Key Takeaways

- Suboptimal student performance in lab-based statistics classes prompted a change in pedagogy to increase student engagement in class through active learning.

- Rather than using clickers, students learned how to use Google Forms in class to answer questions alone or in small working groups.

- In-class discussion of the answers focuses on clearing up misconceptions and steering students to a higher level of understanding.

- The increased interactivity, although it reduced class time to cover the material, yielded longer periods of sustained attention and a perception of improved performance among students.

I teach business statistics at a small liberal arts college in the southeastern United States. Over several semesters, I began to see a recurring pattern of three interrelated problems among students in my computer lab–based classes:

- Students were having difficulty completing their homework assignments on time, which probably also resulted in poorer performance on tests. Certainly a range of factors contributed to their difficulty, but it seemed that many students either did not know how to do the homework problems or simply could not remember how when they sat down to work on homework assignments.

- Many students who did not understand the materials covered in class did not ask questions for clarification. Among those students who became confused during class, the third problem often appeared as well.

- Many students used computers in class for activities unrelated to the lessons being taught. They surfed to websites for social networking, news, games, and so forth, which is not uncommon in classes held in a computer lab.

For some time, I blamed the first two problems on the third. I considered blocking students' Internet access in the lab or teaching the class in a regular classroom without student workstations. I realized, however, that the former approach would simply eliminate one possible distraction for students. They could use smartphones instead, for instance, to surf the web or send e-mail. The latter solution was also unattractive because in a regular classroom, we could not take advantage of computer applications, such as MS Excel, during class meetings. For many subjects, these applications enable the instructor and students to focus on the important concepts — in this case, statistical reasoning and interpretation of analysis outputs of data sets.

Student Engagement as a Solution

After struggling for several semesters to solve these problems, I concluded that I should cultivate stronger student engagement in class to help them understand the material better. This meant modifying class sessions to use more active-learning methods. Rather than just passive listening in class, students would engage in activities such as problem solving, exercising higher order thinking, and so on. To accomplish this, I decided to use technology tools to support my pedagogical changes.

Classroom response systems (CRSs), commonly called clicker systems, are a popular technology for promoting active learning. A CRS facilitates interactive class sessions by allowing faculty to ask questions to which students respond during class. Responses are tabulated, indicating how well the students understand the material and allowing the instructor to provide immediate feedback and ensure comprehension of important points. Most clickers only permit multiple-choice questions, however, limiting the options for active engagement.

Beyond Clickers

Google Forms is a component of Google Docs, which is a free, web-based suite of tools for managing various kinds of files including text documents, spreadsheets, and presentations. With Google Forms, an instructor (or any user) can create a set of questions and invite students (participants) to respond to those questions, either through e-mail or on a web page. The application supports various types of questions: text, paragraph, multiple-choice, lists, check boxes, scale, and grid. Response types include entering free-form text, selecting from an instructor-defined scale, or choosing from a restricted set of options. In Google Docs, a form can stand alone or be used to collect responses that feed into a spreadsheet, which can then be used to manipulate the data gathered. Google Forms will tally responses instantly — responses appear in a spreadsheet on a screen at the front of the room as soon as students submit them.

To see how Google Forms works, see the short video:

Google Forms in a Statistics Class

In my statistics course, I usually begin each class session with a lecture of 10 to 15 minutes, during which I briefly cover main concepts of that day's lesson and some example questions. For instance, one class meeting addresses the definitions and concepts of mean, median, and mode. Then, using textbook examples, I explain how to calculate such measures using a spreadsheet application, in this case MS Excel. However, I do not explain everything in detail in the lecture.

Then I ask students to:

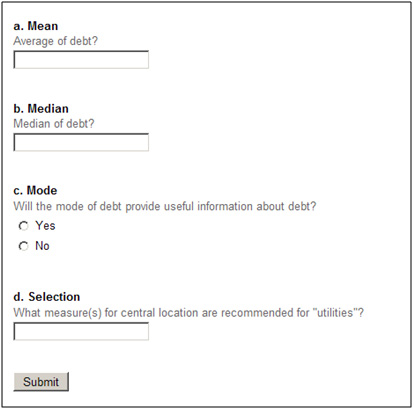

- Go to a web page containing relevant Google Forms questions for the lecture just given (see Figure 1 for an example set of questions).

- Work on the questions, either individually or with classmates as a group.

- Submit their answers after a few minutes.

During this activity, students are actively engaged with the content, especially because, as noted, I have not fully spelled out how to accurately answer the questions. As a result, students need to think creatively, ask questions of me or their group partners, consult a textbook, or otherwise work out for themselves how best to respond to the questions.

Figure 1. Example Questions in Google Forms

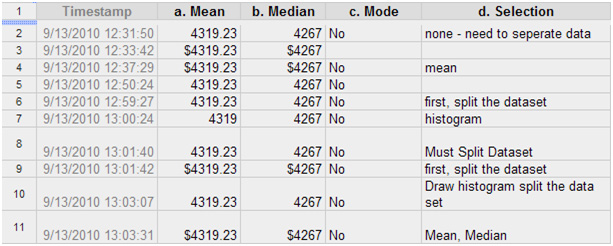

Once students complete their responses, I show their answers on the screen and discuss them with the students. I spend little time discussing correct answers, focusing instead on questions with multiple answers and consulting students on which answer they believe is correct. Then I expand on their explanations until I believe they comprehend the concepts. In the example shown in Figure 1, students did well on the first three questions (see Figure 2). I complimented them on their responses for these questions and spent very little time discussing them. On the contrary, the fourth question elicited a variety of answers. I polled students on which answer seemed to be the correct one and asked them to explain or defend their answers. I expanded on their explanations until I felt comfortable that they had a clear understanding of the concept, and then I closed the discussion.

Figure 2. Answers to the Questions in Figure 1

After discussion of the answers, I move to another topic and start the cycle again. That is, I lecture on new topics for 10 to 15 minutes each, ask students to work on questions about those areas, and discuss the answers. I can usually complete two or three cycles in a 75-minute class.

Student Opinions of Google Forms

To evaluate students' perceptions of the effectiveness of Google Forms, in June 2010 I conducted a survey of the 62 students who had taken my statistics course (39 in two sections in spring 2010 and 23 in one section in summer 2010). I developed the survey instrument based on a study conducted by Margie Martyn1 that surveyed students about their perception of the usefulness of a CRS in class. The questionnaire included eight questions: seven 5-point Likert-scale questions (which used a scale of 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, 5 = strongly agree), plus one open-ended question for which students could enter free-form text responses. A total of 29 undergraduate students who took my classes participated voluntarily in the survey.

As shown by the results in Table 1, students had a favorable reaction to the use of Google Forms. The relatively low score for question 5 does not necessarily indicate a limitation of Google Forms in promoting student interaction; rather, that score probably results from how Google Forms questions were used in my class — most questions were answered individually, even though I allowed students to talk each other.

Table 1. Survey Results of the Perceived Effectiveness of Google Forms

Question | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 1. Participation with Google Forms improved my grade in the course. | 3.9 | 0.7 |

| 2. Participation with Google Forms improved my understanding of the subject content. | 4.1 | 0.7 |

| 3. Participation with Google Forms increased my concentration levels in lectures. | 4.3 | 0.7 |

| 4. Participation with Google Forms increased my interaction with the instructor. | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| 5. Participation with Google Forms increased my interaction with other students. | 3.6 | 1.0 |

| 6. I enjoyed participation with Google Forms. | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| 7. I would recommend using Google Forms again in this course. | 4.5 | 0.7 |

Students' written comments reflect similar reactions. For example, one student commented:

"I enjoyed learning the material through the use of Google Forms; also, it really helped, I think, in being able to focus more on topics for which most of the class needed more information."

Students also commonly appreciated ease of access to Google Forms (it was available on the web). They could go back into a database to review the questions and answers from the class sessions while studying. To illustrate, another student commented:

"The best part of this technology was that it was available from home or school or any remote place."

Upsides, Downsides, and Recommendations

Compared to a typical CRS, advantages of Google Forms include lower cost (free) and support for multiple formats for questions. Further, Google Forms can be tightly integrated with other Google products, such as Google Sites, where my class website is hosted (see https://sites.google.com/site/gfexamples/home). Google Forms can be used in any course as long as the students have access to computers — they can use laptops or smartphones. Therefore, instructors may use Google Forms questions in online courses, especially real-time (or synchronous) ones, with the advantage of immediate tallying of all the answers, including free-form text.

One of the primary benefits of using Google Forms is its ability to help instructors assess — in real time — how well students understand learning materials and to uncover student misconceptions, which helps instructors steer students to higher-level understanding. For probing how students think, I often use both short- and long-answer questions (such as those shown in Figure 1) because this combination of question types is especially effective at evaluating learning.

Another benefit I have observed in my classes is increased interactivity between students and between the instructor and students. This can result in longer periods of sustained attention to the material and in livelier class sessions. On a form, an instructor can include a question that allows students to enter a unique identifier for each question set so they can spot their answers during discussion (see https://sites.google.com/site/gfexamples/use-of-identifier for an example). Inevitably, some students use humorous identifiers, which livens up the class. Alternatively, an instructor could ask students to use their names. In this case, Google Forms questions can be used as graded in-class activities or as a tool for checking attendance.

Similar to a CRS, one downside of using Google Forms can be less time to cover course material because class time is used to respond to Google Forms questions and discuss students' answers. In my experience, however, the tradeoff is definitely worthwhile. Because a large portion of class time is devoted to Google Forms questions, the instructor needs to write good questions. Criteria of good Google Forms questions, especially multiple-choice questions, are similar to those of good CRS questions suggested in the literature.2 Alternatively, by using text-response questions, an instructor can ask students to submit their own questions based on what they learned in that day's class. The class can then spend some time discussing those questions, some of which might even be used on tests. One caution in using short- or long-answer questions (including the identifier) is that student responses can be completely unrelated to the class activity, or even inappropriate. Even though this has happened rarely in my classes, it is nevertheless one possible shortcoming of using text-response questions.

Another potential downside of Google Forms is that it remains an evolving application. The interface might change, and it currently does not include certain features that would be particularly useful, such as the ability to reset a form and clear previous responses. As it works today, an instructor must go through several steps to delete answers from a form to use the same form in multiple classes or over several semesters. That said, this kind of functionality could be implemented relatively easily, and new features are indeed being added.

Concluding Thoughts

In my business statistics courses, adding Google Forms to the learning activities has resulted in more time on task for students and more engagement with other students and me, and with the course material. Students seem to spend less time distracted by nonacademic websites and personal activities, and I see more participation in class among those students who formerly kept quiet, even when they were confused about the material. More students complete their homework assignments on time, and test scores have also improved for many students. Although other approaches might have produced positive results as well, this web-based tool helped me solve, at least partially, the three problems interfering with my students' learning.

- Margie Martyn, "Clickers in the Classroom: An Active Learning Approach," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 2 (April–June 2007), pp. 71–74.

- Ian Beatty, "Transforming Student Learning with Classroom Communication Systems," Research Bulletin 3 (2004), EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research; and Ian D. Beatty, William J. Gerace, William J. Leonard, and Robert J. Dufresne, "Designing Effective Questions for Classroom Response System Teaching," American Journal of Physics, vol. 74, no. 1 (January 2006), pp. 31–39.

© 2011 Dong-gook Kim. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.