Key Takeaways

- Wireless devices in the classroom threaten to distract student attention but also offer opportunities for student engagement.

- Faculty use different methods to reduce in-class distractions, up to mandating no use of wireless devices during class sessions.

- To increase student engagement using wireless devices, faculty employ creative options for making wireless devices part of instruction, from cell phones as clickers to laptops for on-the-fly web research.

The path of technology integration in education is lined with disruptions on one side and opportunities on the other. Technology teams work to bring useful technology into teaching, all with good intentions, only to encounter unwanted side effects such as distraction and disruption in the classroom. The challenges loom large in classrooms with wireless connections, especially when universities give students ubiquitous Internet access and sometimes even the devices for such access.

Mobile phones, for instance, are considered distracting because of problems with ringing during class, cheating, or multitasking,1 and the camera that comes with many phones can raise privacy issues as well. Similar complaints might also be made about laptops in the classroom. Laptops occasionally make sounds if students have forgotten to turn off the volume, and the laptop screens can become walls between students and professors. Students performing multiple tasks (instant messaging, Facebook updating, and so forth) are also blamed for distracting other students from concentrating on the lectures or classroom discussions.

Technology-enabled distraction is a problem that no educator can afford to ignore as ubiquitous computing and mobile learning environments become commonplace. From the literature and my own experience working with professors, I have found a whole spectrum of methods for dealing with such distractions, ranging from technical control to pedagogical innovation. In this article, I discuss these methods with a special emphasis on engaging students to minimize the negative effects of distraction by laptop computers or other wireless devices.

Restrictive Methods

Some schools use prohibitive methods to prevent or restrict uses of technology that might disrupt or distract students during class.

Ban Laptop Use

Some schools or individual faculty do not permit students to take computers or mobile phones into classrooms because of the problems of distraction and disruption. Some pioneers in laptop programs have even ended their programs. For instance, the Liverpool Central School District of New York, one of the earliest districts to adopt a laptop computer program, decided to phase out its high-school laptop program between 2007 and 2010 after hearing teacher complaints of student abuse and the distractions caused by the laptops in class.2

In K–12 school districts, the district's decision will have an immediate impact on student access to wireless devices. However, I recently talked to a teacher in a Texas high school who said that it is challenging to ban mobile devices because of frequent exceptions (for instance, in case of emergencies), which rendered the policy hard to enforce. School districts will need to explore more sophisticated approaches to manage the issue than outright bans.

Banning laptops or mobile phones is more challenging in colleges and universities, where students (mostly adult) have greater flexibility and often more personal resources enabling them to own laptops and mobile phones. Professors can ban the use of laptops or mobile phones in their classes, but this will penalize students who use computers to take notes, search class-related materials, or take online quizzes. Laptops are especially useful for professors who allow students to take standardized tests online, in the classroom, in a proctored environment (which is now increasingly required for reasons of legal compliance and academic integrity).3 Because of the potential opportunities for learning, some universities have taken countermeasures against banning laptops in classrooms.

Students have also expressed concerns about such bans. In a recent survey of mobile learning at Oklahoma Christian University, we found that many students expressed a strong preference to bring laptops into their classrooms so that they could take notes, for example. One student wrote, "More professors need to allow laptops in their classes. They say they ban them because they are a distraction, but it should be up to the student to put the effort into the class." Other students disliked having laptops in the classroom because better methods are not available to handle the distraction issue. A one-size-fits-all approach to bans, though, makes some students feel punished for something they have not done. One student wrote in the survey, "…allow us to use our laptops to take notes. We are adults, and if someone decides to waste time on the Internet instead of taking notes, that is their choice, but the rest of us shouldn't be punished for it."4

Shut off Wireless

Instead of banning laptops, educators can turn off wireless connections, allowing students to use their laptops to take notes and not much more. The University of Chicago Law School, for instance, eliminated Internet access in the classroom "in order to ensure the value of the classroom experience" because "students may overestimate their ability to multi-task during class and … some students have expressed distraction due to their peers' use of computers during class time."5 The law school of the University of Memphis also banned laptop use in the classroom, which caused some students to sign a petition to the American Bar Association complaining that they were denied "up-to-date education."6

Once again, this policy eliminates learning opportunities that would be possible with wireless access enabled. To further complicate the issue, some courses might depend heavily on Internet connectivity. What if, for instance, a professor is teaching a group of students in the classroom and simultaneously a group outside the classroom via a virtual conferencing application such as Adobe Connect? This is a real scenario at Oklahoma Christian University in a number of graduate programs with nontraditional students. Since the video conferencing is server-based and dependent on Internet access, cutting off wireless connections would make such dual-mode teaching impossible.

Problems with Restrictive Methods

Practices to ban use of mobile devices raise doubts in many constituencies. In a keynote speech at the mobile learning summit ConnectEd hosted by Abilene Christian University in February 2009, Jason Ediger, Director of iTunes U and Mobile Learning of Apple, said that educators have turned school classrooms into something like airplanes. Students accustomed to using technologies all the time enter classrooms and are forced to turn off their digital devices and sit tight. Another speaker at the conference echoed this message: Harvard professor Eric Mazur, who used student response devices to promote peer instruction in the classroom, commented that laptops and smart phones do not cause more distraction than windows through which students look at birds and flowers, "yet you don't seal the windows just because of that." Podcasts of the ConnectEd Summit are available online.

It does not seem likely that laptops, wireless connections, and various kinds of wireless access devices (such as smart phones, podcast players, PDAs, pocket PCs, tablet PCs) will disappear from universities. It is much likelier that their numbers will increase, with some universities even adopting campus-wide mobile learning programs.7 Mobile phones and laptops have increasingly become commodity products and easily available. Students are increasingly comfortable using wireless devices to organize their academic work, personal lives, and eventually their professional activities once they graduate into the workforce. We have actually reached the point of no return in usage of such technology.

Additionally, a confrontational or restrictive policy might create a "professor versus technology" perception that will not do professors much good, hurting student-teacher relations and in some cases faculty reputation. For instance, it might cause a faculty member to impress others as a laggard in technology adoption or as someone who resists positive change. Additionally, prohibitive approaches could send the message to students that they are not trusted to take responsibility for their learning. Last but not least, some professors are frequent users of classroom technologies, and it would be hard to cut their ties to technology in the classroom.

Distraction as Opportunity

Studies or reports about the effects of distraction often seek to correlate the use of technological devices to learning outcomes. For instance, one study found that the level of laptop use was negatively related to several measures of student learning, including self-reported understanding of course material and overall course performance.8 Similarly, a Chronicle of Higher Education report indicates that students taking laptops to classrooms might appear to be taking notes, but actually were doing activities unrelated to class work, such as sending e-mails or surfing the Internet.9

Some interesting questions remain to be answered: Whose fault is it if distracting activities are going on in the classroom? What caused the distractions other than the availability of technology? Will alternative distractions occur if the technological tools are removed? Without implying that students are always right, I would say that the issue gives educators a reason to reflect on their own teaching or, rather, the instructional process as a whole. Viewed this way, distractions caused by computers might be the result of a failure to involve students in the classroom rather than the reason they are not engaged.

The distractions blamed on mobile technology could present opportunities for change in the classroom. With many of the world's best professors sharing their video lectures through educational portals such as iTunesU, Academic Earth, and the recently launched YouTube EDU, students have access to the best lectures online in many subject areas. These might be the real "distractors" for professors if they do not reform their teaching. In an age of abundance, professors might find it useful to reflect on ways to engage students who do not lack access to learning opportunities but instead have an abundance of choices.

Integrative Methods

Learning with computers or smart phones is a tool-mediated social function. Conflicts and disturbances occur as various activities take place, but they also create opportunities to change a system because in social systems "equilibrium is an exception and tensions, disturbances, and local innovations are the rule and the engine of change."10

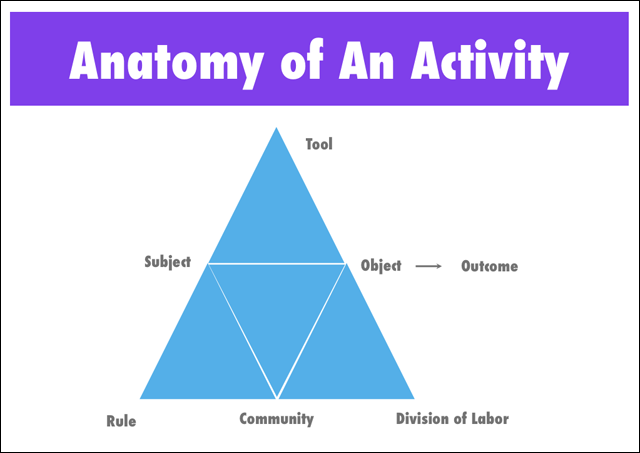

Yrjö Engeström uses an "extended activity theory" framework as an analysis scheme for tool-mediated social activities.11 In this framework, the unit of analysis is not a particular tool but the entire "activity" involving the tool, subject, object, outcome, rule, community, and division of labor, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Engeström's Extended Activity Theory

As the figure shows, there are several points of attack to improve a tool-mediated activity. In the case of classroom teaching with computers or other mobile access devices, a focus on tools has been one of the main restrictive methods pursued. Instead, educators should look at other factors in the model, for instance, the rules to use in the classroom to guide appropriate use, community efforts to brainstorm productive uses of technology, divisions of labor among faculty and technology staff, new teaching methods to engage students (subject), and adaptation of course materials to better deliver content for digital natives (object). Using this framework as a launch pad in thinking, I suggest the following methods to allow use of computers or mobile devices in the classroom by harnessing their powers while keeping distracting effects to a minimum.

Use Filtering Applications ("Tool")

Applications such as the Respondus LockDown Browser can help when faculty want students to bring their laptops to the classroom to take online exams (especially classes with large enrollments). Faculty members at Oklahoma Christian University use this program, which locks other applications during an exam. Similar applications (when invented) could filter out distracting factors during class if teachers assign a computer-assisted activity that does not require more than one application.

The flip side of using such programs is that an unstable wireless network might disrupt an exam or another online activity. When faculty use LockDown Browser, they expect reliable wireless service and on-site support from the technology team until they feel comfortable using the program.

Enable Switching Networks On and Off ("Division of Labor")

Technology-enhanced classrooms can be managed collaboratively between faculty and the technology team. While professors focus on teaching and learning activities, technology teams can work on solutions for smart control of technology access in the classroom. Some universities have made this collaboration highly granular. Bentley College, for example, allows faculty to choose one of five settings: turn off Internet access but allow e-mail access; turn off e-mail access but allow Internet access; disable Internet and e-mail access but allow computers to reach campus web pages; shut off all access; or allow all access.12 Oklahoma Christian University also has methods to turn certain applications on and off, such as instant messaging services, based on faculty requests.

The switch option, however, might require a certain level of technical sophistication on the part of faculty in deciding what to leave on or off and then actually controlling the switches. This option could require an explicit division of labor between faculty and technical staff, which can become logistically challenging but well worth the effort. It also might require some tolerance of the initial chaos until everyone is comfortable with the method.

Contract with Students ("Rule")

Faculty members may allow laptops or other wireless devices in the classroom, but set proper boundaries to tell students what is acceptable and what is not. The School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University includes clauses in the syllabi to warn students against inappropriate use of technology in the classroom. For example:

If your cellular phone is heard by the class, you are responsible for completing one of two options: 1. Before the end of the class period you will sing a verse and chorus of any song of your choice or, 2. You will lead the next class period through a 10-minute discussion on a topic to be determined by the end of the class. (To the extent that there are multiple individuals in violation, duets will be accepted.)13

This rather light-hearted approach addresses a problem that could create tension between students and professors. Instead of mandating the way students learn, professors can actually contract with students to elicit their self-regulation, supporting the shift in the paradigm of teaching from teacher-centered instruction to student-centered learning. Contracting with students implies that faculty trust individual students to make the right choices. Having such learning contracts is an important part of individualized, self-directed learning that works well with college students who are adult learners in particular.14

Educate the Community ("Community")

Educators can use mass training to educate students about the social norms of technology use in the school community. Students do behave differently. Some use their computers or mobile devices productively in the classroom, taking responsibility for their own learning and showing consideration for others who might be affected by their behavior. Some rude technology-related behaviors can be prevented or minimized if students have learned about community norms through workshops, written guidance, or orientation sessions.

Michael Bugeja recommends orientations on "interpersonal intelligence" to educate students about classroom rules regarding technology use and misuse.15 Such training can happen in a physical classroom or online. It does not have to be an extensive lecture series on technology and culture. It can be a small module embedded in a course website or on the IT services website, or simply an instructional video to show desired behavior. Another good method is to provide orientation for incoming students and faculty on acceptable technology-use practices and web and Internet etiquette.16 Such training will not eliminate all issues of disruption, but at least they set proper expectations and reduce inappropriate uses of technology.

It also helps to put peer pressure to work by providing peers' opinions about in-class distraction or disruption by classmates' inappropriate use of devices. These views could be made known discreetly (without invading student privacy) through school newspapers, newsletters, survey reports, student blogs, or other formats that can educate students about social expectations of their behavior.

"Re-mix" Lectures ("Object")

Another method for engaging students is to deconstruct a traditional, 50-minute lecture by breaking it up, re-mixing it, and redistributing it in a variety of formats and settings. For instance, instructors can offer some quizzes online through a course management system. They can describe their course objectives and assignments online. They can present some generic lectures as digital videos, which are gaining traction among the educational technology community with the emergence of several types of educational outlets. These videos can expose students to content before or after class, thereby freeing class time for active learning activities.

Determining the anatomy of a lecture reveals a series of instructional tasks that can be distributed in a variety of ways. Robert Gagne described nine instructional events in an instructional sequence that includes presentation of information and processing of information.17 Professors can put the "presentation of information" or content better suited for individual study into these video lectures and devote class time to activities better suited for group time or active learning activities requiring constant feedback, such as questions and answers, discussions, general assignment feedback, group collaboration, and hands-on activities. Computers in the classroom then can become an extra resource instead of a barrier between professor and students, and there is no reason why this would hurt teaching or learning.

Involve Learners ("Subject")

Instructional technologist Dan Weiss once commented, "It's teachers who refuse to engage students well enough and who don't set proper boundaries as to what is and isn't acceptable behavior in their classroom."18 In traditional lecture-dominated teaching, students, who should be the subjects of learning, become the objects of teaching or the passive recipients of information. This kind of teaching is very vulnerable to distraction. When students feel compelled to sit through a 50-minute lecture, an occasional "distraction" might even provide a healthy balance — unless it is abused.

On March 4, 2009, 16 students from Georgia performed a "show-and-tell" to legislators on "Capitol Hill Tech Day" to prove the value of technology in the classroom. "It keeps me awake," said one student who uses whiteboards in her AP calculus class.19 Derek Bruff of Vanderbilt University devoted an entire book to using technology to create active learning environments.20 In his case, he used the clicker classroom response system. A similar approach could be used with other mobile access devices such as iPhones, iPods, or laptop computers.

Putting these devices in the hands of students can begin to increase active learning. When students are viewed as active participants in learning, distraction becomes much less an issue. With active learning, students develop their own cognitive or operative skills.21 Use of wireless laptops might even enhance "student-centered, hands-on, and exploratory learning" as well as "meaningful student-to-student and student-to-instructor interactions."22

Once we start to think beyond the traditional concept of learning as classroom lectures, many new opportunities for learning unfold. A Futurelab report summarized six types of learning supported by mobile technologies23:

- Behaviorist learning, in which mobile devices are used to create stimulus-response connections such as content delivery through mobile devices

- Constructivist learning, in which mobile devices support student construction of knowledge

- Situated learning, in which mobile devices are used in authentic context and culture

- Collaborative learning, in which students learn with their mobile devices through social interactions

- Informal and lifelong learning, which happens outside of a formal education context

- Teaching and learning support, in which mobile devices and their associated resources are used not for actual learning but for support of human performances

If institutions broaden the scope and definition of "educational value," unique uses for mobile phones, laptops, or other wireless access devices can positively affect student learning and student life in general.

Extended Uses

With extended uses, students employ their devices productively beyond their classrooms or even their campuses. In these other contexts of learning, the issue of distraction further transforms into a tool for engagement.

Turn Wireless Access Devices into "Study Buddies"

Other than "toys" for students to play with, mobile devices can become students' study buddies in or outside of class. Why shouldn't educators compete for that learning space in a student's hand? Instead of banning mobile devices, or just tolerating them, educators can use such devices as tools to engage students' minds.

Transcript: Linda Fly, Director of Nursing, on Using Computers in the Classroom

Hello! My name is Linda Fly and I am the director of nursing. I had been asked whether or not I allow computers to be brought into the classroom when I am teaching. And the answer to that is yes. I just truly feel like that students today really want some kind of interaction, and they love the technology. So I do try to incorporate computers into the class. Being in the healthcare field we were able to do some online searches to various, health-related websites, such as the CDC [the Centers for Disease Control]. There are online drug books so that students can immediately access the medicines we are talking about in class. There are various anatomy and physiology, graphics, and X-ray machines that they can actually see the images. We in the nursing field just really do love to have computer technology. So yes, I am very much in favor of students bringing their computers into the classrooms. Thank you.

Mobile phones, for instance, have been reported as a tool to help students study foreign language vocabulary.24 They can also be used to help students prepare for exams in "bite-sized" information or learning nuggets. Some wireless providers allows users to download sets of SAT flashcards, drills, and practice tests onto the handset so that no-call zones don't affect them.25 This provides students a very "handy" way to study for their tests. Such uses are especially popular in Asian countries like China, where public transportation is the norm.

At Oklahoma Christian University, we have an application called "3 by 5" that lets teachers develop flash cards as study aids for students. A professor of Greek, for instance, developed a set of flash cards for his intro-level course. The International Office also ponders the possibility of having mobile language apps for students in study-abroad programs. We also have an instant polling tool to gather student feedback from their mobile phones or other devices (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Instant Polling Tool Using Mobile Phones

To convert mobile devices into study buddies, the key is to develop applications that make it easy for faculty to create, upload, and disseminate digital content. One interesting possibility is an application to turn regular text files to speech format. The recently released Kindle 2 from Amazon has text-to-speech functions. Some professors have started to convert their text lectures into audio format using applications such as TextAloud from NextUp.com, which may include AT&T Natural Voices (supported and licensed by Wizard Software). Students report they like these audio lectures produced with text-to-speech applications. While I was working at Marshall University in West Virgina, quite a few professors used this method with positive student feedback. Most Macintosh computers have text-to-speech utilities to accomplish such tasks. Alternatively, an iPhone can be turned into a podcasting tool, which professors can use to directly record their lectures. Some podcasting vendors such as Podbean have started offering mobile versions of their podcasting service that allow users to podcast directly with their mobile phones.

Alternative presentations of course content via mobile phones or laptops might also support multiple learning styles or multiple paths to learning, which presumes that some people are better learners using different methods, such as sound, text, video, or hands-on activities. Audio learners would benefit from listening to learning content; John Traxler described such alternative methods of learning as "hands-free learning" or "eyes-free learning."26

Use Wireless Access Devices to Support Performance

In the corporate setting, some companies have ways for professionals to access their knowledge base or training materials via mobile phone. For instance, consulting company Accentuate allows their sales professionals to access resources via mobile phones.27 An electronic retailer asked their sales professionals to use a barcode scanner and PDA to access product training in their work environment.28

Not all skills or knowledge should be internalized via training or education. Some tasks are performed infrequently, yet are significant to carry out. In this case, it might be better to simply provide performance support instead of training.29 In the early 1990s Gloria Gery coined the term "electronic performance support systems" to describe support delivered via electronic means to help a person perform the task at hand.30 Mobile phones can be used to push performance aids such as video tutorials, guides, or written instructions to faculty or students where and when they need it, how they need it, and as much or little of it as they need. It is with this kind of use in mind that we at Oklahoma Christian University are developing a repository of video tutorials accessible via mobile phones. Such performance support videos will help students use various school applications without investing time to learn them.

Use Wireless Access Device for Outdoors Learning

Educators can look beyond classrooms for multiple learning opportunities that come with technology. Ann Jones and Kim Issroff described an educational activity called "environmental detectives" in which students played the role of environmental engineers using location-aware pocket PCs to investigate a toxic spill.31 A study in Taiwan looks at the positive effects of using PDAs in combination with cameras and tag readers for an outdoor project.32 A study in Singapore describes 79 primary school students who used hand-held computers to investigate how waste is produced and how best to "reduce, reuse, and recycle."33

These projects illustrate encouraging effects on learning. In the case of the environment detectives, major benefits include reduced abstraction, realistic context, and a blending of gaming and real life. The Taiwan project showed that use of the PDAs "improves student motivation and learning" as well as "positive" student feedback. Later technologies such as iPhones can easily merge external devices into one for educators conducting the same kind of learning activity. The Singaporean study showed improved understanding and better application of the 3R principles that the teachers want the students to learn. Such studies show that mobile learning works especially well for field trips outdoors primarily in K–12 settings. However, lessons and experiences from such studies can easily be transferred to the higher education environment. The improvement of context-awareness technology, for example, creates a huge potential for using mobile devices in study-abroad programs or during field trips. Students exploring a museum would find it helpful to have a handheld guide to quickly research a work of art on display.

Not all outdoor learning requires Internet access. In many cases, educators can update their content online, and students can download and study them offline. Audio or video podcasts are especially useful for this. Because podcasting entire lectures might encourage student absenteeism in classrooms, however, it is not a good idea to simply provide a mirror image of a lecture in a podcast episode. Instead, educators should find ways to create learning objects that are discreet and reusable without cannibalizing classroom experiences that contain these and many other learning objects.

Transcript: Ramon Huston, Professor of Political Science, on Using Computers Outside of Class, not During Class Time

I do not allow students during my lecture to have their computers open and to use technology. This seems to be counter-factual, since we have an open campus and a wireless campus and all the students do have computers. The reason I do not allow them, during my lectures, to use their computers is because I do not want distractions, and I want them to focus on what I am saying, and specifically because most of my classes are discussion-based, rather than straight lecture-based. I expect the students to have read the materials prior to coming to class. And by having the computers open I am afraid it would cause them to be more lax in their preparation for class time. I do, though, have high levels of computer usage outside of class. The students take all their exams on computers, and we can continue the discussion through our discussion board in Blackboard. So students are using the computers all the time, just not in the formal setting of the classroom.

Conclusion

When distraction becomes a problem, we can work on the technology, the student, the professor, or all of them. The "professor versus laptop (or other wireless access device)" issue is a false construct if we view technology-mediated learning as a social system offering many ways to alter one component and thus change the whole system. Rather than seeing distraction as a challenge, educators can see it as an opportunity to reflect upon and change the design of their entire instructional approach. Creative and innovative educators can use technology innovations to help reform teaching, similar to the way Guttenberg's press helped bring about scientific revolution and modern authorship.

- Scott W. Campbell, "Perceptions of Mobile Phones in College Classrooms: Ringing, Cheating, and Classroom Policies," Communication Education, vol. 55, no. 3 (July 2006), pp. 280–294.

- "Seeing No Progress, Some Schools Drop Laptops," New York Times, May 4, 2007; and "N.Y. District Kills Laptop Program," Education Week, vol. 26, no. 32 (2007), p. 8-8.

- Andrea L. Foster, "New Systems Keep a Close Eye on Online Students at Home," Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 54, no. 46 (July 2008), pp. A1–A8.

- A mobile survey at Oklahoma Christian University was conducted in fall 2008 as a review of the university's mobile learning program. Further discussion about the results will be published in an article Berlin Fang wrote for Open Education Research (in press). Also see Intouch, Oklahoma Christian University's portal to mobile learning.

- University of Chicago, "University of Chicago Law School Eliminates Internet Access in Some Classrooms," news release April 11, 2008.

- Jeffrey R. Young, "The Fight for Classroom Attention: Professor vs. Laptop," Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 52, no. 39 (June 2, 2006), pp. A27–A29.

- "iPhones the Latest to Join Mobile Learning Mix," University Business, vol. 11, no. 4 (April 2008), p. 21-21.

- Carrie B. Fried, "In-class Laptop Use and Its Effects on Student Learning," Computers & Education, vol. 50, no. 3 (April 2008), pp. 906–914.

- Michael J. Bugeja, "Distractions in the Wireless Classroom," Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 53, no. 21 (January 26, 2007), pp. C1–C4.

- Michael Cole and Yrjö Engeström, "A Cultural-Historical Approach to Distributed Cognition," in Distributed Cognitions, Psychological and Educational Considerations, Gavriel Salomon, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 1–46.

- Elizabeth Murphy and Maria A. Rodriguez-Manzanares, "Using Activity Theory and Its Principle of Contradictions to Guide Research in Educational Technology," Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 24, no. 4 (2008), pp. 442–457.

- Young, "The Fight for Classroom Attention."

- Bugeja, "Distractions in the Wireless Classroom."

- Roger Hiemstra and Burt Sisco, Individualizing Instruction (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1990).

- Bugeja, "Distractions in the Wireless Classroom."

- John Nworie and Noela Haughton, "Good Intentions and Unanticipated Effects: The Unintended Consequences of the Application of Technology in Teaching and Learning Environments," TechTrends, vol. 52, no. 5 (2008), pp. 52–58.

- Robert M. Gagné, The Conditions of Learning and Theory of Instruction, 4th Ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1985).

- Young, "The Fight for Classroom Attention."

- Maya T. Prabhu, "Students School Lawmakers on Tech's Value," eSchool News, March 5, 2009.

- Derek Bruff, Teaching with Classroom Response Systems: Creating Active Learning Environments (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, February 2009).

- Chen-Chung Liu, Chien-Chia Chou, Baw-Jhiune Liu, and Jui-Wen Yang, "Improving Mathematics Teaching and Learning Experiences for Hard of Hearing Students with Wireless Technology-Enhanced Classrooms," American Annals of the Deaf, vol. 151, no. 3 (Summer 2006), pp. 345–355.

- Miri Barak, Alberta Lipson, and Steven Lerman, "Wireless Laptops as Means for Promoting Active Learning in Large Lecture Halls," Journal of Research on Technology in Education, vol. 38, no. 3 (Spring 2006), pp. 245–263.

- Laura Naismith, Peter Lonsdale, Giasemi Vavoula, and Mike Sharples, "Mobile Technologies and Learning," Futurelab report, December 2004.

- Glen Stockwell, "Vocabulary on the Move: Investigating an Intelligent Mobile Phone-Based Vocabulary Tutor," Computer Assisted Language Learning, vol. 20, no. 4 (October 2007), pp. 365–383.

- Lydia Lum, A Useful Study Aid or Jazzed-Up Novelty? Some Are Calling Test-Prep Software on Cell Phones a Democratizing Equalizer, Others Say It Increases the Gap Between the Haves and the Have-Nots, Black Issues in Higher Education, vol. 22, no.2 (March 2005).

- John Traxler, "Defining, Discussing, and Evaluating Mobile Learning: The Moving Finger Writes and Having Writ…," International Review of Research in Open & Distance Learning, vol. 8, no. 2 (2007), pp. 1–12.

- Don Vanthournout and Dana Alan Koch, "Training at Your Fingertips," T+D, vol. 62, no. 9 (September 2008), pp. 52–57.

- Kristine Peters, "m-Learning: Positioning Educators for a Mobile, Connected Future," International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 8, no. 2 (2007), pp. 1–17.

- A. J. Romiszowski, Designing Instructional Systems: Decision Making in Course Planning and Curriculum Design (London/New York: Kogan Page/Nichols, 1981).

- Gloria Gery, Electronic Performance Support Systems: How and Why to Remake the Workplace Through the Strategic Application of Technology, First Ed. (Boston: Weingarten Publications, 1991).

- Ann Jones and Kim Issroff, "Motivation and Mobile Devices: Exploring the Role of Appropriation and Coping Strategies," ALT-J: Research in Learning Technology, vol. 15, no. 3 (September 2007), pp. 247–258.

- Tan-Hsu Tan, Tsung-Yu Liu, and Chi-Cheng Chang, "Development and Evaluation of an RFID-Based Ubiquitous Learning Environment for Outdoor Learning," Interactive Learning Environments, vol. 15, no. 3 (December 2007), pp. 253–269.

- Wenli Chen, Nicholas Yew Lee Tan, Chee-Kit Looi, Baohui Zhang, and Peter Sen Kee Seow, "Handheld Computers as Cognitive Tools: Technology-Enhanced Environmental Learning," Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, vol. 3, no. 3 (November 2008), pp. 231–252.

© 2009 Berlin Fang. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.