"How does this kitchen look like other kitchens you've seen? How does it look different?" an instructional designer asks students in a course called Global Poverty and Care.

Several students raise their hands. "Those handles look easy to grab," one says.

"The counters look like they can accommodate wheelchairs and kids!" another one shares.

"Look! You can't make a mess on the counter. If you spill, there's a lip on the edge of the counter, preventing it from getting on the floor," a student in the back says excitedly.

These students are looking at the Rhode Island School of Design: Universal Kitchen, a project of Marc Harrison, one of the earliest designers to advocate for universal design (UD) principles in the field of industrial design. The prototype kitchen, showcased at the Cooper Hewitt Museum in 1998, is a powerful example illustrating the core principle of universal design: Designing for the widest set of needs improves the experience of all users. This conversation is part of a larger initiative at Dartmouth College to educate and empower the community around the principles of universal design.

In higher education, discussions around accessibility often start with federal mandates and accommodations. This framing tends to cultivate a campus culture focused on accommodations, but "...accommodation is a reactive approach to provide access to an individual ... [whereas] UD processes are proactive approaches to ensure access for groups of potential participants."1

At Dartmouth, we realized that this distinction creates an opportunity for changes in both teaching and learning. While some legal requirements for accessibility are not necessarily met through the practice of universal design, we hope to guide our institution toward a culture aimed at designing for the widest possible set of student needs.

Starting with Course Design

As instructional designers, we collaborate with faculty on both the design and teaching of their courses. Over the past few years, focusing these collaborations around UD principles has enabled us to introduce the notion that differences in learning profiles should be expected and incorporated into the design of learning experiences.

Faculty often receive requests — via our Student Accessibility Services office — for accommodations for a variety of student needs, including a disability, a life circumstance change, or a mental health concern. These requests can lead to confusion, anxiety, and frustration for the faculty. We realized that our campus required a new approach to engaging with faculty around student needs, accommodations, and UD. Our new focus includes an introduction of UD principles in both course design and specific accommodation needs.

The course mentioned above started as one of these cases. The professor, Patricia Lopez, had questions about accommodation requests, and she set up a consult with Adam Nemeroff to talk about the impact of these changes in her course and how she could be more proactive about incorporating a design that addresses both the accommodations as well as the needs of the rest of the class.

"Like many faculty, I can be stubborn about disruptions to my usual workflow. I enjoy the flexibility afforded by an online syllabus, and I almost never have a complete course website up for the first day of class. I often work on lectures up to the last minute before each class, and I fiddle with extra media materials as things come floating by in my daily life.

Because of my own struggles with ADD, I was already cautious about how I organize the content of the course website. It is organized to accommodate as many different learning styles as possible. Everything is cross-referenced and can be accessed either through a linear progression or through weekly modules. The readings are all cleaned and free of markings, and scans are meticulously taken and flattened to ensure that OCR text recognition software can easily discern independent letters and words.

However, as I quickly learned throughout the meetings, my usual habits would no longer suffice, and my attempts to be as accessible as possible fell considerably short." — Lopez

This gave rise to a series of short consultations focusing on Lopez's course design, teaching methods, and instructional materials and on supporting UD in student group presentations in their culminating learning projects. In addition to these one-on-one consultations, we have also convened broader gatherings of students, faculty, and staff who express interest in the topic of UD. Although we can effect some changes through consulting with individual faculty about specific courses, we also need to facilitate collaboration across institutional resources and services.

Getting Together

Many people in a variety of roles on our campus have been trying to effect change in UD. Students have been vocal self-advocates, faculty have worked to increase the accessibility of their courses, and staff have supported these efforts through course design, accommodation support, and technological solutions. Our next step was to gather these individuals across departments to organize and coordinate our efforts.

Representatives from Student Accessibility Services, Classroom Technology Services, and Instructional Design gathered with a project manager to form a group we dubbed Team Access. The purpose of this group is to leverage our collective knowledge to approach student accommodations and faculty development more proactively and purposefully.

"The more I chatted with specialists and learned the components of universal design, the more I came to appreciate the importance of planning ahead — of ensuring that course materials are accessible to everyone before an accessibility need arises. As we worked through the different ways that I could make the course easier for a single student, the more I realized that working from a starting point of universal design is a form of care ethics. Despite my own frantic concerns about meeting the one student's needs, it dawned on me that there are so many students whose needs go unremarked, undiagnosed, or otherwise unknown for a variety of reasons. To be truly caring, to engage from the point of care ethics, is to act in such a way as to preclude the need for 'adjustments' for one or two students and to be prepared for the wide variety of student needs." — Lopez

Generating Effective Solutions: A Framework

As instructional designers, we are prepared with frameworks and processes intended to support the course design process. The original UD principles2 were developed for designers to make products (such as the kitchen described above) and services accessible:

- Equitable use

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Perceptible information

- Tolerance for error

- Low physical effort

- Size and space for approach and use

Universal design for instruction (UDI) and universal design for learning (UDL) are different interpretations of these principles, focused on employing these principles in both teaching and learning contexts:

"In terms of learning, universal design means the design of instructional materials and activities that makes the learning goals achievable by individuals with wide differences in their abilities to see, hear, speak, move, read, write, understand English, attend, organize, engage, and remember. Universal design for learning is achieved by means of flexible curricular materials and activities that provide alternatives for students with differing abilities. These alternatives are built into the instructional design and operating systems of educational materials-they are not added on after-the-fact."3

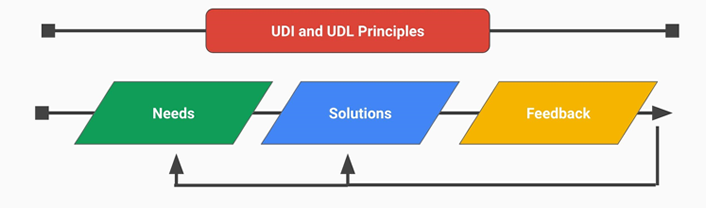

These interpretations form the backbone for both our campus strategy and the designs of our specific engagements with students, faculty, courses, and projects. Team Access used this backbone to develop a three-phase, human-centered design approach to change. The first phase involves identifying users, building empathy, and conducting a comprehensive needs analysis. The second phase involves the design and development of prototypes, ideas, and solutions. The third phase involves the design and collection of comprehensive feedback mechanisms for the solutions from our identified stakeholders (see figure 1).

People and Needs

The audience for any UD effort needs to include all of the individuals engaged in the teaching and learning enterprise. This approach accounts for the engagement of students, faculty, instructional designers, support staff, and administrators. For this article, we will focus on the needs of students and faculty. Starting from a student perspective, UD requires an understanding of the student's learning profile, the needs of other learners in the course, and the faculty's pedagogical approach and existing skills and experiences.

This process of relationship building yields the most important outcome in our projects. By engaging directly with both a needs analysis and empathy building, Team Access is able to facilitate conversations and communication that address many issues from the start. Students already receiving accommodations via our Student Accessibility Services office are now building a space to engage in a structured and meaningful exchange with their instructors around their learning profile and needs, but all students are hopefully feeling more invited to engage in these discussions. It also appears that through the process of reflecting on their learning, students become more aware of their learning strategies, approaches, and abilities to self-regulate.

In the case of the Global Poverty and Care course, we worked with Lopez to review the student profiles we received from Student Accessibility Services. This included needs to accommodate a student with low vision, as well as students with print-based disabilities. We talked about who the students are who take this course and how we could learn about their needs when the course started. Beyond traditional accommodations, we realized that students in this course had a wide variety of needs that included everything from being from an underrepresented group in higher education to being English language learners. Additionally, it was important to articulate Lopez's needs as an instructor. For example, the nature of the course requires that content remain somewhat adaptable to student needs. All of this was taken into consideration as we developed the needs profile for the course.

While the college has official syllabus language pertaining to accessibility needs, Lopez includes extra language:

"I also recognize that students may have health, mental, or physical issues and concerns that are unrecognized by Student Accessibility Services or are otherwise undocumented. Please note that I fully respect your privacy, and while it would be helpful for me to be made aware early in the course in order that I may better accommodate your needs, I do not require official notification. I encourage you to do what you need in order to be successful in the course. At the same time, I expect all students to be respectful to other students' needs. We all learn and engage differently in classroom, group, and individual work." — From Lopez's syllabus

Solutions

Understanding the needs of these stakeholders leads into a brainstorm focused on "solution development." This includes the documentation of specifications for the design, an actual design, and a development of prototype tools and techniques intended to meet those needs. Our goal is to get these solutions into our project settings quickly and to iterate based on what we learn.

We quickly realized that faculty lacked the tools necessary to determine their students' ability to access instructional materials across diverse needs. This gave rise to implementing UDOIT, a Canvas LTI aimed at content inspection for UD principles and web standards. Initially we prototyped engaging with faculty around UDOIT, trying different approaches to scanning documents, and using accessibility features built into tools found in the Office 365 and Google Apps ecosystems.

Lopez and Nemeroff worked to identify specific needs across the course. This included understanding how information was presented in class, the accessibility of information on Canvas using UDOIT, the need for lecture capture in the classroom space, and how to support students in making their own presentations accessible.

"I insisted that this is a lifelong skill, not merely a classroom skill — something they can take with them as they move into the world of work. It went beautifully, and I plan to continue to include a universal design module in all of my courses that have presentations." — Lopez

In the near future, Team Access hopes to expand this suite of solutions to include a self-service closed-captioning workflow for faculty-created media and better support assessments that measure student learning, beyond allocating extra time for specific individuals in an exam. We hope that the three-phase model will generate prototypes and solutions aimed at meeting individuals' needs.

Feedback and Sustainability

Gathering feedback on the success of these solutions and developing plans for scaling them are key components for the work of Team Access, enabling us to perform ongoing refinements and improvements at all stages of our process. We perform this not only at the project/course level but also with the team's processes. This is often a space where we flag how team resources are being used and where those things could be improved. It's at this point that we explore the effectiveness, sustainability, and scalability of our solutions. This then sets up the groundwork for future planning.

Nemeroff and Lopez refined the solutions throughout the course offering. Student Accessibility Services and Classroom Technology Services also participated as needed. At the end of this engagement, students reflected on how UD impacted their experience, and Team Access collected feedback from Lopez on how best to support her and other faculty in these efforts.

"Needing to provide multimedia materials in advance has, in the end, saved me time. Like many professors, I scramble to provide the most current news clips, blog posts, and other media — the more current we are with examples, the more meaningful the theories become to their own lives. I was admittedly concerned about the possible limitations of having to choose in advance. However, as I quickly learned, it was a relief to no longer waste valuable class prep time searching for new items. I had to work with what I had. On the rare occasion that I added an extra piece, I e-mailed the class in advance. I now do this for all of my classes. Many students have a difficult time staying focused in class, and having access to materials beforehand or for follow up is helpful for a wide range of students. Further, if I run out of time and am unable to share multimedia during our class time, students now have access to the material.

It also turns out that our students are not as graph literate as I assumed. A 2011 study, published in Medical Decision Making, found that one-third of Americans and one-third of Germans between the ages 25 and 69 have low graph literacy. Describing the visual aids in my slideshow turns out to be important to all students and has now become a standard practice in my lectures. At the same time, this has slowed my lectures down to a pace that students can better follow. I often worry about getting through all of the material for each class meeting, and I have not always paid attention to the pace at which I am galloping through my lecture notes and slides. Learning to slow down has proved invaluable to the students (and was reflected in fewer complaints about my lectures!)." — Lopez

Organizing Resources and Vertical Buy-In

In order to ignite a campus "UD first" mindset, we need to adopt an inclusive approach for engagement. The driving force for the changes needs to be the faculty and the students. However, it's also necessary to engage with all of the individuals engaged in the teaching and learning enterprise.

In addition to the stakeholders within the experience and those supporting the experience, budget managers and campus decision makers also need to be on our radar. These individuals can advocate for and secure the funds necessary to resource the changes. At Dartmouth, the Student Accessibility Services office is a key partner in driving this charge. Examples such as the class described here may feel more grassroots than system-wide at this stage, but we know that these sparks will lead to a flame. Already, the members of Lopez's department have requested a workshop to discuss these ideas and plan for their own courses.

Ultimately, the more you make "UD first" a mindset rather than an activity in response to legal requirements, the easier it is to make both time and space for it — universal design becomes what you do by default. It's a challenge, but it's also an opportunity for us. By taking on this effort, we hope to embark on those first important steps toward building a more inclusive and accessible campus in every aspect.

Further Reading

Fisher, Berenice, and Joan C. Tronto, "Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring," in Circles of Care, ed. E. K. Abel and M. Nelson (Albany: SUNY Press, 1990).

Robinson, Fiona, The Ethics of Care: A Feminist Approach to Human Security (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011).

Notes

- Sheryl E. Burgstahler, "Universal Design in Higher Education," in Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice, ed. Sheryl E. Burgstahler and Rebecca Cory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2013), 3–20.

- Bettye Rose Connell, Mike Jones, Ron Mace, Jim Mueller, Abir Mullick, Elaine Ostroff, Jon Sanford, Ed Steinfeld, Molly Story, and Gregg Vanderheiden, "The Principles of Universal Design," North Carolina State University, Center for Universal Design, 1997.

- Council for Exceptional Children, Universal Design for Learning: A Guide for Teachers and Education Professionals (London: Pearson, 2005), 2.

Erin DeSilva is an Instructional Designer at Dartmouth College.

Adam Nemeroff is an Instructional Designer at Dartmouth College.

Patricia J. Lopez is an Assistant Professor of Geography at Dartmouth College.

© 2017 Erin DeSilva, Adam Nemeroff, and Patricia J. Lopez. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.