Key Takeaways

- In the face of constant calls for innovation from within and outside the university, why does it seem so difficult to liberate creativity among the higher education community?

- A strong culture of risk management, traditional design processes, high compliance burdens, and measuring return on investment created organizational gridlock at the University of Southern Queensland.

- Recognizing that many instructors wanted to simply demonstrate an idea, the newly created Technology Demonstrator team reduced the costs of small-scale creativity and innovation, while also managing organizational needs for compliance and resource management.

- The Technology Demonstrator program built, nurtured, talked about, and managed the Technology Demonstrators ethos to assist in growing the university's culture of exploring innovation and also to grow capacity and capability across campus.

Why does it seem so difficult to liberate creativity throughout the university community? After all, higher education institutions include intelligent, creative, and dedicated professors; talented professional staff; enthusiastic, or at least discriminating, students; and one of the most important missions in contemporary society. In addition, constant calls for innovation come from within and outside the university. The NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Higher Education Edition,1 for example, continues to mention "Advancing Cultures of Innovation" as a key trend toward accelerating creative and innovative technology adoption in higher education. Despite strong winds, however, our large sailing ships take time to turn in new directions.

At the University of Southern Queensland (USQ), we found that a strong culture of risk management, traditional design processes, high compliance burdens, and measuring return on investment created organizational gridlock. Experimentation, although desired, looked organizationally costly for teaching as well as professional staff. This left our university with an innovation paradox: the need to be flexible and agile while also assuring, as best as possible, the appearance of a stable and reliable core. Geoff Sharrock recently reemphasized this paradox, noting risk aversion and the tension between balancing agility and stability.2 This appears as a pervasive challenge among 21st century universities and many other large organizations. As Wouter Aghina, Aaron De Smet, and Kirsten Weerda pointed out, higher education needs to master this paradox:

In our experience, truly agile organisations, paradoxically, learn to be both stable (resilient, reliable, and efficient) and dynamic (fast, nimble, and adaptive). To master this paradox, companies must design structures, governance arrangements, and processes with a relatively unchanging set of core elements — a fixed backbone. At the same time, they must also create looser, more dynamic elements that can be adapted quickly to new challenges and opportunities.3

To address the innovation paradox in our context at USQ, we had to acknowledge that the simple economics at work significantly hindered developing a culture of innovation. Time-poor academic staff found the time and frustration costs of experimentation too high to justify trying out their ideas. Recognizing that many instructors wanted to simply demonstrate an idea, we decided to reduce the costs of small-scale creativity and innovation, while also managing organizational needs for compliance and resource management.

With full support and funding from the University Council, the One University Experience Project (1UEP) decided to fold the concept of Technology Demonstrator projects into our practice of supporting learning and teaching development at USQ as part of a larger suite of learning and teaching initiatives. We wanted to stimulate interest among teachers to try their ideas using some simple principles that included participation, simplicity, and short iterative cycles of development and practice. The rules that we set for ourselves included two key goals: (1) that only participants could initiate Technology Demonstrator projects, and (2) that Demonstrator support team only offer advice when asked for it. Initiators need to meet three conditions to launch a Demonstrator Project:

- The staff member must articulate what they are trying to demonstrate in one or two sentences.

- Once started, the whole project can take no longer than 90 days or one academic term.

- No current university operations can have significant dependencies on the idea being demonstrated. Specifically, the outcomes of the project cannot have significant financial, infrastructure, or human resource-based dependencies. This means these are not large, multimillion dollar projects; they are short, quick projects, simply demonstrating the value of an idea. If things don't work out as expected, we try something else (another tool or approach) to see if that assists in facilitating the educational objective. The projects also tend to be self-sustaining/supporting and do not require a great deal of additional staff support to act.

Following these three rules reduced the need for risk mitigation, generated a bit of urgency, and greatly reduced any stigma of failure should the project fail to demonstrate the desired outcomes.

"We aimed to demonstrate that the Google Plus Communities would add significant value in connecting our mostly online TEP [Tertiary Education Preparation] students. It was a bit of a gamble and didn't fully pan out, but the whole idea behind technology demonstrator project is to engage, explore, and experiment. There are no failures, and we gained valuable learning from the experience."

—Marcus Harmes, Associate Director, Academic Development

Demonstrator Outcomes

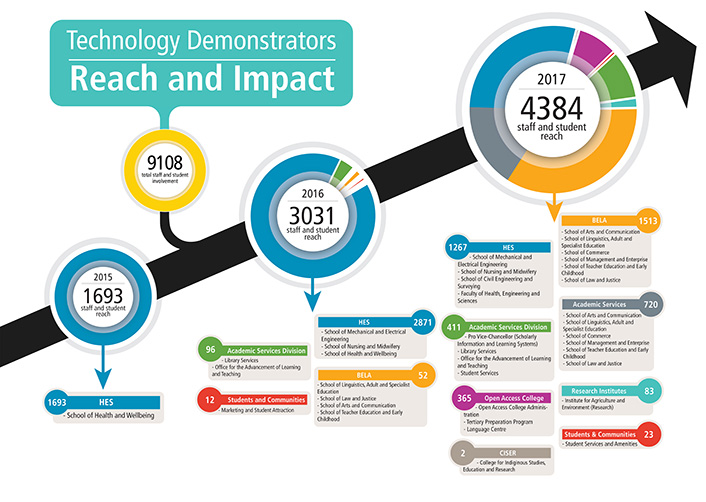

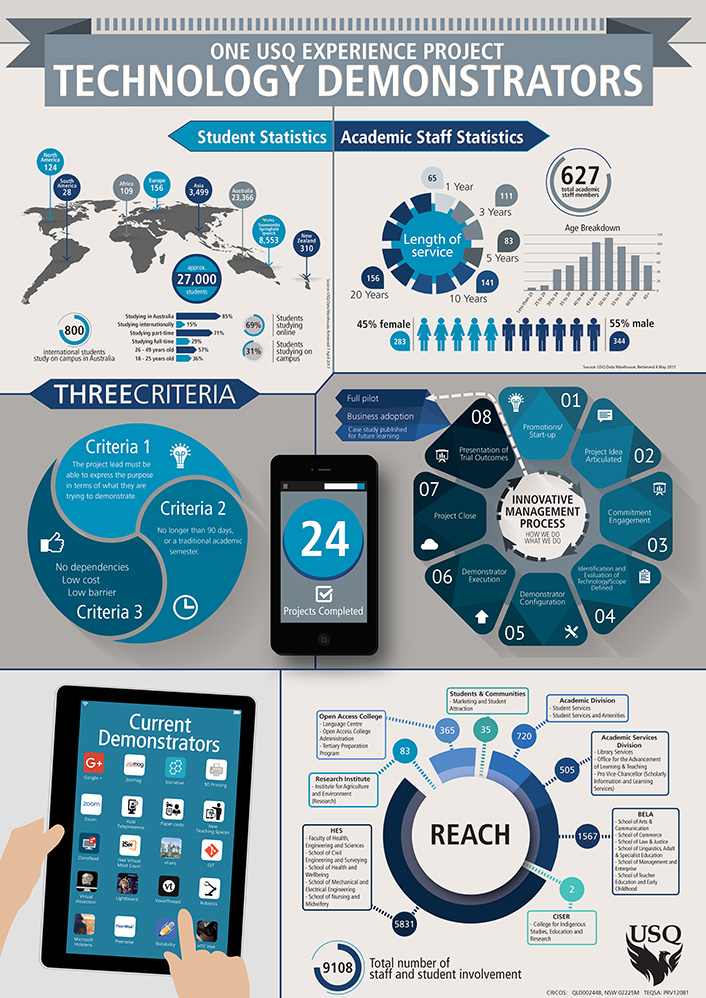

Figure 1 illustrates the eventual impact of the decision to introduce Technology Demonstrators as measured by total number of staff and students who engaged with a technology demonstrator from 2015 to 2017. Representing approximately a third of USQ's total enrolment, the eventual reach serves as one indicator of this initiative's success. Success also involved encouraging not only a culture of innovation but also sharing and disseminating our emerging experience with and knowledge about innovative technology-enabled learning and teaching. We asked demonstrators to complete a case study, and in many instances they also produced a video reflecting on their demonstrator experience. These case studies and videos [https://www.usq.edu.au/learning-teaching/innovative-teaching/technology/demonstrators] are openly shared on our website. Finally, through the Technology Demonstrator project, and in tandem with established ICT policy and procedures, USQ better articulated a model for the management and diffusion of innovation, with a poster session on Technology Demonstrators delivered at the EDUCAUSE Annual Conference 2017. Figure 2 shows how we plan to manage the diffusion of innovation within the USQ context.

The Wins

Given the opportunity to share our findings with our educational colleagues, we asked the Technology Demonstrator team, led by co-author Susan Brosnan, to reflect on and identify the top successes to date:

- Developed a robust tried and tested innovation management process

- Understanding that in terms of technology, one size does not fit all due to our diversity

- Reducing barriers/frustration/headaches via a cost vs. benefits analysis

- Giving instructors some ownership of the process, leaving them inspired by its simplicity and low barriers

"Great to finally have a supported environment for creativity and innovation."

—David Woodroffe, Team Leader, Enterprise Applications

- Organically growing appetite for innovation at USQ

- Ability to change direction easily, along with agility produced by each project's emergent design

- Unconstrained by predetermined goals, milestones, and deliverables

- Working outside existing systems and processes

- No fail — we continue to learn

- Project visibility across campus

- Just-in-time project planning (timelines mostly determined by the instructors)

- Small cross-functional team (lead, digital innovator, and training and support)

- Low cost: 26 projects used only $2,500 on technology (not including staff salaries) = lean startup

- Technology diffusion through the growing number of staff and students who have trialed these technologies and normally would not have

Some projects have looked at student diversity and explored innovative ways to improve assessment and engage students in both curricular and co-curricular activities. Many instructors expressed feeling highly motivated to innovate as they went through this process, probably because they are integral to selecting technologies to explore. We observed that the Technology Demonstrator approach empowered academics by acknowledging that our staff clearly understand their students, the context, and the challenges. After all, who better to advise on learning and teaching than our learners and teachers?

Likewise, we don't predetermine or measure outcomes of individual projects, nor do we customize anything to fit with existing USQ systems. We discovered tremendous value in being open to emergent and incidental outcomes. We also benefited from building productive relationships with venders and internal partners along the way.

We built, nurtured, talked about, and managed the Technology Demonstrators ethos to assist in growing our culture of exploring innovation, and also to grow capacity and capability in Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL).

The Challenges

Given the innovation paradox at play within our university, we (unsurprisingly) faced several ongoing challenges to the Technology Demonstrators initiative. We subscribed to the belief that behaviors influence attitudes and vice versa in a self-reinforcing cycle that can influence change. Believing in the transformative capacity of agility and not complicating things unnecessarily helped shape how we approached the challenges and planned to alter entrenched organizational attitudes. Fellow educators might identify with these challenges and remind us of the importance of professional resilience and persistence whenever we aim to introduce and influence new practices within our organizational culture. These ships we sail might well take time to turn, but we have found the journey worth it.

Fortunately, far fewer than our wins, the primary challenges we face(d) follow:

- The balance between innovation and compliance in a risk-averse university (enabling innovation and reducing barriers)

- Trying something that doesn't have the evidence of effectiveness and thinking outside the box

- Level of digital literacy skills of some teaching staff and the support required to guide them through a demonstrator

- A growing backlog of ideas waiting for demonstration, and our capacity to manage expectations

- Comfort for some teachers in doing things the way they have always done them

- Changing mindsets and leaving behind "comfort"

- Transitioning Technology Demonstrators from a discrete project into business as usual for USQ

The final challenge is currently underway and a key factor in determining the ongoing success of Technology Demonstrators.

Looking Back and Forward

Our universities face a critical need for a strategic approach to influencing a culture of innovation and realigning the balance of agility and stability. Technology Demonstrators tested this from 2015–2017 and offered a useful way to self-correct the imbalance. We found that to influence agility, we needed to model it, practice it, and promote it, and we did so through the Technology Demonstrator program. The initiative allowed some degree of working outside the usual business models to become a true incubator of exploration, experimentation, and engagement with innovative and emergent technology-enabled learning and teaching. Staff and students certainly engaged with the program, and we attribute this to the agency afforded to staff to recommend their own demonstrators in an effort to find solutions to complex and highly contextual challenges.

USQ has come to recognize the importance of the Technology Demonstrator program and has chosen to transition it into a normal feature of practice. It will serve as a key incubation strategy that can support and lead to further scholarly work in learning, teaching, and open educational practices. Given the challenges facing our universities and the increasing compliance demands, high-level endorsement of and support for a mechanism like the Technology Demonstrator program will prove essential when the strong winds of resistance blow, and blow they will.

Notes

- New Media Consortium and the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Higher Education Edition, 8.

- Geoff Sharrock, "Organising, Leading and Managing 21st Century Universities," in Visions for Australian Tertiary Education, Richard James, Sarah French, and Paula Kelley, eds. (Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, February 2017), 36; ISBN: 978-0-7340-5341-1.

- Wouter Aghina, Aaron De Smet, and Kirsten Weerda, "Agility: It Rhymes With Stability," McKinsey Quarterly (December 2015): 1–12.

Susan Brosnan was the senior technologies adviser and lead of the Technology Demonstrator Project, ICT – University of Southern Queensland.

Ken Udas is former deputy vice chancellor, Academic Services, and CIO, University of Southern Queensland.

Bill Wade is manager, Educational Futures, University of Southern Queensland.

© 2017 Susan Brosnan, Ken Udas, and Bill Wade. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0.