Whereas institutions in the spring had little time to react to a sudden and unprecedented crisis, many institutions this fall are benefiting from more time, more support, and better preparation for online modes of course delivery and instruction.

As the COVID-19 pandemic upends higher education in 2020, institutions are relying on digital alternatives to missions, activities, and operations. Challenges abound. EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.1

The Challenge

Through the seismic disruptions to higher education wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed the Herculean efforts of institutional staff, faculty, and leadership to keep their communities safe while continuing to provide quality learning experiences and vital services. At the same time, we have also become acutely aware of the ways in which institutions were ill equipped to meet the demands of such an unprecedented crisis and such a sweeping migration of services and courses to online modes of delivery.2 Now, with more time and experience under their belts, and after much-needed planning and preparation over the summer months, are institutions ready to meet the demands of a new academic year? Do the hard-earned lessons of the spring and preparations of the summer hold promise for a less turbulent term this fall? And what challenges remain for institutions on the road ahead?3

The Bottom Line

Glimmers of hope are on the horizon as institutions journey into the fall term. Summer planning and preparation, particularly in the areas of online course design and instructional support, have resulted in a renewed optimism among respondents that their institutions and faculty are much improved in their online capabilities and far more prepared to meet the challenges of the new academic year. Though this is certainly an occasion to acknowledge and celebrate improvements, challenges still lie ahead in the areas of connectivity and longer-term institutional investments and sustainability for new models and practices.

The Data: Better Laid Plans for the Fall

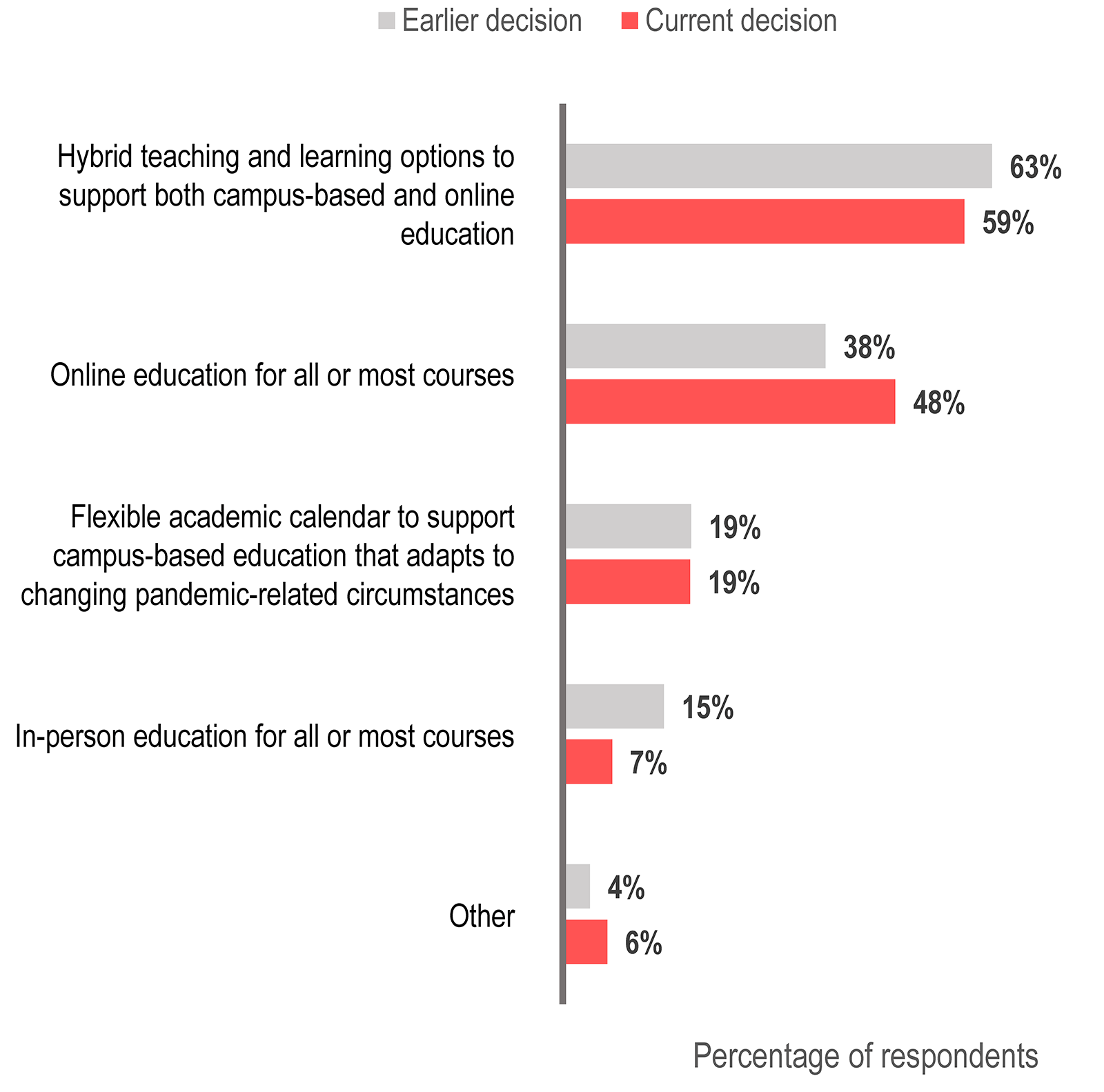

Fall decisions are holding steady, with more going online. What are institutions' most up-to-date plans for fall operations, and how do those plans compare with plans laid out earlier in the year? According to our survey respondents, institutions' current operations by and large resemble and strongly correlate with "official" operating decisions that were made earlier in the summer, with a few notable variations (see figure 1). A majority of respondents (59%) indicated that their institution is currently offering hybrid teaching and learning options, slightly lower than the 63% of institutions that had previously made official decisions to offer hybrid options. Notably, a larger proportion of respondents reported that their institution is currently offering online education for all or most courses (48%) than earlier official decisions (38%). Substantially fewer respondents reported that their institution is currently offering in-person education for all or most courses (7%) than earlier official decisions in this area (15%).

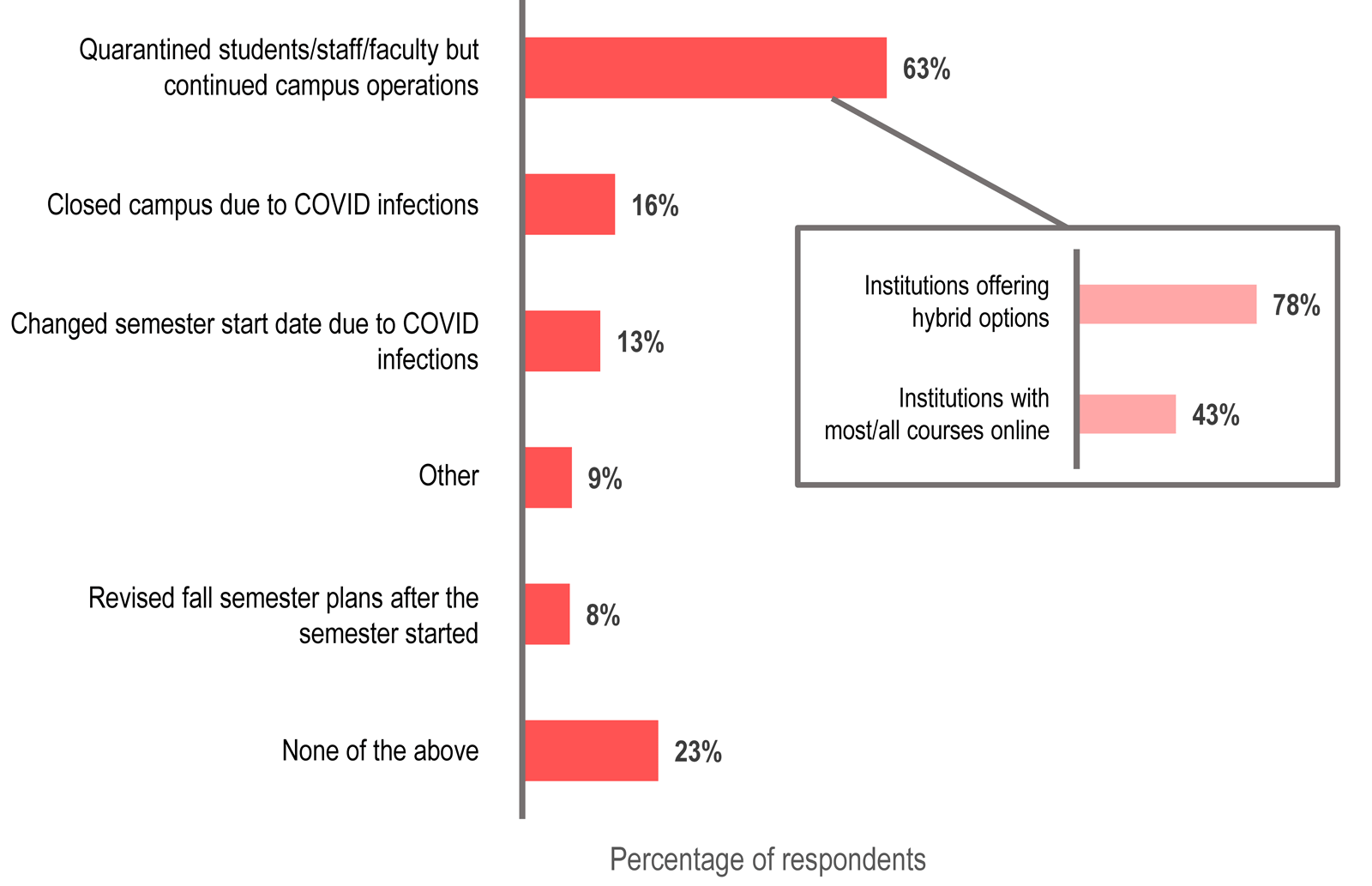

Institutions are making few changes as the term begins, and even fewer for campuses operating online. While institutions' official operating decisions for the fall have largely remained stable since the start of the term, some of these decisions may already be necessitating additional adjustments as institutions respond to the ever-evolving pandemic. Though few respondents indicated that their institution has taken measures such as closing the campus or changing the academic timeline due to COVID-19 infections (see figure 2), a strong majority reported that their institution has imposed quarantines for students, staff, or faculty while continuing to maintain campus operations. Importantly, the institution's operating model might be a factor in these experiences—respondents whose institution is currently offering online education for all or most courses were far less likely to report quarantine experiences than respondents whose institution is currently offering hybrid education. Respondents from "online education institutions" were also far more likely than respondents at "hybrid education institutions" to report that they had experienced none of the COVID-related events we asked about—37% compared to 15%, respectively.

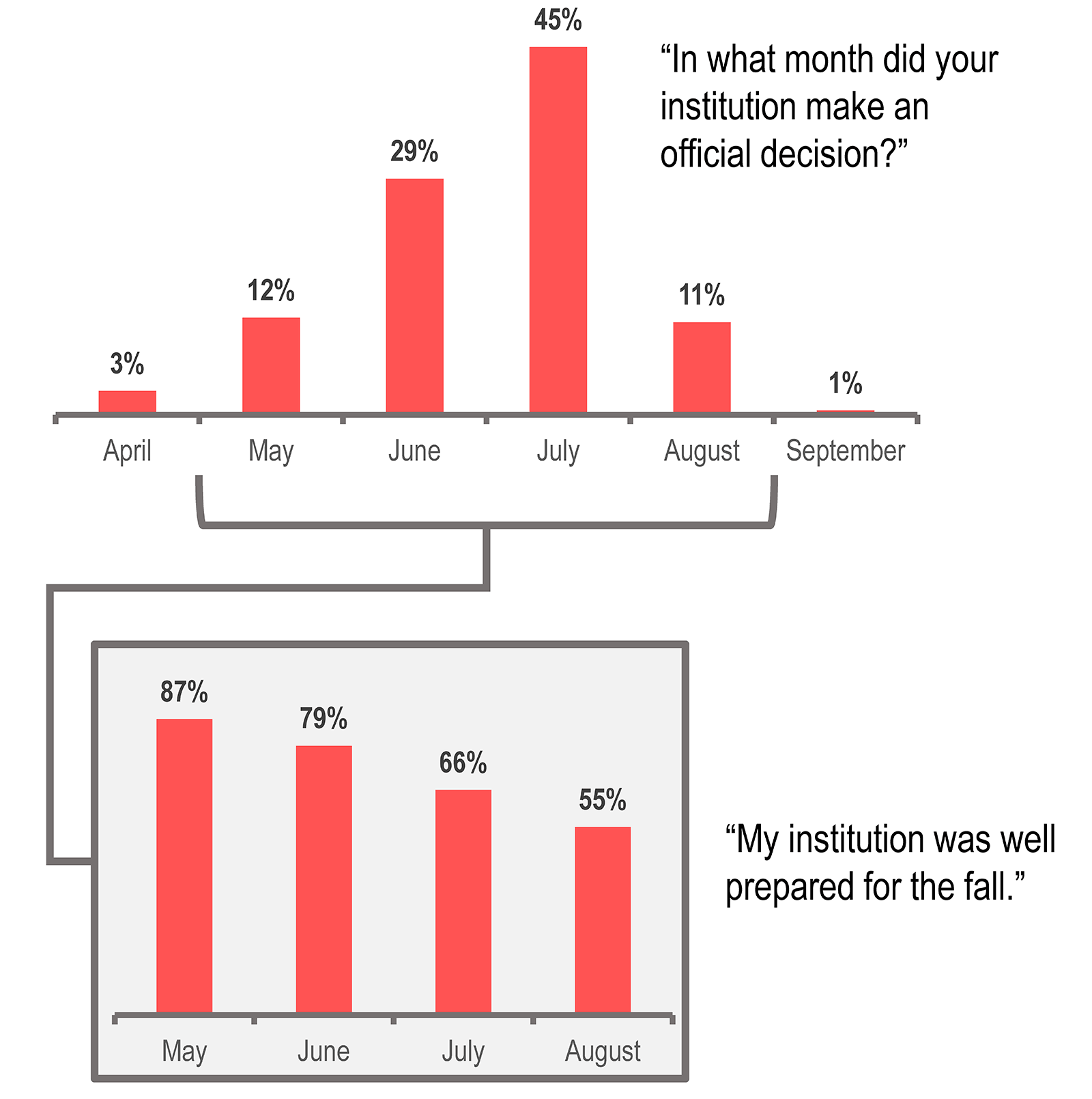

Make plans, and make them early. Just as important as the "what" of institutions' operating decisions, the "when" of those decisions may have important implications for planning, preparations, and readiness headed into the fall term. When asked to specify the month in which their institution had reached an "official" operating decision for the fall, a plurality (45%) of respondents reported that their institution's decision had been made in the month of July (see figure 3). Less than a third of respondents reported that their institution's decision had been made in June, and the bulk of the remaining respondents indicated that their institution had made a decision in either May or August.

We might speculate that those institutions making fall operating decisions earlier in the summer would have benefitted from more time to plan and prepare and would therefore feel more ready for the fall term compared with institutions making decisions later. And indeed, results from our survey validate these assumptions, as we see considerably higher levels of agreement among respondents from "earlier-decision institutions" that their institution was well prepared for the fall term compared with respondents from "later-decision institutions." As one of our survey respondents concluded, "Time is what made the difference."

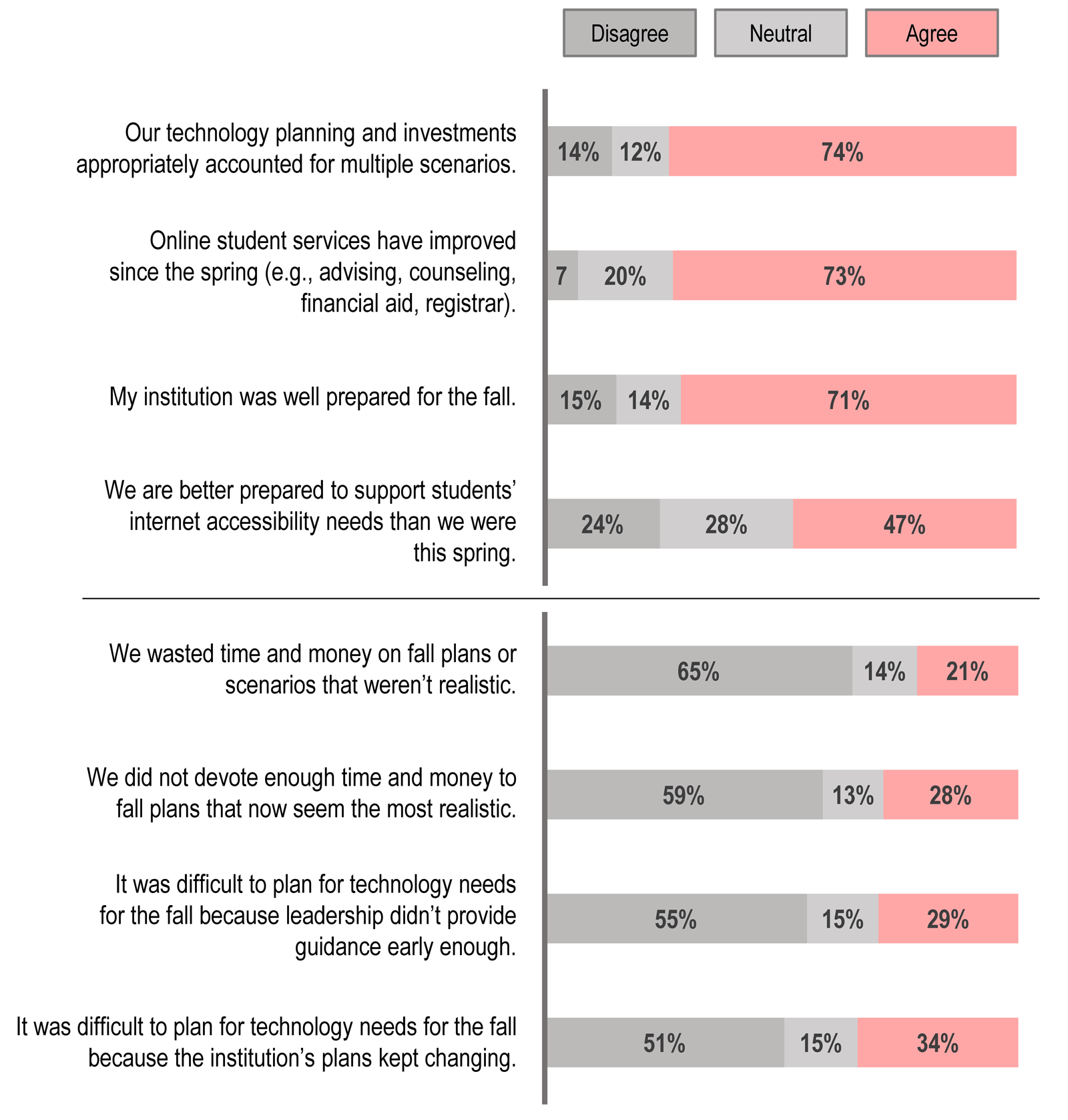

Things are looking up. Your Wi-Fi signal? Maybe not. Overall, respondent attitudes about the planning work their institution had done over the summer, as well as their institution's preparedness for the fall relative to this past spring, were very positive (see figure 4). Strong majorities of respondents agreed that their planning had appropriately accounted for multiple fall scenarios, that their student services had improved since the spring term, and that their institution was well prepared for the fall. Few respondents agreed that their fall planning activities had been wasted, misguided, or difficult. The single blemish on an otherwise positive fall planning experience: less than half of respondents agreed that they are better prepared to support student internet access now than they were in the spring.

The Data: Closing the Gap in Online Quality

Summer planning focused on better instructional support. As most institutions scrambled to migrate courses to online modes of delivery in the spring, early reflections from the field lamented that there was still much work to be done in terms of faculty development and online course and instructional design.4 The "remote learning" our students were experiencing on the fly was a far cry from the higher-quality "online learning" they might be able to experience with more time, planning, and support.

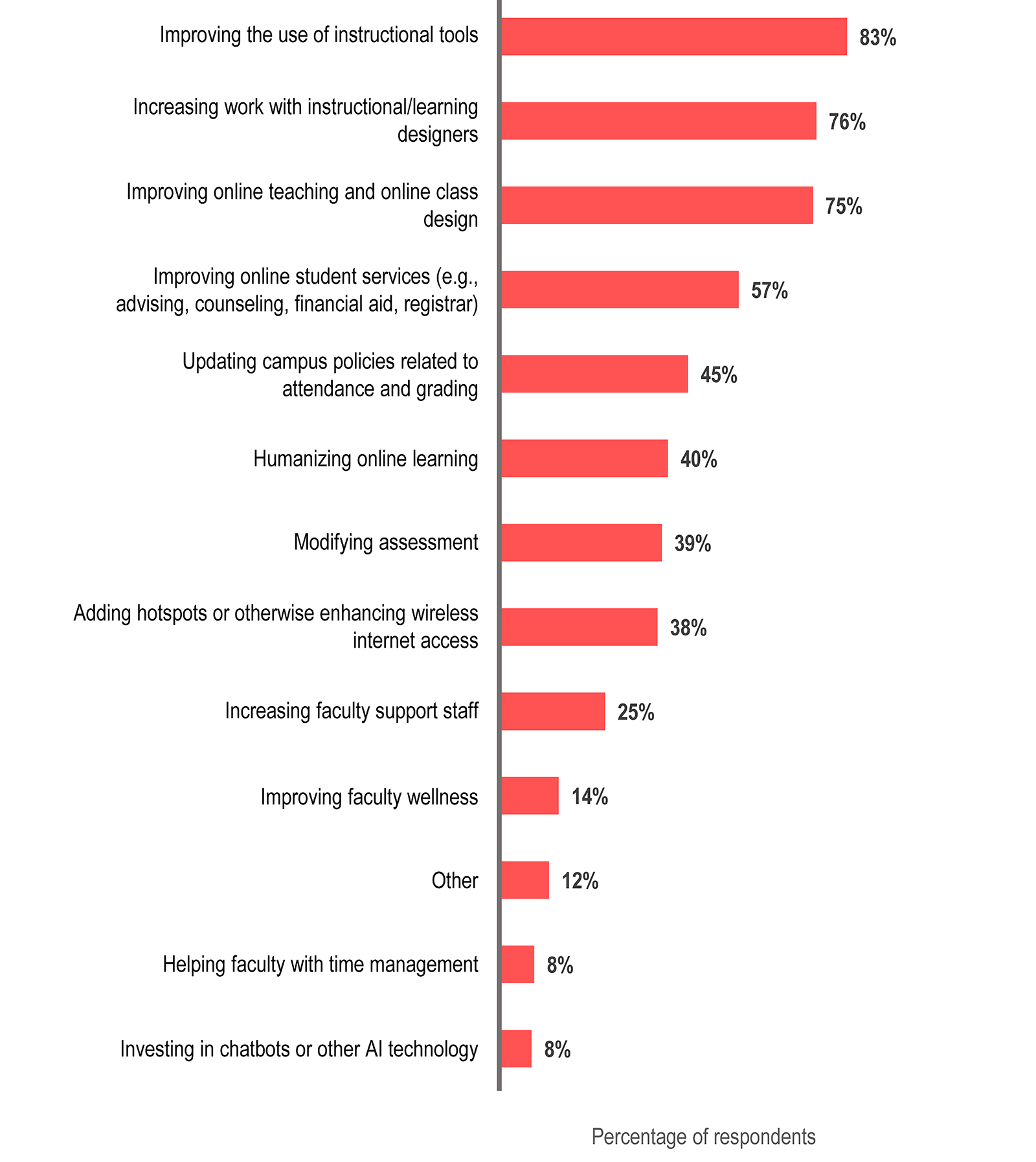

Findings from our survey suggest that many institutions devoted their summer months to closing that gap between "remote" and "online" learning, with their summer planning and preparations focused squarely on online and instructional improvements (see figure 5). Asked how their institution had used the summer to prepare for the fall term, a full 83% of respondents reported that they had used the summer to improve the use of instructional tools, and another three-quarters reported that they had focused on increasing work with instructional/learning designers and on improving online teaching and class design. As was noted above regarding internet access, only 38% of respondents reported that their institution had focused their summer on adding hotspots or otherwise improving internet access.

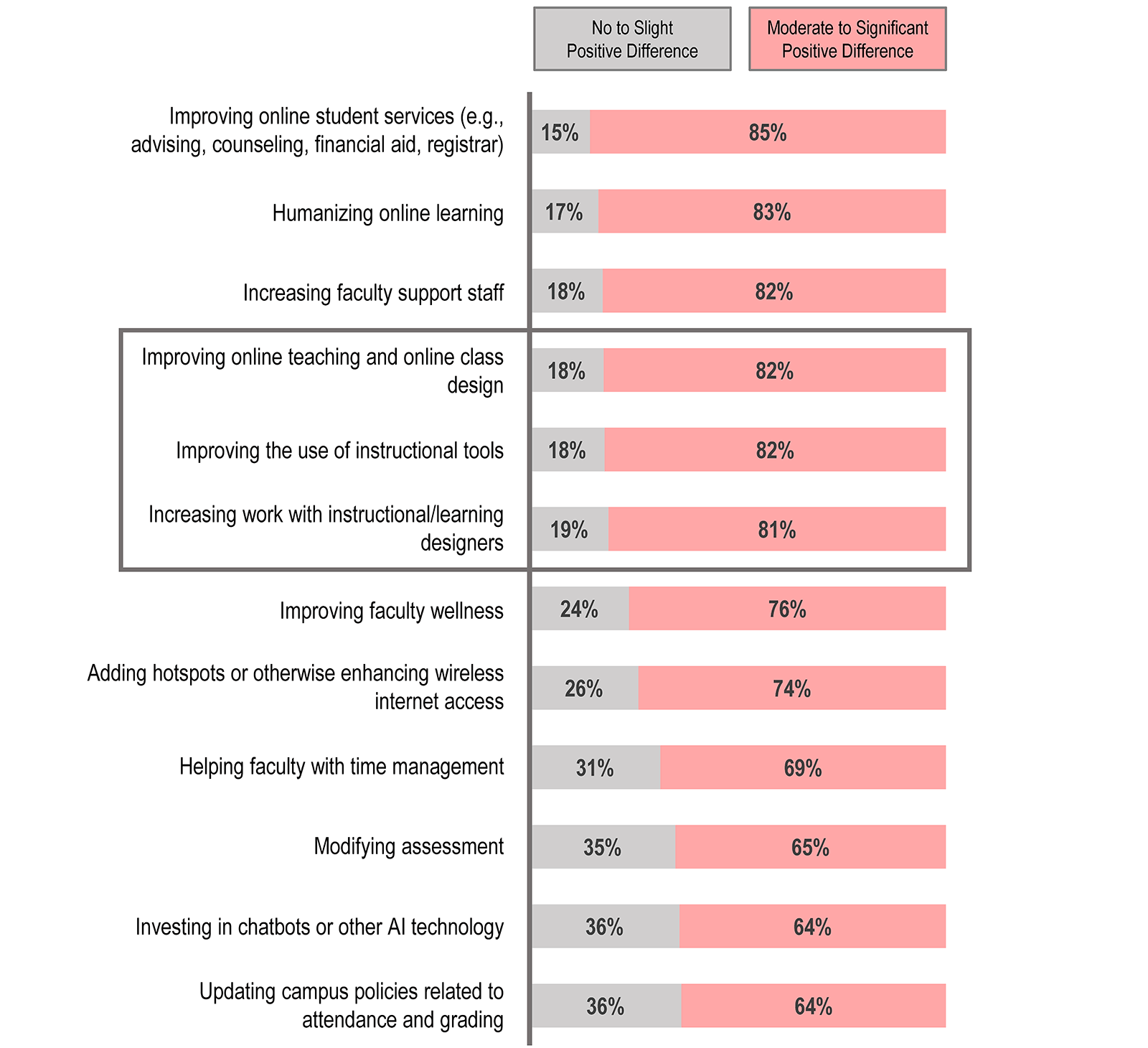

Summer investments are yielding positive results. When asked in a follow-up question to rate the positive difference their summer planning and preparation activities had made toward having a successful fall term, respondents indicated that their summer activities generally were making a moderate to significant positive difference so far. It seems any amount of additional planning and preparation across all of the areas we asked about is proving helpful, including the online- and instructional-focused investments the vast majority of institutions had made over the summer (see figure 6, highlighted).

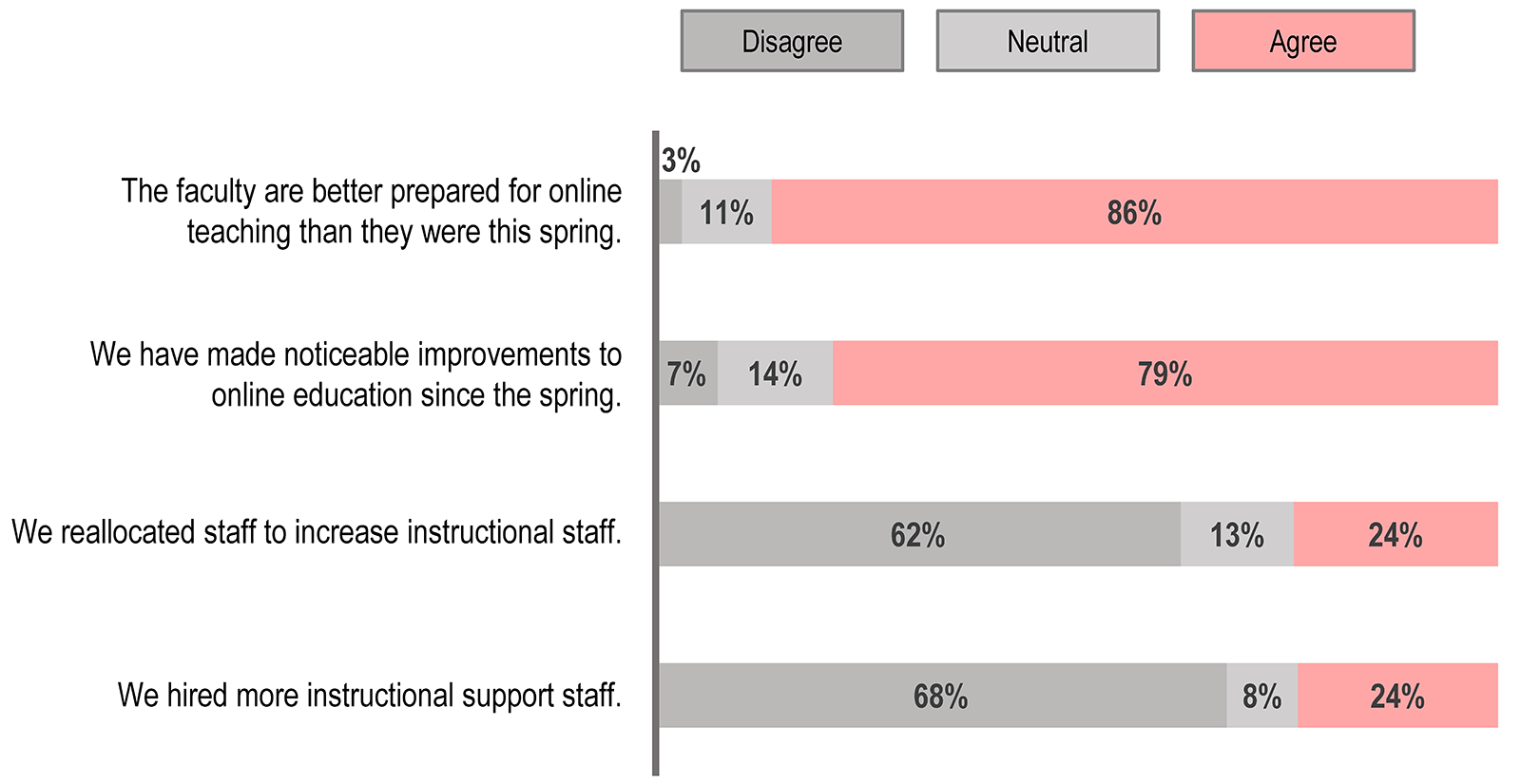

We've got to admit it's getting better…for now. Most of our respondents agreed that their faculty are now more prepared for online teaching than they were in the spring and that online education at their institution has noticably improved (see figure 7). Of course, it remains to be seen (and cannot be determined through these data) whether these perceived improvements translate into improved experiences and learning for students themselves or into improved long-term institutional outcomes. Of possible concern for the long-term sustainability and outcomes of these institutional efforts, only about a quarter of respondents agreed that their institution had made resource investments in the form of reallocated or new instructional staff. This may be unsurprising and understandable, given many institutions' present financial and staffing constraints, but institutions with long-term designs for online education should consider whether and how they might begin to invest more in such staffing changes in the future.

Common Challenges

Internet connectivity. Though our findings indicate that institutions are much more prepared this fall than they were in the spring and that improvements—particularly in areas of online learning and instructional support—should contribute to a more successful term this fall, it's clear that institutions could devote more attention and investment to improving student and faculty internet access. Only a third of respondents indicated that their institution had focused on this issue over the summer months, and less than half of respondents felt that their institution was better prepared to support student internet access now than in the spring. A sampling of respondent comments help bring this issue into relief:

- "Our students are not equipped with technology or internet to successfully complete an online course in many cases, unless computer stations are available at the college or elsewhere."

- "Faculty were not prepared with the right equipment or internet bandwidth at home."

- "Our students do not have technology or internet at home."

Long-term support. Although respondents to this and other recent QuickPoll surveys have noted the promising trend of increased engagement from faculty interested in learning to use new tools and course-delivery modalities, longer-term and sustainable advancements in these areas will require substantial investments on the part of the institution. In particular, we know that reskilling and expanding the institution's workforce is a critical component to digital transformation at the institution,5 and yet few respondents in this survey reported that their institution had been increasing or reallocating staff to support the demand for online learning and instructional improvements.

Faculty buy-in. Even with impressive improvements to course and instructional design and the increased use of instructional tools, it's clear from respondent comments that some faculty still have a long way to go toward adapting to online education and that some still require coaxing to learn new tools and rethink how they approach their work. Some respondents expressed surprise in discovering just how little their faculty knew or cared about online instruction, and other respondents opined that instructional training for faculty should be more consistently and systematically implemented. Again, a sampling of respondent comments helps illustrate this feedback:

- "We learned faculty need to be trained how to teach online and that they require monetary incentive to get the training they need."

- "Faculty need much more training for this type of environment, and administration cannot expect improvements when no resources are added for training and support."

- "[We learned that] most faculty are not prepared to pivot to online courses and they don't care to make the change, so they either retire early or wait out the pandemic."

Promising Practices

Early and flexible planning. We've seen through this survey that the luxury of more time can lead to perceived benefits in planning and improvements in practice. Though "plan early" is certainly a common refrain among our respondents in their open-ended comments, many respondents also recognize that early planning alone won't be enough. Plans change, especially under pandemic conditions, and so respondents also recommended flexibility in planning and an anticipation and openness to alternative or new plans when old plans fail or are no longer relevant. As one respondent put it, "Plan, but understand that there is no playbook, and be willing to change those plans quickly."

Focus on improving courses and instruction. Technology can help solve any number of problems at the institution, and it can be the conduit through which meaningful transformation and experiences in the classroom take place. And now is certainly the moment many technology leaders should seize to get buy-in from their faculty and staff on adopting needed solutions. But without a focus first and foremost on course design and pedagogy, the best technology solutions we can put in place ultimately will not be enough. To quote one of our respondents, "First pedagogy, technology second."

As a place to begin, EDUCAUSE offers a resource hub focused on the topic of instructional design, and our ID2ID and Instructional Design Community Group programs may offer helpful opportunities for direct peer-based learning and sharing.

Practice empathy and patience. Finally, while institutions may be more prepared and more successful this fall than they were in the spring, the COVID-19 pandemic is still with us for the foreseeable future, and many of us feel no less adrift and anxious than we did earlier in the year. Comments reveal a sober awareness that respondents are still in need of empathy, patience, and kindness and that institutions' faculty, staff, and students need the same as well. Even as we continue improving in our instructional practices and supports, and even as we roll up our sleeves and dive into the hard and exciting work still ahead this fall, we are still people first and foremost, and we are people living through unprecedented times.

As one of our respondents counseled, "Keep your spirits up. Don't burn people out. Be kind with yourselves and others." As perhaps our highest measures of success this fall, may we all incorporate these goals into our fall planning as well and support one another in these ways on the road ahead as we strive to do our best work together.

EDUCAUSE will continue to monitor higher education and technology related issues during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. For additional resources, please visit the EDUCAUSE COVID-19 web page. All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page.

For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog, as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions. ↩

- Mark McCormack, "EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Fall Planning for Online and Physical Spaces," EDUCAUSE Review, August 7, 2020. ↩

- The poll was conducted on September 15, 2020, consisted of 11 questions, and resulted in 487 complete responses and 70 partial responses. Poll invitations were sent to participants in EDUCAUSE community groups focused on IT leadership and instructional technology. Most respondents (475) represented US institutions. Respondents from Canada, Asia, and the UK also participated. Institutions of an appropriately diverse and well-balanced range of sizes and Carnegie Classifications participated. ↩

- Ryan Craig, "What Students Are Doing Is Remote Learning, Not Online Learning. There's a Difference," EdSurge, April 2, 2020. ↩

- Malcolm Brown, Betsy Reinitz and Karen Wetzel, "Digital Transformation Signals: Is Your Institution on the Journey?" EDUCAUSE Review, May 12, 2020. ↩

Mark McCormack is Senior Director of Analytics & Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2020 Mark McCormack. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.