Key Takeaways

- Education built around digital portfolios not only ties together various student-generated artifacts into a coherent whole but also creates an environment in which technology use has a clearly identified purpose.

- Hundreds of services provide free hosting and website creation tools and are ideal platforms for digital portfolios because they can support just about any type of digital content.

- Turning consumers of knowledge into producers of knowledge transforms learning into an active experience.

Digital portfolios have become increasingly widespread over the past few decades, and with Web 2.0 tools becoming easier to use, the read/write web has transformed passive consumers of information into producers. This transformation holds enormous potential for pedagogy. Education built around digital portfolios not only ties together various student-generated artifacts into a coherent whole but also creates an environment in which technology use has a clearly identified purpose. Well-designed learning environments organized around published digital portfolios can increase not only academic achievement but also intrinsic motivation, student autonomy, collaborative learning, and digital literacies. I teach a course utilizing the published digital portfolio system.

Background and Development

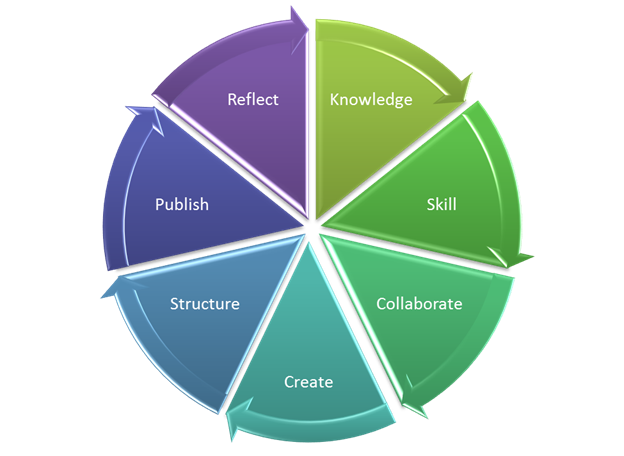

Since the advent of constructivism, education has seen a slow, steady shift from knowledge being imparted to students toward knowledge being created by students. Along with this shift has grown a need to create opportunities for students to produce meaningful artifacts. We see this best in the growing trend toward project-based learning. A portfolio is a collection of artifacts demonstrating knowledge and skills. These artifacts should be structured and presented in a format that is easy to navigate and easy to read. A portfolio's contents should be interrelated and should address one overall theme. A digital portfolio does the same thing, except that the artifacts are all in digital format. Digital portfolios hold enormous potential for structuring, organizing, and presenting digital artifacts. However, many digital portfolio projects are contained within closed systems. Some are in file format and therefore available only to those in possession of the files. Others are online but reside within password-protected environments.

The advent of what we now call Web 2.0, or the read/write web exponentially increased the ease of content production and publishing. Suddenly the consumer could become the producer. A decade ago if you wanted to create a website, you would have to learn how to use fairly difficult software — along with finding a hosting solution and managing the files — and you might even have to learn a bit of HTML. Now, with a few clicks of the mouse, a child who can't even spell Internet can create a published website. Hundreds of services provide free hosting and website creation tools. These websites are ideal platforms for digital portfolios because they can contain just about any type of digital content. Moreover, publishing to the web instantly creates a potential audience for the student.

Digital portfolios in a website format have the advantage of being able to contain embedded content (through embed codes rather than through links). This means, for example, that students can embed videos they create in YouTube or Animoto, presentations created in Prezi or SlideRocket, mind-maps created in Bubbl.us or SpicyNodes, screencasts created with Screenr or Screencast-o-Matic, and podcasts created with Chirbit or AudioBoo. One of my students, Amanda Zengel, put it this way: "Once I learned how to embed the items I wanted into my website, as opposed to simply providing links, the website seemed to come alive and be more user friendly." The distinguishing feature of many useful Web 2.0 tools is that they host the product online and provide an embed code so that students can house all of their artifacts in their own digital portfolio website.

Intrinsic Motivation

One powerful aspect of published digital portfolios is that they increase intrinsic motivation. Teachers can encourage but cannot create intrinsic motivation in their students. The best we can do is create an environment in which their intrinsic motivation can flourish. It is important to remove or diminish extrinsically motivating factors such as grades and competition, but it is equally important to understand the factors that can contribute to the growth of intrinsic motivation and create situations that play upon those factors.1

When students create artifacts that will be contained within digital portfolios they know might be seen by a worldwide audience, they often undergo a powerful shift from extrinsic motivations — such as grades and teacher approval — to intrinsic motivation. Turning consumers of knowledge into producers of knowledge transforms learning into an active experience. Recognizing the potential for a wider audience, students are transformed into teachers, which in turn enhances their own learning.

Autonomy

Building learning activities around published digital portfolios allows for greater student autonomy. Not only can students individualize the look and feel of their portfolios through templates and design options, they can also enjoy increased individualization of content and the delivery format of portfolio artifacts. Autonomy, in both cognitive and emotional terms, is related to academic achievement.2 Increased autonomy is effective because it shifts the ownership of the learning toward the student. As Erika Patall and her co-investigators noted, "Choices that involved making decisions regarding the actions one takes were found to be effective because they also enhanced perceptions of having an internal locus of causality and volition."3 Allowing students to make more choices in their learning can result in learning achievements in areas beyond those they have chosen as a focus.4

Collaboration

Another aspect of published digital portfolios is that collaborative learning is not only supported but also encouraged by the platform itself.5 Published digital portfolios enable collaboration on two fronts:

- First, many Web 2.0 tools let multiple users work on a project simultaneously.

- Second, because the work is published, students' classmates and peers at other locations can provide instantaneous feedback.

In a collaborative learning environment based on sociocultural learning theories, higher academic achievement levels are attained and "students' independent and reflective thinking skills will be improved."6 It is often said that we learn best when we do, but perhaps it would be more appropriate to say that we learn best when we do together.

Digital Literacies

My personal favorite among aspects of published digital portfolios that make them powerful learning tools is that students can build digital literacy skills incidentally while tackling the learning objectives at hand. Educators now have the task of not only teaching content, as we did in the past, but also of teaching our students — in the words of Megan Poore — to "produce as well as consume digital culture, and they need to be taught how to use digital tools for communication and collaboration purposes, and to contribute in ethical ways — through a greater knowledge of themselves and a shared knowledge of others — to the collective intelligence of the knowledge space."7 Digital literacy stands at the point of confluence of three domains upon which digital media have a major impact: the technical domain, the cognitive domain, and the social-emotional domain.8 In other words, students broaden their experience and become better digital citizens.

Much of the information available on the Internet consists of opinion, hearsay, unfounded assumptions, purposely misleading claims, and complete falsehoods. But there is a vast amount of valuable information available through the Internet, too. The digital citizen must be able to evaluate the reliability of the source of any piece of information. Being able to efficiently gather, manipulate, and interpret information is an essential skill in today's connected world.

Privacy and Security

The digital world holds many dangers as well as possibilities. Therefore, digital citizens should be able to protect themselves and maintain control over their online identity. Social networking tools, two-way or multiparty digital communication tools, and interactive broadcast tools such as blogs have changed the way we communicate. Digital citizens should be able to use these tools with fluency while maintaining conscious control over their own online identity.

If a digital portfolio is kept behind a password-protected environment or in a file format, issues of privacy and security play a smaller role. However, if the digital portfolio is in published website format, wonderful opportunities arise to help students better understand privacy and security issues while developing their skills at managing their online identity. Because their work is accessible to anyone with an Internet connection, they should be made aware of these issues. For example, teachers can let students work under pseudonyms and prohibit them from publishing anything that would identify them. Most importantly, teachers should make sure students understand that they should never publish personal information such as addresses, telephone numbers, e-mail addresses, or personal photographs. The goal is to encourage such practices in managing one's online identity to carry over into students' personal use of technologies.

The "Write" Part of the Read/Write Web

Being able to "write" in the digital age entails more than constructing well-crafted sentences, paragraphs, and essays. Rather, it means being able to create digital content that conveys information effectively for dissemination through websites, blogs, wikis, online presentations, illuminating graphics, audio content, and video content. This addresses the highest level of Bloom's Taxonomy. By producing content, our students will become better consumers and evaluators of content.9

Published Digital Portfolio in Action

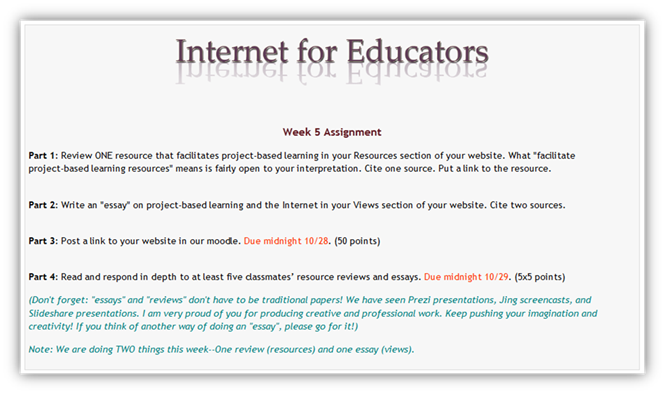

A concrete example of published digital portfolios in action is the Internet for Educators class I teach at several local universities and colleges. My students are either teachers-in-training or experienced K–12 teachers. The class is conducted online through a learning management system. Each week's lesson consists of an overview (lecture), a list of resources, and a discussion forum whereby students submit their work for the week and give feedback to their classmates.

During the first week of class students set up their basic portfolio structures. The first step is to have the students create accounts with a free website-hosting service such as Weebly, Yola, or Wix. If the portfolio will be built incrementally over an academic year or term, it will need a basic page structure. In my class I have the students build a structure with blank pages entitled:

- Standards (NETS-S and NETS-T)

- Internet Resources

- Collaboration

- Project-Based Learning

- Digital-Age Assessment

- Primary Sources

- Creativity

- Digital Literacies

- Professional Development

These pages will be populated with artifacts created weekly.

After the first week of class, we start focusing on a topic. Students create artifacts for each topic using a different Web 2.0 tool each week. For example, in the second week they study and discuss the National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers (NETS-T) issued by the International Society for Technology in Education. They create a Prezi or SlideRocket online presentation on the topic, which they then embed on the Standards page of their digital portfolio. Then they post a link to that page in the discussion forum, after which they give in-depth feedback concerning five classmates' presentations. Subsequently they delve into other topics, each addressed through online presentations they create using the different Web 2.0 tools. In this way they not only build their technical skills but also engage simultaneously in research, thought, and discussion of important topics in education that are affected by technology.

As the weeks go by, the digital portfolio websites mature. The shared feedback covers not only content but also other aspects such as design considerations and accessibility. During the final few weeks of class, students are asked to add one more page on a topic of their choosing and populate it with content created using any embeddable Web 2.0 tool. Then they take all the feedback they were given all along over the term from their classmates and instructor and improve their portfolios.

Each student's final product is of extremely high quality. It has been painstakingly built over an extended period, one artifact at a time. It has been reviewed and critiqued by classmates and the instructor. It is polished enough that they feel confident in using it for future purposes such as job hunting or professional development. Most students are proud of their digital portfolios and send the link to friends, family, and colleagues.

Student Feedback

The feedback I most commonly get after this course is that students started out with a fear of the technology; by the end, however, they are surprised at how easy the whole process turned out to be. My favorite feedback is having students tell me that they have started using published digital portfolios with their own classes, usually modeled on the process we used in our class.

"I just finished taking an educational technology course which miraculously managed to evolve in my head from a dreaded summer class to an incredibly fun and useful learning experience. . . . Whenever I asked [colleagues] if something like this could be done, I was told that it would be too difficult. The process of creating this digital portfolio has given me the confidence to know that teenagers aren't the only ones who can be digitally literate. . . . The entire process of creating my digital portfolio was liberating. For so long, I'd been told that I had to work under the 'one size fits all' parameters that my district had set for everyone. Now I'm free to customize my website to meet the needs of my students' families."

—Jennifer House

"As a bilingual teacher, I am always looking for new ways to present language and information, while at the same time exposing my students to technology that they may not have otherwise discovered. Many of my students do not have a computer or Internet access at home. When they reach high school and higher education, they will not only be working fully in their second language, but they will also be expected to produce documents and projects on the computer. It is my job to show my students how fun technology can be, and how it can be applied to their learning now and in the future. This class helped me find the tools to do that."

—Erica Heisler

"I truly enjoyed learning how to use the technologies in this course. It gave me the opportunity to learn about new Web 2.0 tools and be able to combine them with effective practices used in English Language Development to meet not only students' but parents' needs as well."

—Emily Beiser

"My website has a very specific audience, but considering how easy it was to build (after I came up with the concept), I will definitely be using this technology in my classroom. It is a great way to communicate with a group and share resources."

—Amanda Zengel

Conclusion

Over the past two decades digital portfolios have emerged as a powerful tool for helping students organize, create, manipulate, design, evaluate, and present knowledge. As our classrooms become increasingly populated with digital natives, it is imperative that we educate them in their native language. This means not only working in digital media but also working as producers of information, collaborators, and self-directing learners. The digital portfolio in a format to be published openly online is an ideal means for applying technology to serve a larger-picture educational purpose, thereby helping our students flourish academically and personally.

Sample Student Screencasts

Jennifer House: http://screencast-o-matic.com/watch/clj30esrM

Emily Beiser: http://www.screenr.com/b0b8

Amanda Zengel: http://www.screenr.com/SiY8

Jaynie Cole: http://www.screencast-o-matic.com/watch/clj3FxsqU

Erica Heisler: http://www.screenr.com/vpb8

- Pieternel Dijkstra et al., "Achievement Motivation Revisited: New Longitudinal Data to Demonstrate Its Predictive Power," Educational Psychology 29, no. 5 (August 1, 2009): 561–82.

- E. A. Skinner and Una Chi, "Intrinsic Motivation and Engagement as 'Active Ingredients' in Garden-Based Education: Examining Models and Measures Derived from Self-Determination Theory," Journal of Environmental Education 43, no. 1 (2012).

- Erika A. Patall, Harris Cooper, and Susan R. Wynn, "The Effectiveness and Relative Importance of Choice in the Classroom," Journal of Educational Psychology 102, no. 4 (2010): 896–915.

- Erika A. Patall et al., "Student Autonomy and Course Value: The Unique and Cumulative Roles of Various Teacher Practices," Motivation and Emotion, Online First (May 30, 2012), Springer Netherlands.

- John Chelliah and Elizabeth Clarke, "Collaborative Teaching and Learning: Overcoming the Digital Divide?" On The Horizon 19, no. 4 (2011): 276–85.

- Li Wang, "Sociocultural Learning Theories and Information Literacy Teaching Activities in Higher Education," Reference & User Services Quarterly 47, no. 2 (Winter 2007): 149–58.

- Megan Poore, "Digital Literacy: Human Flourishing and Collective Intelligence in a Knowledge Society," Australian Journal of Language & Literacy 34, no. 2 (June 2011): 20–26.

- Wan Ng, "Can We Teach Digital Natives Digital Literacy?" Computers & Education 59, no. 3 (November 2012): 1065–78.

- Zac Chase and Diana Laufenberg, "Digital Literacies: Embracing the Squishiness of Digital Literacy," Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 54, no. 7 (April 2011): 535–37.

© 2012 Jonan Donaldson. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license.