- Writing effectively is academically and professionally crucial for students, and helping them attain that skill is a major goal for writing instruction.

- The social networking site Ning offers a variety of Web 2.0 tools that can help students learn to write as well as write to learn.

- A small pilot in a University of Connecticut writing course demonstrated Ning’s effectiveness in helping students write to learn.

Since the 1960s, the “write to learn†approach has become increasingly prevalent in American schools. This approach gained supporters after James Britton et al.’s influential study, The Development of Writing Abilities,1 which examines different types of writing and their respective purposes. The expressive, defined as informal or quotidian language, is the principal means by which we understand new experiences and concepts; it is also the foundation for subsequent forms of written expression that are more formalized and analytical. According to Britton et al., the expressive facilitates learning, as it allows students to assimilate new knowledge and perspectives. In another important article, “Writing as a Method of Learning,†Janet Emig explains how writing combines the three important elements of learning as discussed by both Jerome Bruner and Jean Piaget (enactive — learn by doing; iconic — learn by depiction in an image; and representational or symbolic — learn by restating in words).2 Based on these and other studies, educators now often view writing not only as a means of evaluating what students “know†but also as a powerful tool that fosters learning, the ability to understand new material, and the ability to think critically.

In our personal experience teaching a 200-level writing course at the University of Connecticut, we also discovered first-hand how the write-to-learn approach helps students understand concepts and formulate their own ideas. Despite their advantages, we felt that traditional write-to-learn activities lacked a key element that would benefit our modern learners: technology. Before the predominance of computers, write-to-learn activities usually consisted of informal writing journals that may or may not be shared with other students. Why not combine the traditional elements of a write-to-learn activity with the exciting possibilities available through technology, such as the addition of images, video, and global interaction?

This article describes our personal experiment using Ning, a social networking site, to implement a semester-long write-to-learn activity with two sections of the writing course French Literature and Civilization in Translation. Although what follows is a personal account rather than an exhaustive scientific study, we hope that a discussion of our experience, our students’ feedback, and perceived results will guide others considering such activities in their classrooms.

Course Objectives and Details

The French Literature and Civilization in Translation class fulfills a general education requirement at the University of Connecticut. Open to the entire university, the course attracts students from all disciplines, which is one of its distinguishing features. In hopes of exposing students to different cultural and historical aspects of several Francophone regions, we ask students to read French and/or Francophone works of literature in their translated form as well as to analyze topics relevant to these works via written assignments.

As educators, we strongly believe in the importance of learning to write and writing to learn, as does the University of Connecticut Writing Center. Designated a “W†course by the Writing Center, French Literature and Civilization in Translation emphasizes student writing, of which 15 pages must be analytical writing. In such papers we expect to see an introduction with a thesis statement followed by a structured body and ending with a strong conclusion. However, in the spring of 2009 we also chose to expose our students to other styles of writing, which is one reason we decided to introduce the Ning activity into the course. Before the spring semester began, we created one Ning page on which both sections of the French Literature and Civilization in Translation class would participate.

On Ning postings completed outside of class, students wrote in first person, expressed opinions, and critiqued each other rather than analyzing the work of literature or film we were discussing in class at the time. This style of writing calls for cohesive, convincing, succinct expression of ideas in a short paragraph. These paragraphs were never considered part of the 15 analytic pages required by the University of Connecticut’s course description; however, we felt that this write-to-learn activity could not only help students formulate ideas, but it could help improve their writing skills for both analytic and creative paper assignments in the class.

In addition to the four academic papers required in the class, we also asked students to write their own short story following the unit on short stories and films. In combination with the analytic, creative, and “free writing†that students did on Ning, we also held in-class writing workshops on specific grammatical (such as use of punctuation), stylistic (such as making prose less conversational), and structural (such as outlining a paper) issues. While students wrote frequently on the Ning site, their work there was merely one component of their overall grade and not our only means of evaluating the progress in their writing.

Ning

We chose to use Ning as a means to achieve the course writing objectives based not only on what the site has to offer but also on what other tools that we had previously used did not offer. Ning is a social networking site created by Gina Bianchini and Marc Andreessen. The first networks appeared in February 2007, and today Ning has approximately 1.6 million networks and 36 million registered users.4 Although it shares some features with other social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace, Ning sets itself apart by focusing on groups and common interests rather than individuals’ personal pages. We felt that Ning had several benefits not available in a blog, on Blackboard, or through sites like Facebook.

Social Networking

Social networking sites like Facebook and MySpace dominate the social landscape on American university and college campuses. As pointed out in the EDUCAUSE “7 Things You Should Know About Facebook†brief:

Any technology that is able to captivate so many students for so much time not only carries implications for how those students view the world but also offers an opportunity for educators to understand the elements of social networking that students find so compelling and to incorporate those elements into teaching and learning.5

Ning offers many of the same features present on other, more popular social networking sites, such as personal profile pages, chat capabilities, and the ability to connect with other members. As instructors, we personally chose to avoid Facebook and MySpace because we feared students might view our presence there as an invasion of their “personal†space. Despite its popularity, Ning is still much less commonly used by college students, thus making it neutral territory for our experiment.

Sense of Student Ownership/Accountability

Traditional write-to-learn activities already attempt to create a student-centered environment, but we felt that Ning would encourage an even greater sense of responsibility, ownership, and accountability in our students. We expected this sense of ownership and accountability to increase and become more important over time because instead of being private (like some traditional writing journals) or only shared with other members of the class (as is the case with most Blackboard forums), student contributions would be visible to a global community through the Ning network, since we chose very open privacy settings. Ning network creators can make their sites as public or private as they wish. Students knew that their work was being followed by outside members thanks to certain web gadgets or “widgets†(neocounter, clustrmaps, and hit counters; see Figure 1) that we added to the site. With a public forum, students would be required to stand behind their work, encouraging them to take the activity seriously and put forth their best efforts.

Figure 1. Our Hit Counter, Clustrmap, and Neocounter Widgets

Multimedia Capabilities

Ning allows students to be more creative than traditional write-to-learn activities and some other Web 2.0 technologies because of the multimedia capabilities. Students can include video, images, music, and links in their forum posts and profile pages. We felt that this would allow our students, who commonly use web-based sources for personal and academic research, to better express themselves and explore the topics discussed in the course. Also, the ability to include widgets was a fun way for students to see who was watching their progress, which is not an option with traditional writing activities or Blackboard.

Global Perspectives

The inclusion of global perspectives was essential to this project, not only because of the ever-increasing (electronically) connected nature of our world but also because the course itself dealt with literature and cinema from several different countries. Using Ning allowed us to reach an international community that shared an interest in French or Francophone cinema and literature. This, we hoped, would embolden discussion and allow for optimal academic growth.

Archive of Student Work

Ning offers a way to archive student work, safeguarding contributions to the site even after the semester has finished. This feature allows instructors to access past work without having to make an official request to their university technology department (which is often the case with Blackboard). It also allows students to revisit their work for personal, academic, or professional reasons.

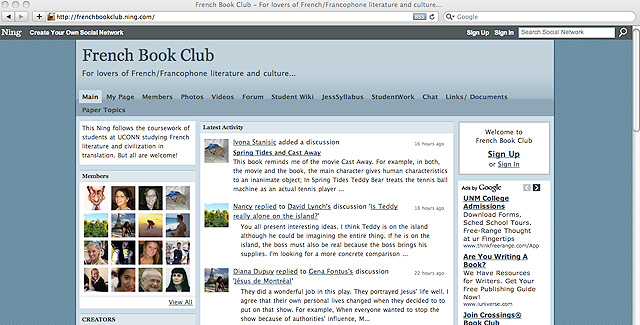

Figure 2 shows the Ning home page for the French Book Club. This Ning gathered the students’ coursework from both sections as they explored different discussion topics. This snapshot was taken on November 27, 2009, although it changes daily since the Ning site is still in use with the current sections of French Literature and Civilization in Translation courses.

Figure 2. Ning French Book Club Home Page

Student Experience

At the beginning of the semester, we thoroughly explained to our students that their work on the Ning would be completely open to the public and that we had assigned a Creative Commons license to the site. Our license meant that we invited outsiders to use information from our site but that they needed to use proper attribution. To ensure privacy, we emphasized to students that they did not have to post a real picture of themselves or write their names on their profile pages; instead they could use an alias if they felt more comfortable with that. However, none of them did so, and we believe this happened as a result of their daily activities on other social networking sites such as Facebook, where they often allow anyone to view their personal pages. Many students enjoyed uploading various multimedia elements such as music, pictures, and YouTube clips, as well as trying to make their profile pages more esthetically pleasing by changing the theme. Besides finding the social and creative elements of Ning to be “fun,†our students seemed to truly enjoy the writing experience on the site. As one student noted:

“I found Ning to be something very different than I have used before in a class. Here at UCONN, we have the discussion boards on HuskyCT, but with Ning we were able to add people from all over who shared an interest in French Literature. Also, we were able to decorate our personal pages with our specific interests. I would say seeing what other people wrote in their posts helped my writing. I could also see a different perspective on the topic which helped me by knowing what other writing styles students were using.â€

At the end of the semester, we asked our respective classes to evaluate the use of Ning by filling out questionnaires anonymously. The survey posed both open-ended and “yes or no†questions. Student response to the Ning page varied, both within classes and between the two sections, but overall students indicated that they had a positive experience with the site. In terms of the perceived benefits, the student responses from both classes were identical. When asked in the open-ended section of the survey what they felt were the top three benefits of the Ning, both classes agreed:

- Ning gave them the opportunity to hear other opinions on the material covered in class.

- It helped them prepare for class discussions.

- It sparked new ideas for paper topics.

All three of these benefits were important to our conceived write-to-learn activity.

Responses to what could improve the experience varied between the two sections. Students from both sections felt that the most improvement could be made to some of the technical aspects of the site, such as the addition of a spell-check feature, the need for the ability to edit after making a post, and so forth. Unfortunately, all of these areas of improvement are largely out of our hands. Students also expressed the desire for more collaboration between the two sections who shared the Ning site, but occasionally discussed different materials.

In the “yes or no†section of the evaluation, both classes also agreed that the two most successful elements of the Ning were:

- Its ability to help students prepare for class

- Their perception that their writing improved over the course of the semester

Preparing Students for Class

In both sections, our students enjoyed reading each other’s comments, responses, and questions on the shared Ning page. Once a student posted a question and others started responding, their posts turned into an online dialogue in which new ideas, perspectives, interpretations, and opinions were discussed and developed. Moreover, the online conversations spilled over into classroom time because students regularly initiated class discussion with their thoughts about the postings. In essence, their work on Ning fueled the level of participation inside the classroom, creating a link between the online written work and oral discussion. Having the opportunity to read their fellow students’ opinions led them to feel more prepared for class, and in effect class time became an extension of the online work, with both elements simultaneously nurturing each other.

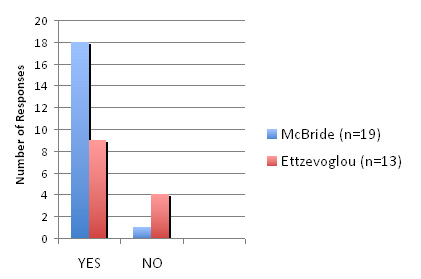

Figure 3 illustrates student responses to the survey question about preparing for class (n = number of students). See also “Student Responses†for open-ended student feedback to the survey question.

Figure 3. Responses to Question 6: Ning Helped Students Prepare for Class

Improving Student Writing

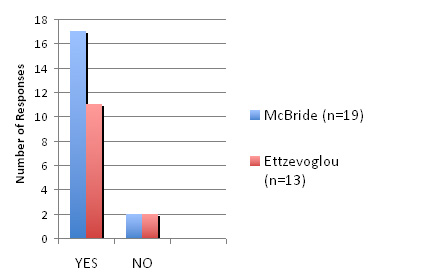

The overwhelming majority of students from both sections who responded to the survey (28 of 32 total) said that posting on Ning helped their writing. As instructors, we were extremely happy with this perceived improvement.

As mentioned earlier, we assigned many forms of writing throughout the semester. The writing assignments on Ning challenged our students to write strong, succinct, and polished opinions based on the literature. This style of writing is completely different from our expectations of the longer analytical papers we assigned. Even though we took a hands-off approach to instructor participation on the page, our survey results show that students appreciated the chance to learn from each other, which helped them learn to develop ideas — an important element of any write-to-learn activity. Instead of periodic peer-editing sessions, our students were exposed to each other’s styles of writing on a daily basis and could always refer back to any posting. Moreover, even though outside members did not participate as much as we had hoped, the students felt that the experience with Ning was worthwhile and an innovative way to elicit writing samples without daily writing activities in the classroom.

Figure 4 illustrates student responses to the survey question about improved writing (n = number of students). See also “Student Responses†for open-ended student feedback to the survey question.

Figure 4. Responses to Question 7: Ning Helped Students Improve Their Writing

Instructor Experience

Based on our prior experience with both traditional and web-based write-to-learn activities, we felt that Ning best met our needs as determined by the course and activity objectives. This does not mean, however, that our experience was without difficulty. Here we reexamine the five perceived benefits of Ning and discuss how well it did or did not stack up.

Social Networking

The social networking aspect of Ning succeeded in encouraging students to visit the site, even if just to add pictures or “friend†a new member. As instructors, we felt that this element of the tool helped create a sense of community and encouraged what Barbara Ganley and Barbara Sawhill term social learning, “the forming of close bonds with the learning community itself and with the outside world.â€6

Sense of Student Ownership/Accountability

We felt, as did our students, that the course Ning site ended up being largely their own creation. For the most part they indicated that the lack of instructor interaction was beneficial. Despite a few instances when both students and instructors sensed that some sort of contribution from the instructor could have improved the quality of forum discussions, the students were ultimately more comfortable and in control as a result of the “silent observer†role that we assumed as instructors. In order to make sure students were aware of our presence even if we did not actively contribute, and in order to give important feedback on their ideas and writing, we provided frequent informal (detailed, but not graded) evaluations.

Multimedia Capabilities

Although including different media is much easier on Ning than on Blackboard or traditional writing assignments, we took advantage of Ning’s multimedia capabilities far more often than did the students. Students frequently uploaded personal pictures, favorite music, or interesting videos to their profile pages, but they did not take advantage of their ability to upload media to their forum discussion posts. In the future, when introducing Ning we plan to focus more on how exciting these features can be and encourage students to seek out pertinent videos, images, and links to include in their forum discussion posts.

Global Perspectives

Both the students and we have been impressed with the amount of exposure our site has received. Students indicated a sense of pride and importance from the fact that people from all over the world came to see what they wrote (see Figure 5). However, participation from outside members was less frequent than we had hoped. We still believe that contributions from outside members will increase student engagement and formulation of ideas, since it has been our experience that the most lively classroom discussions came after an outside member commented in the forum. In class and in the forum, students stood behind their ideas, reinforcing the importance of accountability.

Figure 5. Magnified Clustrmap of Outside Members’ Locations

Archive of Student Work

Archiving of work is probably the hardest for us to evaluate, since determining its success lies more in the hands of former students. When we asked students if they would continue to use Ning after the class ended, one student communicated the general reaction:

“It's a little debatable whether or not I will continue using and checking Ning after the semester ends just because of its nature. I'm interested in French Literature, but if I am not currently reading any of the same books or am not involved with French Literature, I'm not sure if I would find it helpful, and therefore would not be able to contribute so much, and would essentially stop using it. However as I come across different pieces of information, such as the Gawker link I posted today, or things about French Literature I may come across on other websites, or even music that pertains to one of the overarching themes we've covered in the semester, I'll probably go back to the Ning website and utilize it accordingly.â€

In the future, we hope to ask former students to inform us when using the Ning page as an archival example of their work; however, this might become increasingly difficult as they graduate and possibly leave the area. (See “Student Responses.â€) As instructors, we appreciate being able to:

- Reference past discussions

- Archive exceptional student work in a special section

- Keep in touch with former students through the Ning site

None of this was possible for us using either traditional written activities or Blackboard.

Conclusion

We have continued to implement and improve the write-to-learn Ning page project with subsequent class sections. Although using Ning in our courses remains a work in progress, we believe that this tool has effectively helped our students see the benefits of writing to learn in a way that would not have been possible with traditional activities or other web-based tools. Ning provides an environment in which our students can learn how to express themselves in writing and how to share their thoughts with others from all over the world. This approach upholds the University of Connecticut General Education Guidelines, which mandate that students should not write simply to be evaluated; they should learn how writing can “ground, extend, deepen, and even enable their learning of course material.â€7 We hope that after using the write-to-learn approach in combination with the Ning social networking site, students will continue both the personal and the academic growth that they began in this class.

- James Britton et al. The Development of Writing Abilities (London: MacMillan, 1975).

- Janet Emig, “Writing as a Mode of Learning,†College Composition and Communication, vol. 28, no. 2 (May 1977), pp. 122–128.

- Anne Ruggles Gere, ed., Roots in the Sawdust: Writing to Learn across the Disciplines (Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1985).

- “About Ning.â€

- “7 Things You Should Know About Facebook,†EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, September 2006.

- Barbara Ganley and Barbara Sawhill, “How Did a Couple of Veteran Classroom Teachers End Up in a Space Like This? Extraordinary Intersections Between Learning, Social Software and Teaching,†The Knowledge Tree, edition 15 (2007).

- From the UConn Writing Center definition of W courses, which integrate the General Education Guidelines.

© 2009 Nathalie Ettzevoglou and Jessica McBride. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.