Key Takeaways

- Programs shuttling students, faculty, and staff to foreign destinations challenge university IT departments especially, in that foreign locations and governments can test established IT policies and procedures.

- In particular, the “Great Firewall of China” can pose an unpredictable and undocumented hindrance to travelers.

- In addition to technical challenges, legal issues affect the transport of technology and the use of encryption in foreign locations, making it important to establish best practices for information technology use on foreign soil.

- Mobile computing devices are frequently lost or stolen in transit, requiring IT departments to have contingency plans available.

The world is a book, and he who doesn’t travel only reads one page.

Global programs in higher education continue to grow. At the McIntire School of Commerce, global academic programs have grown to include travel to over 30 countries on six continents. These year-round programs shuttling students, faculty, and staff to foreign destinations represent impressive feats of logistics and coordination, and university IT departments face a particular challenge, in that foreign locations and governments can test established IT policies and procedures.

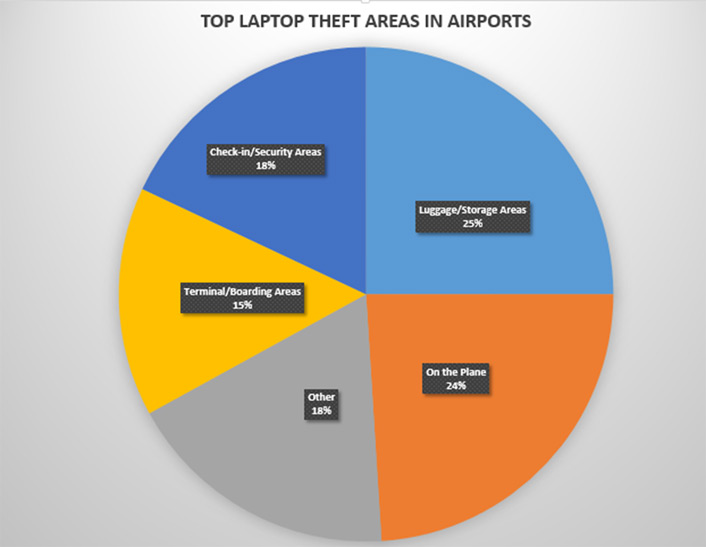

Loss and theft of university-owned and personal devices is all too prevalent in strange and sometimes unsecure environments. Devices will go missing, usually at the least convenient time. A report commissioned by Intel found that more than three-quarters of laptop losses occurred when the device was off-site or in transit.

Sometimes even a well-designed information security policy can wilt under foreign systems. University policies are clear regarding how and where student documents can be stored and transmitted, but these policies become less effective when secure network access is not available, as often occurs in remote and less developed countries. In particular, the “Great Firewall of China” can pose an unpredictable and undocumented hindrance to travelers.

On a recent student trip to China, program coordinators found connections to the McIntire School’s VPN blocked by the Chinese state-run telecoms, meaning they could not access sensitive student data needed for the program. Administrators had to scramble for alternative access methods that complied with established policies (or ask for policy exceptions) and did not threaten data security. The program coordinators had “done everything right” — keeping sensitive data on the school’s servers, not on their local devices, and planning to access it via an encrypted VPN. Yet, sometimes these best-practice scenarios have to be adjusted “on the fly.” Academic institutions often need a bit more flexibility than corporate travelers, particularly when traveling in Asia. Technical solutions that worked on the institution’s last trip to a particular country aren’t guaranteed to work on the next trip.

Sometimes technical issues can affect the curriculum. On another global experience program exploring market insights in China, students discovered that WordPress, their assigned blogging platform for daily trip updates, was completely inaccessible — again, blocked by the “Great Firewall.” Flexible faculty on two continents had to work through alternative methods while the program was underway.

In addition to technical challenges, a number of legal issues affect the transport of technology and the use of encryption in foreign locations. As universities expand their global reach, it is important to carefully establish best practices for information technology use on foreign soil.

U.S. Legal Frameworks and Impacts

With more exotic travel emerging to countries not normally visited by large groups of Americans, it is important to research the legal ramifications of travelling with technology. When Americans travel abroad, the United States Department of Commerce considers physical materials, equipment, data, or software possessed by the traveler to be “exported” from the US to the traveler’s final destination, as well as any intermediate destinations (airport layover, etc.). So what technology can a traveler legally take to a foreign country?

Exemptions from the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) allow the transport of technology items to most foreign countries without a specific license from the U.S. Department of Commerce. The “TMP” exemption covers organizationally owned devices, and the “BAG” exemption covers traveler-owned personal devices. Both exemptions have a similar set of conditions:

- The traveler must spend no more than 12 months outside the United States.

- Items must remain under the “effective control of the traveler” at all times.

- “You maintain effective control over an item when you either retain physical possession of the item, or secure the item in such an environment as a hotel safe, a bonded warehouse, or a locked or guarded exhibition facility.” (Code of Federal Regulations, 15 CFR 772.1)

- Cannot be shipped as unaccompanied baggage; i.e., no flash drives or tablets in a checked suitcase.

- No travel to Iran, Syria, Cuba, North Korea, or Sudan; status of Cuba under review.

You should not take with you any of the following without first obtaining specific advice from your university compliance officer or the U.S. Department of Commerce:

- Devices, equipment, or computer software with export restrictions

- Devices, systems, or software designated as classified or specifically designed or modified for military or space applications

Additionally, accessing export-controlled information via a network is also considered exporting data to a foreign country.

Foreign Legal Frameworks and Encrypting Devices

The use of encryption on devices such as laptops and phones has become a fairly standard practice for IT departments to limit the potential impact of device loss or theft. After all, if a properly encrypted device is lost or stolen, the data is not at risk. However, the use of encryption on devices is not necessarily legal in foreign countries.

The use of encryption internationally is covered by the Wassennaar Arrangement. The following countries are members of the agreement, which allows travelers to bring encrypted devices into their nations as long as the traveler does not modify, sell, or distribute the encryption software:

- Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States

The following countries are not fully-participatory in the Wassenaar Agreement and have restrictions on traveling with encrypted devices. Travelers should be cautious when visiting these nations and should strongly consider bringing an unencrypted “throwaway” device instead of their primary computer (see the resources section for up-to-date information). Restrictions on encryption in these countries range from requiring a ministry of foreign affairs permit to carry an encrypted device to outright bans on using encryption technologies.

- Belarus, Burma (Myanmar), Iran, Israel, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Morocco, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the Ukraine

When university personnel travel to or through one of these nations, we recommend that the university seriously consider loaning them unencrypted devices.

Mobile Data

With the prevalence of global-ready phones, many of your students and faculty will be interested in having voice and data access on their mobile devices.

- Only certain phones are compatible; each carrier keeps up-to-date records of which countries it serves.

- Data transfer in foreign countries can be very expensive. It is important to set up applications to use as little data as possible (downloading only message headers, not automatically downloading attachments, etc.).

- The major U.S. telecoms provide tips to their users on managing data usage while overseas: AT&T [http://www.wireless.att.com/learn/en_US/pdf/Travel-Tips.pdf]; Verizon

Global programs present a unique challenge for most universities. In addition to the educational experience, global program coordinators take on the responsibilities of student health and safety while shuttling students across time zones and countries. With the major logistical effort required to transport students around the world for academic pursuits, technology concerns can be an afterthought. By working closely with travel coordinators, IT departments can ensure that all parties are in compliance with operational, security as well as legal requirements as they travel in foreign lands.

Bon voyage!

Recommendations for International Travel

RED recommendations: for travelers visiting extremely sensitive destinations and/or using extremely sensitive data

Before your trip:

- Contact your university’s office of export controls to discuss your trip and appropriate precautions to take with devices and data.

- If traveling to a country which disallows encryption products, remove encryption from your PC or prepare a “loaner” device.

During your trip:

- If you need to share data with fellow faculty/staff from your university, use encrypted flash drives to transfer data back and forth.

- Take a loaner “dumbphone” (no data storage) instead of your smartphone.

- Shut down devices when not in use (do not use sleep or hibernate features).

- Keep your device(s) on your person at all times — remember that hotel safes may be compromised.

After your trip:

- Erase and reformat the hard drive, especially on a loaner device.

- Wipe data from a temporary “dumbphone.”

YELLOW recommendations: for travelers visiting moderately sensitive destinations or using moderately sensitive data.

Before your trip:

- Ensure your device is encrypted (if permitted by the nation to which you are traveling).

- Password-lock auto-encrypts iPhones; Android users should manually enable encryption.

- Laptops: Use BitLocker, PGP, or a similar tool for Windows; use FileVault on OS X systems.

- “Sanitize” your laptop to remove any sensitive data.

- A product such as Identity Finder can assist this process.

- Only take data necessary for the specific trip.

- Consider taking a temporary device such as a loaner laptop or prepaid phone.

During your trip:

- When using shared Wi-Fi, stay connected to your university's VPN.

- Do not use “shared” computers at a business center or kiosk, etc.

After your trip:

Consider changing passwords for all services/systems you used from overseas.

GREEN recommendations: baseline security for all travelers, foreign or domestic

Before your trip:

- Ensure data is backed up on a server, drive, or other device NOT making the trip.

- Ensure your PC is patched and the antivirus software updated.

- Disable Bluetooth and Wi-Fi on your devices, and only turn them on when in use.

- Notify IT staff of travel plans and locations; IT staff should strongly consider readying spare equipment for delivery in an emergency.

During your trip:

- Assume your data on any wireless network can be monitored, and act accordingly. Use a VPN whenever possible, especially while on public networks and/or when accessing sensitive data.

- NEVER let anyone else borrow or use your devices.

- Do not borrow any devices (e.g. a USB drive) for use on your computer.

- Do not install any software on your PC.

- Be aware of “shoulder surfers” — anyone physically monitoring the use of your device.

- Keep your devices under your physical control or secured in a proper location when they are not. Never check devices or storage devices in luggage.

After your trip:

Perform a full virus and malware scan

Resources

- Bert-Jaap Koops home page, Crypto Law Survey, provides travel tips and tools, with a focus on global regulations on cryptography.

- Princeton University, Office of Information Technology, Encryption and International Travel answers common questions.

- University of Georgia, Office of the Vice President for Research, Export Control, International Travel answers three key questions.

Bryan Lewis is the director of Client Services at the McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia. Lewis is a CISSP and lecturer in information and cloud security.

Eric Rzeszut is help desk manager at the McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia, and was previously an IT manager at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. A CISSP with nearly two decades of information technology and information security experience, he is co-author of the book 10 Don’ts on Your Digital Devices, a guide to data security and digital privacy for nontechnical users published by APress in October 2014.

© 2015 Bryan Lewis and Eric Rzeszut. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.