforce and broader society. But a student's exposure to education through only one institution and only one academic program is no longer the norm and does not suffice in today's economy. Students have many more alternatives for closing knowledge and experience gaps, and employers also actively pursue programs to meet the needs of their workforce.

In response to these dynamics, colleges and universities need fresh thinking, commitment across the institution, and engagement with a broader set of stakeholders beyond the institution to more effectively capitalize on their resources to benefit students and employers. The core postsecondary community—administrators, faculty, professionals, and staff—has an opportunity to reimagine the higher education institution's integrative role and value vis-a-vis students and the workforce within an evidence of learning ecosystem.

Understanding the "Evidence of Learning" Framework

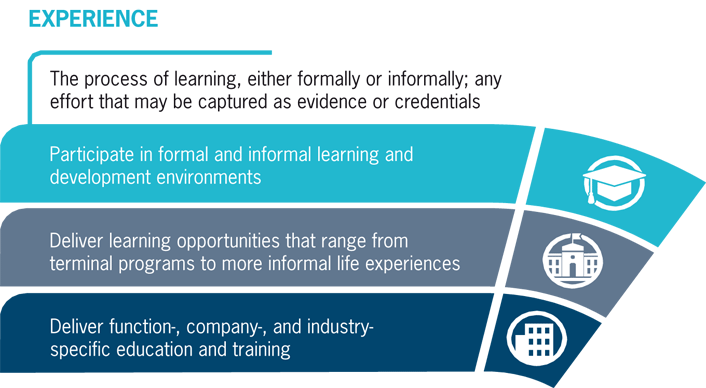

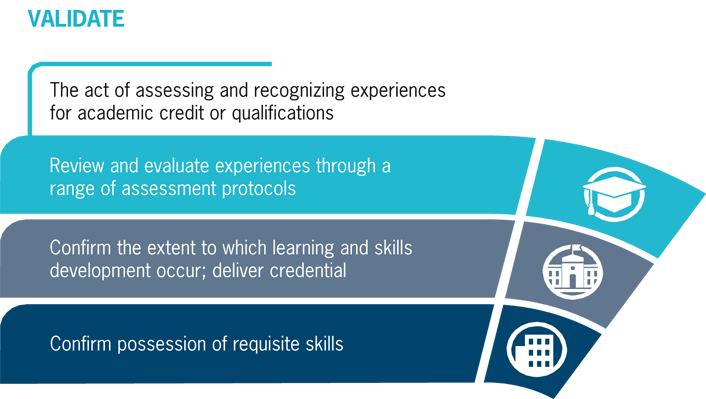

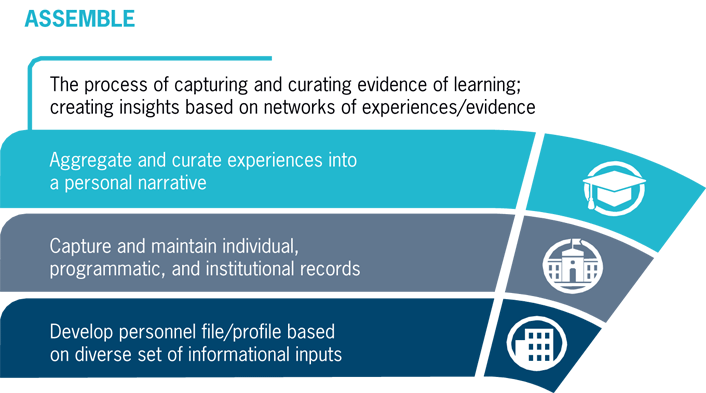

Imagine the potential benefits of an integrated framework that could lessen the friction across an individual's lifetime of learning and gainful employment. The Evidence of Learning Framework (EofL Framework) offers a guide. The EofL Framework highlights the key objectives and needs of its primary stakeholders: students, institutions, and employers. The framework is composed of five segments—Experience, Validate, Assemble, Promote, and Align—that form an iterative set of activities for each stakeholder group.

Integration within the EofL Framework should occur along the stakeholder-specific activities (the circular path for each stakeholder community), as well as within each segment's activities for the three stakeholder groups. The outcome is a more transparent, aligned set of expectations and behaviors enabling students' pursuit of college and career goals. Numerous examples of alignment exist between student and institutional stakeholders, between student and employer stakeholders, and between institutional and employer stakeholders; however, strong integration among all three communities remains elusive both within each segment (e.g., the Validate segment) and across the entire EofL Framework. This lack of alignment contributes to both the public angst regarding the efficacy and value of postsecondary education and the mushrooming investments in consumer- and employer-focused education delivery models and systems for capturing and measuring learner competencies.

Each segment of the EofL Framework is evolving as innovative software companies and technology-enabled education models proliferate. These changes are creating new opportunities for the core stakeholders while simultaneously challenging not only the relationships between students, institutions, and employers but also the existing infrastructure of the postsecondary education system.

The introduction of innovative online learning models began within the Experience segment, transforming the perception of where and how teaching and learning could occur. The meteoric rise of MOOCs and their variants, the promise of adaptive learning, and widespread social learning models represent some of the innovations within this segment. The rate of innovation in the Experience segment, as measured by stakeholder acceptance and experimentation, likely outpaces the progress in any other segment, highlighting one gap that exists within each stakeholder community's engagement with the EofL Framework. Notwithstanding the general mainstreaming of online education, there remains a degree of variability in the views of students, institutions and faculty, and employers regarding the effectiveness and credibility of online learning; thus, gaps and misalignment exist within the Experience segment across the stakeholder groups as well.

The activities in this segment represent a particular point of frustration for many students vis-a-vis institutions and employers, as students strive to secure credit and recognition for workforce learning and community experiences. Historically viewed as extracurricular—and unrelated to course-based learning—these activities can be as rich and transformative as any occurring in a more traditional academic environment, yet tremendous variability exists in organizations' willingness to acknowledge and validate these supplemental learning experiences. At the core of the EofL Framework is a systemic acceptance of validated student learning and development (i.e., Experience) without prejudice for its source, modality, or duration.

The Experience segment also represents an area of keen interest for investors, who dedicated nearly $1.5 billion in venture- and growth-stage financing to education-related businesses from 2012 through the first half of 2015.1 Much of this activity was directed at nondegree, nonaccredited education programs and activities that seek to disaggregate the value of a traditional credential. Companies and other educational providers (e.g., the military) in this area target students directly and deliver skills-based and industry-aligned programs emphasizing employability pathways that are not available at colleges and universities and/or are provided at a fraction of the cost of colleges and universities. Higher education institutions infrequently and inconsistently accept credit from these programs. However, a small but growing number of employers are partnering with these new learning providers to access "graduating" participants, acknowledging the value of their programs from a talent development and recruitment perspective.

This segment may represent the most challenging one in terms of integration of expectations and execution across the core stakeholder communities. Colleges and universities bestow credentials on individuals, signaling a knowledge and skill-attainment level that facilitates employers' hiring efforts and an individual's learning and professional trajectory. One of the primary goals of postsecondary accreditors is to confirm the academic quality and rigor of an institution's programs; accreditation provides a form of insurance for students, employers, and others seeking to evaluate an institution's "value." And yet, the brand promise of institutional credentials—and, more narrowly, coursework—faces challenges from both employers and students.

Recent research illustrates the considerable perception gap between the preparedness of college graduates and the expectations of employers. Only one-third of business leaders "agree" or "strongly agree" that postsecondary institutions are delivering graduates with the skills and competencies needed for their business. In addition, business leaders highly value employee candidates' knowledge in the field (84%) and their applied skills (79%) but not their postsecondary major (28%) or where they received their degree (9%).2 These impressions from the workforce community highlight a gap that colleges and universities must rally to address.

From a student's perspective, the proliferation of organizations offering nondegree, nonaccredited programs, as noted above, represents a market disruption in the postsecondary landscape. Although the academic credential will persevere, students are being presented with a dizzying array of alternatives seeking to develop and endorse individuals' capabilities and preparedness for workforce requirements.

One specific critique is that colleges and universities are not doing enough to evaluate and record the supplemental learning experiences and noncognitive attributes of individual students. Badging and other microcredentialing models aim to bridge the goals of students and employers, positing—in most cases—an alternative methodology for recognizing knowledge and insight in specific areas. This trend is related to institutions' ongoing efforts to streamline and enhance their transfer-articulation and degree-audit processes to improve value, transparency, and decision making for students. Moreover, given the continued growth of adult learners across the postsecondary spectrum, the ability of colleges and universities to validate and extend credit for students' prior education and training experiences is critical. For some institutions, it is—and will be—a differentiator and a source of competitive advantage.

These selected dynamics reflect pressure on the existing system and models for validating individuals' learning and experience. With the culture of assessment in the postsecondary ecosystem increasing in importance, colleges and universities face the challenge of proving their value to students and to employers, among other stakeholders.

This segment represents students' efforts to accumulate and package the breadth and depth of their learning. Key inputs and resources may include a resume, transcript(s), assessments, learning experiences outside of college, and expert recommendations. These individual resources seem rather anachronistic in a world where LinkedIn reports hosting more than 380 million individual profiles, where more than 75 percent of employers use social networks like LinkedIn for employee recruitment, and where industry- and function-specific online communities increasingly foster strong alignment among individuals and employers.3 Even though e-portfolios have experienced reasonable adoption in the postsecondary environment, with slightly more than 50 percent of institutions providing students with an e-portfolio service tied to the institution in 2013, their consistent, robust use across all aspects of a student's institutional experience remains an aspiration.4 Moreover, many of the legacy institutional portfolio platforms fail to delight students accustomed to consumer-oriented technologies and lack connections to employers and professional communities.

Exacerbating the unfulfilled promise of portfolio solutions in the Assemble segment is many students' lack of familiarity and/or experience with developing a dynamic personal profile or a portfolio that reflects their accumulated experiences. Helping students learn how to build and curate a personal and professional narrative would seem closely aligned with the mission of colleges and universities; addressing this gap—for example, through student orientation and first-semester or first-year programs—provides an opportunity for institutions striving to integrate elements of this segment more effectively.

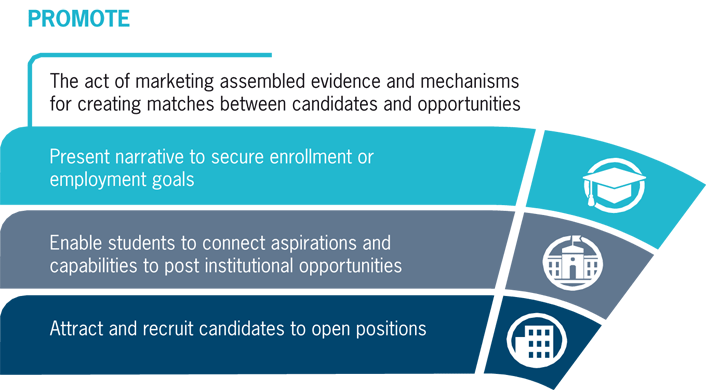

The Promote segment facilitates students' efforts to make the evidence of learning that they have assembled transparent and discoverable to priority stakeholders. College and university career services departments, historically key vehicles for supporting students in this personal marketing arena, are often under-resourced and ill-equipped to support the student population and the diversity of interest areas. The average ratio of students to career services professionals at postsecondary institutions is nearly 1,900 to 1; this figure rises to more than 5,000 to 1 at two- year institutions.5 In the absence of dedicated support resources or a clear professional pathway, students may struggle to effectively market themselves and their portfolio of skills and experiences.

In response, students are increasingly turning to noninstitutional career-development resources and networks to highlight their interests and pursue relationships that can enable their transitions to and within the workforce. LinkedIn, Monster, and CareerBuilder, among others, support millions of student profiles and have developed programs that specifically target high school and college students. Some industries and departments are turning to a new breed of businesses that uncover prospective employees through a blend of behavioral assessment, social media analytics, and other data-mining techniques. In both instances, the role of postsecondary institutions in this evolving alignment of supply (i.e., students) and demand (i.e., employers) is tenuous.

Most students today still need assistance with learning how to craft an effective narrative for workforce audiences and with understanding how best to leverage the web-based tools and channels available to them beyond the institution. Colleges and universities are uniquely positioned to aid students at this key juncture in the EofL Framework: higher education institutions possess infrastructure (i.e., advising and career services), alumni networks, and other resources to support and enhance students' ability to promote themselves. Marrying the technologies and tools with the advisory and mentoring services directed at the needs of students highlights the unique and differentiated value proposition that colleges and universities can offer.

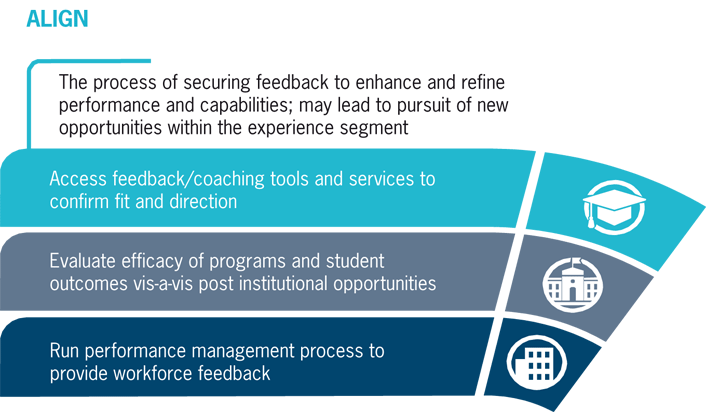

Within the EofL Framework, students, institutions, and employers aspire to consistently evaluate performance and fit to identify opportunities for improvement at both the individual (micro) and the enterprise (macro) levels. These feedback loops should be mutually reinforcing and a source of continuous improvement; the counseling and mentorship that students receive at their institution should enhance their performance and goal achievement while concurrently meeting institutional objectives and workforce-development considerations.

In reality, the Align segment includes an array of tools and services, from student-centric coaching to institution-centric program and enterprise accreditation review and process workflow solutions. In addition, employers adopt a distinct set of talent/performance solutions to manage their workforce and business requirements, with profitability and the satisfaction of stakeholders (e.g., customers, employees, partners) generally being the key outcome measures. This diversity creates information and data silos that make integrating stakeholder feedback and outcomes problematic; one need only consider the difficulty of tracking the path of students from their institutional to their workforce experiences to recognize how ill-equipped the U.S. postsecondary and workforce systems are to share insights on students. The result is an underwhelming return on investment—personally, professionally, and financially—for students, institutions, and employers.

A Call to Action

As highlighted above, the challenge of integrating the EofL Framework is most pronounced across the stakeholder communities, rather than within any one stakeholder group. This ineffectual alignment perpetuates a system in which the feedback or input from one group (e.g., institutions) to another (e.g., students) may not be sufficient to facilitate the outcome desired vis-a-vis the third stakeholder community (e.g., employers).

As a primary stakeholder in the EofL Framework, colleges and universities represent the bridge between students and employers; as such, they should feel the greatest urgency to build a more tightly integrated evidence of learning ecosystem. That said, the diversity of institutional contexts and priorities, along with the complexity of integrating expectations and practices within the EofL Framework, reflects the challenges facing college and university leaders today.

Historically, colleges and universities have been the record keepers for students' academic performance and postsecondary degree and certification attainment, providing these records for current and former students as requested and required. In most cases, these records—which stand as evidence of learning by an individual—have reflected exclusively the academic courses and experiences completed at the institution and the credit earned through transfer articulation or other institution-specific credit-approval processes.

The innovative initiatives occurring across the EofL Framework threaten to upend long-standing institutional practices. Rather than cede to these new market participants, higher education institutions have an opportunity to reassert their role as stewards of quality and of students' accumulated evidence of learning. This role requires institutions to assess their current support of student (and employer) needs. It requires an ability to think beyond any single institutional set of needs and determine where and how interinstitutional efforts make sense, potentially leading to broader systemic initiatives. It requires embracing employers and industry as core partners and determining how best to bridge the academic world with the world of work. It requires engaging with innovative solutions, tools, and services that are spurring changes in the existing infrastructure for measuring, capturing, and presenting evidence of student learning.

No one institution can tackle all these issues at once. However, by proactively engaging with core stakeholders—students and employers—to identify the most critical gaps and opportunities, colleges and universities can establish a plan for strengthening their local evidence of learning system. The progress and benefits generated from these institutional efforts will help make visible the initiatives and alliances necessary to shift from local to systemic considerations in pursuit of the broader transformation of current evidence of learning practices.

Notes

- Tyton Partners proprietary data and analysis.

- Gallup and Lumina Foundation, "What America Needs to Know about Higher Education Redesign," February 25, 2014, pp. 25, 29.

- "About Us," LinkedIn; Society for Human Resource Management, "SHRM Survey Findings: Social Networking Websites and Recruiting/Selection," April 11, 2013.

- The Campus Computing Project, "The National Survey of Computing and Information Technology," October 2013, p. 14.

- National Association of Colleges and Employers, "2012–2013 Career Services Benchmark Survey for Colleges and Universities," April 2013.

Adam Newman is Managing Partner and co-founder of Tyton Partners. He has more than twenty years of experience in strategy consulting, market research, and investment banking in the education sector and began his professional career as a K–12 educator and athletic coach at schools in Boston and New Orleans.

© 2015 Adam Newman. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 50, no. 6 (November/December 2015)