Preamble

The Catalog as an Identifiable Service

There is a renaissance of interest in the catalog and catalog data. Yet it comes at a time when the catalog itself is being reconfigured in ways which may result in its disappearance as an individually identifiable component of library service.1 It is being subsumed within larger library discovery environments and catalog data is flowing into other systems and services. This article discusses the position of the catalog and uses it to illustrate more general discovery and workflow directions.2

The context of information use and creation has changed as it transitions from a world of physical distribution to one of digital distribution. In parallel, our focus shifts from the local (the library or the bookstore or …) to the network as a whole. We turn to Google, or to Amazon, or to Expedia, or to the BBC. Think of two trends in a network environment, which I term here the attention switch and the workflow switch. Each has implications for the catalog, as it pushes the potential catalog user in other directions. Each also potentially recasts the role of the catalog in the overall information value chain.

The catalog emerged at a time when information resources were scarce and attention was abundant. Scarce because there were relatively few sources for particular documents or research materials: they were distributed in print, collected in libraries and were locally available. If you wanted to consult books or journal or research reports or maps or government documents you went to the library. However, the situation is now reversed: information resources are abundant and attention is scarce. The network user has many information resources available to him or her on the network. Research and learning materials may be available through many services, and there is no need for physical proximity. Furthermore, users often turn first to the major network level hubs which scale to provide access to what is visible across the whole network (think, for example, of Google, Wikipedia, Amazon, and PubMed Central). This is natural as interest gravitates to the more complete resource rather than a local selection which seems increasingly partial. Studies show the high value placed on convenience and the importance of satisficing: users do not want to spend a long time prospecting for information resources.3

The second trend is related. In an environment of scarce information resources and physical access, users would build their workflow around the library. This centrality was visible in the corresponding centrality of library buildings on campus or in communities. However, on the network, we increasingly expect services to be built around our workflows. And this has led to resources being designed to be present to us in multiple ways. Think of the variety of ways in which the BBC, Netflix or Amazon tries to reach its users, and the variety of experiences — or workflow integrations — they offer. Think of the Whispersynch feature of the Kindle for example, which allows a continuous reading experience across multiple network entry points (phones, tablets, PCs, e-reader, etc.). Or think of the multiple ways in which the BBC or Netflix makes programming available (website, iPlayer, apps).

The catalog has been an institutional resource. How does it operate in this network environment? Some trends have been to make the data work harder (facets, FRBR, etc.), syndicating data to other environments (learning management, Google Book Search, etc.), developing apps, widgets, and toolbars to move the catalog closer to the workflow.

At the same time the catalog itself may give way to other environments that may deploy catalog data. An important case is discovery across the whole library collection, not just the "cataloged" material. Another is the desire to see catalog resources represented in higher-level "group" services (e.g., OhioLink, the German Verbundkataloge, Copac in the UK) and in web-scale services (Worldcat, Google, Goodreads). Another again is to desire to reuse catalog data in personal and institutional curation environments (resource guides, reading lists, citation managers, social reading sites).

There have also been developments with the data itself. Catalog data is closely associated with print and other physical collections. As more of these materials become digital, as they are related to each other in various ways, and as they are delivered in packages rather than volume by volume, this raises issues for the management of metadata about them. At the same time, there is an interest in more closely aligning data structures with the broader web environment. And knowledge organization systems may also be reconfigured by network approaches.

Ironically, then, as a set of issues around the catalog is more clearly coming into relief, it may be that the classic catalog itself may be receding from view. Its functionality and methods may not disappear, but they may be unbundled from the catalog itself and rebundled in changing network discovery and workflow environments.

In this piece, I copy Stevens's conceit in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Even though this results in some repetition it seemed appropriate to a topic about which we don't yet have a single story. Much of the discussion is relatively neutral, covering recent developments. I bracket these 13 sections with this introduction and with a conclusion that looks beyond current developments to speculate about likely direction.

Environmental: The Library in the Network

1. Moving to the Network Level: Web Scale

In a physical world, materials were distributed to multiple locations where they were organized for access by a local user population. In this way, the institution was the natural focus for discovery: a catalog described what was locally available. It provided breadth of access across a large part of what a user was interested in: that which they could gain access to in the library. It was at the right scale in a world of institutional access: it was at institution-scale. Similarly a record store was the natural focus for discovery and purchase of music, or a travel agent for discovery and purchase of flight or rail tickets. They aggregated materials, services, and expertise close to their users.

However, access and discovery have now scaled to the level of the network: they are web scale. If I want to know if a particular book exists I may look in Google Book Search or in Amazon, or in a social reading site, in a library aggregation like Worldcat, and so on. My options have multiplied and the breadth of interest of the library catalog is diminished: it provides access only to a part of what I am potentially interested in.

In this context, it is interesting to note the longitudinal study of faculty use of the library carried out by Ithaka S+R.4 They have observed a declining role for the "gateway" function of the library, partly because it is at the wrong level or scale. Google and other network level services have become important gateways.

What are the implications for an institution-level service like the catalog in a world where much of our access has moved to the network level? We can see several responses being worked through, although it is not clear which will be most effective in the longer term. These include network level consolidation strategies (think of HathiTrust, Worldcat, Europeana, Melvyl, Libraries Australia), syndication and leveraging strategies (where library resources are directly connected to network level resources, as where Google Scholar or Mendeley recognize your institution's resolver, for example), and open approaches whether at the API or the data level (where others can reuse catalog data or services). This phenomenon highlights the important locator or inventory role of the catalog or local discovery environment. While discovery and exploration may move elsewhere, such external discovery environments may link to the library environment for location and fulfillment.

2. Not a Single Destination: Multiple Presences on the Web

We sometimes still think of the website as the focus of institutional presence on the network. And, often, mobile or other presences are seen as derivative. Clearly the importance of mobile has changed that view and changed the way we think about design and expectations.5

The boundary between "mobile" and fixed has dissolved into multiple connection points, each with its own grade of experience and functional expectations (the cellphone, the tablet, the desktop, the iPad app, the xBox or Wii, the Kindle or Nook, the media center, the widget or gadget, the social networking site). At the same time, more functions are being externalized to network-level providers of communications and other services (e.g., Facebook, YouTube, Flickr). Providing service in this environment is very different than in one where the model assumes a personal desktop or laptop as the place where resources are accessed and used and the institutional website as the unified place where they are delivered. As our entry points have become more varied, what might have been on the website is being variably distributed across these entry points. So, selected information may be on a Facebook page, selected functionality may be available through apps and widgets, selected communications may be available on Twitter, and so on.

Libraries have worked with their discovery services in this context. We have seen the catalog "put" in multiple places, in Facebook, in Libx style toolbars, in widgets, apps and gadgets, and in mobile apps. Interesting as some of these developments have been, they have highlighted three issues. First, there is the divorce between discovery and delivery. The mobile experience shares with the app a preference for simplicity: it is important to do one thing well. It is also important to get to relevance quickly. The catalog may not be best suited here, as the connection to delivery is often not immediate, and accordingly may not be directly applicable in such environments. Second, and related, we are seeing a reconfiguration of functions in app/mobile environments, as functionality is disembedded from the fuller website experience and re-embedded in smaller more discrete experiences. Computer or meeting room availability and scheduling in the library is an example. In this context, it is interesting to think about what types of catalog functionality lend themselves to this treatment: a simple search may not be the best choice. Finally, while the catalog is interesting, attention is shifting to the full collection — across print, licensed and digital — and to the discovery layers which make them available. Should the mobile app be at this level or at the level of the catalog?

3. Community is the New Content: Social and Analytics

The interaction of community and resources — in terms of discussion, recommendation, reviews, ratings and so on — is evident in some form in most of the major network services we use (Amazon, iTunes, Netflix, Flickr). Indeed, this is now so much a part of our experience that sites without this experience can seem bleached somehow, like black and white television in a color world.

Think of two aspects of our interaction with resources: social objects and analytics.

People connect and share themselves through "social objects" (music, photos, video, links, or other shared interests) and it has been argued that successful social networks are those which form around such social objects.6 This encourages reviewing, tagging, commenting. We rate and review, or create collections, lists, and playlists, which disclose our interests and can be compared to make recommendations or connect us to other users based on shared interests (think of Last.fm or GoodReads, for example). We are becoming used to selective disclosure and selective socialization through affinity groups within different social networks. Together, these experiences have created an interesting expectation: many network resources are "signed" in the sense that they are attached to online personas that we may or may not know in "real life," but whose judgment and network presence we may come to know. Think of social bookmarking sites or Amazon reviews, for example, or social reading sites. And although a minority of people may participate in this way, their contribution is important in the overall experience of the site. People are resources on the network, and have become connectors for others.

Second, as we traverse the network we leave an invisible data trail in our wake; we leave traces everywhere. We click, navigate, and we spend both money and time. Services collect this subterranean data and use it to transform our experience. They do this by providing context and by configuring resources by patterns of relations created by shared user interests and choices. Google revolutionized searching on the web by recognizing that not all websites are equal, and by mobilizing linking behaviors; Amazon made "people who bought this, also bought this" types of association popular. iTunes will let me know about related music choices.

An important part of each of these trends is that it is an emergent response to the issue of abundance. Where resources are abundant and attention is scarce, the filtering that social approaches and the use of analytics provide, becomes more valuable. The data that users leave, intentionally in the form of tags, reviews and so on, or unintentionally, in the form of usage data, refines how they, and others, interact with resources. They allow services to more effectively rank, relate and recommend.

What about the catalog in this context? Some catalogs have experimented with collecting tags and reviews but it does not seem that the catalog has the centrality, scale, or personal connection to crystallize social activity on its own. There is some activity at the aggregate level (e.g., Worldcat, BiblioCommons) and there is some syndication of social data from commercial social collecting/reading sites (e.g., LibraryThing). Similarly, catalogs have not generally mobilized usage data to rank, relate or recommend, and again this seems like something that might best be done at the aggregate level, and syndicated locally (as with the Bx service from Ex Libris, for example).

There are some places where catalog data gets used — reading lists and resource guides, for example — which seem to be especially appropriate for such attention. The choices involved in this additional layer of curation could be aggregated to provide useful intelligence. What items occur frequently on reading lists, for example? Would it be useful to provide an environment where students rate, review or comment on assigned readings? Is there enough commonality across institutions to make it useful to aggregate this data?

Our web experiences are now actively shaped by ranking, relating and recommending approaches based on social and usage data. For library services this is a major organizational challenge, as supra-institutional approaches may be required to generate appropriate scale.

4. The Simple Single Search Box and the Rich Texture of Suggestion

We are used to hearing people talk about the "simple search box" as a goal. But, a simple search box has only been one part of the Google formula. Pagerank has been very important in providing a good user experience, and Google has progressively added functionality as it included more resources in the search results. It also pulls targeted results to the top of the page (sports results, weather or movie times, for example), and it interjects specific categories of results in the general stream (news, images). Recently Google has begun pulling data from its "Knowledge Graph" — a resource created from Freebase, mined user traffic, and other sources — and presenting that alongside results. Amazon also has a simple search box, but search results open out onto a rich texture of suggestion as it mobilizes social and usage data to surround results with recommendations, related works and so on. In fact, the Amazon experience has become very rich with the opportunity to rate reviews themselves, to preview text or music, to look at author/artist pages, to check Amazon-enabled Wikipedia pages, and so on.

We can see this emerge as a pattern: a simple entry point opens into a richer navigation and suggestion space. In this way, the user is not asked to make choices up front by closely specifying a query. Rather they refine a result by limiting by facets (e.g., format, language, subject, date of publication, etc.), or they branch out in other directions by following suggestions. This is also emerging in our library discovery environments which are moving to think about how to better exploit the structure of the data to create navigable relations (faceted browsing, work clusters). We are making our data work harder to support interesting and useful experiences.

A next step is actually to recombine the record-based data into resources about entities of interest. The work on FRBR is an example here, to show a work as it is represented in versions and editions. Author or creator pages is another case. See Worldcat Identities for an example of this approach.

Finally, one might note here an interesting difference in approach between a single stream of results across formats (with the ability to filter out using facets), and a multiple pane approach ("bento box")7 where results for a particular format or resource stream in an individual pane. There may be usability arguments for this approach, but a principal issue is synthesizing ranking approaches across quite different resources. The "bento box" style mitigates this issue by presenting multiple streams of results. This approach is used to good effect in Trove, the discovery system developed by the National Library of Australia. Several institutions use Blacklight to supported more well-seamed integration between results from, say, a discovery layer product, a catalog, other local data, and so on, where local control is desired. Again, the bento box approach is common here.

Institutional: The Library

5. An Integrated Experience

The library website aims to project a unified library experience, not a set of unrelated opportunities. This is harder than it might at first seem because typically the website provides a layer over a variety of heterogeneous resources. There is the administrative information about organization, strategy, facilities and so on. There is information about library services and specialist expertise. And there are various information systems — catalog, discovery layer, repository, resource guides, and so on.

If we look at the information systems aspect of the website, we can see that the library has been managing a thin integration layer over two sets of resources, which has created challenges in creating an integrated experience. One is the set of legacy and emerging management systems, developed independently rather than as part of an overall library experience, with different fulfillment options, different metadata models, and so on. These include the integrated library system, resolver, knowledge base, and repositories. The second is the set of legacy database and repository boundaries that map more to historically evolved publisher configurations and business decisions than to user needs or behaviors (for example, A&I databases, e-journals, e-books, and other types of content, which may be difficult to slice and dice in useful ways). From a user perspective these distinctions are variably important. A student may want access to a unified index across many resources. A researcher may still be interested in a particular disciplinary database, independently of its merger into a larger resource. The desire for better integration has been supported by the emergence of discovery layer products.

This push for a unified experience has also influenced the construction of websites, and has promoted the alignment of user experience across the services presented in the website. So, for example, libraries are using approaches like Libguides or Library à la Carte to assemble subject or resource guides. It may also now be more common to use a content management system to support the library website, or it may use a wider institutional one. This enhances the sense of the pages as a professionally curated resource, and seems to support better overall UI consistency. What about the catalog in this context? It is a little shocking still to experience a complete transition in navigation and design when going from some general websites to a page with a catalog on it. Modernizing these catalogs — making them more "webby" — was an important part of the interest a while ago in "next-generation catalogs" and now in the discovery layer product. It is also apparent in the use of Drupal, VuFind, or Blacklight to provide a more integrated approach across such tools.

6. Four Sources of Metadata about Things

We are very focused on bibliographic data and have evolved a sophisticated national and international apparatus around the creation and sharing of catalog data. National libraries, union catalogs, and commercial sources of record supply all play a part. That apparatus is likely to change in coming years, as the nature of physical collections change and as more data is assembled in packages associated with e-book collections or other significant sets (HathiTrust or Google Books, for example). A further pressure for change is the need to free time or attention for digital materials, archives, or other materials which the library needs to record but which are typically outside the current collectively managed bibliographic apparatus. The nature of the metadata of interest may also change. I have found it useful to think of four sources of metadata about library materials.

Professional: Produced by staff in support of particular business aims. Think of cataloguing, or data produced within the book industry, or A&I data. This is the type of metadata that has dominated library discussion. While the approach has worked reasonably well in the physical publishing environment, where the work, or the cost of the work, could be shared across groups of libraries, we are seeing that it may not scale for digital materials and poses issues for special and archival materials.

Crowdsourced: Produced by users of systems. Think of tags, reviews and ratings on consumer sites. This type of metadata has been less widely used on library sites for reasons discussed above. Although libraries are social organizations, the library website or catalog is probably at the wrong level to crystallize activity. One area with some promise is asking for user input on rare or special materials, where the library will not have local or specialist knowledge about contents. Think of digitized community photographs for example.

Programmatically promoted:Produced by automatic extraction of metadata from digital files, automatic classification, entity identification, and so on. This will become more common, but will require tools and practices to become more widespread. We can see how this would be useful as we look at describing digital documents, web resources, images, and so on. As digital resources become more common so will these methods. Of course, they may go hand in hand with "professional" approaches, as, for example, names extracted from text are matched against authority files.

Intentional or transactional: Produced from data about choices and transactions. This data supports analytics or business intelligence services. Think about ranking, relating, recommending in consumer sites (e.g., people who like this also like this) based on collected transaction data. I have also discussed this type of data above, and again for it to be very useful it is likely that it needs to be aggregated above the institutional level and made available back to the library. We are beginning to see some examples of this.

What I call here crowdsourced, programmatically promoted, and intentional data are all again ways of managing abundance. Our model to date has been a "professional" one, where metadata is manually created by trained staff. This model may not scale very well with large volumes of digital material or as it becomes more common to license e-books in packages. Nor does it necessarily anticipate the variety of ways in which resources might be related. The other sources of metadata discussed here will become increasingly important. For libraries and the industry supporting them, this means thinking about sustainable ways of generating this type of data for use throughout the library domain.

7. In the Flow

Libraries are working hard to place bibliographic data or services more directly in the workflow, as workflows are variously reconfigured in a network environment. Practices here are evolving but here are some examples, pulled together in three overlapping categories: institutional and personal curation, syndication, and leverage. Increasingly libraries understand that their users may encounter bibliographic references in places other than the library's own web presence. The challenge then may be twofold: first, in some cases, to support the deployment of bibliographic data in these places (e.g., reading lists, learning management systems, citation managers) and second, to provide a path into library resources for users for whom discovery happens elsewhere in this way.

Think of this range: lists, reading lists, resource guides, personal bibliography, researcher/expertise pages, citation managers, reading management sites, campus publication lists. They all involve the management of bibliographic data to serve some end, and may draw on data across the catalog, A&I resources, and elsewhere. In some ways they are like bibliographic playlists, selections curated to meet particular personal, pedagogical or research goals. In this way they provide useful contextual framing for the items included. Products have emerged to support particular requirements. Think of Libguides for example, which provides a framework for managing resource guides, or the range of reading management sites (Anobii, Shelfari, GoodReads, Librarything). There is quite a lot of activity around researcher/expertise page management, with or without the assistance of third party tools or services. Think here of Vivo, Bepress, Community of Science. There is growing interest in managing institutional bibliographies, especially where some form of research assessment is in place and CRISes (Current Research Information Systems) such as Symplectic, Pure from Atira (recently acquired by Elsevier), and Research in View from Thomson Reuters have a bibliographic dimension. And of course, faculty and students want to manage their references, again using a variety of approaches (Easybib, Zotero, Mendeley, Refworks). I put these service areas together because typically they involve collection of metadata from several resources, and ideally they link back through to library resources where it makes sense. However, the connective tissue to achieve this conveniently is not really in place. Think of reading lists, for example, which are common in the UK and elsewhere, though less so in the US. Often, they involve a lot of mechanical labor on the part of faculty to assemble, and they may not easily link through to the most relevant library resources. The ability to create these playlist-style services, drawing on library resources where relevant, and to link them to relevant fulfillment options, is an area where attention would be useful.

The second category I mention is syndication. By this I mean the direct work the library does to place access to the catalog or discovery layer in other environments. One might syndicate services or data. Think of providing access to catalog resources in the learning management system or student portal. Think of RSS feeds, widgets, toolbars, and so on which can be surfaced in blogs and other websites. Think of Facebook or mobile apps. On the data side, think of how libraries and the organizations working with them are interested in better exposing data to search engines or other aggregators. Of particular interest here is visibility with Google Book Search and Google Scholar. In the former case, Google works with union catalog organizations around the world, including OCLC and Worldcat, to place a "find in a library" link on book search results. In the latter, Google has worked with libraries to link back to library materials through their resolvers. More generally, libraries have become more interested in general search engine optimization principles across the range of their resources. They recognize that findability or discoverability in the search engines is an important goal.

Finally, leverage is a clumsy expression used here to refer to the use of a discovery environment which is outside of the library's control to bring people back into the catalog environment. Think of the Libx toolbar, for example, which can recognize an ISBN in a web page and use that to search the home library catalog. Or think of adding links in Wikipedia to special collections on relevant entries. Leverage might overlap with a syndication approach, as with the relationship between Google Scholar and an institutional resolver.

The use and mobilization of bibliographic data and services outside the library catalog is an increasingly important part of library activity.8 This is especially important as "discovery increasingly happens elsewhere" – in other environments than in the library.

8. Outside-In and Inside-Out: Discovery and Discoverability

Throughout much of their recent existence, libraries have managed an "outside-in range" of resources: they have acquired books, journals, databases, and other materials from external sources and provided discovery systems for their local constituency over what they own or license. As I have discussed, this discovery apparatus has evolved, and now comprises catalog, A to Z lists, resource guides, maybe a discovery layer product, and other services. There is better integration. However, more recently, the institution, and the library, has acquired a new discovery challenge. The institution is also a producer of a range of information resources: digitized images or special collections, learning and research materials, research data, administrative records (website, prospectuses, etc.), and so on. And how effectively to disclose this material is of growing interest across libraries or across the institutions of which the library is a part. This presents an "inside-out" challenge, as here the library wants the material to be discovered by their own constituency but often also by a general web population.9 The discovery dynamic varies across these types of resources. The contribution of the University of Minnesota report mentioned earlier is to try to explain that dynamic and develop response strategies.

In the outside-in case, the goal is to help researchers and students at the home institution to find resources of interest to them across the broad output of available research and learning materials. In the inside-out case, the goal is to help researchers and students at any institution to find resources of interest to them across the output of the institution itself. In other words, the goal in the inside-out case is to promote discoverability of institutional resources, or to have them discovered. This creates an interest in search engine optimization, syndication of metadata through OAI-PMH or RSS, collection-specific promotion and interpretation through blogs, and general marketing activity.

Organizational: Working across Libraries

9. The Emergence of the Discovery Layer: From Full Collection Discovery to Full Library Discovery

The catalog has provided access to a part only of the collection. However, increasingly, the library would like the user to discover a fuller range, not only the full collection but also expertise and other capacities.

Think of collections first. Historically the catalog provided access to materials that are bought and processed within the cataloging/integrated library system workflow. Materials that are licensed pass through a different workflow and historically have had different processing and discovery systems associated with them (knowledge base, metasearch, resolver). Similarly, institutionally digitized or born-digital materials have yet other workflows and systems associated with them (repository, scanning, preservation).

As noted above, a major recent trend has been to provide an integrated discovery environment over all of these materials, and a new systems category — the discovery layer — has emerged to enable this. This embraces catalog data as one of its parts — and whether or not the catalog remains individually accessible is an open question.

Such systems depend on aggregating data from many sources, providing an integrated index, and typically access to a centralized or "cloud-based" resource. While many libraries see these systems as a necessary integrating step, it will be interesting to see how the model develops. Now, the model is still one in which each library has its own view on the data, which is linked to local environments through the resolver/knowledge base and local catalog apparatus. However, maybe over time, the model will shift and libraries will register their holdings with one or more central services and manage the authentication/authorization framework to determine what parts of such central services their users have access to.

The discovery layer raises some interesting questions for practice. How should the results be presented? As a single stream? Or sectioned by format as is nicely done in results from Trove at the National Library of Australia for example (note the ranking discussion above).10 There are some longer term metadata issues. Where this service is offered, the catalog data is mixed with data for articles, for digital collections and so on. What this means is that differently structured data is mixed. Catalog data will have subject data (LCSH or Dewey, for example), names controlled with authority files, and so on. Other data is created in different regimes and will not have this structure.

What does this mean for library metadata? A certain amount of mapping and normalization is possible and is done at various levels (library, service provider). Should national libraries extend the scope of their authority files beyond cataloged materials, to include, for example, authors of journal articles? There may be greater integration at the network level, between initiatives like VIAF, which brings together authority files, and emerging author identifier approaches in related domains (ISNI and Orcid). This type of merged environment should also encourage the emergence of linked data approaches, where shared linkable resources emerge for common entities. Rather than repeating data in multiple places, with different structure, it makes sense to link to common reference points. VIAF or Orcid provide examples here.

The determination of similarity and difference as data is clustered across multiple streams becomes more difficult, and it makes it desirable to have firmer agreements about those aspects of the metadata which help to determine identity and relationship. Examples include relating open access material to published versions, clustering digital copies and a print original in the case of digitization, combining metadata for e-books in multiple packages, and so on.

The focus of these systems has been on search of collections. One can see some other possible directions. Here are three.

I discussed institutional and personal curation environments earlier: resource guides, reading lists, social reading sites, citation managers, faculty profiles, and so on. These add a particular context to bibliographic data, where this is a research or learning task, a personal or professional interest, or something else. They can frame the data, which is an important aspect of discovery. Library resources sit to one side of these at the moment, although it would be beneficial to be able to easily provide data to them and to be linked to by them.

Second, library users are interested in other things than collections: library services or expertise for example. We are now seeing an extension of the discovery ambition of libraries to cover "full library" discovery where services, staff profiles and expertise, or other aspects of library provision, are made discoverable alongside, and in the same search environment, as the collections.

The University of Michigan site is a good example. It works well to project the library on the web as a unified service. A central part of this is the integrated search over collections, library website, LibGuides and library staff profiles. The return of relevant subject specialists which match the query in a separate results pane is particularly interesting. Library websites have tended to be somewhat anonymous, or neutral, however if libraries wish to be seen as expert, then their expertise must be visible. The objective here is to answer questions people may have about services, people, and so on, when they come to the library website, not only about items they might find in the collection.11

Third, some libraries are investing in additional local integration layers, which may allow customization to particular institutional interests. Look at the community of Blacklight users for example. Here, a local unifying layer may pull in results from a discovery layer product, a catalog, local databases, the library website, or other resources. In this way, the library can more readily control a local experience, add additional resources, and so on. The University of Michigan, for example, currently uses Drupal for this purpose.12 This trend is related to the second I note here, the ambition to move beyond full collection discovery to full library discovery.

10. The Collective Collection: Network-Level Access

In the network environment described above, there is a natural tendency to scale access to the highest supra-institutional level that is convenient so as to make more resources potentially available to a library user. And we do indeed see a growing interest in consortial or national systems which aggregate supply across a group of libraries. This typically is within a "jurisdictional" context, which provides the agreement between libraries: the University of California system, a consortium such as the Orbis Cascade alliance, a public regional or national system such as Bibsys, the German regional union catalogs, Abes in France, and so on. The level of integration within such systems is growing, so that it is becoming easier to discover, request and have delivered an item of interest. At another level, one role Worldcat plays is as a union of union catalogs, and it allows libraries to "plug into" a wider network of provision. This aggregation of supply makes sense in a network environment and is likely to continue. Libraries then have to make choices about what levels of access to present: local through the catalog, "group" through a union catalog of some sort (e.g., OhioLink across Ohio libraries), and potentially Worldcat or some other resource at a global level.

11. The Collective Collection: Managing Down Print

The catalog is intimately bound up with the "purchased" collection, historically a largely "print" collection (together with maps, CDs, DVDs, etc.). As the importance of the digital has increased, we have begun to see an institutional interest in managing down the low-use print collection. There are various drivers here: the demands on space, the emergence of a digital corpus of books, the cost of managing a resource that releases progressively less value in research and learning. Libraries are increasingly interested in configuring their spaces around the user experience rather than around print collections. Print runs of journals have been an early focus, but interest is extending to books also. In summary, we might say that the opportunity costs of managing large print collections locally are becoming more apparent.

At the same time we are seeing that system-wide coordination of print materials is desirable as libraries begin to retire collections — to offsite storage or removing them altogether. I believe we are moving to a situation where network-level management of the collective print collection becomes the norm, but it will take some years for service, policy and infrastructure frameworks to be worked out and evolution will be uneven. The network may be at the level of a consortium, a state or region, or a country. At the moment, this trend is manifesting itself in a variety of local or group mass storage initiatives, as well as in several regional and national initiatives. Think of WEST (the Western Regional Storage Trust) in the US, for example, or the UK Research Reserve in the UK.

Each of these discussions notes the importance of data: to make sensible decisions you need to have good intelligence about the collective collection of which individual libraries are part. Holdings and circulation data, especially, come to mind. It will become important to know how many copies of an item are in the system, or how heavily used a copy is. It will be important to be able to tie together different versions of an item, different editions, for example, or digital copies and originals. It may also become necessary to record additional data, retention commitments, for example. Libraries have traditionally not shared information at the copy level, however, this becomes more important in this context.

As can be seen, the move to shared responsibility for print raises interesting service and policy issues, as well as very practical management issues. One aspect of this is thinking about our bibliographic data at the aggregate level more, and developing it in the direction which will support the above requirements across the system as a whole. It is likely that union catalogs will have an important role here.

12. Moving Knowledge Organization to the Network Level (and Linked Data)

"Knowledge organization" seems a slightly quaint term now, but we don't have a better in general use. The catalog has been a knowledge organization tool. When an item is added, the goal is that it is related to the network of knowledge that is represented in the catalog. This is achieved through collocation and cross reference, notably with reference to authors, subjects and works. In practice this has worked variably well.

In parallel with bibliographic data, the library community, notably national libraries, have developed "authorities" for authors and subjects to facilitate this structure. From our current vantage point, I think we can see three stages in the development of these tools. In the first, subject and name authorities provide lists from which values for relevant fields can be chosen. Examples are LCSH, Dewey, and the Library of Congress Name Authority File. These provide some structuring devices for local catalogs, but those systems do not exploit the full structure of the authority systems from which they are taken. Think of what is done, or not done, with classification for example. The classification system may not be used to provide interesting navigation options in the local system, and more than likely is not connected back to the fuller structure of the source scheme.

The second stage is that these authority systems are being considered as resources in themselves, and not just as sources of controlled values for bibliographic description. So, we are seeing the Library of Congress, for example, making LCSH and the Name Authority File available as linked data. OCLC is working with a group of national libraries to harmonize name authority files and make them available as an integrated resource in the VIAF service.

In a third stage, as these network resources become more richly linkable, knowledge organization moves to the network level as local systems link to network authorities, exploiting the navigation opportunities they allow. Of course, alongside this, they may also link to, or draw data from, other navigational, contextual or structuring resources such as DBpedia or Geonames. Important reference points will emerge on the network.

Much of the library linked data discussion has been about making local data available in different ways. Perhaps as interesting as this is the discussion about what key resources libraries will want to link to, and how they might be sustained. An important question for national libraries and others who have systems developed in the first phase above is how to move into the web-scale phase three.13 The relationship between the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek and Wikipedia in Germany is an interesting example here.14

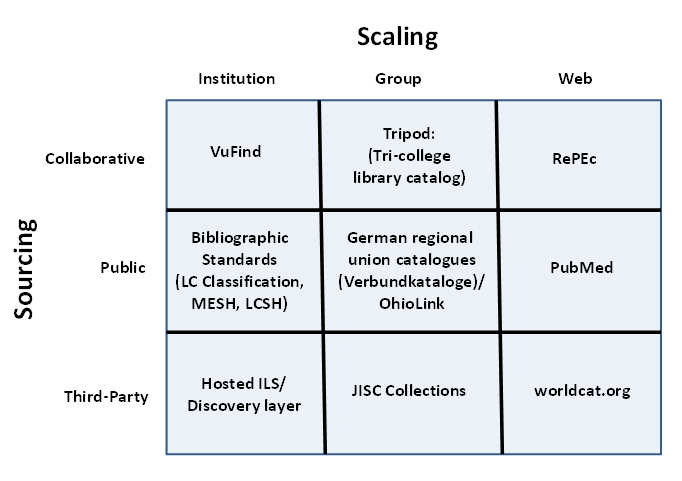

13. Sourcing and scaling

One of the major issues facing libraries as the network reconfigures processes is how appropriately to source and scale activities. An activity might be entirely local, where a locally developed application is offered to a local community. However, this is now rare. It is increasingly common to externalize activity to other providers. In this context, sourcing and scaling provide interesting dimensions to consider options.

Scaling refers to the level at which something is done. Consider three levels:

- Institution-scale. Activity is managed within an institution with a local target audience. For our purposes here think of the local catalog.

- Group-scale. Activity is managed within a supra-institutional domain whether this is a region, a consortium, or a state or a country. The audience is correspondingly grouped. In educational terms think of the activities of JISC in the UK or SurfNet in the Netherlands. In library terms think of the HathiTrust, or of Georgia Pines, or of OhioLink. For our purposes here think of union and group catalogs: the German regional systems (verbundkatalogen), COPAC in the UK, Libris in Sweden, Rero in Switzerland, OhioLink, Trove in Austrlia and so on.

- Web-scale. Activity is managed at the network level where we are now used to services like Amazon, Flickr, Google and YouTube providing e-commerce, collection, discovery and other functions. Here, the audience is potentially all web users. For our purposes here think of Amazon, GoodReads, Google Book Search, or, in library terms, Worldcat.

As I discussed above, we have seen more activity move to higher places in the network. There is both a trend towards more group approaches, and towards using the web-scale services. Again, think of knowledge-base data in Google Scholar, for example, or links to special collections materials added to Wikipedia.

The other dimension is a sourcing one. Again, consider three possible ways in which a product or service might be sourced outside the institution:

- Collaborative. Activity is developed in concert with partners (e.g., purchasing consortium, shared offsite storage, open source software).

- Public. This is common in those jurisdictions where library infrastructure is provided as part of educational or cultural public infrastructure. Think for example of union catalog activity in various countries.

- Third party. Activity is secured from a third party provider. A third party might be a commercial or not for profit supplier.

Of course, there is a lot of overlap between these cells. A publicly supported service like OhioLink, for example, has a strong collaborative component. As the network reduces transaction costs, it is now simpler to externalize in this way. The reduced cost and effort of collaboration or of transacting with third parties for services has made these approaches more attractive and feasible. There are also scale advantages. One aspect of moving services to the cloud is the opportunity to reconfigure them. For example, within agreed policy contexts, there will be greater opportunities for sharing and aggregation of transaction or crowdsourced data in group or web-scale solutions.

Libraries face interesting choices about sourcing — local, commercial, collaborative, public — as they look at how to achieve goals, and as shared approaches become more crucial as resources are stretched. At the same time, decisions about scale or level of operation — personal, local, consortial, national, global — have become as important as particular discussions of functionality or sourcing.

Library approaches to scaling and sourcing will be interesting for several years to come as questions about focus and value are central. In general it is likely that infrastructure (in the form of collections or systems) will increasingly be sourced collaboratively or with third parties, while libraries focus on deeper engagement with the needs of their users.

Coda

Libraries and Discovery: Futures?

I have reviewed a variety of trends. I conclude briefly with some broad brush suggestions about how matters will evolve in the next few years, acknowledging that such speculation is invariably ill-advised.

- Discovery has scaled to the network level. Although the players may change, this trend seems clear. Constraining the discovery process by institutional subscription or database boundary does not fit well with how people use the network. General discovery happens in Google or Wikipedia. And there is a variety of niches. Amazon, Google Books, Hathi Trust or Goodreads for example. arXiv, repec, or SSRN. PubMed Central. And so on. These services benefit in various ways from scale, and mobilize the data left by users — consciously in the form of recommendations, reviews and ratings or unconsciously in the form of transaction data — to drive their services. Within the library arena, several providers are creating "discovery layers," centralized indexes of scholarly material to which libraries are subscribing, and to which they are adding their own local resources. In some cases, libraries are providing additional local customization of this material. While this landscape will invariably change, and providers evolve or disappear, this shift seems set to continue.

- Personal and institutional curation services are now also central to reading and research behaviors, and will also evolve. These include citation management sites, sometimes as part of more general research workflow tools (e.g., Mendeley, Refworks), social reading/cataloging/clipping sites (e.g., Goodreads, LibraryThing, Small Demons, Findings), and resource guides (e.g., Libguides) or reading lists. This is in addition to a range of other support services for reading or research. Think for example of how book clubs or reading groups are supported in various ad hoc ways (this seems like an area where network based services or support will emerge). These services create personal value (they get a job done) as well as often having creating network value (they mobilize shared experiences). They put the management of bibliographic data into personal workflows, and the resulting pedagogical, research or personal framing provides important contextual data which can be mobilized to improve the service (think of Mendeley's "scrobbling," for example). Research workflow tools like Mendeley and social reading sites like Goodreads are important in another way: they allow their users to develop personal libraries connected to network level reservoirs of data and social services.

- This means that library services may focus differently. Here are several ways in which that will happen.

- Location and fulfillment. If "discovery happens elsewhere" it is important for the library to be able to provide its users with location and fulfillment services which somehow connect to that discovery experience. Typically this will involve some form of "switch" between a discovery experience and the location/fulfillment service. Think of configuring Mendeley or Google Scholar with resolver information, or how Google Books uses Worldcat and other union catalogs to provide a "find in a library" link. Some other approaches were discussed above, and it is likely that they will become more routine over time as these "switch" services mature.

- Disclosure. Libraries are recognizing that the presence of institutional resources — digitized materials, research and learning materials, and so on — needs to be promoted. Unless it is particularly significant or central, an institutional resource is unlikely to have strong gravitational attraction. For this reason search engine optimization, syndication of metadata to relevant hub sites, selective adding of links to Wikipedia, and other approaches are becoming of more interest.15 Libraries will have to more actively promote the broad discoverability of institutional resources.

- Consortial or group approaches become more common. As activity in general moves "up" in the network, and repetitive work gets moved into shared services, many libraries seek collaboration around discovery activity at a broader level. The emergence of consortial or group discovery environments is a growing trend.

- Particularization. Some libraries will want to invest in how a variety of local discovery experiences are presented, particularizing general resources to local conditions or aligning them with specific local approaches. The University of Michigan provides an example,16 as do those libraries experimenting with Blacklight.17 It will be interesting to see if the software layer supporting this desire becomes more sophisticated.

- Research advice and reputation management. Researchers and universities are increasingly interested in having their research results and expertise discovered by others. There is a growing interest in research analytics supported by tools from Thompson Reuters and Elsevier, as well as by emerging alternative measures. This means that in addition to supporting disclosure of research outputs, and expertise, there is an opportunity for the library to provide advice and support to the university as it seeks to maximize impact and visibility in a network environment.18

- Knowledge organization will move to the network level. The collective investment that libraries have made in structured data about people, places and things is not now mobilized effectively in the web environment. The cataloguing model is now geared around the local catalog. What is likely to emerge is that authorities, subject schemes, and other data will become network level resources to which data creators link. These in turn can link to Wikipedia or other resources, or be linked to by those other resources. This of course raises questions about sustainability and construction. A purely national model no longer makes sense. The Virtual International Authority File may provide a model here.

- This piece makes extensive use of blog entries from Lorcan Dempsey's Weblog. An earlier article also discusses the catalog: Lorcan Dempsey, "The Library Catalog in the New Discovery Environment: Some Thoughts," Ariadne 48. July 29, 2006. It is interesting how much has changed in the interim.

- This article is a slightly amended version of a contribution of the same name to Sally Chambers, ed., Catalogue 2.0: The Ultimate User Experience (London: Facet Publishing, 2013).

- Lynn Silipigni Connaway, Timothy J. Dickey, and Marie L. Radford, "'If It Is Too Inconvenient, I'm Not Going After It': Convenience as a Critical Factor in Information-Seeking Behaviors," Library and Information Science Research 33 (2011): 179–190.

- Roger C. Schonfeld and Ross Housewright, Faculty Survey 2009: Key Insights for Libraries, Publishers, and Societies (New York: Ithaka S+R, 2010).

- Lorcan Dempsey, "Always On: Libraries in a World of Permanent Connectivity," First Monday 14, no. 1. 5 (January 2009).

- See "Some Thoughts about Egos, Objects, and Social Networks ....," Lorcan Dempsey's Weblog, April 6, 2008.

- This phrase was introduced by Tito Sierra.

- For examples, see Cody Hanson et al., Discoverability Phase 2 Final Report (University of Minnesota, 2011).

- See "Outside-In And Inside-Out," Lorcan Dempsey's Weblog, January 11, 2010.

- See http://trove.nla.gov.au/.

- I discuss the redevelopment of the Stanford University Libraries website in this context on my blog. See "Two Things Prompted by a New Website: Library Space as a Service and Full Library Discovery," Lorcan Dempsey's Weblog, August 31, 2012.

- Ken Varnum, "Don't Go There! Providing Services Locally, Not at a Vendor's Site" (presentation posted on Slideshare, May 2012).

- See "Making Things of Interest Discoverable, Referencable, Relatable, ...," Lorcan Dempsey's Weblog, June 10, 2012.

- Christel Hengel and Barbara Pfeifer, "Kooperation der Personennamendatei (PND) mit Wikipedia," in Dialog mit Bibliotheken 17, no. 3 (2005): 18–24.

- See Hanson et al. for a discussion of approaches.

- See, for example, Ken Varnum's discussion of design choices at the University of Michigan in his presentation at the annual Charleston conference, "Keeping Discovery in the Library" (November 2–5, 2011).

- See examples of libraries using Blacklight.

- I have not discussed the growing interest in disclosing and discovering expertise through profile pages, research networks, and so on.

© 2012 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.