Orientation experiences support students’ transition to the first year of college, which is essential for student success. This applies equally to online learning.

Overview and Key Considerations

By Jaimie Hoffman

Whether enrolling in a single online class or a fully virtual program, students need to be prepared for the academic and social learning that compose their educational journey. While some may arrive with years of online learning experience, others will require familiarization with processes, tools, expectations, and the campus community—and all will benefit from an introduction to their new academic community. Orientation experiences support students' transition to the first year of college, which is essential for student success.1 This support is particularly important for those students from historically marginalized populations.2

Orientation for online learners should be holistic and would ideally mirror content delivered in the onsite orientation experience, since students enrolling in online courses may come to campus infrequently or possibly not at all. Student orientation helps to foster student success; research suggests that those who participate in orientation programs generally perform better than those who do not and persist to graduation at a higher rate.3

Educators seeking to create a strong online orientation may grapple with similar questions:

- How can we orient students to online learning?

- What should be included in the orientation, and how should it be delivered?

- How can we encourage students to complete the experience?

- How will we know if the orientation was successful?

There are three key areas that should be considered when creating an orientation for online learners: (1) orientation learning goals and content; (2) course design features and approach; and (3) assessment and student completion requirements.

Consideration #1: Orientation Learning Goals and Content

As in any other learning experience, educators should first identify the desired learning outcomes of the student orientation. Leveraging existing onsite orientation outcomes and schedules is important to ensure that students are integrated holistically into the academic community.

Creation of the student orientation would ideally be a campus-wide collaboration to leverage expertise across divisions. The inclusion of videos from campus leaders also symbolizes commitment to all students, including those studying online. Further, leveraging the campus community to identify intended outcomes of the student orientation might uncover content areas that otherwise would not have been identified if the program was owned by only one area.

Generally speaking, the orientation should

- boost students' confidence for success online,

- foster a sense of community among students, faculty, and staff,

- equip students with the tools necessary to be positive community members,

- facilitate academic preparedness and skill-building (e.g., time management),

- provide support and engagement resources, and

- give students the opportunity to use the technology they will encounter in their courses.

Consideration #2: Course Design Features and Approach

Stakeholders involved in the initiative should consider multiple factors that drive course location, design features, and approach.

Course location: Since online students will complete coursework on a campus learning management system (LMS), or virtual campus, creating a student orientation course within the same virtual space fosters a seamless experience for students. For example, students cannot actually use the tools (e.g., discussion boards, engagement tools, gradebook, assignment submission) they will use in their courses if the course is located outside of the LMS.

Modality: Thinking through the orientation modality is important for the student experience. Desired outcomes and the modality of the students' curricular environment should drive the modality of the orientation. For instance, if students never have to meet synchronously for their online courses, a blended or hybrid orientation may not be effective. Alternatively, there may be a specific community-building activity that would be ideal in a synchronous session; thus, employing a series of live orientation sessions via video might be best. The course learning outcomes can also help inform what topics should be reinforced in live sessions.

Interactive Learning Objects (ILOs): Campus leaders should think through how content will be delivered in order to achieve course objectives and consider Universal Design for Learning principles. A course will not be engaging if every page involves large paragraphs of text, for example, and it is unlikely that students will retain much of the information. ILOs can foster deeper learning. For instance, employing an ILO where students have to respond to academic integrity scenarios will enable them to relate to the material better than if they simply read an informational page about academic integrity.

Facilitated vs. fully self-directed: Learning outcomes and staffing resources will likely dictate whether or not the student orientation course will be facilitated or fully self-directed. Ideally, a faculty or staff member would be able to log into discussions or ILOs to offer commentary on students' work, although this may not be sustainable.

Perpetual or created new each term: When the student orientation is created in the LMS, campus leaders will need to consider whether the course will be open perpetually or if it will be prepared anew for every forthcoming term. It is certainly less work to have a single course to which students are continually added, but this does mean that new students will see posts submitted by past students, and in some cases, past students will be able to return and engage with newer students. This could be leveraged for mentoring, but it also might be seen by students as a "canned" course versus a more customized experience created for each new cohort. While it is possible to restrict the time during which students can access the course so that they can't engage with newer students, this also means they can no longer access the content as they need it.

Consideration #3: Assessment and Student Completion Requirements

Any meaningful learning experience will end with assessing the student experience. Therefore, stakeholders should consider using the framework developed by Donald L. Kirkpatrick and James D. Kirkpatrick.4 They outlined four levels of evaluation: how students felt about the experience; what students learned through the course (e.g., assessing the achievement of the stated learning outcomes); how the student orientation actually impacted the students' experience once courses began; and finally, how the student orientation affected overall student success. This approach to assessing the student experience through online orientation should then be counterbalanced with how the onsite orientation is assessed (with consideration toward creating an equitable experience).

At a minimum, most campuses require attendance at the onsite orientation; therefore, some confirmation of completion is likely needed for this course. To confirm completion, campuses can leverage digital strategies such as having students upload a confirmation page as an assignment in the course (that way, students experience the process of submitting an assignment, much as they would in an online course) or creating a digital badge in the LMS.

Orienting Students to Online Learning at CSU Channel Islands

By Megan Eberhardt-Alstot, Jill Leafstedt, and Jaimie Hoffman

To illustrate these concepts, here we provide an overview of how one institution approached the creation of an orientation for online learners, along with some data on the use and impact of the course. Jill Leafstedt, associate vice provost for innovation and faculty development at CSU Channel Islands (CI), established the vision for the course; Jaimie Hoffman, an independent consultant, designed the initial version of "Learning Online 101"; and Megan Eberhardt-Alstot, learning designer at CI, lead the subsequent revisions and implementation.

CSU Channel Islands (CI) is located in Camarillo, California, and is one of 23 campuses in the California State University System. CI is a mid-sized institution with around 8,000 students, of which 97 percent are undergraduates. In 2010, CI achieved the Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) status, and today 51.6 percent of students are Hispanic/Latino, and 58 percent are first-generation college students. As with the national trend, a growing percentage of courses (12%) are offered online. Leafstedt identified the need to develop a resource that could support students "learning how to learn" online and reduce the time that faculty spend providing technical assistance in online courses. Key decisions were made regarding the three areas, noted above, that should be considered when creating an orientation for online learners.

Orientation Learning Goals and Content

The primary course goal was to teach students how to become successful online learners. More specifically, we hoped to boost students' confidence in learning online, equip students with the tools necessary to be positive community members, and give students the opportunity to use the technology they would encounter in their courses. While we wanted to facilitate academic preparedness by building skills such as time management, motivation, and reading basis, we also sought to keep the course completion time to under two hours. Five modules make up Learning Online 101:

- Welcome and Start Here. We begin with a welcome from the university president and provide an overview of what students can expect in the course

- Starting with a Positive Mindset and Reflecting on Your Readiness. This module covers ideas like motivation, growth mindset, and myths of online education. It also includes a readiness assessment so that students can determine what areas they might need to improve upon in order to be successful in learning online.

- Navigating the Online Classroom. This module is designed to help students understand the ins-and-outs of using CI Learn (Canvas) and build basic competency in the digital tools (e.g., Google Apps for Education Suite and Zoom) that will most likely support their academic work and collaboration within a digital learning environment. Intentional consideration led to a focus on teaching tools that were both freely accessible to all students via their campus accounts and completely accessible via PC or mobile device.

- Establishing a Foundation for Academic Success. This module reviews several time-management tips, the importance of study groups, and other useful suggestions specific to online and blended courses. Also featured in this module is a close look at how to practice "netiquette" (Internet etiquette).

- Understanding Your Support System. This module reviews one of the most underutilized learning skills: knowing when and where to ask for help. In this module, students are introduced to support systems available for them throughout their time at CI.

To humanize the experience, narratives from faculty, current online students, and key staff members and administrators are woven throughout Learning Online 101. The video example below captures a faculty member providing tips for success in online and blended courses.

Course Design Features and Approach

With the content established, we then tackled the discussion of course location, design features, and other facilitation approaches.

Course Location: We decided to create the orientation course in the LMS because we wanted students to work in the same space, and with the same tools, that they would be using for their online and blended courses. We also wanted to leverage digital badges to certify completion of the course.

Modality: Currently the course is entirely asynchronous, enabling students to complete the course pm their own time. Further, we sought to make the experience as easy to complete and as accessible as possible, a key factor that has led to a high level of adoption by CI faculty.

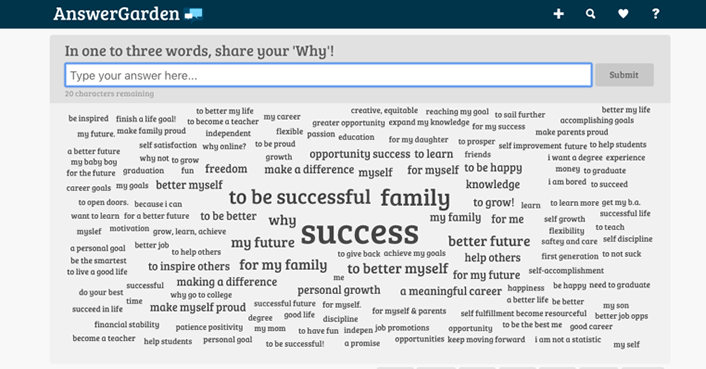

Interactive Learning Objects (ILOs): In addition to videos that prompted students to reflect, the course provided a variety of ILOs to foster deeper engagement with content. For instance, students are prompted to take a readiness assessment for online learning to consider the areas in which they should focus during the course, and they are offered some specific exercises to build relevant skills. After learning about the "Start with Why" concept from Simon Sinek,5 students are encouraged to share their "why" via the Answer Garden tool, as pictured below. Finally, for the purpose of awarding digital badges, students have to earn a passing score on a knowledge check at the end of each module.

Facilitated vs. fully self-directed: This course is entirely self-directed but is monitored by Eberhardt-Alstot, who also serves as the point of contact for student support. In the "Welcome and Start Here" module, her photo and personal welcome message present an approachable human connection if students encounter any technical issues or have questions. The goal here is a positive introduction to online learning; therefore, it is essential that students receive a timely, humanized response from an empathetic voice. After all, successful completion of the course is part of building students' self-efficacy for online learning. Before the start of each term, Eberhardt-Alstot reviews both student and faculty feedback and updates content accordingly. ILOs are checked periodically throughout the term. We have a vision for more facilitated engagement, but we need the personnel to support the vision. To date, although we have awarded badges to over 800 students, fewer than ten students have sent requests for support.

Faculty Support: In addition to student success, this course responded to online faculty members' concerns about their preparedness to field students' technical needs. We intentionally developed a dissemination process that required minimal faculty time and technical knowledge. Students use the Canvas self-enroll feature to join Learning Online 101. We created an assignment that included the self-enroll link and directions with screenshots on how to locate and submit the completion badge. By placing the assignment in Canvas Commons, faculty can import the assignment into their course and assign it to students, requiring ten minutes or less of faculty time. A rationale, course preview, and directions for faculty on how to integrate the course are available on our faculty support website.

Assessment and Student Completion Requirements

While Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick suggest four levels of evaluation, we found it practical to include only two levels of assessment in Learning Online 101: what students learned through the course, and how they felt about the course.

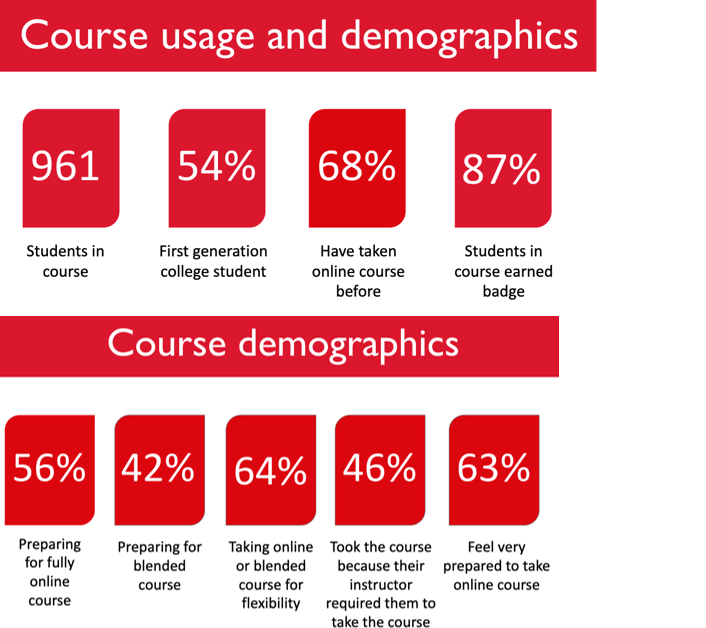

General data and demographics: As of fall 2019, 961 students had logged into the course, while 892 continued past the first knowledge check. Of those students, a majority who completed the course evaluation were first-generation college students and had taken an online course before. Students' primary purpose for taking the course was to prepare for a fully online course; almost half (46%) took the course because they were actually enrolled in an online course. In addition, 87 percent of the students completed the steps necessary to earn a digital badge.

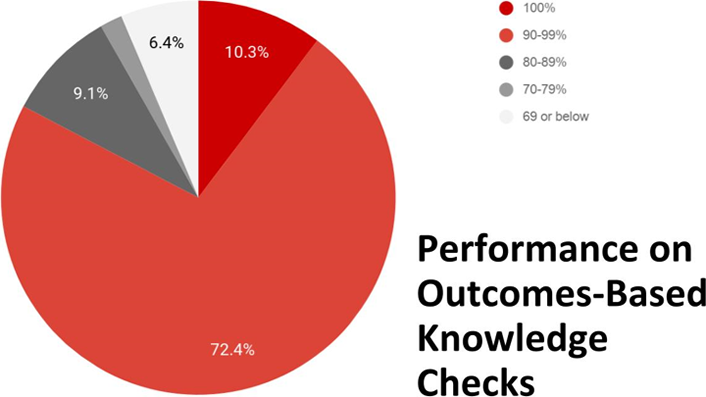

Learning outcomes: We sought to understand what students learned by examining performance on knowledge checks. According to completion of the knowledge checks, 92 percent of students earned a score of 80% or better.

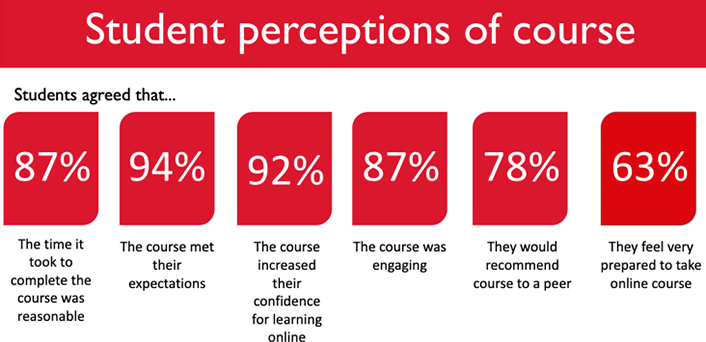

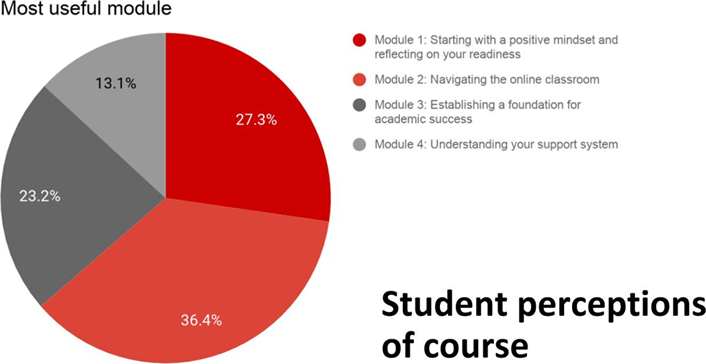

Students' perceptions of the course: On the whole, students expressed positive feedback. A majority said that they felt prepared to take an online class, that the time it took to complete the course was reasonable, that the course met their expectations, and that the course increased their confidence for learning online. Furthermore, they indicated that the course was engaging, and they reported that they would likely recommend it to a peer. The second module, "Navigating the Online Classroom," was students' preferred module.

Students also offered words of appreciation for the experience. Below are two quotes from their feedback:

In this course, I thought that they were just going to talk about how critical it is that we manage our time when it comes to online courses, but I was really surprised and thankful that they give tools for people who might be nervous before starting the online class. The fact that even the first module talks about covering concepts like motivation, growth mindset, and myths of online education is amazing and very encouraging! To me this tells me that our school cares about our mental state of mind but also they care about our growth since the first module gives us tools to figure out what areas could be improved in order to succeed in our online class.

It was extremely helpful! I had never heard of/noticed Zoom before this!!! Also I liked being asked to consider WHY I am trying to achieve my goals. Very inspirational to be reminded of that personal perspective. The quizzes were a fair challenge, definitely had to go back and re-read a few bits I had missed. Not too easy so wasn't boring. :)

Future assessment plans: We have plans to add a third evaluation level, juxtaposing performance data from those who took online courses and successfully completed Learning Online 101 with data from those who did not. Also, we would like to follow up with the students who did not persist in the course after the first knowledge check.

Student completion requirement and incentives: Faculty were invited to use Learning Online 101 to prepare students for success in their blended or online courses. Some faculty strongly recommended completion, while others offered credit or extra credit. We used Badgr (which has a free integration with Canvas) to provide a digital badge when students successfully completed the knowledge checks and end-of-course evaluation.

Conclusion

Whether you are creating an orientation course for students who are completing fully online degrees or one for students who are new to the process of learning online, developing the course in a planned, purposeful manner is key. The course should "begin with the end in mind": you should clearly define goals around what you want students to know or be able to do at the end of the experience. And as with any initiative, assessment will allow you to discover ways in which the course design features and approach may be adjusted to foster continual improvement. A well-planned online orientation is essential for student success ahead.

For more insights about advancing teaching and learning through IT innovation, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Transforming Higher Ed blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative and Student Success web pages.

Notes

- Debra A. G. Robinson, Carl F. Burns, and Kevin F. Gaw, "Orientation Programs: A Foundation for Student Learning and Success," New Directions for Student Services, no. 75 (Fall 1996); Thomas Hollins, "Examining the Impact of a Comprehensive Approach to Student Orientation," Inquiry: The Journal of the Virginia Community Colleges 14, no. 1 (2009). ↩

- Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini, How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research, vol. 2 (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005). ↩

- Ralph R. Busby, Hollie L. Gammel, and Nancy K. Jeffcoat, "Grades, Graduation, and Orientation: A Longitudinal Study of How New Student Programs Relate to Grade Point Average and Graduation," Journal of College Orientation and Transition 10, no. 1 (Fall 2002); Charles A. Boudreau, and Jeffrey D. Kromrey, "A Longitudinal Study of the Retention and Academic Performance of Participants in Freshmen Orientation Course," Journal of College Student Development 35, no. 6 (November 1994). ↩

- Donald L. Kirkpatrick and James D. Kirkpatrick, Evaluating Training Programs (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2005). ↩

- Simon Sinek, Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action (New York: Portfolio, 2009). ↩

Jaimie Hoffman is Vice President for Student Affairs and Learning at Noodle Partners.

Megan Eberhardt-Alstot is Learning Designer at California State University, Channel Islands.

Jill Leafstedt is Associate Vice Provost for Innovation and Faculty Development at California State University, Channel Islands.

© 2020 Jaimie Hoffman, Megan Eberhardt-Alstot, and Jill Leafstedt. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.