Key Takeaways

- Formative assessment can foster student retention and success by engaging students in their own learning process and helping instructors adjust to learners' needs in real time.

- Classroom assessment techniques (CATs) are a powerful formative assessment tool that can give students a sense of learning community even in large classes.

- Using clickers or other types of learner response systems enables instructors to conduct many CATs quickly and easily.

- Employing CATs with clickers as part of an ongoing course improvement cycle contributes to a faculty member's instructional development and can provide valuable teaching data for promotion and tenure.

Formative assessment can play a critical role in fostering student success by engaging students in their own learning process, focusing their attention on what really matters, and helping instructors adjust to student learning needs in real time.1 Classroom assessment techniques (better known as "CATs" and pronounced "cats") are a powerful formative assessment tool,2 and many CATs can be conducted quickly and easily in the classroom with clickers or other types of learner response systems.

Formative Assessment with Clickers

Educational psychologists have long emphasized the value of formative assessment in the learning process to provide students with constructive feedback and help them develop metacognitive skills that improve their ability to effectively apply learning strategies.3 Research has shown that formative assessment is particularly helpful to low-achieving students and students with learning disabilities.4 Despite the well-documented value of formative assessment, traditional classroom teaching methods often emphasize information flow only from instructor to students, except at exam time when it is usually too late for instructors to help students who are struggling. By design, clickers — and a growing array of other learner response systems — make data about student learning available to instructors on a just-in-time basis that is ideal for formative assessment.5 While some faculty members use clickers only to take attendance or administer self-grading quizzes, many others appreciate their value as a tool to monitor student learning and to respond to student needs.

CATs are a well-developed set of formative assessment processes for collecting classroom data to support continuous course improvement. CATs are highly regarded by teaching and learning specialists, but might be less familiar to those who have come into a faculty development role through involvement with instructional technology. By showcasing CATs as a use for clickers, we hope to make instructional technology staff more aware of the potential value of clickers for formative assessment and also to encourage a more systematic and rigorous approach to using clickers for this purpose. Additionally, we offer suggestions and resources to instructional technology staff for conducting faculty development workshops about using clickers to conduct formative classroom assessments. We assume the reader is already familiar with clickers and is now looking for examples of how to use them in educationally sound ways.6 We hope our ideas and resources will prove helpful to:

- Those looking for faculty development resources to improve teaching and to promote effective uses of clickers at their institutions

- Individual instructors looking for ideas on how to use clickers effectively in the classroom

- Those interested in formative assessment

- Those wishing to document instructional improvement efforts for promotion and tenure

The Need for Sound Clicker Pedagogies

In the past several years, faculty interest in clickers has spread rapidly on our campuses. At the University of Illinois at Chicago, for instance, a recent educational technology survey showed that 14 percent of faculty respondents had used clickers in their courses, while 34 percent would like to use them.7 At the University of Colorado at Boulder, 15 percent of faculty members reported using clickers as of 2008.8 Although the EDUCAUSE Core Data Survey does not capture actual clicker usage, data from 2005 to 2009 indicate a rise in clicker availability in classrooms across U.S. institutions.9 CU–Boulder, in collaboration with the University of British Columbia, has been especially active in developing methods for using clickers to teach in STEM fields and in conducting research concerning students' preferences for how clicker questions are designed and incorporated into the learning process. Faculty members participating in this Science Education Initiative (SEI) have used clickers to carry out peer instruction, an interactive teaching method developed by Harvard physics professor Eric Mazur designed to ensure that students genuinely understand physics concepts,10 and to conduct research on the effectiveness of peer instruction that was published in the prestigious journal Science.11 A study of 615 students in an introductory psychology class at the University of Wisconsin at Madison suggests that clickers might be especially helpful to students who feel unprepared for college.12

Nonetheless, many faculty members still ask for advice on how to use clickers in educationally effective ways. Those requests are welcome because they show that the faculty member cares about learning goals and isn't merely "using technology for technology's sake," which can be ineffective and frustrating for learners. Indeed, for many faculty members, especially those teaching large courses, using clickers may represent a first attempt to break away from traditional lectures, marking an exciting first step in developing greater expertise in teaching and learning. Although faculty sometimes view clickers as a specific, alternative pedagogy (such as peer instruction), we prefer to view them as one tool in the kit of effective instructors and as a "gateway" technology that helps move instructors toward more active, responsive teaching, with and without technology.

Resources for Using Clickers

After faculty have learned how to make clicker slides and are comfortable administering clicker questions in the classroom, they often start to feel their approach is getting repetitive. They then start looking for new ideas to derive increased educational value from clickers. When this happens, we point them to resources that emphasize how to write questions that are more challenging and more likely to provoke discussion, and how to use clicker questions to promote active and collaborative learning, particularly in large classes. Two recent books and their associated websites that do so very well are Douglas Duncan's Clickers in the Classroom13 and the associated SEI Clicker Resources web page, and Derek Bruff's Teaching with Classroom Response Systems14 and his associated blog. Figure 1 shows Bruff teaching a class using clickers.

Figure 1. Derek Bruff Using Clickers in a Math Class

The following audio file is of author Deborah Keyek-Franssen interviewing Bruff:

SEI's collection of videos is especially helpful for showing faculty members how clickers can be incorporated into large and small classrooms. In addition, a number of universities and clicker vendors provide clicker resource websites that serve as clearinghouses for ideas, experiences, tips, and research about clicker use in a variety of academic fields (see "Additional Resources").

Rediscovering a Teaching and Learning Classic

One of the most important benefits of clickers that both Duncan and Bruff discuss is the enhanced ability of the instructor to monitor student learning and to immediately respond to students' needs for clarification or additional practice. This emphasis on monitoring student learning reminded us of an older book that deserves rediscovery as an excellent resource for beginning clicker users, even though it was written long before clickers came into common use in college and university classrooms. Thomas Angelo and K. Patricia Cross's Classroom Assessment Techniques has been popular since 1993, but it originated in 1988 as a publication by the National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning (NCRIPTAL), a large, federally funded project centered at the University of Michigan, to identify and disseminate effective teaching and learning practices for college and university educators. Almost immediately, the book became a classic text in the literature on teaching, learning, and assessment for college teachers.

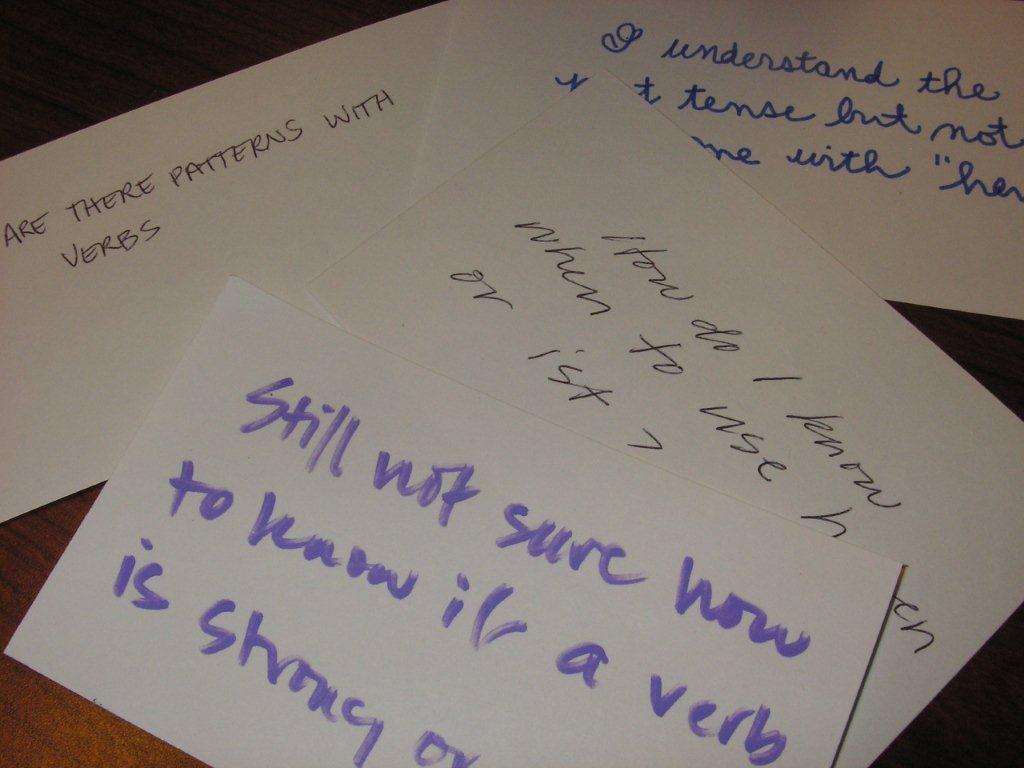

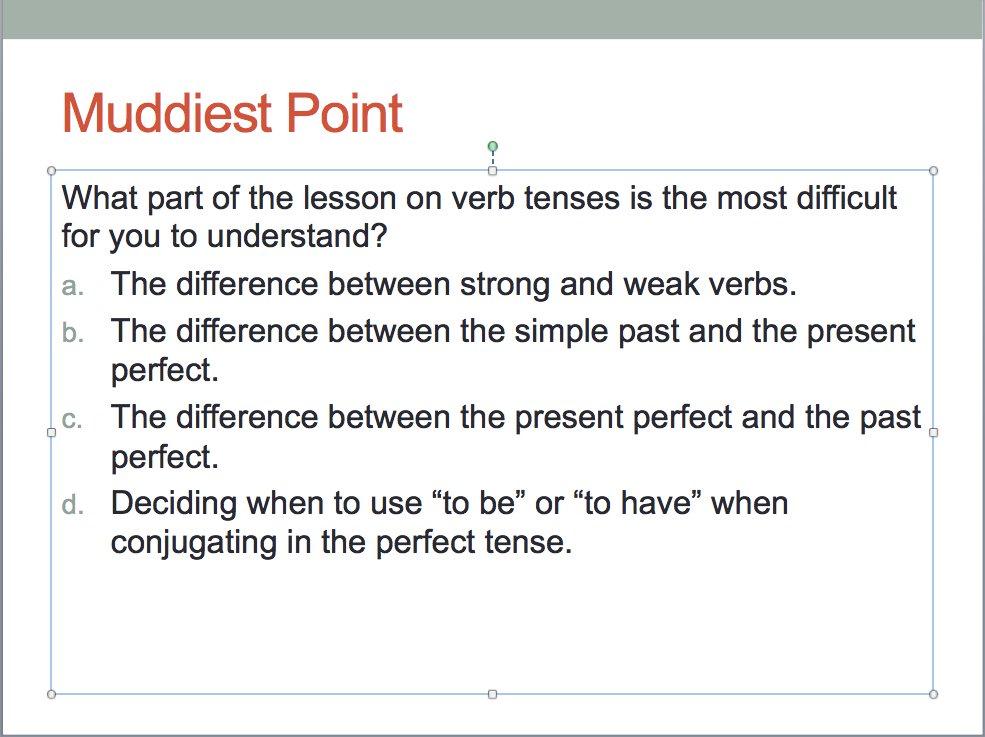

CATs are brief activities to collect classroom data to gauge student understanding or some other aspect of the learning experience. Many faculty members are familiar with some of the most popular CATs, such as the "Minute Paper" and the "Muddiest Point," which traditionally have entailed students writing on index cards or sheets of notebook paper to quickly assess their understanding or confusion about a topic covered by the day's lesson. Usually the instructor collects the papers, reads them after class, and follows up accordingly during the next class session. Figure 2 shows a traditional Muddiest Point CAT, while Figure 3 shows a clicker poll designed for the same purpose — to identify the muddiest point.

Figure 2. Traditional Index Card Survey to Find the Muddiest Point

Figure 3. A Clicker Poll to Find the Muddiest Point

Angelo and Cross provide evidence that faculty members find CATs useful and that feedback from CATs challenges teachers' assumptions.15 They also report evidence for a number of beneficial effects on students that are consistent with various models of student learning and student retention, including that CATs:

- Increase active involvement in learning

- Promote metacognitive development

- Increase cooperation and a sense of the classroom as a "learning community"

- Increase student satisfaction

- May improve course completion rates

The key benefit of CATs is that they allow instructors to make immediate changes to help students succeed in their courses, which not only supports the acquisition of intended learning outcomes but also could improve the odds of course completion for students who encounter difficulties. CATs embed an element of academic support directly into the classroom experience that builds on the well-established principle that feedback is most helpful when provided early and often in the learning process. CATs also allow faculty members to discover and fix problems right away rather than waiting until the next time they teach a course. As a result, students immediately benefit from the feedback provided, and instructors have a chance to make mid-course corrections before students evaluate their teaching at the end of the term.

Indeed, many faculty members who use CATs report improved rapport with students that they believe contributes to improved teaching evaluations. In a course on student assessment that one of us led for community college faculty in the City Colleges of Chicago, participants reported that they particularly valued the increased sense of reciprocity they enjoyed with their students as a result of CATs. In these highly diverse classrooms, CATs helped the instructors better understand their students' range of responses and needs. They also reduced students' anxiety about getting the help they needed to succeed in college, because they could see that their instructors genuinely wanted to know if they were having difficulty and were willing to make changes in response to student feedback.

Faculty development and assessment administrators like CATs because they help instructors gain an appreciation for assessment and learn some basic assessment principles. Faculty often find CATs more appealing than more formal, program-level assessment initiatives because they focus on the instructor's own questions about a class rather than on measures determined by committee or on stock questions that appear on end-of-semester course evaluations.

CATs That Can Be Performed with Clickers

Since clickers are often used to monitor student learning, we decided to conduct an analysis of all 50 CATs in Angelo and Cross's Classroom Assessment Techniques book to determine which CATs can be conducted with clickers. Because clickers require students to select one response from a set of options, we first looked for CATs that called for multiple choice questions or that could easily be transformed into multiple choice questions. This search resulted in a list of 13 CATs that can be conducted with clickers by using Angelo and Cross's original instructions with little or no alteration. Next we carefully considered the remaining CATs to determine which could be adapted for use with clickers to achieve the same or a similar goal, if perhaps through a somewhat different process. This second review resulted in 10 additional CATs, for a total of 23 of the original 50 CATs that can be conducted with clickers. For this second set of 10 CATs, we wrote suggestions for how to adapt each CAT for use with clickers. Our suggestions are surely not the only way to adapt the CATs for clickers, but hopefully will spur thinking about the possibilities. In Classroom Assessment Techniques, Angelo and Cross offered several alternative ways to use most CATs and encouraged faculty to adapt them freely to their own needs and teaching contexts.

Teaching Faculty About CATs with Clickers

Anyone with access to the Classroom Assessment Techniques book can use it to learn about CATs and to find ideas for conducting formative assessments with clickers. However, to make it easier to share our ideas with other faculty members and instructional development staff, we created a handout with a table of the 23 CATs that can be conducted with clickers, as well as a slide presentation with talking points, a complete set of explanatory notes, and suggestions for audience participation. The table and slide presentation are available to download for individual use or for faculty development purposes from the EDUCAUSE Learning Center.16 Although the table is meaningful only when used in conjunction with the Classroom Assessment Techniques book, we have included it in this article for convenience (see "Handout: Classroom Assessment Techniques with Clickers"). An explanation of the table provided at the top of the handout summarizes information in this article. Note that the suggestions for adapting some of the CATs for clickers merely supplement the full instructions found in the Classroom Assessment Techniques book and are not intended as a stand-alone resource. Full instructions would be too lengthy to include in the table and might discourage faculty members from consulting the book, which includes much more information about classroom assessment than we can include here.

How to Use the Table

The first step to using the Classroom Assessment Techniques with Clickerstable is to become familiar with the Classroom Assessment Techniques book. The table is organized in sections found in the book's table of contents. The sections help instructors find CATs that match their assessment purpose, such as "Assessing Prior Knowledge, Recall and Understanding" or "Assessing Skill in Application and Performance." While some CATs assess knowledge or skills, others assess affective responses that may be important to morale and motivation, such as "Assessing Learner Reactions to Teachers and Teaching" or "Assessing Learner Reactions to Class Activities, Assignments, and Materials." The left-hand column of the table lists the CATs, grouped by their assessment purpose, as they were originally organized in Classroom Assessment Techniques. The middle column provides the page number in the book, and the right-hand column offers suggestions for the 10 CATs that require adaptations to clickers. Once an instructor is familiar with the book, the handout can be used to speed the process of finding CATs that lend themselves to clickers.

Getting the Most Out of CATs with Clickers

Faculty members and students benefit most from CATs when they are used to generate class discussion and when they are part of a complete classroom assessment project cycle. Generally speaking, the adaptations required to make some CATs work with clickers also change the techniques from ones in which students generate their own responses to ones in which they choose from predetermined options. Consequently, CATs that require changes to adapt them to clickers tend to be less intellectually challenging than in their original format, just as the level of an examination would tend to move downward in Bloom's Taxonomy if questions were converted from essay or short-answer format to a multiple-choice format. While some of the richness of the original CAT might be lost by the adaptation to clickers, using the clicker portion of the exercise to prompt small group or class discussion is a good way to recapture the higher level intellectual benefits of the original CAT. Furthermore, regardless of how CATs are conducted, Angelo and Cross recommended that data collection be followed by a class debriefing and discussion in order to derive the most benefit. Similarly, many clicker techniques involve class discussion as an essential part of the process, and instructors often marvel at the effect of both CATs and clickers to spur reticent students to speak up in class. Not only does the combination of CATs and discussion help instructors monitor student understanding, it also provides an opportunity to correct misconceptions and give formative feedback to students about how they're doing.

In addition to incorporating discussion into CATs, Angelo and Cross recommended embedding CATs in a complete classroom assessment project cycle. For instructors who typically lecture, using CATs with clickers can be an exciting way to inject new energy into classes and to develop a closer relationship with students, but it can also be an uncomfortable eye-opener to realize that students understand less than expected. The project cycle helps instructors embed formative assessment into a continuous improvement cycle that puts "bad news" to use in a constructive way.

The project cycle starts with identifying an assessable question about a specific lesson or course, and then looking through Classroom Assessment Techniques to find a CAT that matches that need. Collecting and analyzing the data is the next step. Once the instructor has determined what the data mean, it's time to decide what to do with the information. Options might include reviewing a topic in more detail, providing a demonstration of some sort, or offering to hold an additional study session for students who are having difficulty. Conversely, the CAT might confirm that students have a good grasp of the lesson and are ready to move on to the next topic. Next, an essential part of any CAT is debriefing with the class to discuss the findings and explain the steps the faculty member will take to follow up. Finally, as with any good assessment process, the instructor makes changes to improve the course and then collects data again to test the effectiveness of the changes and to plan new changes to keep the improvement cycle going.

The most important reason to embed CATs into a classroom assessment project cycle is that students benefit when formative assessment becomes part of a continuous improvement process focused on their needs and success. A side benefit is that it helps faculty carry out and document their instructional development efforts in a systematic, scholarly way for tenure and promotion. Particularly if a course has weak learning outcomes or teaching evaluations, the very act of articulating a problem and carrying out a plan to address it might persuade a promotion and tenure committee that the instructor shows promise as a teacher. Likewise, even a minimally documented CAT helps ensure that the instructor receives credit for improvements to the course that might not otherwise be visible.

Administering CATs with clickers makes data collection, analysis, and display a great deal easier and quicker than in the days when instructors collected stacks of index cards and then spent the rest of the afternoon tallying up the responses by hand. Certainly, any aid in collecting data about teaching effectiveness is a boon to the junior faculty member trying to juggle new responsibilities while simultaneously documenting them for promotion and tenure.

Final Thoughts

In recent years, few technologies have captured the interest of faculty and students as mutually as clickers. Perhaps something in our evolution has hardwired us to be attracted to little devices with buttons, or to the suspense of wondering how others will respond to a question. Perhaps the anonymity of clickers adds to the appeal. Whatever the reasons, it's important to channel that interest in clickers into uses that improve learning and to help instructors incorporate clickers into the classroom experience as smoothly and successfully as possible. Angelo and Cross worked with over 5,000 faculty members to refine their collection of 50 CATs, keeping only those that were the most effective, easy, and adaptable to varied teaching contexts.

Several faculty members from the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Dentistry have begun to use clickers to conduct CATs and have reported that they are both useful and easy to perform with clickers. One has incorporated "The Muddiest Point" into the evaluation of a new instructional video she produced, and is using the student response data both to improve the video and as part of an analysis she hopes to publish. Her use of clickers and CATs in a complete classroom assessment project cycle to improve her own teaching while also generating publishable research shows how using clickers for formative assessment naturally engages faculty in the scholarship of teaching. As such, faculty development efforts that expose instructors to CATs as an approach to using clickers for formative assessment can help ensure that the needs of learners will guide the use of this rapidly spreading classroom technology.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a presentation by the same title given by the authors at the Annual ELI meeting, January 20, 2010, Austin, TX.

- David J. Nicol and Debra Macfarlane-Dick, "Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice," Studies in Higher Education, vol. 31, no. 2 (2006), pp.199–218.

- Thomas Angelo and K. Patricia Cross, Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993).

- Carol Boston, "The Concept of Formative Assessment," Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, vol. 8, no. 9 (2002).

- Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam, "Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment," Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 80, no. 2 (1998), pp. 139-148.

- Throughout this article we use the word "clickers" as shorthand for any type of learner response system that uses a multiple-choice question format to collect data and that is capable of instant display of item response frequencies, including systems with mobile device capability, and polling functions built into web-based synchronous learning platforms.

- Issues related to the pros and cons of clickers, criteria for their selection, cost and strategies for campus implementation of clicker systems have been addressed by previous authors and are beyond the scope of our discussion. Please see the EDUCAUSE Resource Center for more information on clickers.

- UIC IT Taskforce — Educational Resources Survey, University of Illinois at Chicago (2010, unpublished).

- Deborah Keyek-Franssen and Charlotte Briggs, "Ask Good Questions by Starting with Key Decisions," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4 (October–December, 2008).

- Pam Arroway, Eric Davenport, and Guangning Xu, EDUCAUSE Core Data Survey Fiscal Year 2009 Summary Report (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, October 2010).

- See Eric Mazur, Peer Instruction: A User's Manual (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997); and Catherine H. Crouch and Eric Mazur, "Peer Instruction: Ten Years of Experience and Results," American Journal of Physics, vol. 69 (2001), pp. 970–977.

- Michelle K. Smith, William B. Wood, Wendy K. Adams, Carl Wieman, Jenny K. Knight, Nancy A. Guild, and Tin Tin Su, "Why Peer Discussion Improves Student Performance on In-Class Concept Questions," Science, vol. 323, no. 5910 (January 2009), pp. 122–124.

- Jeff Henriques, "Students Who Feel Unprepared for College Find 'Traditional' Teaching Tools Less Helpful," Teaching and Learning Excellence, January 15, 2009.

- Douglas Duncan, Clickers in the Classroom: How to Enhance Science Teaching Using Classroom Response Systems (San Francisco: Addison Wesley, 2004).

- Derek Bruff, Teaching with Classroom Response Systems: Creating Active Learning Environments (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009).

- Angelo and Cross, Classroom Assessment Techniques, p. 371.

- See Charlotte L. Briggs, "Classroom Assessment Techniques with Clickers Table," and Charlotte L. Briggs and Deborah Keyek-Franssen, "CATs with Clickers," presentation slides with notes,in Charlotte L. Briggs and Deborah Keyek-Franssen, "CATs with Clickers: Using Learner Response Systems for Formative Assessments in the Classroom," a presentation at the Annual ELI meeting, January 20, 2010, Austin, TX.

© 2010 Charlotte L. Briggs and Deborah Keyek-Franssen. The text of this EQ article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.

Handout: Classroom Assessment Techniques with Clickers

Copyright 2009 Charlotte L. Briggs. This table is the intellectual property of the author. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this copyright statement appears on the reproduced materials and notice is given that the copying is by permission of the author. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the author.

The following table lists classroom assessment techniques ("CATs") that can be conducted using clickers. The CATs are from Thomas Angelo and K. Patricia Cross's book Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993).Of Angelo and Cross's original 50 CATs, 13 can be conducted with clickers as written, and 10 more can be conducted with some modifications to the instructions, for a total of 23 CATs that lend themselves to clickers. The left-hand column lists the CATs, grouped by their assessment purpose, as they were originally organized in the Angelo and Cross text. The middle column provides the page number in Angelo and Cross's book, and the right-hand column offers suggestions for adapting CATs where the original instructions cannot be carried out with clickers as written. Generally speaking, the adaptations change the technique from one in which students generate their own responses to one in which they choose from a predetermined set of options. While some of the richness of the original CATs may be lost by some of the adaptations to clickers, using the clicker portion of the exercise to prompt small group or class discussion is a good way to recapture higher level intellectual and expressive benefits.

Classroom Assessment Techniques with Clickers

| Type Technique |

Page |

Adaptation for Clickers* |

| Assessing Prior Knowledge,Recall and Understanding | ||

| Background Knowledge Probe | 121 | |

| Misconception/Preconception Check | 132 | |

| Muddiest Point | 154 | List potential topics on slide and include an "other" option. Ask students to indicate the topic with which they had the most difficulty. If a significant proportion of the class selects "other," probe the class to identify other "muddy" issues. In some cases, it may help to prepare a slide that lists the major topics, and then a second set of slides that list the subtopics for each major topic. |

| Assessing Skill in Analysis and Critical Thinking | ||

| Defining Features Matrix | 164 | Present prompts one-by-one on slides, listing the defining features or categories as response options. Alternatively, use "Yes/No," "True/False," or "Present/Absent" as response options. |

| Pro and Con Grid | 168 | Present one pro or con for the phenomenon of interest and ask students to determine if it is "True/False" or if it "Never/Sometimes/Always" occurs. Alternatively, for a given characteristic or potential outcome, ask students to postulate whether a particular person or group would consider it a pro or a con. |

| Assessing Skill in Synthesisand Creative Thinking | ||

| One-Sentence Summary | 183 | Present a fully composed "WDWWWWHW" statement with a blank space for one of the elements and ask students to select the response option that best fits in the blank. Alternatively, present a statement that contains one or more errors and ask students to identify the element that is incorrect. |

| Approximate Analogies | 193 | |

| Assessing Skill in Problem Solving | ||

| Problem Recognition Tasks | 214 | |

| Assessing Skill in Application andPerformance | ||

| Student-Generated Test Questions | 240 | After reviewing all student-generated test questions to determine class strengths and weaknesses, select a number of questions to present back to the class for review before the examination. Alternatively, break the class into groups and ask each group to prepare a small number of questions to present to the class. Caveat: Constructing clicker questions that are intellectually more advanced than factual recall, while also avoiding ambiguity or "trick questions," may be difficult for students. Students may benefit from some examples of "good questions" and some tips for "what to avoid" when writing questions. |

| Assessing Students' Awareness of Their Attitudes and Values | ||

| Classroom Opinion Polls | 258 | |

| Double Entry Journals | 263 | Present a list of readings and ask students to vote on which was most helpful, interesting, controversial, or some other attribute. Follow up with a class discussion about the highest vote-getter or about their reasons for voting as they did. If more than one reading receives a significant proportion of the votes, consider breaking the class into groups to discuss the different readings. |

| Everyday Ethical Dilemmas | 271 | Allow students to vote on whether a course of action is ethical and then discuss it as a class. Alternatively, if a course provides a framework for analyzing ethical decisions, or if it introduces students to a code of ethics for a particular profession, present a case that includes a potential dilemma and ask students to vote on which ethical concept or criterion most applies to the case. |

| Course-Related Self-Confidence Surveys | 275 | |

| Assessing Students' Self-Awareness as Learners | ||

| Interest/Knowledge/Skills Checklists | 285 | |

| Goal Ranking and Matching | 290 | |

| Self-Assessment of Ways of Learning | 295 | |

| Assessing Course-Related Learning and Study Skills, Strategies, and Behaviors | ||

| Productive Study-Time Logs | 300 | After students have kept study logs for a period of time, ask them questions about their study habits such as How many hours a week do you study for this course?; How often do you discuss course topics outside of class?; On average, how many pages of notes do you write during class?; or Do you multi-task while you study? After students see how their study habits compare to those of classmates, ask them to write some goals for maintaining or changing their habits in the future. |

| Assessing Learner Reactions to Teachers andTeaching | ||

| Teacher-Designed Feedback Forms | 330 | |

| Group Instructional Feedback Technique | 334 | After groups have presented their feedback, use a show of hands to reduce the list to no more than 5 items. Prepare a slide in advance with spaces to type up to 5 response options. Alternatively, prepare a slide with options labeled A through E to correspond with items listed on the classroom whiteboard. In some cases, it may be helpful to create slides on-the-fly to ask students if they recommend "more" or "less" of something, such as small group discussion or readings. |

| Group-Work Evaluations | 349 | Use clickers to collect answers to the fixed-response questions and develop additional fixed-response questions as needed. To identify specific groups that might require intervention, polling cannot be anonymous to the instructor, but it can still be anonymous to students. With some systems, responses can be directed to the course's online test center or grade book and analyzed by group. |

| Assessing Learner Reactions to Class Activities, Assignments,andMaterials | ||

| Reading Rating Sheets | 352 | |

| Assignment Assessments | 356 | |

| Exam Evaluations | 358 | |

|

Total |

23 (of 50) | |

| Used As-Is/Adapted to Clickers | 13/10 |

* If the cell is empty, no adaptation to the original instructions is needed to conduct the CAT with clickers.