Unlike students in small online courses or unaffiliated students in MOOCS, distributed flip students might not use community features. If MOOCs for blended learning are to fully realize the potential of online communities, we must investigate alternative forms of community that are more loosely coupled to content sequence and more distributed in terms of power.

Michael Caulfield is director of Blended and Networked Learning at Washington State University. Amy Collier is director of Digital Learning Initiatives in the office of the vice provost for Online Learning at Stanford University. Sherif Halawa is a PhD student in the Image, Video, and Multimedia Systems research group at Stanford University.

Over the past year, a consensus has developed that one of the primary applications of massive open online courses (MOOCs) will be their use in blended learning classrooms.1 In part, this makes sense: the initial Stanford University experiments that led to the development of Coursera/Udacity-style MOOCs were focused on blended use by Stanford students, and the associated technologies might be a good match for blended scenarios.

However, with the use of these materials across multiple universities and colleges, new factors emerge. Materials are being used in classrooms for which they were not explicitly designed and shared among partners with very different local conditions. This pattern of reuse, which we call the "distributed flip,"2 raises implementation and integration concerns not present in either simple (single-institution) blended designs or purely online scenarios. It also offers potential for connected learning experiences beyond those of simple blended scenarios.

To better discover the issues that distributed flips raise — and how those issues are being dealt with — we examined Stanford's backend data, student surveys, and faculty reports.

Student Use of Community in Distributed Flips

Stanford's Class2Go (now OpenEdX) platform contains many courses and resources that faculty around the world have used to flip their courses. In working with the professor of one such distributed flip, we were able to pull activity records for 26 students in her class, which was a computer science class using an introduction to databases MOOC. Pulling these records gave us a better sense of what student behavior looked like when MOOCs were used for blended learning.

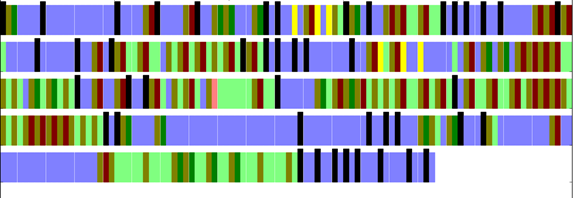

Figure 1 shows one student's activity in a distributed flip using a visualization that one of us (Sherif Halawa) developed. The image represents the student's interaction with the MOOC platform as follows:

- The black bars indicate the beginning of individual sessions — here, the student engaged in 44 separate MOOC sessions.

- The blue bars (which here often blend together in blocks of five) indicate video-watching activity within those sessions.

- The various shades of red, pink, brown, and green are various activities involving automated assessments.

Figure 1. A visualization of one student's distributed MOOC activity

And the yellow bars? That's forum activity. In this case, the student visited the forums in two of her 44 sessions, and both visits seem to have been motivated by getting a wrong answer on a question (the red bars preceding the visits indicate a failed assessment).

Although the level of forum use in this example is quite low, if anything, this student's two forum visits probably overstate the level of use we found when we looked at the class as a whole. In the 26 records we analyzed, most students made extensive use of the videos and assessment tools. Yet 62 percent of students used the forums for one session or less; a full quarter of the students did not visit the forums at all. Among students visiting the forums more than once — our sample's forum-engaged subpopulation — the median number of visits was a paltry four.

In other words, while many MOOC features were well used by the students, the community features were not used much at all. For all intents and purposes, the blended classroom students were using the MOOC as something more akin to Open Educational Resources or courseware.

It's possible this pattern is localized to this course, or this class, but we doubt it. In talking with faculty who have used a variety of MOOC platforms to flip their classrooms, the stories we heard repeatedly support what the above graphic shows: students engage with the videos and automated interactive elements, but make little use of the forums.

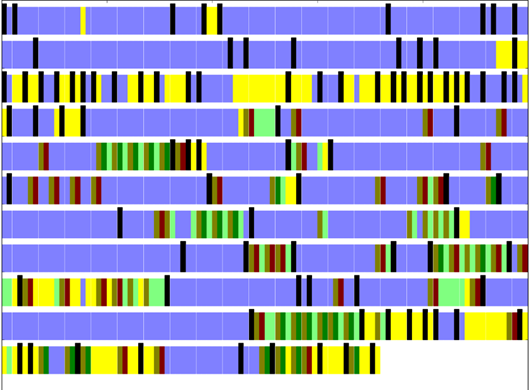

Compare this to the behavior of MOOC students taking the course on their own, without the benefit of a local class. These students, who we refer to as unaffiliated students, display a markedly different behavior pattern. Figure 2 displays fairly typical activities of unaffiliated completers who finish courses on their own.

Figure 2. Activities of a typical unaffiliated student

Obviously, multiple differences exist here, including almost twice the number of sessions and more evenly spaced testing events. However, the forums use here is perhaps the most striking element. About 70 percent of the student's sessions involve some forum use, and many sessions contain nothing but forum use. In comparison to the "one or less" pattern of forum use we saw in the flipped scenario, this student used forums in 56 sessions.

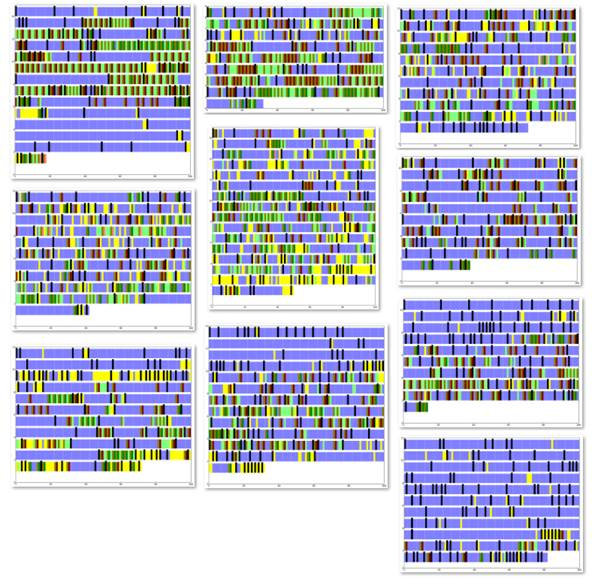

Are these differences typical? In the course we reviewed, they seem to be. Flipping through the activity charts of unaffiliated completers, we found similar distributions of forum visits. Figure 3, for example, shows 10 randomly pulled records of unaffiliated students from the same MOOC in which our blended, affiliated students had a median number of one forum session.

Figure 3. The activities of 10 randomly selected unaffiliated students

Although not all the representations in figure 3 are as striking as our first unaffiliated student example, all contain vastly more forum activity than our blended example. The figure on the bottom right, for example, might look sparse, but it actually contains 29 sessions with some level of forum activity.

Clearly, something is going on here.

Issues of Relevance and Temporal Rigidity

Why do distributed flip students not use the MOOC community features that often prove useful for students in small private online courses and for unaffiliated students in larger MOOCs? We interviewed professors using MOOCs in their blended classrooms both formally (in February 2013, as part of a research project with our colleague Helen Chen3) and informally, and we identified two major reasons.

First, it became clear that students in these flipped classes had numerous other options to receive assistance and instruction, and in many cases, they were working as part of a classroom team. As one student wrote in a post-course survey,

"I think [the students in the class] helped each other a lot more than in other classes because it became more of a self-teaching dynamic and students that knew certain topics and concepts better than others helped and taught the other students."

Another student, talking about increased interactions with the instructor as a result of the distributed flip said, "Most of the learning was outside the classroom so this method enforced us to go to office hours and spend more time with the instructor clarifying any doubts we had about the content of the videos."

Author Amy Collier talks about the distributed flip student survey findings (1:15 minutes).

Given these resources, it's likely that the online peer-support that MOOCs provide is redundant in these blended scenarios — you don't need to contact a student in Brazil about a tough assignment when your classmate lives two doors down from you, your friend in the class is available on Facebook, and a teacher can answer questions face-to-face twice a week.

Second, and perhaps more interestingly, it turned out that such cohort-based global forums are often ill-suited to serving local classes. The MOOC's centralized design, in which everyone is assumed to be on the same lesson at the same time, can be a barrier; it is actually quite difficult for multiple institutions to synchronize classes exactly. Semester start times might be different, or a class on a semester schedule might be interested in a quarter-based MOOC. Pacing was an issue for at least one professor we talked to, with the Stanford class going at a faster clip than the students could keep up with (a recent San Jose State University experiment showed similar problems). Prerequisites and course emphasis might also differ across institutions. Such factors led all instructors we interviewed to eventually offer their courses "out-of-sync" with the global MOOC cohort. And that out-of-syncness might have, in turn, further eroded the community's usefulness to students. The sense of being part of a larger class is likely to disappear if you are working through an entirely different set of lessons in your local cohort.

Professor Patti Ordoñez-Rozo discusses her experiences teaching a distributed flip class (52 seconds).

From Cohort to Community?

These results should certainly be taken with a grain of salt. This is a fairly informal study of one class and is meant to explore the issue rather than resolve the question. But, given that the multiple measures we have used to explore this issue (faculty interviews, student surveys, and backend data) all point to relatively low use of student forums by distributed flip students, it's worth asking how we might rethink MOOC community in flipped classrooms in a way that differs from both small private forums and large global ones. In particular, it's worth considering possible roles for the online community to play in MOOCs that are neither redundant nor excessively tied to a rigid sequence.

We believe that several models could inform the design of MOOC communities so as to render the communal experience more relevant to distributed flip students. We list those models here, with a short explanation of their benefits. In general, all of these models move the community's focus from strictly sequenced events and peer support for weekly exercises to less temporal, more communal endeavors.

Connectivist MOOCs

Although we have here referred to Coursera/Udacity/Class2Go experiences as MOOCs, the term was first used for connectivist MOOCs. These cMOOCs are more flexible experiences, connecting many users around content sequences and discussion topics, but structuring them to give users more control both over the discussion environment and their engagement with it.4 As one of us has noted elsewhere,5 the cMOOC experience's distributed, flexible nature produces more robust and persistent communities largely because the community's focus is less on the course itself (such as, "what is the answer to question number five?") and more focused on the intersection of the course content with the lives and work of the students.

A cMOOC community wrapped around a distributed flip could provide an integrative layer to a course design, helping not so much to make basic material more comprehensible as to make the work more meaningful.

Loosely Coupled Cross-Institutional Courses

Many organizations have experimented with cross-institutional courses — that is, related courses that run simultaneously at multiple institutions and are connected by an online community of students and faculty. Some recent examples include:

- The Looking For Whitman Project (2009): Four universities taught courses on Walt Whitman from different historical, cultural, and literary perspectives, but were united through a common community based on syndication and aggregation of student reflection and complementary course assignments.

- Ds106 (2010–present): In this open course, both affiliated and unaffiliated students are encouraged to build community around an assignment bank model. That is, students choose the assignments they want to do, and do them in any order they choose. Students are drawn into the community by being able to review all instances of the chosen assignment executed by students before them. The more students who have executed the assignment, the richer the inspiration for students' current work.

- Dialogues on Feminism and Technology (2013): This "Distributed Open Collaborative Course" runs concurrently on 17 different campuses, connected by a central digital commons. Labeled the Anti-MOOC by some,6 it is in fact very similar to a cMOOC, although more institutional in a number of interesting ways.

The key element connecting experiments such as these is that the differences in the local versions of each class are seen not as deviations but as net benefits to the cross-institutional community; the dialogue among students in different classes is meant to foster a diverse community of learners.

Public Work as a Community Foundation

A final, related category worth mentioning are communities that focus on giving students opportunities to engage in authentic, collaborative work. The University of Virginia's Darden School of Business, for example, offered Foundations of Business Strategy through Coursera, a MOOC that connected students with real-world businesses requiring strategic analysis; as a final project, students worked together to produce this analysis.7 In its "Storming Wikipedia" project, the Feminism and Technology course discussed above will have students from all of its sections edit Wikipedia articles for gender bias.8 As a final example, two of us are involved with the Water106 project, a cross-institutional, cross-disciplinary, issues-based community that will attempt to connect schools around the world by engaging them in projects around issues of water supply and quality. Example projects include Waterfeed [http://water106.net/newarticles/], a crowd-sourced, student-managed site that aggregates and summarizes recent news on water policy, science, and technology.9

In these cases, the community can act to connect students to engaging, real-world opportunities that might be impossible to provide in the context of a smaller, face-to-face course.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Although our results and conclusions are preliminary, we hope they will spur similar investigations of distributed flip models at other universities and inform new designs for connected learning communities. Much has been written about online community behavior in small, private online courses and in MOOCs, but little information exists about MOOCs used for blended learning. As our research indicates, the current design of online communities might not be adequately serving the needs of distributed flip students.

As more is learned about how best to interweave local and online learning communities, design principles for MOOCs will evolve, but it will be up to the institutions and faculty offering those MOOCs to respond. Based on our findings and experiences working with Stanford faculty on MOOC design, we recommend the following near-term steps to designing MOOCs for blended learning:

- Talk to faculty about the distributed flip model and encourage them to think of local learning communities as a targeted audience for their MOOCs.

- Adopt open educational practices in support of your MOOCs and, in particular, assign clear reuse guidelines for your content aimed at clarifying opportunities for local learning communities.

- Include potential content and community partners in MOOC design. If you are hoping that other universities will adopt your MOOCs for their distributed flips, reach out to potential partners and include them in design and research plans.

- Consider forms of online community beyond the discussion forum. Such new forms might aim to serve less of a support function and more of an integrative function, exposing students to a broader range of experiences than those to which they otherwise might have access.

- Michael Feldstein, "MOOCs, Courseware, and the Course as an Artifact," e-Literate, April 12, 2013.

- Michael Caulfield, "The Distributed Flip," presentation for InstructureCon 2013, Hapgood, June 26, 2013.

- Amy Collier, "What Happens in Distributed Flips? Investigating Students' Interactions with MOOC Videos and Forums," The Red Pincushion, May 2, 2013.

- George Siemens, "MOOCs Are Really a Platform," elearnspace, July 25, 2012.

- Michael Caulfield, "xMOOC communities Should Learn from cMOOCs," ERO Blogs, EDUCAUSE, July 20, 2013.

- Scott Jaschik, "Feminist anti-MOOC," Inside Higher Ed, August 19, 2013.

- Zafrin Nurmohamed, Nabeel Gillani, and Michael Lenox, "A New Use for MOOCs: Real World Problem Solving," Harvard Business Review, July 4, 2013.

- Nina Liss-Schultz, "Can These Students Fix Wikipedia's Lady Problem?" Mother Jones, August 23, 2013.

- Michael Caulfield, "Water106: A Distributed Approach to Issues-Based Education," Slideshare, August 15, 2013.

© 2013 Michael Caulfield, Amy Collier, and Sherif Halawa. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.